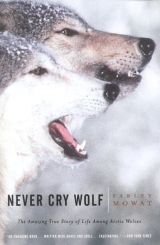

Текст книги "Never Cry Wolf"

Автор книги: Farley Mowat

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 6 (всего у книги 10 страниц)

The next time we encountered Mike I recalled him to his promise and he began to interrogate Ootek.

“Yesterday,” he told me, “Ootek says that wolf you call George, he send a message to his wife. Ootek hear it good. He tell his wife the hunting is pretty bad and he going to stay out longer. Maybe not get home until the middle of the day.”

I remembered that Ootek could not have known at what time the male wolves returned home, for he was then fast asleep inside the tent. And 12:17 is close enough to the middle of the day for any practical purpose.

Nevertheless, for two more days my skepticism ruled—until the afternoon when once again George appeared on the crest and cocked his ears toward the north. Whatever he heard, if he heard anything, did not seem to interest him much this time, for he did not howl, but went off to the den to sniff noses with Angeline.

Ootek, on the other hand, was definitely interested. Excitement filled his face. He fairly gabbled at me, but I caught only a few words. Innuit (eskimos) and kiyai (come) were repeated several times, as he tried passionately to make me understand. When I still looked dense he gave me an exasperated glance and, without so much as a by-your-leave, headed off across the tundra in a direction which would have taken him to the northwest of Mike’s cabin.

I was a little annoyed by his cavalier departure, but I soon forgot about it, for it was now late afternoon and all the wolves were becoming restless as the time approached for the males to set off on the evening hunt.

There was a definite ritual about these preparations. George usually began them by making a visit to the den. If Angeline and the pups were inside, his visit brought them out. If they were already outside, Angeline’s behavior changed from that of domestic boredom to one of excitement. She would begin to romp; leaping in front of George, charging him with her shoulder, and embracing him with her forelegs. George seemed at his most amiable during these playful moments, and would sometimes respond by engaging in a mock battle with his mate. From where I sat these battles looked rather ferocious, but the steadily wagging tails of both wolves showed it was all well meant.

No doubt alerted by the sounds of play, Uncle Albert would appear on the scene and join the group. He often chose to sleep away the daylight hours some distance from the den site, perhaps in order to reduce the possibility of being dragooned into the role of babysitter at too frequent intervals.

With his arrival, all three adult wolves would stand in a circle, sniff noses, wag their tails hard, and make noises. “Make noises” is not very descriptive, but it is the best I can do. I was too far off to hear more than the louder sounds, and these appeared to be more like grunts than anything else. Their meaning was obscure to me, but they were certainly connected with a general feeling of good will, anticipation and high spirits.

After anywhere from twenty minutes to an hour of conviviality (in which the pups took part, getting under everyone’s feet and nipping promiscuously at any adult tail they might encounter) the three adults would adjourn to the crest of the den, usually led by Angeline. Once more they would form a circle and then, lifting their heads high, would “sing” for a few minutes.

This was one of the high points of their day, and it was certainly the high point of mine. The first few times the three wolves sang, the old ingrained fear set my back hairs tingling, and I cannot claim to having really enjoyed the chorus. However, with the passage of sufficient time I not only came to enjoy it, but to anticipate it with acute pleasure. And yet I find it almost impossible to describe, for the only terms at my disposal are those relating to human music and these are inadequate if not actually misleading. The best I can do is to say that this full-throated and great-hearted chorus moved me as I have very occasionally been moved by the bowel-shaking throb and thunder of a superb organ played by a man who had transcended his mere manhood.

The impassionata never lasted long enough for me. In three or four minutes it would come to an end and the circle would break up; once more with much tail wagging, nose sniffing and general evidence of good will and high content. Then, reluctantly, Angeline would move toward the den, often looking back to watch as George and Albert trotted off along one of the hunting trails. She made it clear that she wished desperately to join them; but in the end she would rejoin the pups instead, and once more submit to their ebullient demands, either for dinner or for play.

On this particular night the male wolves made a break from their usual routine. Instead of taking one of the trails leading north, or northwest, they headed off toward the east, in the opposite direction from Mike’s cabin and me.

