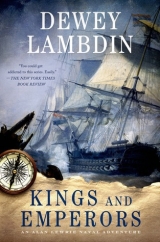

Текст книги "Kings and Emperors"

Автор книги: Dewey Lambdin

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 8 (всего у книги 26 страниц)

“Aye, we are requested to return to harbour, Mister Westcott,” Lewrie told him. “The note does not say why, but I am to attend the General at my earliest opportunity. Shape course for the Rock, sir, and crack on sail.”

“Aye aye, sir!” Westcott happily agreed, and as he bawled out his orders to make more sail and alter course, the on-watch hands raised a small cheer that they would soon be back among the taverns and brothels of Gibraltar Town. Getting there would take hours, for the East-set current was dead against the course, making entrance to the Mediterranean easy, but an exit to the Atlantic a long trial. If the winds were light, an all-day’s sail could result in a progess measured in a few miles.

“You have the deck, sir,” Lewrie told Westcott. “There’s my breakfast to finish, and, I s’pose I’ll have t’dress up for the occasion.”

“Might shave close, too, sir,” Westcott said with a grin.

“Pettus! Jessop!” Lewrie shouted as he re-entered his cabins. “Heat an iron for the sash, pin the bloody star on my best coat, and black my bloody boots!”

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

Lewrie found the usually quiet Convent headquarters building a bee-hive of activity, with junior officer clerks moving between various offices with more despatch, boot or shoe heels clacking on the old stone flags or tiles. There were Colonels, Lieutenant-Colonels, and regimental Majors present, gathered in small groups, mostly with their own sort, recognisable by the detailing and colours of their uniform coats’ lapel facings and their button-hole lace. Officers turned their heads to peer at him as he approached Dalrymple’s office, muttering among themselves.

“The Navy’s here,” he heard one Colonel bray. “That means we’re going somewhere, haw haw!”

Lewrie announced himself to yet another junior Lieutenant of Foot in the anteroom, and the young fellow made a chequemark on his list. “You are to go right in, sir,” the fellow told him. “You are expected.”

Lewrie entered the offices and left his cocked hat on a side table where there were already several ornately laced and feathered Army officer’s bicornes, and one civilian hat.

“Ah, Sir Alan,” General Dalrymple said in greeting, waving him to come forward. “Do allow me to name to you General Sir Brent Spencer; Sir Brent, this is Captain Sir Alan Lewrie, Baronet, Captain of HMS Sapphire.”

“Pleased to make your acquaintance, sir,” Lewrie and Spencer said almost as one, and offering their hands briefly.

“Mister Thomas Mountjoy of the Foreign Office, you already know,” Sir Hew went on. “It is his news that prompted this meeting. Do inform us of what you have heard, or learned of, Mister Mountjoy.”

“Gladly, Sir Hew,” Mountjoy said, springing from a chair with alacrity. He was beaming fit to bust. “I have gotten a report from a source in Madrid that, on Dos de Mayo, the second of this month, the people of the city rose up en masse against the French, hunting down and killing every off-duty Frenchman they could find, arming themselves as best they were able, and slaughtering them. Marshal Murat turned out his troops and resorted to using artillery against the mobs. The riots were put down after three hours’ fighting, then the French had a riot of their own, entering every building in sight and dragging suspected rioters out to be shot or bayonetted. It was a great slaughter, ’mongst the guilty and the innocent, and atrocious crimes were committed … looting, theft, rape, and pillage on a grand scale, much like what happens when an army breaks into a walled town that resisted a long siege, in mediaeval times. A day later, one other of my sources relates that the garrison troops and the Spanish Navy at Cartagena arose, as well, and that there is great unrest in Seville. I have so far un-substantiated reports that many cities in the North, in Galicia and Catalonia, are also restive.”

“For real, Mountjoy?” Lewrie had to ask, wondering if the riots were invented to spur Dalrymple into some rash action, on a par with the false reports of atrocities that Mountjoy had spun out of thin air.

“For real, Captain Lewrie,” Mountjoy stressed. “The Spanish heard that their old kings had been arrested after they met Napoleon over the border at Bayonne, and that King Ferdinand was being forced to abdicate in favour of a king of Napoleon’s choice, one of his kin, or one of his favourite Marshals.”

“Upon that head, I have heard from General Castaños,” Sir Hew Dalrymple imparted to them all. “There is a rebellious committee forming at Seville, what the Devil do they call it, Mister Mountjoy?”

“A junta, sir,” Mountjoy supplied.

