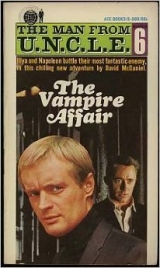

Текст книги "The Vampire Affair"

Автор книги: David McDaniel

Жанры:

Боевики

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 3 (всего у книги 9 страниц)

"Will you be going home before midnight?"

The Colonel did not answer.

"Are you...cautious of the threat your village is under?"

Hanevitch rose to his feet and pulled in his stomach. "The government tells me the rumors of vampires are the superstitions of uneducated peasants. I am a sincere and dedicated Communist, and Marx said nothing about undead spirits. This outrage has a material cause, and my Tokarev can stop anything material and unarmored." He slapped his hand against the bulky Russian automatic strapped to his side.

Illya slowly and casually seated himself in a convenient chair. "Napoleon," he said without turning his head, "you and Hilda go ahead to the inn. I would like to continue conversing with Colonel Hanevitch for a while. After all, midnight should be no deterrent to two rational men."

Napoleon started to object, but Hilda poked him in the arm. "Come on, Napoleon," she said. "Am I the only one here sane enough to admit I am not rational? Or are you going to let me walk through the night alone?"

Solo opened and closed his mouth two or three times, and waved his hands to emphasize whatever he was trying to say. At last he heaved a deep sigh and said, "I think you're all crazy! Come on, Hilda; when Illya gets an idea like this in his head there's no reasoning with him."

As they closed the door behind them, they heard Hanevitch's voice saying, "Now, Mr. Kuryakin, what precisely was the cause of your leaving Russia?" Napoleon would have given a great deal to hear the answer, but Hilda had his sleeve and was stronger than she looked.

* * *

"What time is it, Napoleon?" asked Hilda, as she looked around the room where the U.N.C.L.E. agents would be staying.

"A few minutes short of eleven," he answered, checking his watch. "Why?"

"I just wondered," she said slowly. "It feels like midnight."

They had come into the room only a few minutes before, Hilda carrying one bag and Napoleon carrying two from the car, which had been left behind the Satul Contru. The room was on the third story of a large inn which must have dated back to a period of greater travel in the mountains. The ceiling was low and slanted, and the beds were large and soft, with heavy down comforters. A heavy silver pitcher of water stood in a matching bowl on the dresser, with a glass beside it: Gheorghe had been appraised of his guests' importance, and had brought out a family heirloom for their especial use. Hilda mentioned this to Napoleon, who made a note to be unusually grateful. There was also a modern table with two chairs in the center of the room, flimsy by comparison with the sturdily-built furnishings which matched the wood-raftered decor.

Napoleon didn't need to ask what she had meant by her remark that it felt like midnight. He had felt ill-at-ease since coming into the room, but he put it down to accumulated tiredness and the strangeness of the surroundings. He shook his head to clear it, and poured himself a glass of water.

He wandered around the room sipping at it, while Hilda flopped into one of chairs and watched. She tried to look relaxed, but her hand gripping the arm of the chair quivered with nervous tension. Napoleon felt it too—an unreasoning panic slowly growing inside him. He remembered a gas that caused blind fear like this in its victims, and went to the window. He threw the casement open and breathed deeply of the cold, sharp night air. It woke him up somewhat, but did nothing to ease his agitation.

He closed the window again and latched it securely, then strolled back towards Hilda. "Look," he said, as he set his empty glass down on the table. "It's late, and you've been under a terrific strain. I suggest strongly that you go back to your room, lock the door, and sleep till noon. You'll feel a lot better."

Somewhere a tall clock began chiming. "It's eleven o'clock," he continued, glancing at his watch. "We can discuss..."

Hilda held up her hand, listening. The clock chimed ten, eleven—and twelve. She looked up at him. "Did you set your watch ahead when you crossed the border?"

He thought. "Illya reminded me," he said, "but did I? I don't think I..."

Hilda's hand jumped for his wrist and grabbed it hard. She was staring past him, eyes wide with fear. Her mouth opened slowly, and she said in a strange whisper, "Napoleon—look at the glass on the table."

