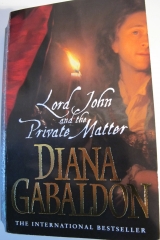

Текст книги "Lord John and the Private Matter "

Автор книги: Diana Gabaldon

Жанр:

Исторические приключения

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 17 страниц)

Lord John and Private Matter

by Diana Gabaldon

To Margaret Scott Gabaldon and Kay Fears Watkins,

my children’s wonderful grandmothers

Chapter 1

When First We Practice

to Deceive

London, June 1757

The Society for the Appreciation of

the English Beefsteak, a Gentlemen’s Club

It was the sort of thing one hopes momentarily that one has not really seen—because life would be so much more convenient if one hadn’t.

The thing was scarcely shocking in itself; Lord John Grey had seen worse, could see worse now, merely by stepping out of the Beefsteak into the street. The flower girl who’d sold him a bunch of violets on his way into the club had had a half-healed gash on the back of her hand, crusted and oozing. The doorman, a veteran of the Americas, had a livid tomahawk scar that ran from hairline to jaw, bisecting the socket of a blinded eye. By contrast, the sore on the Honorable Joseph Trevelyan’s privy member was quite small. Almost discreet.

“Not so deep as a well, nor so wide as a door,” Grey muttered to himself. “But it will suffice. Damn it.”

He emerged from behind the Chinese screen, lifting the violets to his nose. Their sweetness was no match for the pungent scent that followed him from the piss-pots. It was early June, and the Beefsteak, like every other establishment in London, reeked of beer and asparagus-pee.

Trevelyan had left the privacy of the Chinese screen before Lord John, unaware of the latter’s discovery. The Honorable Joseph stood across the dining room now, deep in conversation with Lord Hanley and Mr. Pitt, the very picture of taste and sober elegance. Shallow in the chest, Grey thought uncharitably—though the suit of puce superfine was beautifully tailored to flatter the man’s slenderness. Spindle-shanked, too; Trevelyan shifted weight, and a shadow winked on his left leg, where the pad of the downy-calf he wore had shifted under a clocked silk stocking.

Lord John turned the posy critically in his hand, as though inspecting it for wilt, watching the man from beneath lowered lashes. He knew well enough how to look without appearing to do so. He wished he were not in the habit of such surreptitious inspection—if not, he wouldn’t now be facing this dilemma.

The discovery that an acquaintance suffered from the French disease would normally be grounds for nothing more than distaste at worst, disinterested sympathy at best—along with a heartfelt gratitude that one was not oneself so afflicted. Unfortunately, the Honorable Joseph Trevelyan was not merely a club acquaintance; he was betrothed to Grey’s cousin.

The steward murmured something at his elbow; by reflex, he handed the posy to the man and flicked a hand in dismissal.

“No, I shan’t dine yet. Colonel Quarry will be joining me.”

“Very good, my lord.”

Trevelyan had rejoined his companions at a table across the room, his narrow face flushed with laughter at some jest by Pitt.

Grey couldn’t stand there glowering at the man; he hesitated, unsure whether to go across to the smoking room to wait for Quarry, or perhaps down the hall to the library. In the event, though, he was prevented by the sudden entry of Malcolm Stubbs, lieutenant of his own regiment, who hailed him with pleased surprise.

“Major Grey! What brings you here, eh? Thought you was quite the fixture at White’s. Got tired of the politicals, have you?”

Stubbs was aptly named, no taller than Grey himself, but roughly twice as wide, with a broad cherubic face, wide blue eyes, and a breezy manner that endeared him to his troops, if not always to his senior officers.

“Hallo, Stubbs.” Grey smiled, despite his inner disquiet. Stubbs was a casual friend, though their paths seldom crossed outside of regimental business. “No, you confuse me with my brother Hal. I leave the whiggery-pokery up to him.”

Stubbs went pink in the face, and made small snorting noises.

