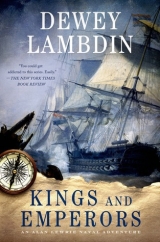

Текст книги "Kings and Emperors"

Автор книги: Dewey Lambdin

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 25 (всего у книги 26 страниц)

CHAPTER FORTY-ONE

The 17th of January dawned cold, mockingly clear, but with boisterous seas out beyond the harbour. It appeared almost too cheerful and sunny, as the day progressed, to shine so on the scene of such a dreadful and desperate battle. Upon mounting the poop deck for his first look-round with a telescope, Lewrie discovered that the number of transports huddled in Corunna’s harbour had been reduced. During the night, those ships with the sick and wounded, and the remnants of the army’s wives, children, and camp-followers, had departed.

Word had come during their supper the night before that all of the evacuated troops would not be returned to Lisbon, where they had started, but would be borne back to English ports, as if the entire expedition had been given up as a failure. That prompted speculation that the ten-thousand-man garrison left in Portugal might be withdrawn, as well. “Keep it to yourselves,” Lewrie had cautioned, though “scuttle-butt” would spread, as it usually did, to every man and boy aboard as if he had stood on the quarterdeck and bellowed the news to one and all!

Make the best of your way to English ports, is it? Lewrie reminded himself as he scanned the fleet, and gave out a derisive snort; Well, which bloody ports, hey? Regimental sick, wounded, wives, and kiddies end up at Falmouth, and their men end up at Sheerness? What idiot decided that, I wonder? England, well! It would be grand to be home for a while.

He spotted some movement among the transports anchored close to the quays at Santa Lucía; several were hauling themselves to Short Stays, and beginning to loose canvas, now full of soldiers and whatever of their weapons, gear, and rations that they could carry away. The quays and the commercial town round the village seemed to have turned red with all the regiments queued up and waiting to begin embarkation into others.

“Good morning, sir,” Lt. Westcott said, looking up from the quarterdeck. “The evacuation has begun, then?”

“Good morning, Mister Westcott,” Lewrie replied in kind. “Aye, so it appears. I think I can make out some defensive lines out beyond the town. Come on up and have a look for yourself.”

Westcott joined him and stood by the bulwarks, slowly panning his own telescope back and forth. “Looks as if they’re coming down to the quays by whole brigades. Soon as their ships are full, they’ll be off. Hmm, no sign that the French mean to have a go at them, yet.”

“No, not yet,” Lewrie glumly agreed, scanning back and forth. Bisquit came to the poop deck and sat on his haunches between them, uttering wee whines for attention. Lewrie leaned down to pet him for a bit.

“I say, sir,” Westcott said, “but is that a French flag atop Santa Lucía Hill, yonder? Our troops must have left it during the night. Yes, yes it is a French flag. Damn my eyes, I think I can make out artillery pieces!”

Lewrie straightened up and leaned onto the bulwarks with his telescope to his eye, again, straining to confirm Westcott’s observation. “Damme, you’re right. They’ve a whole battery up there, the snail-eatin’ bastards!”

As they watched, they could hear the rustling of sail-cloth, the distant rumbling of anchor cables, as more transports began to get under way, along with the approved capstan chanties allowed aboard Royal Navy warships as they, too, began to get under way to escort this clutch of ships out to sea and back to England.

“They’re opening upon our transports,” Westcott spat as they both saw the first puffs of gunpowder smoke from Santa Lucía Hill, followed seconds later by the reports of discharges, and the keens and moans of incoming roundshot.

“Aha!” Lewrie shouted as he spotted the Sailing Master, Mister Yelland, coming up from the wardroom below, still chewing on a last bite of bacon. “Mister Yelland, fetch yer sextant and come up!”

Yelland had to duck into his starboard-side sea cabin for his sextant, and a slate and chalk, before he ponderously mounted the ladderway to join them on the poop deck. “Aye, sir?” he asked.

“Where we intended to go yesterday and fire on the French if they gained the Monte Mero,” Lewrie impatiently pressed, “if we go there this morning, can we elevate our guns high enough to engage that damned Frog battery?”