I thought no more about this variation until sometime later when a human shout made me turn around. Ootek had returned—but he was not alone. With him were three bashful friends, all grinning, and all shy at this first meeting with the strange kablunak who was interested in wolves.

The arrival of such a mob made further observations that night likely to be unproductive, so I joined the four Eskimos in the trek to the cabin. Mike was home, and greeted the new visitors as old friends. Eventually I found a chance to ask him a few questions.

Yes, he told me, Ootek had indeed known that these men were on their way, and would soon arrive.

How did he know?

A foolish question. He knew because he had heard the wolf on the Five Mile Hills reporting the passage of the Eskimos through his territory. He had tried to tell me about it; but then, when I failed to understand, he had felt obliged to leave me in order to intercept and greet his friends.

And that was that.

14

Puppy Time

DURING THE third week in June, Angeline began to show increasing signs of restlessness. She gave the distinct impression that her too domestic life at the den was beginning to pall. When George and Albert departed of an evening for the hunt, she took to accompanying them on the first part of their journey. At first she went no further than a hundred yards from the den; but on one occasion she covered a quarter of a mile before returning slowly home.

George was clearly delighted with her changing mood. He had been trying for weeks to persuade her to join him on the night-long ranging across the tundra. On one occasion he had delayed his departure by a good hour—long after Albert had grown impatient and struck off on his own—in an attempt to entice his mate into going along.

During that hour he made eight trips from the lookout ridge down to the nursery knoll where Angeline was lying in the midst of her pups. Each time he sniffed her fondly, wagged his tail furiously and then started hopefully off toward the hunting trail. And each time, when she failed to follow, he returned to the lookout knoll to sit disconsolately for a few minutes before trying again. When he finally did depart, alone, he was the picture of disappointment and dejection, with head and tail both held so low that he seemed to slink away.

The desire to have a night out together was clearly mutual, but the welfare of the pups remained paramount with Angeline, even though they seemed large enough and able enough to need far less attention.

On the evening of June 23 I was alone at the tent—Ootek having gone off on some business of his own for a few days—when the wolves gathered for their pre-hunt ritual singsong. Angeline surpassed herself on this occasion, lifting her voice in such an untrammeled paean of longing that I wished there were some way I could volunteer to look after the kids while she went off with George. I need not have bothered. Uncle Albert also got the message, or perhaps he had received more direct communications, for when the song was done Angeline and George trotted buoyantly off together, while Albert mooched morosely down to the den and settled himself in for an all-night siege of pups.

A few hours later a driving rain began and I had to give up my observations.

There were no wolves in sight the next morning when the rain ceased, the mist lifted, and I could again begin observing; but shortly before nine o’clock George and Uncle Albert appeared on the crest of the esker.

Both seemed nervous, or at least uneasy. After a good deal of restless pacing, nose sniffing, and short periods of immobility during which they stared intently over the surrounding landscape, they split up. George took himself off to the highest point of the esker, where he sat down in full view and began to scan the country to the east and south. Uncle Albert trotted off along the ridge to the north, and lay down on a rocky knoll, staring out over the western plains.

There was still no sign of Angeline, and this, together with the unusual actions of the male wolves, began to make me uneasy too. The thought that something might have happened to Angeline struck me with surprising pain. I had not realized how fond I was becoming of her, but now that she appeared to be missing I began to worry about her in dead earnest.

I was on the point of leaving my tent and climbing the ridge to have a look for her myself, when she forestalled me. As I took a last quick glance through the telescope I saw her emerge from the den—with something in her mouth—and start briskly across the face of the esker. For a moment I could not make out what it was she was carrying, then with a start of surprise I recognized it as one of the pups.

Making good time despite her burden—the pup must have weighed ten or fifteen pounds—she trotted diagonally up the esker slope and disappeared into a small stand of spruce. Fifteen minutes later she was back at the den for another pup, and by ten o’clock she had moved the last of them.