“Whiggery-pokery! Oh, that’s ripe, Grey, very ripe. Must remember to tell it to the Old One.” The Old One was Stubbs’s father, a minor baronet with distinct whiggish leanings, and likely a familiar of both White’s Club and Lord John’s brother.

“So, you a member here, Grey? Or a guest, like me?” Stubbs, recovering from his attack of mirth, waved a hand round the spacious confines of the white-naped dining room, casting an admiring glance at the impressive array of decanters being arranged by the steward at a sideboard.

“Member.”

Trevelyan was nodding cordially to the Duke of Gloucester, who returned the salutation. Christ, Trevelyan really did know everyone. With a small effort, Grey returned his attention to Stubbs.

“My godfather enrolled me for the Beefsteak at my birth. Starting at the age of seven, which is when he assumed reason began, he brought me here every Wednesday for luncheon. Got out of the habit while abroad, of course, but I find myself coming back, whenever I’m in Town.”

The wine steward was leaning down to offer Trevelyan a decanter of port; Grey recognized the embossed gold tag at its neck—San Isidro, a hundred guineas the cask. Rich, well-connected . . . and infected. Damn, what was he going to do about this?

“Your host not here yet?” He touched Stubbs’s elbow, turning him toward the door. “Come, then—let’s have a quick one in the library.”

They strolled down the pleasantly shabby carpet that lined the hall, chatting inconsequently.

“Why the fancy-dress?” Grey asked casually, flicking at the braid on Stubbs’s shoulder. The Beefsteak wasn’t a soldier’s haunt; though a few officers of the regiment were members, they seldom wore full dress uniform here, save when on their way to some official business. Grey himself was only uniformed because he was meeting Quarry, who never wore anything else in public.

“Got to do a widow’s walk later,” Stubbs replied, looking resigned. “No time to go back for a change.”

“Oh? Who’s dead?” A widow’s walk was an official visit, paid to the family of a recently deceased member of the regiment, to offer condolences and make inquiry as to the widow’s welfare. In the case of an enlisted man, such a visit might include the handing over of a small amount of cash contributed by the man’s intimates and immediate superiors—with luck, enough to bury him decently.

“Timothy O’Connell.”

“Really? What happened?” O’Connell was a middle-aged Irishman, surly but competent; a lifelong soldier who had risen to sergeant by dint of his ability to terrify subordinates—an ability Grey had envied as a seventeen-year-old subaltern, and still respected ten years later.

“Killed in a street brawl, night before last.”

Grey’s brows went up at that. “Must have been set on by a mob,” he said, “or taken by surprise; I’d have given long odds on O’Connell in a fight that was even halfway fair.”

“Didn’t hear any details; I’m meant to ask the widow.”

Taking a seat in one of the Beefsteak’s ancient but comfortable library wing chairs, Grey beckoned to one of the servants.

“Brandy—you, too, Stubbs? Yes, two brandies, if you please. And tell someone to fetch me when Colonel Quarry comes in, will you?”

“Thanks, old fellow; come round to my club and have one on me next time.” Stubbs unbuckled his dress sword and handed it to the hovering servant before making himself comfortable in turn.

“Met your cousin the other day, by the bye,” he remarked, wriggling his substantial buttocks deeply into the chair. “Out ridin’ in the Row—handsome girl. Nice seat,” he added judiciously.

“Indeed. Which cousin would that be?” Grey asked, with a small sinking feeling. He had several female cousins, but only two whom Stubbs might conceivably admire, and the way this day was going . . .

“The Pearsall girl,” Stubbs said cheerfully, confirming Grey’s presentiment. “Olivia? That the name? I say, isn’t she engaged to that chap Trevelyan? Thought I saw him just now in the dining room.”

“You did,” Grey said shortly, not anxious to speak about the Honorable Joseph at the moment. Once started on a conversational gambit, though, Stubbs was as difficult to deflect from his course as a twenty-pounder on a downhill slope, and Grey was obliged to hear a great deal regarding Trevelyan’s activities and social prominence—things of which he was only too well aware.

“Any news from India?” he asked finally, in desperation.

