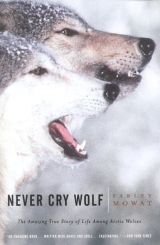

Текст книги "Never Cry Wolf"

Автор книги: Farley Mowat

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 5 (всего у книги 10 страниц)

Although I was much entertained by the spectacle of one of this continent’s most powerful carnivores hunting mice, I did not really take it seriously. I thought Angeline was only having fun; snacking, as it were. But when she had eaten some twenty-three mice I began to wonder. Mice are small, but twenty-three of them adds up to a fair-sized meal, even for a wolf.

It was only later, by putting two and two together, that I was able to bring myself to an acceptance of the obvious. The wolves of Wolf House Bay, and, by inference at least, all the Barren Land wolves who were raising families outside the summer caribou range, were living largely, if not almost entirely, on mice.

Only one point remained obscure, and that was how they transported the catch of mice (which in the course of an entire night must have amounted to a formidable number of individuals) back to the dens to feed the pups. I never did solve this problem until I met some of Mike’s relations. One of them, a charming fellow named Ootek, who became a close friend (and who was a first-rate, if untrained, naturalist), explained the mystery.

Since it was impossible for the wolves to carry the mice home externally, they did the next best thing and brought them home in their bellies. I had already noticed that when either George or Albert returned from a hunt they went straight to the den and crawled into it. Though I did not suspect it at the time, they were regurgitating the day’s rations, already partially digested.

Later in the summer, when the pups had abandoned the den in the esker, I several times saw one of the adult wolves regurgitating a meal for them. However, if I had not known what they were doing I probably would have misconstrued the action and still been no whit the wiser as to how the wolves carried home their spoils.

The discovery that mice constituted the major item in the wolves’ diet gave me a new interest in the mice themselves. I at once began a mouse-survey. The preliminary operation consisted of setting some hundred and fifty mousetraps in a nearby bog in order to obtain a representative sample of the mouse population in terms of sex, age, density and species. I chose an area of bog not far from my tent, on the theory that it would be typical of one of the bogs hunted over by the wolves, and also because it was close at hand and would therefore allow me to tend my traps frequently. This choice was a mistake. The second day my trap line was set, George happened in that direction.

I saw him coming and was undecided what to do. Since we were still scrupulously observing our mutual boundaries, I did not feel like dashing outside my enclave in an effort to head him off. On the other hand, I had no idea how he would react when he discovered that I had been poaching on his preserves.

When he reached the edge of the bog he snuffed about for a while, then cast a suspicious glance in my direction. Obviously he knew I had been trespassing but was at a loss to understand why. Making no attempt to hunt, he began walking through the cotton grass at the edge of the bog and I saw, to my horror, that he was heading straight for a cluster of ten traps set near the burrows of a lemming colony.

I had an instant flash of foreknowledge of what was going to happen, and without thought I leaped to my feet and yelled at the top of my voice:

“George! For God’s sake HOLD IT!”

It was too late. My shout only startled him and he broke into a trot. He went about ten paces on the level and then he began climbing an unseen ladder to the skies.

When, sometime later, I went over to examine the site, I found he had scored six traps out of the possible ten. They could have done him no real harm, of course, but the shock and pain of having a number of his toes nipped simultaneously by an unknown antagonist must have been considerable. For the first and only time that I knew him, George lost his dignity. Yipping like a dog who has caught his tail in a door, he streaked for home, shedding mousetraps like confetti as he went.

I felt very badly about the incident. It might easily have resulted in a serious rupture in our relations. That it did not do so I can only attribute to the fact that George’s sense of humor, which was well developed, led him to accept the affair as a crude practical joke—of the kind to be expected from a human being.

11

Souris а la Cr к me

THE REALIZATION that the wolves’ summer diet consisted chiefly of mice did not conclude my work in the field of diatetics. I knew that the mouse—wolf relationship was a revolutionary one to science and would be treated with suspicion, and possibly with ridicule, unless it could be so thoroughly substantiated that there would be no room to doubt its validity.