After she disappeared for the final time both male wolves gave up their vigils—they had evidently been keeping guard over the move—and followed her; leaving me to stare bleakly over an empty landscape. I was greatly perturbed. The only explanation which I could think of for this mass exodus was that I had somehow disturbed the wolves so seriously they had felt impelled to abandon their den. If this was indeed the case, I knew I would only make matters worse by trying to follow them. Not being able to think of anything else to do, I hurried back to the cabin to consult Ootek.

The Eskimo immediately set my fears at rest. He explained that this shifting of the pups was a normal occurrence with every wolf family at about this time of year. There were several reasons for it, so he told me. In the first place the pups had now been weaned, and, since there was no water supply near the den, it was necessary to move them to a location where they could slack their thirst elsewhere than at their mother’s teats. Secondly, the pups were growing too big for the den, which now could barely contain them all. Thirdly, and perhaps most important, it was time for the youngsters to give up baby-hood and begin their education.

“They are too old to live in a hole in the ground, but still too young to follow their parents,” Mike interpreted, as Ootek explained. “So the old wolves take them to a new place where there is room for the pups to move around and to learn about the world, but where they are still safe.”

As it happened both Ootek and Mike were familiar with the location of the new “summer den,” and the next day we moved the observation tent to a position partly overlooking it.

The pups’ new home, half a mile from the old den, was a narrow, truncated ravine filled with gigantic boulders which had been split off the cliff walls by frost action. A small stream ran through it. It also embraced an area of grassy marsh which was alive with meadow mice: an ideal place for the pups to learn the first principles of hunting. Exit to and entry from the ravine involved a stiff climb, which was too much for the youngsters, so that they could be left in their new home with little danger of their straying; and since they were now big enough to hold their own with the only other local carnivores of any stature—the foxes and hawks—they had nothing to fear.

I decided to allow the wolves time to settle in at the summer den before resuming my close watch upon them, and so I spent the next night at the cabin catching up on my notes.

That evening Ootek added several new items to my fund of information. Among other interesting things he told me that wolves were longer-lived than dogs. He had personally known several wolves who were at least sixteen years old, while one wolf patriarch who lived near the Kazan River, and who had been well known to Ootek’s father, must have been over twenty years old before he disappeared.

He also told me that wolves have the same general outlook toward pups that Eskimos have toward children—which is to say that actual paternity does not count for much, and there are no orphans as we use the term.

Some years earlier a wolf bitch who was raising her family only a mile or two from the camp where Ootek was then living was shot and killed by a white man who was passing through the country by canoe. Ootek, who considered himself to be magically related to all wolves, was very upset by the incident. There was a Husky bitch with pups in the Eskimo camp at the time, and so he determined to dig out the wolf pups and put them with the bitch. However, his father deterred him by telling him it would not be necessary—that the wolves would solve the problem in their own way.

Although his father was a great shaman, and could be relied upon to speak the truth, Ootek was not wholly convinced and so he took up his own vigil over the den. He had not been in hiding many hours, so he told me, when he saw a strange wolf appear in company with the widowed male, and both wolves entered the den. When they came out, each was carrying a pup.

Ootek followed them for several miles until he realized they were heading for a second wolf den, the location of which was also known to him. By running hard, and by taking short cuts, he reached this second den before the two wolves did, and was present when they arrived.

As soon as they appeared the female who owned the den, and who had a litter of her own, came to the den mouth, seized the two pups one after another by the scruff of their necks and took them into the den. The two males then departed to fetch another pair of pups.

When the move was completed there were ten pups at this second den, all much of a size and age and, as far as Ootek could tell, all treated with identical care and kindness by the several adults, now including the bereaved male.

This was a touching story, but I am afraid I did not give it due credence until some years later when I heard of an almost identical case of adoption of motherless wolf pups. On this occasion my informant was a white naturalist of such repute that I could hardly doubt his word—though, come to think of it, I am hard put to explain just why his word should have any more weight than Ootek’s, who was, after all, spiritually almost a wolf himself.