For a seasoned sea-captain, Lewrie would be the last to claim that he was a dab-hand at mathematics, not like his past Sailing Masters during his career. He was forced to wait while Yelland hefted his sextant to his eye, took the measure of the hill’s height, then scribbled on his slate with many a cock of his head and some “Ah hums” thrown in for good measure. At last, he announced, “Not as deep into the inlet as you proposed yesterday, sir, no.” Yelland rubbed his un-shaven chin and allowed “If we come to anchor nearer the mid-way point ’twixt that point and the quays of Saint Lucía, about two-thirds of a mile off from the hill, would be best, and that at extreme maximum elevation of the guns.”

“Good enough, then,” Lewrie said, slamming a fist on the cap-rails of the bulwarks. “Mister Westcott, pipe All Hands to hoist the anchor and make sail. We’ll beat to Quarters once we’re under way!”

“Aye aye, sir!” Westcott said, looking positively wolf-evil as he bared his teeth in a wide, brief grin.

* * *

“Bless me, are they actually aiming at any ship?” Captain Chalmers observed from the quarterdeck of his Undaunted frigate, as French shot rumbled into the harbour waters, raising great pillars and feathers of spray and foam. “Why, they’re all over the place!”

“That will most-like change, sir,” his First Officer opined. “Cold barrels and ranging shots, what? Oops, oh my!” he added, as the French artillery scored a hit on a departing transport, splitting the ship’s main tops’l and leaving a large hole in the canvas. A second or so later, and that transport was struck, again, this hit just a bit wide of the mark and scoring down her larboard side, and raising a great cloud of dust and engrained dirt from her timbers.

“Damned plunging fire!” the Third Lieutenant exclaimed.

“I will thank you to mind your tongue, sir!” Chalmers snapped. “You know my views on curses, and blasphemy.”

“Sorry, sir.”

“There’s Sapphire getting under way, sir!” the First Officer pointed out.

“Mister Lewrie?” Captain Chalmers called out. “Has there been a signal from the flag for our group to make sail that you missed?”

“No, sir,” Midshipman Hugh Lewrie quickly answered. “The last signals to that effect showed the numbers for other ships. She is getting under way on her own, it appears, sir!”

HMS Sapphire was ringing up her best bower, even as she began to make sail; spanker, stays’ls, tops’ls, and jibs. She was turning slowly, wheeling away as if to make for the lower end of the harbour and the French battery. Undaunted was near enough to her former anchorage for everyone aboard to hear her Marine drummers beating out the Long Roll, and her fiddlers and fifers starting to play “The Bowld Soldier Boy.”

“And just what does he intend, I wonder?” Chalmers asked the aether. “Should we join him? Any signal to us?”

“That’s my grandfather’s favourite tune, sir,” Midshipman Hugh Lewrie said with a wistful note to his voice. “My father’s, too. He is going to fight!” he said with pride. “Sapphire makes no signal, sir.”

“Do you imagine, sir,” Undaunted’s First Officer asked, “that Captain Lewrie intends to draw the French battery’s fire upon his ship? She’s stouter than us. She can take their eight– and twelve-pounder shot better than we could, perhaps even the plunging fire from their howitzers.”

“Spare the transports?” Captain Chalmers wondered aloud, even as the French found the range upon another departing transport ship and scored several damaging hits. “I must say that Captain Lewrie has ‘bottom,’ in spades!”

“Yes, he does!” Midshipman Lewrie seconded that impression, if only under his breath.

* * *

“The ship is at Quarters, sir,” Lt. Westcott reported in his most formal and grave manner, then cast an eye towards the Sailing Master and his Master’s Mates, Stubbs and Dorton, all of whom were busy scribbling on their slates, their sticks of chalk squeaking in urgency between quick sights with their sextants.

“Soon, Mister Yelland?” Lewrie called to them.

“Soon, sir,” Mr. Yelland assured him, sounding anxious.

“There’s not enough room for us to go about,” Lewrie said to Lt. Westcott, waving an arm round the harbour. “We can’t stand close to the quays, wear about, and engage with the off-side battery. We would spend all our time at it. We’ll have to anchor, with the best bower and kedge, with springs on the cables.”