He turned, gently disengaging her hand, and looked. The glass he had just drunk from was crawling slowly across the top of the table. He stared at it in disbelief for a few seconds, and then reached out almost unwillingly as it approached the table's edge. He picked it up and looked at it, then set it down in the center of the table again. Immediately it began to move toward the edge. Not fast, but quite visibly. Hilda was shrinking back in her chair, staring with horrified fascination at it. Napoleon picked it up again, then quickly looked under the table. It was too light to have any kind of mechanism concealed inside it, practically cardboard and lath. He started to say, "There's a perfectly logical explanation..." But his voice failed him, and he swallowed hard.

The thought in his mind was Why is it moving?, but the only feeling in his stomach was primitive fear. He fought to control it. With a shaking hand he reached for the water pitcher. "Let's see if whatever it is can move half a pound of water," he said almost conversationally. Then Hilda screamed.

Napoleon could see the room behind him weirdly distorted in the bright surface of the pitcher—the light walls and the black curved rectangles of the windows. And there was something moving outside the windows. Something so distorted by the curvature of the metal he couldn't tell what it was.

He whirled on his toes and cocked his arm. In a fraction of a second he saw a black shape standing just outside the window, and his mind photographed it: almost as tall as one window and with a wingspread as wide as both, and with a face almost human but unbelievably baleful glaring into the bright light of the room. Then Napoleon hurled the pitcher with all his strength and the glass exploded outward in a shattering burst of sparkling shards.

A moment later there was the sound of a shot from below. Napoleon opened his eyes again, and realized he had closed them just as he had thrown the pitcher. He ran to the window, and looked down twenty-five feet to the muddy street below. He looked up into the darkness. There was no sound, and only the feel of a vagrant breeze stroked his cheek with a clammy finger.

He looked down again, and saw Illya standing, legs apart and braced, gun in hand, looking up at him.

"What did you see?" Napoleon asked.

"I don't know," countered Illya. "What do you think you saw?"

Napoleon shook his head. "I don't want to say right out loud because I didn't get more than a glimpse of it. I couldn't identify it in a lineup." But as he spoke the picture came to him, as sharp and clear as a studio photograph, of a face in the midst of the floating, flapping blackness, just outside a third-story window with no balcony....

"Come on up," he said. "And if you see Gheorghe, ask him for something to cover this window. No, forget it. We'll take another room. Oh, if you see a pitcher down there, bring it up."

Ninety seconds later Illya tapped at the door and Napoleon opened it. "Find it?" he asked.

Illya slipped his automatic back into its holster. "We can look for it in the morning," he said. "Is Hilda all right?"

"She's coming around. Now, tell me before she comes to—what do you think you shot at?"

"I don't know. I looked up when I heard the glass shatter, and I saw something outside the window. I know it didn't go down the side of the building or over onto the roof, because I saw it go away from the wall as if it was jumping, but then it went up into the dark."

"Illya, what do you think you shot at?"

The Russian agent sat down heavily and looked at the back of his hands. "Napoleon, we've been friends for a long time. You know I am not given to hallucinations or to letting my imagination run away with me."

"Yes...."

Illya looked up. "And don't mention this in our report—but it looked like a huge bat."

Section II: "Werewolves Can't Climb Trees."

Chapter 5: "Good Lord, Illya—What Was That?"

It should cause relatively little surprise that neither Napoleon nor Illya slept particularly soundly that night. The innkeeper was quick and efficient about transferring them to another room, and made no comment about his valued heirloom being thrown through a window and left in the mud of the street all night. He also showed no inclination to go outside to search for it. "There will be time enough for that in the morning," he said. "My friends are honest, and know to whom it belongs if they find it."

After he had left, there was a brief debate with Hilda, who absolutely refused to return to her own room.

"I don't care what you tell New York," she said, "and I don't care what Gheorghe thinks—I'm spending the night on your sofa. I know what I saw at the window, and I know I won't sleep a wink if I'm alone."

Illya remained aloof from the discussion, and reappeared after a few minutes' absence dressed in pajamas of a plain dark blue. "And I know what I think I saw," he said. "But I refuse to allow it to interfere with my rest. If you two insist on arguing the night away, please do it in lower tones."

He climbed into bed, pulled up the covers, and turned his back to them. Napoleon and Hilda looked at him for a few seconds, and then Napoleon heaved a deep sigh of resignation. "All right," he said. "It's your reputation. If there wasn't a third party here as witness..."

