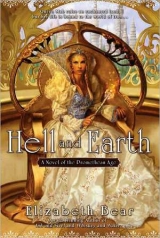

Текст книги "Hell and Earth"

Автор книги: Elizabeth Bear

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 11 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

“There’s a ritual of sacred marriage,” Murchaud offered slowly, after a long pause.

“A barren. marriage ‘twould be, between thee and me.” Kit shook his head. “My problem is Mehiel. I think I could bear mine own discomfort, to speak quite plainly. His–the distress of angels–is something else.”

“And what would it take to free Mehiel, then?”

Kit leaned forward. He pulled the chess piece from the glass and sucked the wine from its surface, then polished it dry on his handkerchief. He set it down on the tabletop with a pronounced, careful click, amazed at his own calm. “He’ll have to come out sooner or later, I suppose. And it would frustrate all our enemies enormously–Lucifer, the Prometheans, the lot.”

“Kit?”

“My death, Murchaud. It will take my death, I am told.”

Act V, scene ii

Some holy angel

Fly to the court of England and unfold

His message ere he come, that a swift blessing

May soon return to this our suffering country.

–William Shakespeare, Macbeth,Act III, scene vi

Alas, my Romeo–

– the Mebd is no better; I have visited her with poetry to comfort her weary hoard, & she seems somehow… faded. We must contrive to convince the world of the currency of Faerie Queenes. I don’t suppose a revival of thyMidsummer Night’s Dream might be possible?

I hear what thou sayest of James; I suppose thou knowest there are rumors that he finds his favorites among the young men at court. It might be worth thy while to befriend such, as they will have His Majesty’s–attention– & if the Queen is so fond of Ben ‘d work, then it may well be that Ben can find succor for our projects with her.

You might visit Sir Walter in his immurement, if he is permitted guests– I know Southampton was–for if he be nothing else, Raleigh is a poet and a poet sympathetic to our cause. & clever in politics. Gloriana is gone: we are not just for England now, but for Eternity, our little band of less‑mad Prometheans.

I will rejoin your Bible studies, of course. Even working piecemeal and catch as catch can, methinks we’ve accomplished too much to abandon our plans now.

My kindest regards to thee and to thine Annie, to little Mary and her Robin, to Tom and Audrey and George and Sir Walter should you see him. And my love most especially to Ben.

– in affection,

thy Mercutio

Will made his final exit on cue and elbowed John Fletcher in the ribs in passing as he quit the Globe’s high stage. “By Christ,” he said, as Fletcher slapped him across the back, “another plague summer. I can’t bear touring another year, John. On top of learning six new plays in repertory. Ah well. At least they’ve more or less mastered Timon,which has to recommend it that ‘tis not Sejanusagain. Gah–” Will scrubbed sweat from his face on a flannel and tossed it away. “How are we to endure it?”

“Because we have no choice.” Fletcher tucked a stray strand of hair behind his ear, revealing a half‑moon of moisture under the arm of his shirt. In the unseasonable June of 1604 he’d left his habitual crimson doublet thrown over the back of a nearby chair. “Speaking of Sejanus,at least Ben is behaving himself of late.”

“If thou deemst getting himself fined for recusancy again behaving.”

“At least he’s not getting the playhouses shut down.”

“No,” Will answered bitterly, thinking of Baines’ faction and the endless stalemate fought back and forth between the groups of Prometheans. “The plague manages that just fine.” He unbuttoned his doublet, opening the placket to entice some breath of cool air in. “Come, Jack. I’ll stand thee a drink.”

John caught up his doublet and regarded it with distaste. “Tell me it will be cooler in the Mermaid and I’ll follow thee anywhere.” He took Will’s arm, steadying him down the stair.

“I doubt it’s cooler in the Thames. Or any better smelling. I wonder what Ben thinks he’s about. I should not like to be Catholic in England under James.” Will bit his lip in silent worry – for Edmund more than Ben. Ben wasn’t the only one who could stand to hide his sympathies a little better.

“‘Tis true. It’s hard to believe it could be worse than under Elizabeth. …” They came out into the sunlight, and John looked doubtfully toward the crowds along the way to London Bridge. “By water?”