I had already established two major points:

1. That wolves caught and ate mice.

2. That the small rodents were sufficiently numerous to support the wolf population.

There remained, however, a third point vital to the proof of my contention. This concerned the nutritional value of mice. It was imperative for me to prove that a diet of small rodents would suffice to maintain a large carnivore in good condition.

I recognized that this was not going to be an easy task. Only a controlled experiment would do, and since I could not exert the necessary control over the wolves, I was at a loss how to proceed. Had Mike still been in the vicinity I might have borrowed two of his Huskies and, by feeding one of them on mice alone and the other on caribou meat (if and when this became obtainable), and then subjecting both dogs to similar tests, I would have been able to adduce the proof for or against the validity of the mouse-wolf concept. But Mike was gone, and I had no idea when he might return.

For some days I pondered the problem, and then one morning, while I was preparing some lemmings and meadow mice as specimens, inspiration struck me. Despite the fact that man is not wholly carnivorous, I could see no valid reason why I should not use myself as a test subject. It was true that there was only one of me; but the difficulty this posed could be met by setting up two timed intervals, during one of which I would confine myself to a mouse diet while during a second period of equal length I would eat canned meat and fresh fish. At the end of each period I would run a series of physiological tests upon myself and finally compare the two sets of results. While not absolutely conclusive as far as wolves were concerned, evidence that my metabolic functions remained unimpaired under a mouse regimen would strongly indicate that wolves, too, could survive and function normally on the same diet.

There being no time like the present, I resolved to begin the experiment at once. Having cleaned the basinful of small corpses which remained from my morning session of mouse skinning, I placed them in a pot and hung it over my primus stove. The pot gave off a most delicate and delicious odor as the water boiled, and I was in excellent appetite by the time the stew was done.

Eating these small mammals presented something of a problem at first because of the numerous minute bones; however, I found that the bones could be chewed and swallowed without much difficulty. The taste of the mice—a purely subjective factor and not in the least relevant to the experiment—was pleasing, if rather bland. As the experiment progressed, this blandness led to a degree of boredom and a consequent loss of appetite and I was forced to seek variety in my methods of preparation.

Of the several recipes which I developed, the finest by far was Creamed Mouse, and in the event that any of my readers may be interested in personally exploiting this hitherto overlooked source of excellent animal protein, I give the recipe in full.

SOURIS А LA CRКME

INGREDIENTS:

One dozen fat mice

Salt and pepper

One cup white flour

Cloves

One piece sowbelly

Ethyl alcohol

[I should perhaps note that sowbelly is normally only available in the arctic, but ordinary salt pork can be substituted.]

Skin and gut the mice, but do not remove the heads; wash, then place in a pot with enough alcohol to cover the carcasses. Allow to marinate for about two hours. Cut sowbelly into small cubes and fry slowly until most of the fat has been rendered. Now remove the carcasses from the alcohol and roll them in a mixture of salt, pepper and flour; then place in frying pan and sautй for about five minutes (being careful not to allow the pan to get too hot, or the delicate meat will dry out and become tough and stringy). Now add a cup of alcohol and six or eight cloves. Cover the pan and allow to simmer slowly for fifteen minutes. The cream sauce can be made according to any standard recipe. When the sauce is ready, drench the carcasses with it, cover and allow to rest in a warm place for ten minutes before serving.

During the first week of the mouse diet I found that my vigor remained unimpaired, and that I suffered no apparent ill effects. However, I did begin to develop a craving for fats. It was this which made me realize that my experiment, up to this point, had been rendered partly invalid by an oversight—and one, moreover, which did my scientific training no credit. The wolves, as I should have remembered, ate the whole mouse; and my dissections had shown that these small rodents stored most of their fat in the abdominal cavity, adhering to the intestinal mesenteries, rather than subcutaneously or in the muscular tissue. It was an inexcusable error I had made, and I hastened to rectify it. From this time to the end of the experimental period I too ate the whole mouse, without the skin of course, and I found that my fat craving was considerably eased.

It was during the final stages of my mouse diet that Mike returned to his cabin. He brought with him a cousin of his, the young Eskimo, Ootek, who was to become my boon companion and who was to prove invaluable to me in my wolf researches. However, on my first encounter with Ootek I found him almost as reserved and difficult of approach as Mike had been, and in fact still remained.