This gambit worked; most of London was aware that Robert Clive was snapping at the Nawab of Bengal’s heels, but Stubbs had a brother in the 46th Foot, presently besieging Calcutta with Clive, and was thus in a position to share any number of grisly details that had not yet made the pages of the newspaper.

“. . . so many British prisoners packed into the space, my brother said, that when they dropped from the heat, there was no place to put the bodies; those left alive were obliged to trample on the fallen underfoot. He said”—Stubbs looked round, lowering his voice slightly—“some poor chaps had gone mad from the thirst. Drank the blood. When one of the fellows died, I mean. They’d slit the throat, the wrists, drain the body, then let it fall. Bryce said they could scarce put a name to half the dead when they pulled them out of that place, and—”

“Think we’re bound there, too?” Grey interrupted, draining his glass and beckoning for another pair of drinks, in the faint hope of preserving some vestige of his appetite for luncheon.

“Dunno. Maybe—though I heard a bit of gossip last week, sounded rather as though it might be the Americas.” Stubbs shook his head, frowning. “Can’t say as there’s much to choose between a Hindoo and a Mohawk—howling brutes, the lot—but there’s the hell of a lot better chance of distinguishing oneself in India, you ask me.”

“If you survive the heat, the insects, the poisonous serpents, and the dysentery, yes,” Grey said. He closed his eyes in momentary bliss, savoring the balmy touch of English June that drifted through the open window.

Speculation was rampant and rumors rife as to the regiment’s next posting. France, India, the American Colonies . . . perhaps one of the German states, Prague on the Russian front, or even the West Indies. Great Britain was battling France for supremacy on three continents, and life was good for a soldier.

They passed an amiable quarter hour in such idle conjectures, during which Grey’s mind was free to return to the difficulties posed by his inconvenient discovery. In the normal course of things, Trevelyan would be Hal’s problem to deal with. But his elder brother was abroad at the moment, in France and unreachable, which left Grey as the man on the spot. The marriage between Trevelyan and Olivia Pearsall was set to take place in six weeks’ time; something would have to be done, and done quickly.

Perhaps he had better consult Paul or Edgar—but neither of his half-brothers moved in society; Paul rusticated on his estate in Sussex, barely moving a foot as far as the nearest market town. As for Edgar . . . no, Edgar would not be helpful. His notion of dealing discreetly with the matter would be to horsewhip Trevelyan on the steps of Westminster.

The appearance of a steward at the door, announcing the arrival of Colonel Quarry, put a temporary end to his distractions.

Rising, he touched Stubbs’s shoulder.

“Fetch me after dinner, will you?” he said. “I’ll come along on your widow’s walk, if you like. O’Connell was a good soldier.”

“Oh, will you? That’s sporting, Grey; thanks.” Stubbs looked grateful; offering condolences to the bereaved was not his strong suit.

Trevelyan had fortunately concluded his meal and departed; the stewards were sweeping crumbs off the vacant table as Grey entered the dining room. Just as well; it would have curdled his stomach if he were obliged to look at the man while eating.

He greeted Harry Quarry cordially, and forced himself to make conversation over the soup course, though his mind was still preoccupied. Ought he to seek Harry’s counsel in the matter? He hesitated, dipping his spoon. Quarry was bluff and frequently uncouth in manner, but he was a shrewd judge of character and more than knowledgeable in the messier sort of human affairs. He was of good family and knew how the world of society worked. Above all, he could be trusted to keep a confidence.

Well, then. Talking over the matter might at least clarify the situation in his own mind. He swallowed the last mouthful of broth and set down his spoon.

“Do you know Joseph Trevelyan?”

“The Honorable Mr. Trevelyan? Father a baronet, brother in Parliament, a fortune in Cornish tin, up to his eyeballs in the East India Company?” Harry raised his brows in irony. “Only to look at. Why?”

“He is engaged to marry my young cousin, Olivia Pearsall. I . . . merely wondered whether you had heard anything regarding his character.”