“Indeed.” Even with his cane to steady him, and the new strength in his strides that led him to believe there was something more sinister than merely an unfortunate patrimony behind his palsy, Will didn’t intend to brave the long walk in the afternoon heat. “I suppose bankrupting the Catholics with fines is one way to deal with it. Still, Ben’s tastes in religion don’t seem to affect his popularity at court. Well, now that the problem of Sejanusis settled.” It had, Will must admit, been in questionable taste to deliver a play on the downfall of a sodomite Emperor’s favorite to the stage just as a reputedly sodomitical King was coming to the throne. Still, it wasn’t as if James could claim to be the target of the satire, and Ben had weathered the inquisitions well enough, all wide‑eyed pretense at innocence.

“There is a divide,” Fletcher noted, “between Queen Anne’s entertainments and King James’ policy.” And that was where the conversation ended along with their privacy to speak freely, for they embarked on the wherry to cross the Thames.

The Mermaid was cooler than the Globe, in fact, and if possibly not cooler than the Thames, fresh rushes and sawdust on the floor assured it wasbetter‑smelling. And–as if Will’s very conversations were attaining some magic with the raw new power that charged his poetry–the tavern was empty of all save the landlord and Edmund Shakespeare, who sat on a bench against the wall, pushing turnips about in his stew.

“Ted!” Fletcher pushed Will unceremoniously toward his brother and went to ask the landlord for dinner and ale.

“Jack,” Edmund answered. “Will, come sit.”

Will remembered something and turned over his shoulder. “John, I said I’d stand the meal–”

“Stand it tomorrow,” Fletcher answered, juggling two tankards as he returned. “Henslowe paid on time, for once. Ted Shakespeare, that’s an interesting expression thou’rt wearing. What news?”

Will blinked, and glanced back at his youngest brother. It wasa knowing expression, as catlike smug as anything Kit might have worn. “All right, Edmund.” He tasted his ale, which was dark and sweet. “Fletcher’s right. I can see the mouse’s tail through thy teeth. Out with it.”

Edmund let his grin broaden until it stretched his cheeks. He took a swallow of his ale and waited for silence, then fixed Will with a steady gaze. “Edward de Vere is dead.”

Edmund’s timing was precise, and Will sprayed ale across the table. “Oxford?” he spluttered, reaching for his handkerchief.

“Aye.”

“How?”

“Plague.”

Of course.Will dabbed his chin and the table dry, and picked up his ale again. When one outlived one’s usefulness to the dark Prometheans, they are not shy about making it plain.Will hefted his tankard thoughtfully and clinked it against Edmund’s.

“To the former Earl of Oxford,” Edmund said. “And not a moment too soon. They say he died very nearly in penury: he’s had to sell all his properties, and left almost nothing to his son.” His eyebrows went up; he looked to Will. And Will sucked his own lower lip, thinking that those who played politics danced with a snake that swallowed itself.

“I didn’t know you were acquainted with the Earl, ” Fletcher said, as the landlord brought their supper to the board.

“Aye,” Will said. “Unpleasantly so.” He wished he found the news more comforting: the end of an old enemy. But all it confirmed was what he had suspected. The Prometheans were moving–again–and Will hadn’t the slightest idea what about, or how to stop them.

This was easier when I had someone to tell me what to do,he thought, and picked up his bread and his spoon. And laid them down once more, hands shaking with the realization that it wasn’t necessarily the Prometheans who were responsible for the death of Edward de Vere, now that the Earl was utterly without the royal protection that had kept him alive so long.

Kit would have told me if he were contemplating cold‑blooded murder.

Wouldn’t he?

Act V, scene iii

As for myself, I walk abroad o ‘ nights

And kill sick people groaning under walls:

Sometimes I go about and poison wells.

– Christopher Marlowe, The Jew of Malta,Act II, scene iii

Edward de Vere, Kit thought with a certain cool satisfaction, did not look well at all. But he didn’t think the man was sick with plague, as had been put about. Rather Oxford looked … shrunken, against the rich brocades of his sweet‑smelling bed. He seemed as if he dozed, a book open on his lap, and he did not look up when Kit stepped through the Darkling Glass and into the shadows at the corner of the room.