That drew a wince from Westcott, and a sucking of breath over his teeth. “Play target, to spare the other ships? Aye, nothing for it, then. Let go the kedge, first, and hope it finds good grounding, as rocky as the harbour is.”

“And use the best bower at a very short scope t’keep us from swinging, aye,” Lewrie grimly agreed. “Stand by to let go the kedge when Yelland decides we’re at the best place, then send topmen aloft as we free the bower.”

“Aye aye, sir,” Westcott said, doffing his hat most formally, again, sure that this would be a very hot business. He turned away to begin issuing Lewrie’s orders.

The French battery atop the hill had been busy during their slow approach, sending roundshot chasing after departing transports, but, after finally taking notice of such a big and tempting target, they began to shift the aim of their guns, even before Sapphire got to her optimum firing position.

“I think this will do, sir,” Yelland said at last.

“Very well, Mister Yelland. Let go the kedge, springs on the cable!” Lewrie cried. “Topmen aloft, trice up and lay out t’take in sail! Open the gun-ports and run out!”

Shot keened overhead, and the main tops’l puckered as a shot punched clean through it. Another roundshot snapped the halliards of the middle stays’l between the main and foremast, bringing it down to drape the waist.

Sapphire rumbled and groaned as the kedge anchor cable paid out the stern hawsehole, squealed as the sheaves of the gun-port blocks lowered the ports, roared and drummed as the larboard guns were run out to thud against the bulwarks and hull. She snubbed as the kedge bit into the rock and sand of Corunna’s harbour, and began to ghost to a stop.

“Seize, and bring to!” Lt. Westcott could be heard yelling to snub the kedge cable. “Breast to the aft capstan bars! Mister Ward!” he called to the forecastle with a brass speaking trumpet. “Let go the bower!”

A 12-pounder shot passed close over the poop deck, clearing the larboard bulwarks by inches, but smashing the cap-rails of the starboard bulwarks as it caromed off. The Sailing Master and his Mates came tumbling down from where they had been making their calculations in a trice.

“Pass word to the gun-decks,” Lewrie ordered, “quoin blocks all the way out, load, and lay the guns!”

The first serge cartridge bags were being rammed down muzzles, followed by wadding, then roundshot. Lewrie leaned over the side to see the 12-pounders and lower deck 24-pounders jutting from the side, barrels jerking upwards as the wooden elevating quoin blocks were withdrawn, allowing the breeches to rest on the truck carriage beds.

Westcott was back at Lewrie’s side, speaking trumpet still in his hand, and they shared a look in the moment it took for Mids to dash up from below and report the guns ready. Lewrie gave him a nod.

“The larboard battery will open,” Lewrie gravely ordered, “by broadside. And skin the sons of bitches!”

“Larboard battery … by broadside … fire!” Westcott yelled.

Unconsciously, Lewrie crossed the fingers of his right hand along the side of his thigh as the guns lit off in a titanic roar, a sudden fog bank of powder smoke, and amber-red flashes of jutting flame that erupted from her side.

“Two-thirds of a mile, you made it, Mister Yelland?” Lewrie asked, turning to look for the Sailing Master.

“Aye, sir, about that,” Yelland said through a dry throat.

“Can’t see a bloody thing,” Lewrie groused. “Mister Harvey,” he called to the nearest Midshipman. “Aloft to the cross-trees with a telescope, and spot the fall of shot!”

“Aye aye, sir!” the lad said, snatching a glass from the binnacle cabinet rack and making his way to the larboard main mast shrouds.

The first broadside’s smoke was wafting away over San Diego Point, and Santa Lucía Hill was emerging once more.

If we can’t take their fire, we can get the bower up and the wind’ll blow us back on the kedge, then wheel back out to sea, he thought, taking time to look over to starboard at the other ships in port. Fully laden ships were shifting their anchorages further out of range of the French guns, some in groups that were leaving the harbour to stand off-and-on outside. The one transport that had been hit several times looked to be in a bad way, her main topmasts hanging over, her yards a’cock-bill in disorder, and listing a bit to starboard. At least the French weren’t firing at her, anymore.