“Yes, a junta,” Dalrymple continued, “which had been pressing General Castaños to declare for them, and raise a general rebellion in Western Andalusia. Castaños has already written me for British aid should he decide to act. He has raised the idea of evacuating the fortress of Ceuta, and adding those troops, and some of the fortress’s lighter cannon to his artillery train, as well.”

“By Jove, that’d be grand!” General Spencer exclaimed. “What’s stopping him, then?”

“That would be the other largest force of Spanish troops in Cádiz, Sir Brent,” Mountjoy told him, dashing cold water on Spencer’s enthusiasm. “The governor of Cádiz is decidely pro-French, and, with the French warships that escaped into port after Trafalgar to count on to defend him, he could put down any rebellion.”

“They can’t get to sea, with Admiral Purvis watchin’ them,” Lewrie supplied, “but they could add their gunfire to defeat any attempt to take Cádiz … or bombard the city if the citizens arose against the governor. Their crews could hold the port’s forts if the troops at Cádiz march on Castaños if he does join the junta.”

“You have no news from that quarter, Mister Mountjoy?” Sir Hew asked.

“A tough nut to crack, sir, sorry to say,” Mountjoy said with a frown, and a shake of his head. “I’ve had no luck at getting an … a source in. Not for long.”

“A spy, you’re saying?” General Spencer barked as if someone had just cursed him. “That your line of work, is it, sir?”

“Someone must gather intelligence for military operations,” Lewrie said, defending him. “Else, you swan off into terra incognita, deaf, dumb, blind, and get your … fundaments kicked.”

“Much of a piece with cavalry videttes making scouts, and gallopers to bring news of enemy movements,” Sir Hew grudgingly allowed. “Regrettably necessary, at times. General Castaños informs me that he is also short of arms to give to volunteers whom he expects to come forward once the junta in Seville declares. I have on hand in the armouries at least one thousand muskets, with bayonets, cartridge pouches, and accoutrements, and I think I may spare about sixty thousand pre-made cartridges for that purpose, and shall write London to ask for more, at once. If the Spanish wish to send ships to Ceuta, we will allow them to do so.”

“And I finally get the fortress, without a long siege, ah hah!” General Spencer cried, clapping his hands in delight. He’d spent long months, cooling his heels, once it was realised that Ceuta had been re-enforced, and could not be taken without a larger army.

“Oh, I fear not, Sir Brent,” Dalrymple said with the faintest of smiles on his face. “In light of these new developments, I think that your brigade-sized force would be of more use nearer to Cádiz. That part of your original force, which was sent on to Sicily earlier, I shall recall to join you after you’ve made a lodgement. To encourage the junta, and General Castaños.”

“Ehm … make a lodgement exactly where, Sir Hew?” Spencer asked in sudden shock at a new, even more dangerous, assignment.

“Well, so long as the forts are in the hands of the pro-French governor, it would have to be somewhere near Cádiz proper,” Mountjoy declared, then turned to Lewrie and raised a brow to prompt him.

“Anyone have a sea chart?” Lewrie asked.

General Dalrymple did not, but an aide-de-camp managed to turn up a map of the city and its environs, after a frantic search.

“Hmm, there’s this little port of Rota, though that’s a bit far from the city,” Lewrie opined after a long perusal. “Closer into the area, there’s Puerto de Santa María, on the North side of the bay.”

“Captain Lewrie became very efficient at landing and recovering troops along the coast last Summer,” Sir Hew said. “If you choose to land near Cádiz, he’s your man.”

“Well, we only put three companies ashore at one time, sir, for quick raids,” Lewrie had to qualify, “without packs or camp gear, rations and ammunition, and no artillery, no horses. If you have to depend on your transports’ crews to row your men in, it’ll take forever, they’re so thinly manned, and the number of boats will be limited. How many troops do you have, sir?”

“At present, just a bit over three thousand,” Spencer said, “a little over one brigade. Daunting. Have the French sent one of their armies to Cádiz?”

“General Castaños tells me that there is a French brigade in the city, under a Brigadier Avril,” Dalrymple said. “So far, at least, the French have left San Roque and Algeciras alone.”

“You could not enter Cádiz itself, sir,” Mountjoy warned them, “even if the Spanish juntas were suddenly in charge. They would not allow a ‘second’ Gibraltar under British rule. Their touchy Spanish pride is too great for that.”

“I will send for transports, and obtain an escort from Admiral Purvis, now blockading Cádiz,” Dalrymple declared. “Boats from those warships, manned by British sailors, will speed the landings, at whichever place you decide, Sir Brent.”