"You wouldn't be nearly so hesitant," said Hilda, with an impish grin as her apprehension lessened. "Come with me back to my room while I get a few things."

"And leave me here all alone?" came Illya's muffled voice from the bed.

"Don't worry," said Napoleon comfortingly, "I'll leave the light on for you."

Then he ducked quickly to one side as a pillow flew across the room and slapped against the door.

* * *

A discrete tap at the same place several hours later announced that breakfast was being prepared, and some fifteen minutes after that the three descended the stairs, freshly dressed and looking ready for anything under the sun. Under the moon might be a different matter.

There was no discussion of last night's occurrences over the breakfast sausages and eggs. The conversation moved around local customs and traditions, and only faltered for a few seconds when Gheorghe silently poured fresh milk for them from a freshly cleaned and polished silver pitcher which Napoleon recognized.

At last, over coffee, they got down to the business of the day.

"I could draw you a sketch map," said Hilda, "but I couldn't show you the exact spot except in person."

"How far away is it?" asked Illya.

"A little over a mile from the outskirts of the village. He was running in this direction."

Napoleon frowned. "I suppose the place will be all trampled by curious villagers by this time."

"I don't think so. These people have better things to do with their time than wander about in the woods. And they have lately been more cautious than usual. In fact, I would be surprised if anyone from the village had been near the spot where Carl was found. They consider it a place of ill omen."

"It was for Carl," said Illya.

"When will you be ready to show us the place?" Napoleon asked.

"Any time. The spot's fairly close to the road; if you have any sort of detecting gear to carry or want to avoid a long walk in the forest, we can drive."

"Beats a long walk carrying my magnifying glass. How about you?" Napoleon turned to Illya.

"For myself, I can take nature or leave it alone. The car will probably be quicker, unless the road winds."

"Not that much. I can drive you there in five or ten minutes."

"Make it fifteen," said Napoleon. "I've got to get my pipe and deerstalker hat out of my trunk. If we're going to play detective, I may as well look the part."

* * *

The lumbering old Poboda took the rutted dirt road with only a few complaints, and eight bumpy minutes after leaving the garage behind the City Hall Hilda pulled to a stop in a wide area. There was enough space for a cart to pass, but not much more.

The trees were not thick—perhaps ten feet apart. There was little underbrush. The forest had a well-kept feeling to it, and an almost park-like appearance. There was only the slightest wind breathing among the upper branches of the pines, and the occasional note of a bird rang distantly like a dropped coin.

Napoleon and Illya felt the quiet of the place pressing softly in around them, and even the warm morning sunshine seemed a little chill. Hilda broke the silence.

"This way," she said. "Just over that little rise."

She pointed the tree out to them from a fair distance away, and described without a trace of emotion her own deductions as to the last few minutes of Carl Endros' life.

"He broke out of the underbrush about there," she said, pointing. "I was able to back-trail him about half a mile, and found no indications of anyone or anything on his track. No footprints of any kind."

"What about right around the body?" asked Illya.

"None that I could see. The ground was scuffed up close to the base of the tree, and I couldn't read many signs. I could see where he had tripped over the tree root and dragged himself to where his back was protected, but I couldn't tell whether there were any footprints close to him. There were certainly none approaching."

"Could they have stepped in his footprints?" Napoleon suggested hesitantly, half afraid it would sound foolish.

It did. Hilda regarded him scornfully. "Really, Mr. Solo," she said. "Even if they had been wearing the same type and size of shoes, it is practically impossible to step exactly in an existing footprint. Try it with a print of your own. There will almost always be a double impression of some kind. And while you might match one or even two, ten or twelve consecutive prints would be most unlikely. Especially since they must have rushed him as he was shooting."

"Oh yes," said Illya. "Shooting. Have you checked the trees for slugs? If he emptied his gun, they must have gone somewhere."

"I've made a cursory examination of the nearer trees," she said, "but haven't had the time for a careful and detailed search. Why?"

"A relatively undamaged bullet may give us an indication of where it has been," said Illya. "Whether it bounced off something, hit nothing but the tree in which it stopped, or passed through something, and whether that something was flesh and blood or not. It could be most interesting."