“Run out yer guns!” Lieutenants Harcourt and Elmes could be heard from below as they pressed their gun crews to prepare for one more broadside.

“Shot was high, sir!” Midshipman Harvey yelled from aloft. “High and right!”

“Quoin blocks in a bit, Mister Westcott, and take in on the kedge cable spring!” Lewrie snapped, impatient for the adjustment in aim to be completed.

“Ready!” was shouted up to the quarterdeck.

“By broadside … fire!” Lt. Westcott yelled, and Sapphire shook and roared as the guns lit off, as the truck carriages came rushing back in recoil. “Better aim as the barrels warm up, sir,” he said to Lewrie, with a confident wink.

A full battery of French artillery consisted of several 8-pounder guns, at least six of their famed 12-pounders, and a brace of howitzers. All were firing at a fixed target. Shot splashes towered close to the larboard side, Sapphire drummed to a solid hit, and a howitzer roundshot crashed down onto the starboard sail-tending gangway with a raucous shriek of rivened, splintered wood.

“Still high, sir!” Midshipman Harvey shouted over the din to the deck. “Traverse is still just a bit to the right!”

“Pass word, quoins in another inch,” Lewrie snapped, “and take another strain on the kedge cable spring!”

“Ready?” Westcott demanded after the adjustments were made. “By broadside … fire!”

What I’d give for fused shells! Lewrie bemoaned as the broadside bellowed, flinging heavy shot shoreward through the sudden pall of smoke. He’d dealt with fused mortar shells and bursting shot when he’d been at Toulon; he knew the dangers of such tricky, delicate shells being rammed down hot barrels, perhaps lighting the fuses as they were rammed down and bursting, destroying the guns and killing gunners. As he wished that he had stuffed some candle wax in his ringing ears, he began to imagine how that could be managed, despite the risks.

“Traverse is true, sir!” Harvey screeched, sounding triumphant. “Our shot is skimming the hill, by inches, I think!”

“Quoins out half an inch!” Lewrie shouted. “Serve the whores another!”

“Ready? By broadside … fire!” Westcott roared.

“Yes! Yes, that’s the way!” Midshipman Harvey yelled, far above the massive smoke clouds and able to see.

French shot was still striking close aboard, the ship boomed to hits crashing into her thick timbers and stout scantlings, and wood shrieked and squawked as the lighter upper bulwarks were ravaged. The fore course yard was hit, amputated just below the foremast fighting top, and both ends of the yard sagged downward in a steep V to drape furled canvas, and snap brace line, clews, and jeers. A Marine tumbled from the foremast fighting top with a thin scream, crashing to the deck in a pinwheel of arms and legs.

“Spot … on, sir!” Harvey reported, going hoarse.

“Pass word below,” Lewrie yelled, “our aim is spot on, and no adjustments are needed! Pour it on, Mister Westcott, pour it on!”

He lifted his telescope as the smoke thinned once more, peering hard to see the results of that last broadside. He saw raw divots in the slope just below the French guns, where roundshot had hit short and buried themselves, some lines ploughed a bit further upslope where other shot had ripped long troughs in the earth, as if God had drawn His fingers to rake at the French.

Damme, is that an over-turned gun yonder? he wished to himself.

Two-thirds of a mile range was just too far to make out close details, even with his strong day-glass, but he could make out French gunners scurrying to fetch powder cartridges from the limbers, which were hidden behind the crest of the hill. Their cannon and their wheeled carriages were little black H-shapes, surrounded by gunners who wheeled them back into position, fed their maws with powder and fresh shot … all pointed directly at him; he was looking straight down their muzzles!

“By broadside … fire!”

“Dammit!” he spat as his view was blotted out, lowering his telescope in mounting frustration. He wanted to see!

Climb the shrouds, high as the cat-harpings? he thought; No, it wouldn’t be high enough. I’d have t’join Harvey, and I’ve not been in the cross-trees in ages!

There were some good things about being a Post-Captain, or pretending to be one, after all!

“A gun dis-mounted, sir!” Harvey yelled down.

Lewrie whipped up his telescope again as the smoke cleared to a haze and did a quick count of the little H-shapes. Yes, there was one of them leaning to one side, with no one standing round it!