“Or, where the Spanish let you,” Mountjoy cautioned again.

“We have some idle transports in port, already, troopers, and supply ships,” Dalrymple said. “Captain Lewrie, you and your ship will go along as part of the escort. Depending upon whom Purvis sends me, you may be senior in command of the escort, and the co-ordination.”

“I was wondering why I was summoned, sir. Aye,” Lewrie said, grinning. “Happy to oblige.”

“Then let us have a drink, to seal the bargain, as it were,” Dalrymple happily proposed.

Well, that’s one way t’end my bordeom, Lewrie thought as wine and glasses were fetched; but if I get pressed into Admiral Purvis’s fleet, will I ever see Gibraltar again, or Maddalena?

At least it would beat the sight of Ceuta, or hauling cattle from Tetuán, all hollow.

BOOK TWO

Therefore let every man now task his thought

That this fair action may on foot be brought.

–WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE, THE LIFE OF HENRY THE FIFTH, (ACT I, SCENE II, 309–310)

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

“Should we hoist a broad pendant and name you a Commodore, sir?” Lt. Westcott proposed, craning his neck to look aloft. “Even if it’d be the lesser sort—”

“An Army general gave the orders, and he don’t count,” Lewrie countered, looking upwards himself. “No, I may command the escorting force … such as it is … but Admiralty’d never stand for it. I’ll stand on as I am.”

He lowered his gaze to the clutch of troop ships and supply vessels that wallowed along in passably decent order astern of his two-decker. All that could be scraped up at short notice to protect the convoy was a 32-gun frigate, a Sixth Rate sloop of war mounting but twenty light guns, and two brig-sloops. Lewrie knew that the French warships left over from the Battle of Trafalgar, now closely blockaded in Cádiz, would never come out to harm his charges, but there were still rumours that a large squadron of French ships at Rochefort, and some frigates in the mouth of the Gironde River near Bordeaux, could sortie at any time. Those rumours kept him up at night, and he secretly hoped that he could get General Spencer’s troops ashore, and the merchant ships away, without opposition, so they would no longer be his responsibility.

“Damn these perverse winds, and the currents!” he spat.

Since leaving Gibraltar on the fourteenth of May, and rounding Pigeon Island into the Strait, they had proceeded at a slug’s pace, hobbled by the in-rushing current into the Mediterranean. Sailing “full and by” hard on the wind for several days might seem swift and bracing, but that was an illusion, for their overall speed over the ground resulted in only a few miles per hour. The convoy’s first leg, a long board Sou’west, only got them a few miles West of Parsley Island before they had to tack and cross the Strait to halfway ’twixt Pigeon Island and Tarifa. The second tack Sou’west had fetched them close to the Moroccan city of Alcazar, and the third had gotten them five miles East of Tarifa.

And so it had gone from there, day after day. Lewrie led the convoy out West-Sou’west to get clear of the current, taking advantage of a wind shift, far enough out off the coast of Morocco that a simple turn North would bring the convoy into contact with Admiral John Childs Purvis’s blockading ships off Cádiz. Another shift of winds had put a stop to that simple run, that combined with a bout of foul weather, and they all had short-tacked under reduced sail through several half-gales to make their Northing. And, when the gales blew out and calmer winds and seas returned, they ran into a fringe of the Nor’east Trades, into which they butted the wrong way. The Trades were simply grand for departing Europe for the Americas or the Caribbean, but nigh a “dead muzzler” for returning.

“Land Ho!” the main mast lookout in the cross-trees shouted down. “Two points orf th’ starb’d beam!”

“Any guess as to what land?” Lewrie scoffed to his assembled watch-standers. “Mister Yelland?”

“Some part of Spain, sir,” the Sailing Master said, sounding as if he’d made a jest. “If we could send a Mid aloft with my book of the coast, I could tell you more.”

“Fetch it,” Lewrie demanded. “Mister Harvey?” he said to the nearest Midshipman. “Aloft with you and Mister Yelland’s book, and tell us what you see.”

“Aye, sir,” Harvey replied, looking eager for a scaling of the shrouds.

“Don’t drop it overside, mind, Mister Harvey,” Yelland said as he brought the book of coastal sketches from the chart toom. “Or your bottom will pay for it.”