* * *

They returned to the village shortly past mid-day, for lunch and rest. Several dozen trees had been examined, and two possible bullet holes found. In both cases the slugs, if slugs there were, were buried too deep for casual extraction with a pocket knife, and would have to be dug out by stronger methods. There was a small hand-axe in one of their boxes of equipment which should prove itself equal to the task, and with which they planned to return after refreshing themselves.

They were seated on the porch of the inn awaiting their ciorba, and sipping at a local white wine, when the sound of voices raised in anger came along the street to them.

"I wonder what that is," said Napoleon with slight interest.

"Sounds like a small riot," Illya suggested.

Hilda looked doubtful. "A riot? In Pokol? I don't believe it."

"We shall soon see," said Illya. "It sounds as if it's coming this way."

And a few seconds later a tall slender man, dressed in a black suit of formal and slightly old-fashioned cut, hurried around the corner, casting glances over his shoulder. As he approached the inn, he slowed and looked up. It took Napoleon a few seconds to recognize him as Zoltan, whom they had helped in a similar situation in Budapest some five days ago. He poked Illya.

"It's Zoltan," he said. "Our friend from Budapest. Looks like whatever he does, he did it again. Should we wade in and help him out, or figure if it happens this often maybe he deserves it?"

"We can accomplish little here without the coöperation and trust of the people of the village," said Illya. "Let us see what happens if we don't take a hand."

There was a larger crowd after Zoltan this time—some twenty men and women were following him, many of them waving scythes or brooms. Zoltan was still a good thirty feet ahead of them as he gained the steps of the inn, mounted half-way up them, and turned to face the crowd. He raised his arms, and they stopped.

"My countrymen," he addressed them in Rumanian, "your suspicions of me are understandable. You know the old stories and you have seen the old spirits walking in the forests. But I am one of God's children, like you. And if there is any man among you who questions my true nature, let him come with his friends to the church this afternoon when the bell tolls the hour of one, and let him apologize before the altar to me and my family."

There was a mutter from the crowd, and some of them moved a step forward, but Zoltan stood firm.

"The church, within the hour," he repeated. "I wish to remain in this village for some time, and I want no one here to consider me an enemy or to walk in fear."

Without waiting for a response, he turned and went up onto the porch. He seemed about to walk past them into the inn, so Napoleon greeted him quietly:

"Good afternoon. I believe we met in Budapest a few days ago."

The thin aristocratic features turned in their direction, and then softened into a smile of recognition. "Ah, yes," he said in English. "Mr. Solo and Mr. Kuryakin, of New York, America. I had half expected to find you here. I don't believe I know your charming female companion."

Hilda smiled up at him prettily, and Illya performed the introductions. "Hilda Eclary, this is Zoltan...ah..." He looked up at their guest. "I don't believe you ever gave us your last name."

A brief smile flickered across his thin face. "I'm certain I didn't. It is not given lightly."

Napoleon hooked a fourth chair with an outstretched leg and dragged it to the table. "Well, why not sit down and have a glass of wine, and tell us your life story."

"I cannot partake of wine or any other food for an hour or more, my friend, but at half past the hour of one I will be more than pleased to accept your invitation. You see, at one o'clock I must take holy communion in the church, or I cannot rest in this town."

Napoleon and Hilda looked at each other, and then they looked at Zoltan. Before they could phrase the questions that were bubbling in their minds, Zoltan raised a slim, well-manicured hand. "My name will answer all your questions," he said. "I am the heir to a no-longer existent title, and the last son of a noble and aristocratic family. But my name is a curse which has followed me around the world." He looked them over, and said in a perfectly level voice, "I am Count Zoltan Dracula."

* * *

At twenty minutes past one, Napoleon and Illya stood outside the little Orthodox church where they had just watched, with most of the population of the village, as Zoltan Dracula said the words of prayer, kissed the silver cross of the priest, and took communion. No man in Pokol could have been found willing to admit he had thought it impossible, but several had stayed behind to shake Zoltan's hand and apologize, though they didn't say for what.

"Well," said Illya as they started for the door, "there's one we don't have to worry about."

Napoleon looked oddly at his partner. "Worry about what?"

"Never mind, Napoleon. There's just one we don't have to worry about, that's all."

Colonel Hanevitch was one of the few absent from the ceremony, but he met Napoleon and Illya as they came out of the cool darkness of the church into the bright mountain sunlight. Illya greeted him.