Kit cleared his throat, right hand across his waist and resting on the hilt of his rapier. “How does it feel to be ending your life on charity, my lord?”

The Earl of Oxford awoke with a start, the book snapping shut as his body twitched. He blinked and struggled to push himself upright against the pillows as Kit came out into the sunlight, but his arms seemed to fail him and his face contorted in pain. “Kit Merlin,” he said in wonder, his voice unsteady. “Of all the faces I did not look for–”

And even be cannot recall my name.

“I wasn’t looking for thee either,” Kit admitted, lounging against the bedpost. He let his hand fall away from his hilt. The carved wood wore into his shoulder, a reassuring discomfort. He pressed himself against it, parting the bed curtains, and with his right eye saw the light of strength draining from a man he used to fancy was his lover. “The Darkling Glass sent me here.”

“Sent thee?”

Kit took pity on the struggling Earl and moved forward, propping the pillows behind thin shoulders. It was like touching a poppet, a bundle of kindling wrapped in a silk nightgown. “Aye.” Grudging. “I was looking for Richard Baines. It showed me thee.”

Oxford nodded weakly. “He’s warded against thee–”

“He’s warded in general.” Something stirred in Kit’s breast. He closed his eyes, leaning heavily on the head of the bed as a wave of dizziness exhausted him. “Edward, how dost thou bear the weight of thine own skin?”

“My skin, or my sin?” It was a weak chuckle, barely an effort. From his right eye, Kit could see how the darkness within Oxford seemed fit to devour the fragile, flickering candle flame that was his life. “It matters not. Baines is consuming me.”

“I see that.” Kit tugged Oxford’s covers higher, then wiped his own hands fastidiously on his breeches. “Thou wert never better than an adequate poet, Edward. What made thee think thou couldst turn thy back on Prometheus, and live?”

“Kit,” Oxford said, and held forth a knotty hand. Kit took it, oily paper over bone. “Why thinkst thou I meant to live?”

An excellent question. Kit sat himself down on the edge of the bed and laced his fingers around his knee. “I loved thee, thou bastard,” he said in what was not meant to be a whisper.

“Pity, that.”

“Thou’lt never know how great a one. I hope thou knowest what thou spurned, my Edward.”

Oxford’s mouth twisted; Kit thought it was pain. “A bit of a poet and a catamite?” de Vere asked, and Kit flinched.

“Christofer Marley,” he said. Naming himself as if the name meant something. “A name to conjure with, or so I am assured.”

“Why didst thou come here? To mock me on my deathbed?”

Kit bit his lower lip savagely. This is not going well.“To discover why thou didst appear in my glass when I sought Richard Baines.”

Oxford laughed. It might have been a cough. “Because I can tell thee something about the Prometheans.”

“Aye?”

“Aye,” de Vere said. “What is Prometheus but knowledge?” He coughed, and had not the strength to cover his mouth with his hands. “What is God but mercy?”

“Is God that?” But the light in his breast flared into savagery, and–unwitting–Kit laid a hand on Oxford’s shoulder. It was not his own hand, quite: he could see the glare and the power gleaming behind the fingernails. Mehiel. God’s pity, at least. Does Oxford deserve that?

“When we need him to be.” Oxford smiled, his teeth white as whittled pegs behind liver‑colored lips. “Those that steal from the gods, those that defy God, they are punished. How couldst thou, with the divine fire of thy words, expect to escape?”

Kit thought of Lucifer’s exquisite suffering, and nodded. “Aye. Punished.”

Oxford smiled, and Kit still knew him well enough to read the pleasure in his eyes. The pleasure of a chess player who has successfully anticipated his opponent. Kit blinked. “You summoned me.”

“Did I?”

“Aye.”

“Aye–” Oxford’s cough racked Kit as well, and both of them pressed their fingers to their mouths. “I summoned thee. I cry thee mercy, Kitten.”

“I owe thee nothing.”