“Bit late to be makin’ that sort of inquiry, ain’t it, if they’re already betrothed?” Quarry spooned up a bit of unidentifiable vegetation from his soup bowl, eyed it critically, then shrugged and swallowed it. “Not your business anyway, is it? Surely her father’s satisfied.”

“She has no father. Nor mother. She is an orphan, and has been my brother Hal’s ward these past ten years. She lives in my mother’s household.”

“Mm? Oh. Didn’t know that.” Quarry chewed bread slowly, thick brows lowered thoughtfully as he looked at his friend. “What’s he done? Trevelyan, I mean, not your brother.”

Lord John raised his own brows, toying with his soup spoon.

“Nothing, to my knowledge. Why ought he to have done anything?”

“If he hadn’t, you wouldn’t be inquiring as to his character,” Quarry pointed out logically. “Out with it, Johnny; what’s he done?”

“Not so much what he’s done, as the result of it.” Lord John sat back, waiting until the steward had cleared away the course and retreated out of earshot. He leaned forward a little, lowering his voice well past the point of discretion, yet feeling the blood rise in his cheeks nonetheless.

It was absurd, he told himself. Any man might casually glance—but his own predilections rendered him more than delicate in such a situation; he could not bear the notion that anyone might suspect him of deliberate inspection. Not even Quarry—who, finding himself in a similarly accidental situation, would likely have seized Trevelyan by the offending member and loudly demanded to know the meaning of this.

“I . . . happened to retire for a moment, earlier”—he nodded toward the Chinese screen—“and came upon Trevelyan, unexpectedly. I . . . ah . . . caught sight—” Christ, he was blushing like a girl; Quarry was grinning at his discomfiture.

“. . . think it is pox,” he finished, his voice barely a murmur.

The grin vanished abruptly from Quarry’s face, and he glanced at the Chinese screen, from behind which Lord Dewhurst and a friend were presently emerging, deep in conversation. Catching Quarry’s gaze upon him, Dewhurst glanced down automatically, to be sure his flies were buttoned. Finding them secure, he glowered at Quarry and turned away toward his table.

“Pox.” Quarry pitched his own voice low, but still a good deal louder than Grey would have liked. “You mean the syphilis?”

“I do.”

“Sure you weren’t seeing things? I mean, glimpse from the corner of the eye, bit of shadow . . . easy to make a mistake, eh?”

“I shouldn’t think so,” Grey said tersely. At the same time, his mind grasped hopefully at the possibility. It hadbeen only a glimpse. Perhaps he could be mistaken. . . . It was a very tempting thought.

Quarry glanced at the Chinese screen again. The windows were all open to the air, and the glorious June sunshine was streaming through them in floods. The air was like crystal; Grey could see individual grains of salt against the linen cloth, where he had upset the saltcellar in his agitation.

“Ah,” Quarry said. He fell silent for a moment, tracing a pattern with one forefinger in the spilled salt.

He didn’t ask whether Grey would recognize a chancrous sore. Any young serving officer must now and then have been obliged to accompany the surgeon inspecting troops, to take note of any man so diseased as to require discharge. The variety of shapes and sizes—to say nothing of conditions—displayed on such occasions was common fodder for hilarity in the officers’ mess on the evening following inspections.

“Well, where does he go whoring?” Quarry asked, looking up and rubbing salt from his finger.

“What?” Grey looked at him blankly.

Quarry raised one thick brow.

“Trevelyan. If he’s poxed, he caught it somewhere, didn’t he?”

“I daresay.”

“Well, then.” Quarry sat back in his chair, pleased.

“He needn’t have caught it in a brothel,” Grey pointed out. “Though I admit it’s the most likely place. What difference does it make?”

Quarry raised both brows.

“The first thing is make certain of it, eh, before you stink up the whole of London with a public accusation. I take it you don’t want to make overtures to the man yourself, in order to get a better look.”

Quarry grinned widely, and Grey felt the blood rise in his chest, washing hot up his neck. “No,” he said shortly. Then he collected himself and lounged back a little in his chair. “Not my sort,” he drawled, flicking imaginary snuff from his ruffle.