I took this opportunity to ask Ootek if he had ever heard of the time-honored belief that wolves sometime adopt human children. He smiled at what he evidently took to be my sense of humor, and the gist of his reply was that this was a pretty idea, but it went beyond the bounds of credibility. I was somewhat taken aback by his rather condescending refusal to accept the wolf-boy as a reality, but I was really shaken when he explained further.

A human baby put in a wolf den would die, he said, not because the wolves wished it to die, but simply because it would be incapable, by virtue of its inherent helplessness, of living as a wolf. On the other hand it was perfectly possible for a woman to nurse a pup to healthy adulthood, and this sometimes happened in Eskimo camps when a husky bitch died. Furthermore, he knew of at least two occasions where a woman who had lost her own child and was heavy with milk had nursed a wolf pup—Husky pups not being available at the time.

15

Uncle Albert Falls in Love

THE NEW location of the summer den was ideal from the wolves’ point of view, but not from mine, for the clutter of boulders made it difficult to see what was happening. In addition, caribou were now trickling back into the country from the north, and the pleasures of the hunt were siren calls to all three adult wolves. They still spent most of each day at or near the summer den, but they were usually so tired from their nightly excursions that they did little but sleep.

I was beginning to find time hanging heavy on my hands when Uncle Albert rescued me from boredom by falling in love.

When Mike departed from the cabin shortly after my first arrival there he had taken all his dogs with him—not, as I suspected, because he did not trust them in the vicinity of my array of scalpels, but because the absence of caribou made it impossible to feed them. Throughout June his team had remained with the Eskimos, whose camps were in the caribous’ summer territory; but now that the deer were returning south the Eskimo who had been keeping the dogs brought them back.

Mike’s dogs were of aboriginal stock, and were magnificent beasts. Contrary to yet another myth, Eskimo dogs are not semi-domesticated wolves—though both species may well have sprung from the same ancestry. Smaller in stature than wolves, true Huskies are of a much heavier build, with broad chests, shorter necks, and bushy tails which curl over their rumps like plumes. They differ from wolves in other ways too. Unlike their wild relations, Husky bitches come into heat at any time of the year with a gay disregard for seasons.

When Mike’s team returned to the cabin one of the bitches was just coming into heat. Being hot-blooded by nature, and amorous by inclination, this particular bitch soon had the rest of the team in an uproar and was causing Mike no end of trouble. He was complaining about the problem one evening when inspiration came to me.

Because of their continent habits, my study of the wolves had so far revealed nothing about their sexual life and, unless I was prepared to follow them about during the brief mating season in March, when they would be wandering with the caribou herds, I stood no chance of filling in this vital gap in my knowledge.

Now I knew, from what Mike and Ootek had already told me, that wolves are not against miscegenation. In fact they will mate with dogs, or vice versa, whenever the opportunity arises. It does not arise often, because the dogs are almost invariably tied up except when working, but it does happen.

I put my proposition to Mike and to my delight he agreed. In fact he seemed quite pleased, for it appeared that he had long wished to discover for himself what kind of sled dogs a wolf-husky cross would make.

The next problem was how to arrange the experiment so that my researches would benefit to the maximum degree. I decided to do the thing in stages. The first stage was to consist of taking the bitch, whose name was Kooa, for a walk around the vicinity of my new observation site, in order to make her existence and condition known to the wolves.

Kooa was more than willing. In fact, when we crossed one of the wolf trails she became so enthusiastic it was all I could do to restrain her impetuosity by means of a heavy chain leash. Dragging me behind her she plunged down the trail, sniffing every marker with uninhibited anticipation.

It was with great difficulty that I dragged her back to the cabin where, once she was firmly tethered, she reacted by howling her frustration the whole night through.

Or perhaps it was not frustration that made her sing; for when I got up next morning Ootek informed me we had had a visitor. Sure enough, the tracks of a big wolf were plainly visible in the wet sand of the riverbank not a hundred yards from the dog-lines. Probably it was only the presence of the jealous male Huskies which had prevented the romance from being consummated that very night.

I had been unprepared for such quick results, although I should have foreseen that either George or Albert would have been sure to find some of Kooa’s seductively scented billets-doux that same evening.