"Good afternoon, Colonel. Did you miss the mass?"

"Of course not. I am a good atheistic Communist, and I have no time to spare for these peasant superstitions." He paused. "I presume nothing...untoward happened?"

"I beg your pardon?"

"The ceremony was unmarred by any...unusual occurrences, and was completed properly?"

"Of course," said Illya with a slightly raised eyebrow. "Did you expect anything to happen?"

"Oh, certainly not, certainly not," said the Colonel hastily. "I was simply inquiring of politeness. And I came only to speak to Domn Dracula about his plans while here. He has no legal standing, you understand, except as an expatriate visitor; his title is meaningless."

"And his name?" asked Illya softly.

"Is merely a name," said the Colonel definitely. "If the people choose to attach meanings to it, my only duty is to protect our visitor from the results of their misinterpretations."

"I don't think there is much danger of that," said Napoleon, as Zoltan came out between the tall wooden doors, surrounded by well-wishers, and with Hilda right behind him.

He raised a hand to hail the U.N.C.L.E. agents as he approached, then turned to the crowd. "My people," he said. "I hold no ill-will. I ask only that in the future you remember this—a name alone holds no evil. Now my blessing on you all. Return to your work." And obediently they were gone.

Zoltan turned to Colonel Hanevitch. "You wished to speak with me, I believe? Food has not passed my lips today, and while my soul is strengthened, my body is weak. Could we speak at the inn, over ciorba and mititei?"

They did. Napoleon had remembered something though, and opened the conversation before the Colonel had a chance to speak.

"I seem to remember the Dracula family actually died out in 1658," he said without preamble.

"Yes," said Illya. "But not in the south."

"Quite correct," said Zoltan. "There were originally two brothers, Dan and Dragul, who founded rival lines in the 13th Century; lines which were not to merge until almost 1600. But when Constantine Sherban died childless in 1658, the title devolved to a distant relative, my seven-times-great grandfather, Petru. The family name was Stobolzny, but the title Voivode Drakula became part of the family heritage. At the time, it was not politically expedient to have this known, and the documents were hidden. Then they were lost, and not found again until the castle was rebuilt in 1897. We were ready to reëstablish our title when that accursed Englishman, Stoker, chose to make the name of Dracula known to the world as the name of a demon.

"My grandfather thought it beneath his dignity to sue, and besides, the damage had been done. But in this modern and rational age, I thought, there would be no real belief in the terrors of the darker parts of our past. So, proud of the true heritage of my family title, I took the name which was rightfully mine. And since then I have defended its honor in every country in Europe. Now I have returned to the home of my people. The castle where I played as a child has been taken over by strangers; my title is meaningless. But the people still know me, and I know the land. I have money—perhaps I can ransom my castle from those who now hold it, and live in my home again."

He took a large bite of sausage and followed it with a hearty swallow of wine. "And there you have my story," he said. "Colonel Hanevitch, have you any questions?"

There was silence for perhaps a count of ten, and then the Colonel rose stiffly to his feet. "I remember your father well. You know the present situation, and I feel you can be trusted not to infringe upon it." His face softened as the trace of a smile rose under his discipline. "And may I say, welcome home, Voivode Drakula." And he turned on his heel and marched away.

Illya looked after him with mild surprise, and murmured, "You know, I may have been wrong about the Colonel. Perhaps he is human, after all."

* * *

The afternoon was more than half gone when Napoleon and Illya returned to the spot in the woods where Carl's bloodless body had been found. A radio check with Geneva had established Zoltan's bona fides, and Hilda had stayed behind to enlist his aid in their investigation. Meanwhile, they had field work to occupy their time.

They carried with them small hand-axes and large hunting knives, and after parking the car just off the road and walking to the scene of the crime they set about attacking a group of nearby trees with these weapons.

Careful examination had revealed bullet scars in these trees, and there was a chance that the jacketed slugs could have been left relatively undamaged by their flight, and that something might be learned from them.

But the trees were hardwood, and the job was slow and tiring. The first slug retrieved had apparently glanced off another tree and then lodged against a knot; little identifiable remained of it.

It took almost an hour to find another bullet hole. By this time the second slug had been extracted and was found to be in reasonably good shape. Both men went to work on the third tree.