Quarry guffawed, his own face flushed with a mixture of claret and amusement. He hiccuped, chortled again, and slapped both hands down on the table.

“Well, whores ain’t so picky. And if a moggy will sell her body, she’ll sell anything else she has—including information about her customers.”

Grey stared blankly at the Colonel. Then the suggestion dropped into focus.

“You are suggesting that I employ a prostitute to verify my impressions?”

“You’re quick, Grey, damn quick.” Quarry nodded approval, snapping his fingers for more wine. “I was thinking more of finding a girl who’d seen his prick already, but your way’s a long sight easier. All you’ve got to do is invite Trevelyan along to your favorite convent, slip the lady abbess a word—and a few quid—and there you are!”

“But I—” Grey stopped himself short of admitting that far from patronizing a favored bawdery, he hadn’t been in such an establishment in several years. He had successfully suppressed the memory of the last such experience; he couldn’t say now even which street the building had been in.

“It’ll work a treat,” Quarry assured him, ignoring his discomposure. “Not likely to be too dear, either; two pound would probably do it, three at most.”

“But once I know whether my suspicion is confirmed—”

“Well, if he ain’t poxed, there’s no difficulty, and if he is . . .” Quarry squinted in thought. “Hmm. Well, how’s this? If you was to arrange for the whore to screech and carry on a bit, once she’d got a good look at him, then you rush out of your own girl’s chamber, so as to see what’s the matter, eh? House might be afire, after all.” He chortled briefly, envisioning the scene, then returned to the plan.

“Then, if you’ve caught him with his breeches down, so to speak, and the situation revealed beyond doubt, I shouldn’t think he’d have much choice save to find grounds for breaking the engagement himself. What d’ye say to that?”

“I suppose it might work,” Grey said slowly, trying to picture the scene Quarry painted. Given a whore of sufficient histrionic talent . . . and there would be no need for Grey actually to utilize the brothel’s services personally, after all.

The wine arrived, and both men fell momentarily silent as it was poured. As the steward departed, though, Quarry leaned across the table, eyes alight.

“Let me know when you mean to go; I’ll come along for the sport!”

Chapter 2

Widow’s Walk

France,” Stubbs was saying in disgust, pushing his way through the crowd in Clare Market. “Bloody France again, can you believe it? I dined with DeVries, and he told me he’d had it direct from old Willie Howard. Guarding the shipyards in frigging Calais, likely!”

“Likely,” Grey repeated, sidling past a fishmonger’s barrow. “When, do you know?” He aped Stubbs’s annoyance at the thought of a possibly humdrum French posting, but in fact, this was welcome news.

He was no more immune to the lure of adventure than any other soldier, and would enjoy to see the exotic sights of India. However, he was also well aware that such a foreign posting would likely keep him away from England for two years or more—away from Helwater.

A posting in Calais or Rouen, though . . . he could return every few months without much difficulty, fulfilling the promise he had made to his Jacobite prisoner—a man who doubtless would be pleased never to see him again.

He shoved that thought resolutely aside. They had not parted on good terms—well, on any. But he had hopes in the power of time to heal the breach. At least Jamie Fraser was safe; decently fed and sheltered, and in a position where he had what freedom his parole allowed. Grey took comfort in the imagined vision—a long-legged man striding over the high fells of the Lake District, face turned up toward sun and scudding cloud, wind blowing through the richness of his auburn hair, plastering shirt and breeches tight against a lean, hard body.

“Hoy! This way!” A shout from Stubbs pulled him rudely from his thoughts, to find the Lieutenant behind him, gesturing impatiently down a side street. “Wherever is your mind today, Major?”

“Just thinking of the new posting.” Grey stepped over a drowsy, moth-eaten bitch, stretched out across his way and equally oblivious both to his passage and to the scrabble of puppies tugging at her dugs. “If it isFrance, at least the wine will be decent.”