“Except revenge?”

“It’s no longer worth it to me.” Vengeance is mine, sayeth the Lord.“Thou’rt dying.”

“I never said,” Oxford answered, his gaze perfectly level on Kit’s, “that thou shouldst seek vengeance on me. But there are other purposes my death might serve.”

“Baines is consuming me.”

Kit nodded, understanding. Then gasped as Mehiel answered Oxford’s words from within, a flare of panicked strength that Kit thought might stream from his fingertips, halo his head like the inverse of Lucifer’s shadowy crown. The angel–was afraid. And moved to pity, both. Don’t you remember bow this man used us, Mehiel? How he plotted to have us slain?“Thy death might serve my purposes quite well, Edward.”

“Didst ever ask thyself what Prometheus might want?”

“Other than a new liver?”

“Thy wit has always been thine undoing,” Oxford said tiredly. “Kit, mock me not when I have the will to aid thee, this one last time. Baines has used me as much as he has thee–”

“How fast they run to banish him I love, ”Kit said, just to see Oxford wince. “What, Edward? What does Prometheus want?”

“It’s a riddle. It depends on when thou dost meet him. Is he climbing to the heavens, or is he hurled back down? Is he chained on a rock, moaning for release? Would he seek immortality, or would he entreat thee take it from him, and make him but a mortal man again?”

Kit shook his head. Oxford was always one to speak in riddles, enjoying teasing others with what he knew and they didn’t, and Kit had no stomach for it now. “What vile task wilt thou bid me to? Why is’t I should not break thy wretched neck?”

“No reason,” Oxford answered. “Do.”

“Do what?”

“Do break my neck. If that is how thou preferest to end this.” Oxford’s hands pleated the blankets across his thighs. “I did serve England–”

“Thou didst serve thyself and thine own furtherance. The Prometheans were meant to seek God and the betterment of Man, thou bastard. Thou–” Kit swallowed the shrillness that wanted to fill his voice. “Thou wert nothing but a spendthrift, a wastrel, a posturing cockerel.”

“Think it as thou wilt.” A sigh, exhaustion. The traceries of light that tangled Oxford were nothing like the dull red of the fever that had so nearly killed Will. “I will not serve MasterRichard Baines, once ordained a priest. Kill me, Kitten.”

A blatant request, and Kit blinked on it. “Killthee.”

“Aye.” Fumbling, Oxford tried to pluck the pillow from behind his neck. Kit helped him with it, careful not to touch the Earl’s fevered skin as Oxford lay back flat. Kit stepped back, the pillow clutched to his chest. Oxford closed his eyes. “Wilt let Baines have the use of me, Kitten? Kill me tonight.”

God,Kit thought. I’d imagined this as somehow satisfying.He looked down at the pillow in his hands and closed his eyes.

Amaranth’s touch did not trouble Kit in the slightest, perhaps because she was more beast than woman. So when he was done with Edward de Vere and had left the Earl of Oxford’s body laid out tidily under the coverlet of his borrowed bed, it was Amaranth that Kit sought.

She lay on her back on the grass under the honey‑scented tree that had been Robin Goodfellow, the creamy white scales of her belly exposed to the dappled sun and her slender, maidenly arms stretched high over her head. She wore a shirt of thin white lawn spotted with embroidered violets, startlingly feminine on a creature that was anything but. Kit dropped into the grass beside her, far enough away that he wouldn’t startle her hair, and crossed his legs, leaning forward with his elbows on his knees and his chin in his hands. She twitched her tail, acknowledging him without opening her eyes, and tapped a coil against his hip.

“Thou’rt pensive, Sir Poet.”

“I am more than pensive. I am troubled.”

Her scales were soft and leathery, warmer than the grass when he ran his hands over it. As comforting as a hot‑sided beast in a byre, and she smelled of autumn leaves or curing tobacco, musky as civet; mingled with the sweetness of the flowers, it put Kit in mind of expensive perfume. He lay down on the grass, his head propped on his knuckles, and sighed. She reached down lazily and stroked his hair. “And what troubles thee, Kit?”