Midshipman Harvey took the larboard shrouds, the windward side, to the cat harpings, switched over to the futtock shrouds to make his way to the main top, hanging like a spider upside down for a bit, and then up the narrower upper shrouds and rat-lines to the cross-trees, a set of narrow slats that braced the top-masts’ stays, to share that precarious perch with the lookout on duty. Harvey raised a telescope to peer landward, flipped pages in the coastal navigation sketchbook, peered some more, then shouted down. “It’s Cape Trafalgar, sir! Cape Trafalgar, fifteen miles off!”

“Very good, Mister Harvey!” Lewrie called aloft, cupping hands by his mouth. “Return to the deck, with the book.”

“Aye aye, sir!”

“We’ll stand on on this tack ’til Noon Sights, then,” Lewrie announced, “when Cape Trafalgar is truly recognised, then go about Nor’west, which’d put us somewhere off Cádiz, and in sight of our blockading squadrons sometime round dusk. Sound right, Mister Yelland?”

“If the winds hold, aye, sir,” Yelland agreed. “That’d place us, oh … round twenty-odd miles off Cádiz, and sure to run across one of our ships.”

“I s’pose I’ll have t’shave, and dress for the occasion,” Lewrie glumly said, rubbing a stubbly cheek. “Called to the flagship, all that? Mister Westcott, best you warn my boat crew t’scrub up and wash behind their ears. Best turn-out, hey?”

“Aye, sir,” Westcott responded with a faint snigger.

“I’ll be aft. Carry on, the watch,” Lewrie said, turning to go to his cabins.

“Why does the Captain dislike dressing in his finest, sir?” Lt. Elmes asked once Lewrie had departed the quarterdeck.

“It’s the sash and star of his knighthood he dislikes, Mister Elmes,” Westcott informed him in a low voice. “Officially, it was awarded for his part in a fight against a French squadron off the coast of Louisiana in 1803, but he strongly suspects that it was a cynical way for the Government to drum up support for going back to war, by publicising the fact that the French tried to murder him, and killed his wife instead, when they were in Paris during the Peace of Amiens.”

“Murdered?” Lt. Elmes gawped.

“The Captain was invited to a meeting with Napoleon at the Tuileries Palace,” Westcott explained. “He had five or six swords of dead French officers, and thought to return them to the families, in exchange for an old hanger that Napoleon took off him at Toulon in Ninety-Four, when the Captain would not give his parole and leave his men after their mortar ship was blown up and sunk. It turned to shit, he angered Napoleon somehow, and the next thing he knew, they were being chased cross Northern France to Calais.”

“He’s met the Ogre?” Elmes marvelled. “Twice? I never knew. What a tale!”

“To make matters worse, when the Captain was presented at Saint James’s Palace to be knighted, the King was having a bad day, and got confused and added Baronet,” Westcott went on, making a face. “You can imagine how it all left a sour taste in the Captain’s mouth. He earned a knighthood, and a Baronetcy, a dozen times over during his career, mind, long before I met him, and he’s done a parcel of hard fighting, since, but … that don’t signify to him. He doesn’t like to speak of it, so … don’t raise the matter with him.”

“I stand warned, Mister Westcott, though … I’d give a month’s pay to hear the whole story,” Elmes said with a wistful note to his voice.

“I’ll tell you of the fight off Louisiana,” Westcott offered. “The French were taking over Louisiana, and were rumoured to be sending a large squadron to New Orleans for the hand-over, and we were ordered to pursue and stop them if we could, just four ships, three frigates, and a sixty-four…”

* * *

Late in the afternoon, the winds dropped and the seas calmed, just after lookouts aloft spotted strange sails on the Northern horizon, quickly identified as British ships. Sapphire made her number to them once within five miles of them, and the towering First Rate flagship hoisted Captain Repair On Board. The salute to Admiral Purvis was fired off, the cutter was drawn up to the entry-port battens, and Lewrie was over the side and into his boat at once, dressed in his best, with the sash and star over his waist-coat and pinned to his coat, with his longer, slimmer presentation sword at his waist instead of his favourite, everyday, hanger.

“With luck, they’ll sport me supper, Mister Westcott. Keep things in order ’til I get back,” Lewrie shouted up in parting, and the cutter began its long row to the flagship. Another boat set out from one of the transports; General Sir Brent Spencer would attend the meeting, whether he’d been summoned or not.

It was a long climb from his boat to the quarterdeck of the flagship, past three decks of guns and a closed entry-port on its middle gun deck, one surrounded by overly ornate gilt scrollwork. He was panting, and his wounded left arm and right leg were making sore threats by the time he heaved himself in-board to the trilling Bosuns’ calls, the stamp of Marines’ boots, and the slap of hands on wooden stocks as arms were presented. He took a deep breath, made sure he was two steps inward from the lip of the entry-port, and doffed his hat in a replying salute.