I had made a trip back to the cabin to fetch some additional supplies and the sight of smoke rising from the chimney cheered me greatly, for, to tell the truth, there had been times when I would have enjoyed a little human companionship. When I entered the cabin Mike was frying a panful of venison steak, while Ootek looked on. They had been lucky enough to kill a stray animal some sixty miles to the north. After a somewhat awkward few minutes, during which Mike seemed to be hopefully trying to ignore my existence, I managed to break the ice and achieve an introduction to Ootek, who responded by sidling around to the other side of the table and putting as much distance between us as possible. These two then sat down to their dinner, and Mike eventually offered me a plate of fried steak too.

I would have enjoyed eating it, but I was still conducting my experiment, and so I had to refuse, after having first explained my reasons to Mike. He accepted my excuses with the inscrutable silence of his Eskimo ancestors, but he evidently passed on my explanation to Ootek, who, whatever he may have thought about it and me, reacted in a typical Eskimoan way. Late that evening when I was about to return to my observation tent, Ootek waylaid me outside the cabin. With a shy but charming smile he held out a small parcel wrapped in deerskin. Graciously I undid the sinew binding and examined the present; for such it was. It consisted of a clutch of five small blue eggs, undoubtedly belonging to one of the thrush species, though I could not be certain of the identification.

Grateful, but at a loss to understand the implications of the gift, I returned to the cabin and asked Mike.

“Eskimo thinks if man eat mice his parts get small like mice,” he explained reluctantly. “But if man eat eggs everything comes out all right. Ootek scared for you.”

I was in no position—lacking sufficient evidence—to know whether or not this was a mere superstition, but there is never any harm in taking precautions. Reasoning that the eggs (which weighed less than an ounce in toto) could not affect the validity of my mouse experiment, I broke them into a frying pan and made a minute omelette. The nesting season was well advanced by this time, and so were the eggs, but I ate them anyway and, since Ootek was watching keenly, I showed every evidence of relishing them.

Delight and relief were written large upon the broad and now smiling face of the Eskimo, who was probably convinced that he had saved me from a fate worse than death.

Though I never did manage to make Mike understand the importance and nature of my scientific work, I had no such difficulty with Ootek. Or rather, perhaps I should say that though he may not have understood it, he seemed from the first to share my conviction that it was important. Much later I discovered that Ootek was a minor shaman, or magic priest, in his own tribe; and he had assumed, from the tales told him by Mike and from what he saw with his own eyes, that I must be a shaman too; if of a somewhat unfamiliar variety. From his point of view this assumption provided an adequate explanation for most of my otherwise inexplicable activities, and it is just possible—though I hesitate to attribute any such selfish motives to Ootek—that by associating with me he hoped to enlarge his own knowledge of the esoteric practices of his vocation.

In any event, Ootek decided to attach himself to me; and the very next day he appeared at the wolf observation tent bringing with him his sleeping robe, and obviously prepared for a long visit. My fears that he would prove to be an encumbrance and a nuisance were soon dispelled. Ootek had been taught a few words of English by Mike, and his perceptivity was so excellent that we were soon able to establish rudimentary communications. He showed no surprise when he understood that I was devoting my time to studying wolves. In fact, he conveyed to me the information that he too was keenly interested in wolves, partly because his personal totem, or helping spirit, was Amarok, the Wolf Being.

Ootek turned out to be a tremendous help. He had none of the misconceptions about wolves which, taken en masse, comprise the body of accepted writ in our society. In fact he was so close to the beasts that he considered them his actual relations. Later, when I had learned some of his language and he had improved in his knowledge of mine, he told me that as a child of about five years he had been taken to a wolf den by his father, a shaman of repute, and had been left there for twenty-four hours, during which time he made friends with and played on terms of equality with the wolf pups, and was sniffed at but otherwise unmolested by the adult wolves.

It would have been unscientific for me to have accepted all the things he told me about wolves without auxiliary proof, but I found that when such proof was obtainable he was invariably right.