“Prometheus,” he said, leaning into the luxury of a touch that did not make him cringe. She shifted to pillow his head on her coils, the gesture more motherly than predatory. “Someone has made an interesting suggestion to me, just now.”

“Interesting?”

Her voice was drowsy in the warmth; it relaxed him as smoothly as if it were a spell. “What if Prometheus–as in, the Prometheus Club–were a person, an individual. A role. As much as he is a symbol of what they intend to accomplish, that is to say, stealing fire from the gods? Or God? And if so, what are we to do about it?”

Sss.” A ripple of muscular constriction passed down her length. Her hand stilled in his hair for a moment, and then resumed smoothing the tangles that always formed at the back of his neck, where his hair snagged on his collar. “Comest thou to a snake for sympathy, Sir Poet?”

“I come to a snake for information. Which may be equally foolish.”

She laughed and levered herself upright without disturbing the section of coils upon which Kit rested. He rolled on his back, her wide belly scales denting under the weight of his head, and looked up her human torso as she rose. Sunlight shone through the cobweb lawn of her shirt; it bellied out on a breeze, offering him a glimpse of her maidenly belly and the underside of her breasts, the embroidered violets casting shadows like spots upon her skin.

“Come along,” she said, and gave a little shudder to shake him to his feet. He rose, dusting bits of grass from his doublet, and fell into step beside her.

She led him down the bluff by the water, holding his hand–her arm extended to keep him well away from any aggressive gestures from her hair–and across the sand. “Wait,” he said, and stripped off his boots and ungartered his stockings so he could feel the sand between his toes. Amaranth didn’t stop, but slithered forward at a stately place, leaving a wavy line through the sand. Kit had only to walk a little faster to catch up. “What is it thou dost not wish the Puck‑tree to overhear, Amaranth?”

“There is a Prometheus,” she said, and turned to look at him through matte steel‑colored eyes. She smiled liplessly. “Ask me another mystery, man.”

He swallowed. The sea broke over her bulk and foamed around his bare feet, drawing the sand from under his soles as if sucked by mouths. “Where do I find this Prometheus?”

The white foam ran down her dappled sides. She bent to trail her fingers through the waves. “In the mirror, Sir Christofer. In the eyes of a lover. Under an angel’s bright wings. All of those places and none. One more question. Come.”

I’ve fallen into a fairy tale.“How did I earn three questions of a serpent, my lady Amaranth?”

“Is that the question thou wishst to waste?” But her voice was kind, a little mocking. “I shall not count the answer, though. The answer. Which is, thou hast earned nothing, but this I give thee as a gift. Ask.”

Another wave, and this one wet him to the knee, spray salting his cheek and lips. The flavor was as musky as the lamia’s scent, salt and depth and thousands of deaths over thousands of years, all washed down into the endless, consuming sea. Kit shivered. And if everything has a spirit, what do you suppose the ocean’s soul is like?His chin lifted, as if of its own accord, and he turned to look out over the sea and its breakers like white tossing manes on dark stallions’ necks.

Amaranth coiled around him, an Archimedean screw with Kit the column at its center, and rested her seashell fingers on his shoulder, her head topping his by two feet or more. “Ask,” and the hiss of her voice was the hiss of the waves.

“What magic is a sacred marriage capable of, Amaranth?”

“Ah.” She settled in a ring about him, a hollow conduit with a poet at its center, sunlight glazing her scales as it did the dimples on the surface of the sea. “A grave risk, such a ritual. To work, it would need to be more than a ritual sacrifice. Thou wouldst die of it, who was Christofer Marley.”

“A grave risk. And? ”

“A potential triumph. It could be salvation: it’s so hard to tell. So much depends on–”

The waves came and went.

“Circumstance? ”

“Mehiel, ” she answered. “Mehiel, and how badly tormented the heart or the soul of an angel might be.”

“Badly,” Kit answered, but he was thinking of Lucifer Morningstar and not the sudden, fearsome heat and pressure in his chest.