“Captain Sir Alan Lewrie, Baronet, of the Sapphire, coming aboard to report to the Admiral,” Lewrie told the immaculately turned-out Lieutenant.

“If you will come this way, sir,” the officer bade, motioning towards the stern, and the Admiral’s cabins. “Ehm … who is that coming alongside, sir?”

“That’ll be General Sir Brent Spencer, who’s been sent to land near Cádiz.”

“Oh. I see, sir!”

* * *

He was announced to Admiral John Childs Purvis, though taking a moment to gawk over Purvis’s great-cabins’ spaciousness and elegant decor. He had come to think his own cabins were a tad grand, but the Admiral’s were magnificent.

“Captain Sir Alan Lewrie, Baronet, sir, of the Sapphire,” the Lieutenant said, doing the honours.

“Sir Alan,” Purvis replied, slowly rising from the desk in his day-cabin, looking worn and tired, and just a bit leery whether this un-looked-for newcomer might be yet another onerous burden to be borne. “I take it that your convoy bears General Sir Brent Spencer and his troops? I received a letter from General Dalrymple two days ago, but I had not expected the force to be assembled, yet, much less sent on. How many troops does Spencer have?”

“Nigh five thousand, sir,” Lewrie crisply replied. “Sir Hew Dalrymple added the Sixth Foot, and some artillery from Gibraltar’s garrison. There are more being ordered from Sicily, to come later. Sir Hew sent these latest appreciations for you, sir, and all the intelligence he could gather up.”

“Ah, thank you, sir,” Purvis said, sitting back down to open the thick packet and scan through them. “Do sit, Sir Alan. Wine?”

“Please, sir,” Lewrie replied.

“Hah!” the Admiral scoffed after reading through the gist of Dalrymple’s packet. “Dalrymple is rather precipitate to send along the troops so soon. Land in, or near, Cádiz? At present, the place is firmly in the hands of the French, and a pro-French lackey government. I see that he is aware of the French brigade under General Avril, though not of the division at Córdoba under a General L’Étang, who could march to re-enforce Avril rather quickly, should Spencer land.”

“Perhaps it was General Dalrymple’s intent to precipitate, to goad the Spanish into action, sir,” Lewrie suggested as his wine came. “As you can see, sir, the Spanish have already rebelled in several cities besides Madrid. Their General Castaños is almost ready to act, if he can get the garrison from Ceuta into Algeciras or Tarifa to re-enforce—”

“I am aware of those developments,” Purvis peevishly cut him off, “but Cádiz has not rebelled, and until it does—”

He was cut off, himself, by a rap on the doors to the cabins. The same Lieutenant stepped in. “Admiral, sir, General Sir Brent Spencer is come aboard, and wishes to speak with you.”

“He has, has he?” Purvis snapped, scowling heavily, then let out a much-put-upon sigh. “Very well, very well, have him come in.”

Purvis and Lewrie shot to their feet as General Spencer blew in, beaming. “Admiral Purvis!” Spencer bellowed.

“Sir Brent,” Purvis replied, rather laconically. “Wine, sir?”

“Relish a glass, thankee!” Spencer answered, coming to the desk with a glad hand out. Purvis waved both of his guests to sit, then plopped himself down behind his desk, again.

“B’lieve Sir Hew Dalrymple wrote you of our coming, and what my little army’s to do, hah?” Spencer began.

“He has, sir, but, as I was just explaining to Captain Lewrie, here, that until the situation in Cádiz changes, there is no chance of that,” Admiral Purvis declared.

“But, my men are cooped up, elbow-to-elbow, and as crop-sick as so many dogs, sir!” Spencer protested. “I must get them off those damned ships soon! If we land somewhere near Cádiz, surely the Dons would rise up and welcome us, and kick the French out!”

“Well, I will allow that I’ve gotten word from sources ashore that the city’s taken on a distinctly anti-French mood, of late,” the Admiral cautiously said, “so much so that the French consul has abandoned his residence and offices, and taken refuge aboard one of the French warships anchored in the sheltered bay behind the peninsula on which the city, and the fortifications, sit.”

“You have agents in Cádiz, sir?” Lewrie asked, amazed. “That would be welcome news to Mister Thomas Mountjoy, at Gibraltar. He’s tried to place agents inside, so far with poor results.”