12

Spirit of the Wolf

OOTEK’S ACCEPTANCE of me had an ameliorating effect upon Mike’s attitude. Although Mike continued to harbor a deep-rooted suspicion that I was not quite right in the head and might yet prove dangerous unless closely watched, he loosened up as much as his taciturn nature would permit and tried to be co-operative. This was a great boon to me, for I was able to enlist his aid as an interpreter between Ootek and myself.

Ootek had a great deal to add to my knowledge of wolves’ food habits. Having confirmed what I had already discovered about the role mice played in their diet, he told me that wolves also ate great numbers of ground squirrels and at times even seemed to prefer them to caribou.

These ground squirrels are abundant throughout most of the arctic, although Wolf House Bay lies just south of their range. They are close relatives of the common gopher of the western plains, but unlike the gopher they have a very poor sense of self-preservation. Consequently they fall easy prey to wolves and foxes. In summer, when they are well fed and fat, they may weigh as much as two pounds, so that a wolf can often kill enough of them to make a good meal with only a fraction of the energy expenditure involved in hunting caribou.

I had assumed that fishes could hardly enter largely into the wolves’ diet, but Ootek assured me I was wrong. He told me he had several times watched wolves fishing for jackfish or Northern pike. At spawning time in the spring these big fish, which sometimes weigh as much as forty pounds, invade the intricate network of narrow channels in boggy marshes along the lake shores.

When a wolf decides to go after them he jumps into one of the larger channels and wades upstream, splashing mightily as he goes, and driving the pike ahead of him into progressively narrower and shallower channels. Eventually the fish realizes its danger and turns to make a dash for open water; but the wolf stands in its way and one quick chop of those great jaws is enough to break the back of even the largest pike. Ootek told me he once watched a wolf catch seven large pike in less than an hour.

Wolves also caught suckers when these sluggish fish were making their spawning runs up the tundra streams, he said; but the wolf’s technique in this case was to crouch on a rock in a shallow section of the stream and snatch up the suckers as they passed—a method rather similar to that employed by bears when they are catching salmon.

Another although minor source of food consisted of arctic sculpins: small fishes which lurk under rocks in shoal water. The wolves caught these by wading along the shore and turning over the rocks with paws or nose, snapping up the exposed sculpins before they could escape.

Later in the summer I was able to confirm Ootek’s account of the sculpin fishery when I watched Uncle Albert spend part of an afternoon engaged in it. Unfortunately, I never did see wolves catch pike; but, having heard how they did it from Ootek, I tried it myself with considerable success, imitating the reported actions of the wolves in all respects, except that I used a short spear, instead of my teeth, with which to administer the coup de grвce.

These sidelights on the lupine character were fascinating, but it was when we came to a discussion of the role played by caribou in the life of the wolf that Ootek really opened my eyes.

The wolf and the caribou were so closely linked, he told me, that they were almost a single entity. He explained what he meant by telling me a story which sounded a little like something out of the Old Testament; but which, so Mike assured me, was a part of the semi-religious folklore of the inland Eskimos, who, alas for their immortal souls, were still happily heathen.

Here, paraphrased, is Ootek’s tale.

“In the beginning there was a Woman and a Man, and nothing else walked or swam or flew in the world until one day the Woman dug a great hole in the ground and began fishing in it. One by one she pulled out all the animals, and the last one she pulled out of the hole was the caribou. Then Kaila, who is the God of the Sky, told the woman the caribou was the greatest gift of all, for the caribou would be the sustenance of man.

“The Woman set the caribou free and ordered it to go out over the land and multiply, and the caribou did as the Woman said; and in time the land was filled with caribou, so the sons of the Woman hunted well, and they were fed and clothed and had good skin tents to live in, all from the caribou.

“The sons of the Woman hunted only the big, fat caribou, for they had no wish to kill the weak and the small and the sick, since these were no good to eat, nor were their skins much good. And, after a time, it happened that the sick and the weak came to outnumber the fat and the strong, and when the sons saw this they were dismayed and they complained to the Woman.

“Then the Woman made magic and spoke to Kaila and said: ‘Your work is no good, for the caribou grow weak and sick, and if we eat them we must grow weak and sick also.’