O’Connell’s widow dwelt in rooms above an apothecary’s shop in Brewster’s Alley, where the buildings faced each other across a space so narrow that the summer sunshine failed to penetrate to ground level. Stubbs and Grey walked in clammy shadow, kicking away bits of rubbish deemed too decrepit to be of use to the denizens of the place.

Grey followed Stubbs through the shop’s narrow door, beneath a sign reading F. SCANLON, APOTHECARY, in faded script. He paused to stamp his foot in order to dislodge a strand of rotting vegetation that had slimed itself across his boot, but looked up at the sound of a voice from the shadows near the back of the shop.

“Good day to ye, gentlemen.” The voice was soft, with a strong Irish accent.

“Mr. Scanlon?”

Grey blinked in the gloom, and made out the proprietor, a dark, burly man hovering spiderlike over his counter, arms outspread as though ready to snatch up any bit of merchandise required upon the moment.

“Finbar Scanlon, the same.” The man inclined his head courteously. “What might I have the pleasure to be doin’ for ye, sirs, may I ask?”

“Mrs. O’Connell,” Stubbs said briefly, jerking a thumb upward as he headed for the back of the shop, not waiting on an invitation.

“Ah, herself is away just now,” the apothecary said, sidling quickly out from behind the counter in order to block the way. Behind him, a faded curtain of striped linen swayed in the breeze from the door, presumably concealing a staircase to the upper premises.

“Gone where?” Grey asked sharply. “Will she return?”

“Oh, aye. She’s gone round for to speak to the priest about the funeral. Ye’ll know of her loss, I suppose?” Scanlon’s eyes flicked from one officer to the other, gauging their purpose.

“Of course,” Stubbs said shortly, annoyed at Mrs. O’Connell’s absence. He had no wish to prolong their errand. “That’s why we’ve come. Will she be back soon?”

“Oh, I couldn’t be saying as to that, sir. Might take some time.” The man stepped out into the light from the door. Middle-aged, Grey saw, with silver threads in his neatly tied hair, but well-built, and with an attractive, clean-shaven face and dark eyes.

“Might I be of some help, sir? If ye’ve condolences for the widow, I should be happy to deliver them.” The man gave Stubbs a look of straightforward openness—but Grey saw the tinge of speculation in it.

“No,” he said, forestalling Stubbs’s reply. “We’ll wait in her rooms for her.” He turned toward the striped curtain, but the apothecary’s hand gripped his arm, halting him.

“Will ye not take a drink, gentlemen, to cheer your wait? ’Tis the least I can offer, in respect of the departed.” The Irishman gestured invitingly toward the cluttered shelves behind his counter, where several bottles of spirit stood among the pots and jars of the apothecary’s stock.

“Hmm.” Stubbs rubbed his knuckles across his mouth, eyes on the bottle. “It wasrather a long walk.”

It had been, and Grey, too, accepted the offered drink, though with some reluctance, seeing Scanlon’s long fingers nimbly selecting an assortment of empty jars and tins to serve as drinking vessels.

“Tim O’Connell,” Scanlon said, lifting his own tin, whose label showed a drawing of a woman swooning on a chaise longue. “The finest soldier who ever raised a musket and shot a Frenchman dead. May he rest in peace!”

“Tim O’Connell,” Grey and Stubbs muttered in unison, lifting their jars in brief acknowledgment.

Grey turned slightly as he brought the jar to his lips, so that the light from the door illuminated the liquid within. There was a strong smell from whatever had previously filled the jar—anise? camphor?—overlaying the smell of alcohol, but there were no suspicious crumbs floating in it, at least.

“Where was Sergeant O’Connell killed, do you know?” Grey asked, lowering his makeshift cup after a small sip, and clearing his throat. The liquid seemed to be straight grain alcohol, clear and tasteless, but potent. His palate and nasal passages felt as though they had been seared.

Scanlon swallowed, coughed, and blinked, eyes watering—presumably from the liquor, rather than emotion—then shook his head.