“Mister Mountjoy would be one of Foreign Office’s … shadier sorts, hey?” Purvis asked with faint amusement.

“He is, sir,” Lewrie admitted.

“As I say, ’til the Spanish rise up, I fear your troops must stay aboard their transports, Sir Brent,” Admiral Purvis repeated. “And, even if they do, and declare themselves allies of Great Britain, you would not be allowed in the city, or the forts.”

“Captain Lewrie, here, mentioned some alternatives, sir,” Spencer blustered on, fidgeting where to place his ornately egret-featherd bicorne hat as a cabin steward fetched him a glass of wine. “Somewhere near Cádiz? What were they, Lewrie? Porto-something, or … started with an R?”

“Puerto de Santa María, or Rota, sir,” Lewrie supplied. “But, with the French warships, there’d be no safe way to enter the Bay of Cádiz. Same for Puerto Real, on the same bay. There’s San Fernando, South of the city, but quite close. Rota is North of the city by some eight to ten miles.”

“Oh, totally unsuitable, then,” Spencer quibbled. “But, there must be some place. God knows I’m fed up with ships, already. Even getting aboard this one, brr! Being slung up and over like a cask of salt-meat? Mean to say!”

General Spencer meant that he’d not tried to scale the battens and man-ropes, but had been hoisted aboard the flagship in a lubberly Bosun’s chair, like a cripple, or drunk. Admiral Purvis and Lewrie shared a brief smirk of amusement.

“San Fernando is near the base of the peninsula, and landing there might cut off the land route to the city,” Admiral Purvis said, “but, that would be up to the Spanish, once they do rebel, and manage to oust the French on their own. At any rate, the situation may not be my responsibility much longer. My active commission is coming to an end, and Admiralty has informed me that Admiral Cuthbert Collingwood is to relieve me on this station.”

“Admiral Collingwood, sir? I’d dearly love to meet him!” Lewrie gushed out with boyish enthusiasm.

“What, Captain Lewrie, am I not famous enough for you?” the Admiral rejoined with a peevish look.

“Oh, I didn’t mean that, sir!” Lewrie gasped. “Perish the idea! I merely meant, ehm…!”

“It is of no matter,” Purvis said, waving a hand to dismiss any thought of being insulted. “Perhaps General Dalrymple, being an Army man, has not enlightened you, Sir Brent, on Sir Alan’s adventurous accomplishments at sea. He’s reckoned as one of our most daring frigate captains, and even saddled with command of a poor older ‘fifty,’ he’s still raising devilment. The Naval Chronicle featured action reports of his doings along the Andalusian coast last Summer, which were bold.”

“You do me too much credit, sir,” Lewrie replied, putting on his modest face. “Just raising some mischief.”

Ye going t’fill Spencer in on some, or will I have t’dine him aboard and do my own braggin’? Lewrie thought.

“I dearly wish that I could have remained on-station just long enough to see Cádiz fall to us,” Purvis said with a weary sigh. “And sail in and make prize of those damned French ships that escaped us at Trafalgar.”

“That’d be grand, sir,” Lewrie told him. “Though, after anchored idle so long, they might not be in good material condition, and there’s little the Spanish yards could do to keep them up.”

“Even so, it’s more the satisfaction than the price a Prize-Court places upon them,” Purvis countered. “Claim them, and rub the Corsican Ogre’s nose in it one more time, remind Bonaparte of his worst defeat at sea, in a long string of them. Know what he is rumoured to have said when he heard about Trafalgar? ‘I cannot be everywhere,’ hah! As if that lubber would be a better Admiral than any of his!”

“Well, if he had been, sir,” Lewrie slyly replied, “we’d have bagged the lot of ’em, French and Spanish, captured ‘Boney,’ and hung him in chains at Execution Dock!”

“Hear, hear!” General Spencer crowed.

“I had planned to dine my officers in this evening,” Purvis said, as if quibbling. “If you gentlemen would care to join them?”

He sounded as if he’d rather not, but could be gracious.

“Topping!” Spencer cried. “Sure to be better than the swill I get aboard my transport, what? I accept with pleasure, sir.”

“I’d thought to return to Sapphire, sir,” Lewrie begged off, sure that that was the right thing to do. Any time with General Sir Brent Spencer was too much time, he was learning.

“Oh, if you insist, Sir Alan,” Purvis replied, much too quickly, and with a relieved grin.

“I am certain that you may regale Sir Brent,” Lewrie said.

“Oh … indeed,” Purvis said, almost pulling a face.