“Kaila heard, and he said ‘My work is good. I shall tell Amorak [the spirit of the Wolf], and he shall tell his children, and they will eat the sick and the weak and the small caribou, so that the land will be left for the fat and the good ones.’

“And this is what happened, and this is why the caribou and the wolf are one; for the caribou feeds the wolf, but it is the wolf who keeps the caribou strong.”

I was slightly stunned by this story, for I was not prepared to have an unlettered and untutored Eskimo give me a lecture, even in parable form, illustrating the theory of survival of the fittest through the agency of natural selection. In any event, I was skeptical about the happy relationship which Ootek postulated as existing between caribou and wolf. Although I had already been disabused of the truth of a good many scientifically established beliefs about wolves by my own recent experiences, I could hardly believe that the all-powerful and intelligent wolf would limit his predation on the caribou herds to culling the sick and the infirm when he could, presumably, take his choice of the fattest and most succulent individuals. Furthermore, I had what I thought was excellent ammunition with which to demolish Ootek’s thesis.

“Ask him then,” I told Mike, “how come there are so many skeletons of big and evidently healthy caribou scattered around the cabin and all over the tundra for miles to the north of here.”

“Don’t need to ask him that,” Mike replied with unabashed candor. “It was me killed those deer. I got fourteen dogs to feed and it takes maybe two, three caribou a week for that. I got to feed myself too. And then, I got to kill lots of deer everywhere all over the trapping country. I set four, five traps around each deer like that and get plenty foxes when they come to feed. It is no use for me to shoot skinny caribou. What I got to have is the big fat ones.”

I was staggered. “How many do you think you kill in a year?” I asked.

Mike grinned proudly. “I’m pretty damn good shot. Kill maybe two, three hundred, maybe more.”

When I had partially recovered from that one, I asked him if this was the usual thing for trappers.

“Every trapper got to do the same,” he said. “Indians, white men, all the way down south far as caribou go in the wintertime, they got to kill lots of them or they can’t trap no good. Of course they not all the time lucky to get enough caribou; then they got to feed the dogs on fish. But dogs can’t work good on fish—get weak and sick and can’t haul no loads. Caribou is better.”

I knew from having studied the files at Ottawa that there were eighteen hundred trappers in those portions of Saskatchewan, Manitoba, and southern Keewatin which composed the winter range of the Keewatin caribou herd. I also knew that many of these trappers had been polled by Ottawa, through the agency of the fur trading companies, for information which might help explain the rapid decline in the size of the Keewatin caribou herd. I had read the results of this poll. To a man, the trappers and traders denied that they killed more than one or two caribou a year; and to a man they had insisted that wolves slaughtered the deer in untold thousands.

Although mathematics have never been my strong point, I tried to work out some totals from the information at hand. Being a naturally conservative fellow, I cut the number of trappers in half, and then cut Mike’s annual caribou kill in half, before multiplying the two. No matter how many times I multiplied, I kept coming up with the fantastic figure of 112,000 animals killed by trappers in this area every year.

I realized it was not a figure I could use in my reports—not unless I wished to be posted to the Galopagos Islands to conduct a ten-year study on tortoise ticks.

In any event, what Mike and Ootek had told me was largely hearsay evidence, and this was not what I was employed to gather. Resolutely I put these disturbing revelations out of mind, and went back to learning the truth the hard way.

13

Wolf Talk

OOTEK HAD many singular attributes as a naturalist, not the least of which was his apparent ability to understand wolf language.

Before I met Ootek I had already noted that the variety and range of the vocal noises made by George, Angeline and Uncle Albert far surpassed the ability of any other animals I knew about save man alone. In my notebooks I had recorded the following categories of sounds: Howls, wails, quavers, whines, grunts, growls, yips and barks. Within each of these categories I had recognized, but had been unable adequately to describe, innumerable variations. I was also aware that canines in general are able to hear, and presumably to make, noises both above and below the range of human registry; the so-called “soundless” dog-whistle which is commercially available being a case in point. I knew too that individual wolves from my family group appeared to react in an intelligent manner to sounds made by other wolves; although I had no certain evidence that these sounds were anything more than simple signals.