“Serve ’em another, Mister Westcott!” he roared.

Firing, running in, swabbing out, loading, then running out and shifting the aim with crow levers; he lost track of how long Sapphire kept up her fire; he lost count of how many times his ship was hit. After a time, though, reports of damage came less often, and Midshipman Harvey’s shouts became more excited, raw and rasping as his throat gave out. Finally …

“Deck, there!” Harvey cried. “They are bringing up limbers! Three guns dis-mounted … they are retiring!”

Lewrie took a long, hard look, even though his eyes burned from all the irritants in gunpowder smoke, blinking away tears, swiping at his face with the cuffs of his coat sleeves.

Yes, by God! he told himself; They’ve had enough of us, they’re pullin’ out!

Horse teams, which had been sheltered near the caissons of shot and powder cartridges, could be seen near the surviving guns, being hitched up; carriage trails were being lifted to re-assemble guns to the limbers. One by one, the French battery was withdrawing to the shelter behind Santa Lucía Hill!

“Cease fire, Mister Westcott,” Lewrie bade in a croak through his dry and smoked throat. “Cease fire, and pass word below that we shot the living shit outa those bastards! Damn my eyes if we don’t have the best gunners in the whole bloody Fleet, tell ’em!”

“Took the better part of two hours, but we did it, sir,” Westcott said, grinning fiercely, his white teeth startlingly bold against the grime of gun-smoke that had coated him from head to toe.

“It did?” Lewrie said in wonder. “I didn’t keep track. Secure the guns, see that the hands have a turn at the scuttle-butts, then let’s take in the bower, make sail, and fall down on the kedge.”

“Aye, sir, I’ll see to it,” Lt. Westcott promised.

“Mister Yelland, still with us?” Lewrie asked, turning round to survey the quarterdeck.

“Here, sir,” the Sailing Master said. “My congratulations to you, sir.”

“Mine to you, sir,” Lewrie replied, shrugging off the compliment with a weary modesty. “I wonder, sir … might you have a flask on you?”

“Just rum, sir,” Mr. Yelland said, sounding apologetic.

“I think we’ve earned ourselves a ‘Nor’wester’ nip, don’t you, Mister Yelland?” Lewrie asked.

“Why, I do believe we have, sir!” Yelland cried, breaking out into a wide smile as he handed over his pint bottle.

* * *

“There is a hoist from Admiral Hood’s flagship, sir!” one of Undaunted’s Midshipmen announced to the officers on her quarterdeck. “It is … Sapphire’s number, and … Well Done, no … spelled out … Bravely Done!”

“And so it was,” Captain Chalmers said with a vigourous nod of his head, “though I do wish that Captain Lewrie had summoned us to aid him.”

HMS Sapphire was standing out from her close approach to the shore, gnawed and evidently damaged, but putting herself to rights even as she made a bit more sail. Captain Chalmers could hear the embarked soldiers and transport ship sailors raising cheers as the old 50-gunner Fourth Rate passed through their anchorages. Ship’s bells were chimed in salute, clanging away tinnily like the parish church bells of London. Chalmers’s own crew was gathered at the rails waiting for their chance to cheer, her, too. He looked round cutty-eyed to seek out Midshipman Lewrie, and found him up by the foremast shrouds, safely out of earshot.

“Pity that the ‘Ram-Cat’ is such a rake-hell of the old school,” Chalmers imparted to his First Officer in a close mutter. “He don’t even have a Chaplain aboard! From what I’ve heard of him, it’s doubtful if one could even call him a Christian gentleman. A scandalous fellow, but a bold one. Runs in the family, I’ve heard.”

“Surely not in his son, sir,” the First Officer said.

“Perhaps we’ve set him a finer example, and altered the course of his life,” Chalmers said, congratulating himself for being one of the principled, respectable, and high-minded sort.

Then, as HMS Sapphire began to come level with Undaunted, about one cable off, Captain Chalmers doffed his hat, waved it widely, and began to shout “Huzzah!”, calling for his crew to give her Three Cheers And A Tiger!

Scandalous reprobates still had their uses.