Act V, scene iv

To this I witness call the fools of time

Which die for goodness, who have Lived for crime …

–William Shakespeare, from Sonnet 124

Will held his wrist out, turned over so the unworked buttons showed. “Ted, couldst see to these? Thank thee–”

“Court clothes,” Edmund said. “So high and mighty is my brother now–”

“Hah.” Will picked his wine up with his other hand and drained the goblet down to the bitter, aconite‑flavored dregs. He polished the cup with his handkerchief and set it on the trestle, upside down. “I am summoned to attend, is all. The King’s Men are no different at court from drawing‑room furniture: meant to fill up the corners, but hardly of any real use. Hast thou any news for me?

“Robin Poley,” Edmund said, fastening the final button on Will’s splendid doublet.

“Robin Poley? Or Robert Poley?”

“The elder.”

“What of him?”

“Is a Yeoman of the Guard of the Tower of London now.”

Will paused in the act of tugging his sleeve down over his shirt cuff. “… really.”

“Aye. Cecil’s doing, again. Although I suppose I must call Cecil the Earl of Salisbury now–”

“Where ears can hear, you must. Christ on the Cross. Sixteen hundred and five, and I have no better mind what old Lord Burghley’s second son is after than I did twelve years ago, Ted. He plays the white and black pieces both, a double game that defies all understanding. But he has got himself raised an Earl, so I suppose whatever his game might be, he is winning it. Do I look grand enough for church with a King?”

Edmund stepped back, sucking on his lower lip until he nodded once, judiciously. “Cecil’s at odds with the King, they say–”

“Aye.” Will checked the mirror over his mantel, and ran both hands along the sides of his neck to pluck what remained of his hair from his collar. “Well, is and is not. The King wants Scots around him, but he needsSalisbury. What he’s got is good Calvinists, and he’s still urging that the Bishops be diligent in their pursuit of Catholics.” For all his own proclivities are not so Calvinist as that. Gloriana’s failings were what they were, but she was never a hypocrite.Will stopped, and fixed Edmund with a look. I wrote to Anne and told her to see she got herself and the girls to church, Edmund. And I want to see thee in attendance too.”

“Will–” Edmund sighed. “‘Tis my faith thou dost so lightly dismiss.”

“Aye,” Will answered. “And I am eldest now, with Father gone, and thou dost owe me that much duty. Thy life is worth more, and thy family’s safety. Catholicism has been outlawed,Edmund. Recusants are not tolerated now. You will obey me.”

“What’s a life worth without faith?” Edmund looked Will square in the eye, but Will would not glance down.

“I won’t forbid thee whatever–diversions–thou dost seek,” Will said. “But thou wilt to Church. I’ll not see thee stocked or hanged.”

His brother matched gazes with Will for what seemed like an hour, but Will–frankly–had the weight of experience. And the authority of the eldest son behind his edict. Edmund dropped his eyes to the floor.

“As you bid.” Edmund glanced up again as a church bell tolled the hour. “And now thou must hurry. Or thou wilt be late for thy King.”

Infirmity, if not age, granted Will the consideration of a stool in the corner near the fire, but he found it rather warm for a midmorning. Especially when Burbage, also resplendent in James’ livery, had cleverly staked out the corner nearest the wine on the sideboard – incidentally doing his usual fine job of framing himself against dark wood that showed off his fair curls to advantage.

If it weren’t for the King’s scarlet, however, Will would vanish against the paneling like a ghost. Which suited his mood admirably, come to think of it; his mood was fey, and dark lines of poetry taunted him.

Burbage refilled his goblet a second time before Will could think to forbid it, and Will swore himself solemnly to drink no more after this last cup. “Thou’lt have me drunk before the King, Richard,” he said from the corner of his mouth.

Matters not,” Burbage answered. “I’m drunk every day, and it’s done me no harm–”

“Not until thou diest of yellow jaundice,” Will said dryly. “Or thy belly swells up like a berry full of juice.”

“Well, a man’s got to die of something.” That bit of philosophy accomplished, Burbage turned to check Will’s reaction. “The King,” he hissed, and dropped a flourishing bow even as Will was turning to make his own obeisance.

“Your Highness,” Will and Burbage said, speaking in unison as if rehearsed. And after fifteen years playing together, ‘tis no surprise if we pick up the cue.