“Somewhere near the river, is all I heard. The constable who came to bring the news said he was bashed about somethin’ shocking, though. Knocked on the head in some class of a tavern fight and then trampled in the scrum, perhaps. The constable did mention that there was a heelprint on his forehead, God have mercy on the poor man.”

“No one arrested?” Stubbs wheezed, face going red with the strain of not coughing.

“No, sir. As I understand the matter, the body was found lyin’ half in the water, on the steps by Puddle Dock. Like enough, the tavern owner it was who dragged him out and dumped him, not wantin’ the nuisance of a corpse on his premises.”

“Likely,” Grey echoed. “So no one knows precisely where or how the death occurred?”

The apothecary shook his head solemnly, picking up the bottle.

“No, sir. But then, none of us knows where or when we shall die, do we? The only surety of it is that we shall all one day depart this world, and heaven grant we may be welcome in the next. A drop more, gentlemen?”

Stubbs accepted, settling himself comfortably onto a proffered stool, one booted foot propped against the counter. Grey declined, and strolled casually round the shop, cup in hand, idly inspecting the stock while the other two lapsed into cordial conversation.

The shop appeared to do a roaring business in aids to virility, prophylactics against pregnancy, and remedies for the drip, the clap, and other hazards of sexual congress. Grey deduced the presence of a brothel in the near neighborhood, and was oppressed anew at the thought of the Honorable Joseph Trevelyan, whose existence he had momentarily succeeded in forgetting.

“Those can be supplied with ribbons in regimental colors, sir,” Scanlon called, seeing him pause before a jaunty assortment of Condoms Design’d for Gentlemen,each sample displayed on a glass mold, the ribbons that secured the neck of each device coiled delicately around the foot of its mold. “Sheep’s gut or goat, per your preference, sir—scented, three farthings extra. That would be gratis to you gentlemen, of course,” he added urbanely, bowing as he tilted the neck of the bottle over Stubbs’s cup again.

“Thank you,” Grey said politely. “Perhaps later.” He scarcely noticed what he was saying, his attention caught by a row of stoppered bottles.

Mercuric Sulphide,read the labels on several, and Guiacumon others. The contents appeared to differ in appearance, but the descriptive wording was the same for both:

For swift and efficacious treatment of the gonorrhoea,

soft shanker, syphilis, and all other forms of venereal pox.

For a moment, he had the wild thought of inviting Trevelyan to dinner, and introducing one of these promising substances into his food. Unfortunately, he had too much experience to put any trust in such remedies; a dear friend, Peter Tewkes, had died the year before, after undergoing a mercuric “salivation” for the treatment of syphilis at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital, after several attempts at patent remedy had failed.

Grey had not witnessed the process personally, having been exiled in Scotland at the time, but had heard from mutual friends who had visited Tewkes, and who had talked feelingly of the vile effects of mercury, whether applied within or without.

He couldn’t allow Olivia to marry Trevelyan if he was indeed afflicted; still, he had no desire to be arrested himself for attempted poisoning of the man.

Stubbs, always gregarious, was allowing himself to be drawn into a discussion of the Indian campaign; the papers had carried news of Clive’s advance toward Calcutta, and the whole of London was buzzing with excitement.

“Aye, and isn’t one of me cousins with Himself?” the apothecary was saying, drawing himself up with evident pride. “The Eighty-first, and no finer class of soldiers to be found on God’s green earth”—he grinned, flashing good teeth—“savin’ your presences, sirs, to be sure.”

“Eighty-first?” Stubbs said, looking puzzled. “Thought you said your cousin was with the Sixty-third.”

“Both, sir, bless you. I’ve several cousins, and the family runs to soldiers.”

His attention thus returned to the apothecary, Grey slowly became aware that something was slightly wrong about the man. He strolled closer, eyeing Scanlon covertly over the rim of his cup. The man was nervous—why? His hands were steady as he poured the liquor, but there were lines of strain around his eyes, and his jaw was set in a way quite at odds with his stream of casual talk. The day was warm, but it was not so warm in the shop as to justify the slick of sweat at the apothecary’s temples.