Gradually Napoleon became aware that it was growing increasingly hard to see. The sun had dropped behind the mountain peak to the west some time ago, but now the light was fading rapidly. In a few more minutes it would be dark. As he looked up from his work, a sound like a chiming clock directly over his head made him start.

Illya looked up for a moment, then bent to his work again. "A dwarf owl," he said. "A startling sound if you don't expect it." He straightened and rubbed his eyes. "I seem to remember a flashlight in the car. We can have this out in another fifteen minutes, if we can see what we're doing."

He slipped his knife back into its sheath and started off. "Come on," he said to Napoleon. "In these woods at night, it takes two people to carry a flashlight."

"Is that an old folk saying?"

"No, I just made it up. But do you deny its truth?"

Napoleon laughed briefly, but he came along.

At the road, they looked up and down in the deepening twilight. "It must be some other part of the road," Napoleon suggested doubtfully.

"We left it right over there," said Illya, pointing. "See the stump by the wide place? That's where we parked. I remember it clearly because I put the front fender right next to it."

Napoleon followed him over to the stump, and held a cigarette lighter while he examined the ground closely. "The road is too hard to hold tracks," said the Russian to himself. "But here's the wheel-mark next to the stump. It ends here, too."

Solo bent and looked where Illya's finger pointed. There was a depression the size and shape of the tire-tread running in from the road and ending by the stump—the car could have been backed out by someone, but they had not heard the motor, and the Poboda was not well-muffled.

He straightened and shrugged. "It's been stolen," he said. "Looks like we hike back to the village and tell the Colonel we've been the victims of a simple old-fashioned car theft."

"I hope it's that simple," said Illya. "I've long ago learned that true coincidence is a very rare thing. There may be some sort of trouble tonight before we get back to Pokol."

Napoleon was about to ask a foolish question, when the darkness was shaken by a long anguished wail which seem to come from somewhere up the road. He stopped with his mouth open as the silence softly flooded back in upon them. Then he almost whispered, "Good Lord, Illya. What was that?"

A moment later the howl was repeated—this time in the woods directly behind them, sounding less than a hundred feet away.

In the silence that followed, Illya's voice said quietly, "I'd hate to guess, since wolves are supposed to be rare in these mountains. But I think I can definitely say that is not a dwarf owl."

Chapter 6: "My Pets Seem To Be Restive Tonight."

They started slowly along the road towards town, keeping in the center of the road, and had gone a hundred paces before each realized he was holding his U.N.C.L.E. Special automatic loosely in his hand. It was quite dark now, and a fog had blown down from the mountains above them. The temperature was dropping too—Napoleon was glad for the heavy overcoat he had thought to bring along.

Neither one of them spoke. Both were aware it was about two miles to the village, and they were equally aware that if they stayed on the road it would take them about half an hour. If they wandered off the road they would be lost, probably for the whole night.

They had gone almost a quarter mile in absolute silence. Not even the sound of a night bird penetrated the fog. And then both stopped and raised their guns instantly as another howl came out of the darkness ahead of them. And as they stopped, they heard a soft sound behind them—a padding of soft feet and the heavy breathing of a large animal.

Napoleon spun around, but could see nothing. He said so. Illya did not answer, but pointed. The shapes of the trees were dimly visible on either side of the road, and as they looked, something large and gray moved across a space and disappeared again.

"We seem to be cut off," he murmured. "A pack is hunting tonight."

"Would it help to climb a tree?" asked Napoleon uncertainly.

"It might. But if you will notice, the pines large enough to support your weight do not branch until some twelve feet above the ground. My athletic skills do not include the high jump."

They looked about them for a moment. The sounds behind them on the road stopped, then came cautiously closer. Another blood-chilling howl sounded in front of them, and another to their left.

"Let's go this way," said Napoleon impetuously, pointing right.

"Leave the road?" said Illya doubtfully.

"I'd rather be lost for the night than permanently," said Napoleon. "We have eight rounds each in these rods, and I wouldn't want to count on them being enough to discourage our furry friends out there."

"I think I see your point," said Illya, and they stepped off the road.

Almost at once they were surrounded by pitch blackness. Napoleon could avoid bumping into trees by walking cautiously and keeping his hands extended. He could usually spot a tree a few feet away as a lump of darker black, but it was a risky business. City-bred eyes do not adjust to absolute darkness easily.