My real education in lupine linguistics began a few days after Ootek’s arrival. The two of us had been observing the wolf den for several hours without seeing anything of note. It was a dead-calm day, so that the flies had reached plague proportions, and Angeline and the pups had retired to the den to escape while both males, exhausted after a hunt which had lasted into mid-morning, were sleeping nearby. I was getting bored and sleepy myself when Ootek suddenly cupped his hands to his ears and began to listen intently.

I could hear nothing, and I had no idea what had caught his attention until he said: “Listen, the wolves are talking!” and pointed toward a range of hills some five miles to the north of us.*3

I listened, but if a wolf was broadcasting from those hills he was not on my wavelength. I heard nothing except the baleful buzzing of mosquitoes; but George, who had been sleeping on the crest of the esker, suddenly sat up, cocked his ears forward and pointed his long muzzle toward the north. After a minute or two he threw back his head and howled; a long, quavering howl which started low and ended on the highest note my ears would register.

Ootek grabbed my arm and broke into a delighted grin.

“Caribou are coming; the wolf says so!”

I got the gist of this, but not much more than the gist, and it was not until we returned to the cabin and I again had Mike’s services as an interpreter that I learned the full story.

According to Ootek, a wolf living in the next territory to the north had not only informed our wolves that the long-awaited caribou had started to move south, but had even indicated where they were at the moment. To make the story even more improbable, this wolf had not actually seen the caribou himself, but had simply been passing on a report received from a still more distant wolf. George, having heard and understood, had then passed on the good news in his turn.

I am incredulous by nature and by training, and I made no secret of my amusement at the naпvetй of Ootek’s attempt to impress me with this fantastic yarn. But if I was incredulous, Mike was not. Without more ado he began packing up for a hunting trip.

I was not surprised at his anxiety to kill a deer, for I had learned one truth by now, that he, as well as every other human being on the Barrens, was a meat eater who lived almost exclusively on caribou when they were available; but I was amazed that he should be willing to make a two-or three-day hike over the tundra on evidence as wild as that which Ootek offered. I said as much, but Mike went taciturn and left without another word.

Three days later, when I saw him again, he offered me a haunch of venison and a pot of caribou tongues. He also told me he had found the caribou exactly where Ootek, interpreting the wolf message, had said they would be—on the shores of a lake called Kooiak some forty miles northeast of the cabin.

I knew this had to be coincidence. But being curious as to how far Mike would go, to pull my leg, I feigned conversion and asked him to tell me more about Ootek’s uncanny skill.

Mike obliged. He explained that the wolves not only possessed the ability to communicate over great distances but, so he insisted, could “talk” almost as well as we could. He admitted that he himself could neither hear all the sounds they made, nor understand most of them, but he said some Eskimos, and Ootek in particular, could hear and understand so well that they could quite literally converse with wolves.

I mulled this information over for a while and concluded that anything this pair told me from then on would have to be recorded with a heavy sprinkling of question marks.

However, the niggling idea kept recurring that there just might be something in it all, so I asked Mike to tell Ootek to keep track of what our wolves said in future, and, through Mike, to keep me informed.

The next morning when we arrived at the den there was no sign of either of the male wolves. Angeline and the pups were up and about, but Angeline seemed ill at ease. She kept making short trips to the crest of the den ridge, where she stood in a listening attitude for a few minutes before returning to the pups. Time passed, and George and Uncle Albert were considerably overdue. Then, on her fifth trip to the ridge, Angeline appeared to hear something. So did Ootek. Once more he went through his theatrical performance of cupping both ears. After listening a moment he proceeded to try to give me an explanation of what was going on. Alas, we were not yet sufficiently en rapport, and this time I did not even get the gist of what he was saying.

I went back to my observing routine, while Ootek crawled into the tent for a sleep. I noted in my log that George and Uncle Albert arrived back at the den together, obviously exhausted, at 12:17 P.M. About 2:00 P.M. Ootek woke up and made amends for his dereliction of duty by brewing me a pot of tea.