I now had to rush the second phase of my plan into execution. Ootek and I repaired to the observation tent and, a hundred yards beyond it in the direction of the summer den, we strung a length of heavy wire between two rocks about fifty feet from one another.

The next morning we led Kooa (or more properly, were led by Kooa) to the site. Despite her determined attempts to go off wolf seeking on her own, we managed to shackle her chain to the wire. She retained considerable freedom of movement with this arrangement, and we could command her position from the tent with rifle fire in case anything went wrong.

Rather to my surprise she settled down at once and spent most of the afternoon sleeping. No adult wolves were in evidence near the summer den, but we caught glimpses of the pups occasionally as they lumbered about the little grassy patch, leaping and pouncing after mice.

About 8:30 P.M. the wolves suddenly broke into their pre-hunting song, although they themselves remained invisible behind a rock ridge to the south of the den.

The first sounds had barely reached me when Kooa leaped to her feet and joined the chorus. And how she howled! Although there is not, as far as I am aware, any canine or lupine blood in my veins, the seductive quality of Kooa’s siren song was enough to set me thinking longingly of other days and other joys.

That the wolves understood the burden of her plaint was not long in doubt. Their song stopped in mid-swing, and seconds later all three of them came surging over the crest of the ridge into our view. Although she was a quarter of a mile away, Kooa was clearly visible to them. After only a moment’s hesitation, both George and Uncle Albert started toward her at a gallop.

George did not get very far. Before he had gone fifty yards Angeline had overtaken him and, while I am not prepared to swear to this, I had the distinct impression that she somehow tripped him. At any rate he went sprawling in the muskeg, and when he picked himself up his interest in Kooa seemed to have evaporated. To do him justice, I do not believe he was interested in her in a sexual way—probably he was simply taking the lead in investigating a strange intruder into his domain. In any event, he and Angeline withdrew to the summer den, where they lay down together on the lip of the ravine and watched proceedings, leaving it up to Uncle Albert to handle the situation as he saw fit.

I do not know how long Albert had been celibate, but it had clearly been too long. When he reached the area where Kooa was tethered he was moving so fast he overshot. For one tense moment I thought he had decided we were competing suitors and was going to continue straight on into the tent to deal with us; but he got turned somehow, and his wild rush slowed. Then when he was within ten feet of Kooa, who was awaiting his arrival in a state of ecstatic anticipation, Albert’s manner suddenly changed. He stopped dead in his tracks, lowered his great head, and turned into a buffoon.

It was an embarrassing spectacle. Laying his ears back until they were flush with his broad skull, he began to wiggle like a pup while at the same time wrinkling his lips in a frightful grimace which may have been intended to register infatuation, but which looked to me more like a symptom of senile decay. He also began to whine in a wheedling falsetto which would have sounded disgusting coming from a Pekinese.

Kooa seemed nonplussed by his remarkable behavior. Obviously she had never before been wooed in this surprising manner, and she seemed uncertain what to do about it. With a half-snarl she backed away from Albert as far as her chain would permit.

This sent Albert into a frenzy of abasement. Belly to earth, he began to grovel toward her while his grimace widened into an expression of sheer idiocy.

I now began to share Kooa’s concern, and thinking the wolf had taken complete leave of his senses I was about to seize the rifle and go to Kooa’s rescue, when Ootek restrained me. He was grinning; a frankly salacious grin, and he was able to make it clear that I was not to worry; that things were progressing perfectly normally from a wolfish point of view.

At this point Albert shifted gears with bewildering rapidity. Scrambling to his feet he suddenly became the lordly male. His ruff expanded until it made a huge silvery aura framing his face. His body stiffened until he seemed to be made of white steel. His tail rose until it was as high, and almost as tightly curled, as a true Husky’s. Then, pace by delicate pace, he closed the gap.

Kooa was no longer in doubt. This was something she could understand. Rather coyly she turned her back toward him and as he stretched out his great nose to offer his first caress she spun about and nipped him coyly on the shoulder….