“Master Players.” James the First of England had ruddy cheeks, contrasting with slack, pale skin and a sad‑eyed, wary expression. Will thought he looked haunted, and he had not lost a trace of his thick Scottish accent in two years in the south. Can we hope you are about plotting some new masterwork to entertain us with?”

“Always plotting,” Will answered. “What would please the King?”

James made a bit of a show of thinking. “You know our Annie loves masques and divertissements. We had Ben Jonson’s Masque of Blacknessat court just this winter past. But perhaps something a little more exciting, for the lads. I worry a bit at their mother’s influence: women are such frivolous things, and she has her ideas.”

“Ideas, Your Highness?” Will was grateful that Burbage spoke to fill the King’s expectant silence.

“I fear being so beset by witches as we were at our old lodgings has made her dependent on Papist rituals to keep ill spirits away,” James said frankly, dropping into the informal speech that was his habit. “Silly conceits, and a woman will have them. But I do not want her leading my boys from good Protestant ethics. I’ll see my little Elizabeth crowned queen before Henry or Charles king, if she turns them Catholic.” The King shrugged, carelessly tipping some drops of wine over the edge of his cup. “So perhaps something with Scottish kings and the mischief of witchcraft–”

“Do you have a plot in mind, Your Highness?”

“We saw a Latin trifle at Oxford at the beginning of the month. That Ouinn fellow. You know him?”

“Tres Sybillae. ”

“That’s the one.”

“Your Highness wishes a play about King MacBeth.”

“The usurper, rightfully deposed.” It was a gentle rebuke, as such things went, delivered with a smile. The King turned to acknowledge Robert Cecil as the new Earl of Salisbury came up alongside him. “It will serve a welcome distraction in a time of plague. I’ve prorogued Parliament for fear of it: we’ll meet in colder weather. And a good morning to you, my fine Earl Elf. What think you of the fifth of November?”

“It’s a fine day for a hanging, I suppose. Or did you have something else in mind, Your Highness?”

“Parliament. We’ll have some bills come due that must be paid, sooner rather than later–”

“Ah, yes.” Salisbury nodded an acknowledgement as Will filled a cup for him and dropped a bit of sugarloaf in. “Thank you, Master Shakespeare. I think we must talk a bit about expenditures too, Your Highness.”

The King snorted. “A parsimonious elf. Canst not transform some oak leaves to gold, Salisbury, and refill our coffers?”

“Alas–” Salisbury laid a hand on the King’s elbow, and the two men turned aside. But Robert Cecil’s last tenacious glance told Will there would be another conversation, later, out of earshot of the King.

“Is he still opposed to thy Bible?” Burbage asked quietly, when the King and his minister were very well out of earshot.

Will blinked. “How didst thou know about the Bible, Richard?”

Richard Burbage paused, his cup frozen halfway to his mouth as his attention turned inward. He pursed his lips, and answered at last, “Mary Poley mentioned it to me as if it were common knowledge. I thought she must have had the word from thee.”

“No,” Will said, feeling his blood drain from his limbs. “I told her no such thing.”

Will wrote by candlelight, late into the warmth of the evening, and was not surprised when a familiar cough interrupted his study. “Good evening, Kit.”

“Hello, my love. I brought thee supper–”

Will glanced at the window surprised to see that twilight had faded to full dark. “Thou’rt considerate.”

“Thou’rt like to starve to death, an I did not. What is it has thy fancy so tightly, Will?” Kit laid his bundle on the edge or the table, well away from Will’s papers, and unwrapped linen to produce a pot of steaming onion soup and a half loaf of brown bread folded around a still‑cold lump of butter that was just melting at the edges.

“Fey food,” Will said, and pushed his papers aside. “Or the homely sort?”

“Both,” Kit answered. “Morgan’s cooking. Thou didst not answer my question – ”

“Oh, a tragedy,” Will answered. “Something to catch James’ fancy. Witches and prophecies. We have problems and problems, Kit. Thou didst not speak to Mary Poley of our testaments, didst thou?”