My notes on the rest of this incident are fully detailed but I fear they are too technical and full of scientific terminology to deserve a place in this book. I shall therefore content myself by summing up what followed with the observation that Albert certainly knew how to make love.

My scientific curiosity had been assuaged, but Uncle Albert’s passion hadn’t, and a most difficult situation now developed. Although we waited with as much patience as we could muster for two full hours, Albert showed not the slightest indication of ever intending to depart from his new-found love. Ootek and I wished to return to the cabin with Kooa, and we could not wait forever. In some desperation we finally made a sally toward the enamored pair.

Albert stood his ground, or rather he ignored us totally. Even Ootek seemed somewhat uncertain how to proceed after we reached a point not fifteen feet from the lovers without Albert’s having given any sign that he might be inclined to leave. It was a stalemate which was only broken when I, with much reluctance, fired a shot into the ground a little way from where Albert stood.

The shot woke him from his trance. He leaped high into the air and bounded off a dozen yards, but having quickly recovered his equanimity he started to edge back toward us. Meanwhile we had untied the chain, and while Ootek dragged the sullenly reluctant Kooa off toward home, I covered the rear with the rifle.

Albert stayed right with us. He kept fifteen to twenty yards away, sometimes behind, sometimes on the flanks, sometimes in front; but leave us he would not.

Back at the cabin we again tried to cool his ardor by firing a volley in the air, but this had no effect except to make him withdraw a few yards farther off. There was obviously nothing for it but to take Kooa into the cabin for the night; for to have chained her on the dog-line with her teammates would have resulted in a battle royal between them and Albert.

It was a frightful night. The moment the door closed, Albert broke into a lament. He wailed and whooped and yammered without pause for hours. The dogs responded with a cacophony of shrill insults and counterwails. Kooa joined in by screaming messages of undying love. It was an intolerable situation. By morning Mike was threatening to do some more shooting, and in real earnest.

It was Ootek who saved the day, and possibly Albert’s life as well. He convinced Mike that if he released Kooa, all would be well. She-would not run away, he explained, but would stay in the vicinity of the camp with the wolf. When her period of heat was over she would return home and the wolf would go back to his own kind.

He was perfectly right, as usual. During the next week we sometimes caught glimpses of the lovers walking shoulder to shoulder across some distant ridge. They never went near the den esker, nor did they come close to the cabin. They lived in a world all their own, oblivious to everything except each other.

They were not aware of us, but I was uncomfortably aware of them, and I was glad when, one morning, we found Kooa lying at her old place in the dog-line looking exhausted but satiated.

The next evening Uncle Albert once more joined in the evening ritual chorus at the wolf esker. However, there was now a mellow, self-satisfied quality to his voice that I had never heard before, and it set my teeth on edge. Braggadocio is an emotion which I have never been able to tolerate—not even in wolves.

16

Morning Meat Delivery

SINCE THE removal of the pups to the ravine they had been largely hidden from my view; and so one morning, before Angeline or the two males had returned from the nightly hunt, I made my way to an outcropping of rocks crowned with a scrub of dwarfed spruces which overlooked the ravine from a distance of less than a hundred feet. There was only the faintest puff of wind and it was blowing from the northeast, so that any wolves at the den, or approaching it, would not be likely to get my scent. I settled myself among the spruces and scanned the floor of the ravine.

The entire area (an enclosure about thirty yards long by ten wide) was crisscrossed with trails. As I watched, two pups emerged from a jumble of shattered rocks under one wall of the ravine and scampered down one of the trails toward the tiny stream. They drew up alongside each other at the stream’s edge and plunged their blunt little faces into the water, wagging their stubby tails the while.

They had grown a good deal in the past weeks, and were now about the size of and roughly the same shape as full-grown groundhogs. They were so fat their legs seemed dwarfed, and their woolly gray coats of puppy hair made them look even more rotund. I could see no promise in them of the lithe and magnificent physique which characterized their parents.

A third pup emerged into view a little farther down the gully, dragging with him the well-chewed scapula of a caribou. He was growling over it as if it were alive and dangerous, and the pups by the stream heard him, lifted their dripping faces, and then bounced off in his direction.