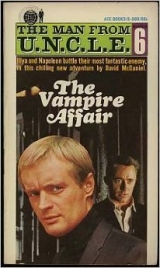

Текст книги "The Vampire Affair"

Автор книги: David McDaniel

Жанры:

Боевики

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 9 страниц)

The Vampire Affair

By David McDaniel

The body had been drained of blood....

In a remote area of the Transylvanian Alps, an U.N.C.L.E. agent had been killed in mysterious circumstances. The man's footprints in the snow led up to the base of the tree where he had been killed, but there were no pursuing tracks, no clues at all as to what doom had overtaken him.

There were only the two small holes in the neck, and a complete absence of blood.

Napoleon Solo and Illya Kuryakin didn't believe in vampires—but as they investigated their fellow-agent's death they were forced again and again to wonder if perhaps the old terrors of the region had more reality than the world would like to think....

THE VAMPIRE AFFAIR

It had begun to snow. The bare black branches of the trees clutched at the lowering white sky with bony fingers, and the dark earth was flecked with bright patches like a leprous mold. The sparsely scattered pines spread impenetrable shadows in the dimness, and the wind whispered rumors of ancient and instinctive fear among their hissing needles. The rustling of air seemed to be the distant voices of spirits of the darkness, filling the forest silences with an undercurrent of unease. Nothing moved in the cold stillness except the textured white blanket above and the softly falling flakes.

Then a sound began, very faintly. It was a quick soft thudding of feet on dirt, like the beating of an overstrained heart. There was a slight irregularity to its rhythm, and an occasional cracking of a twig. As it grew, a figure appeared between the trees—a figure running, stumbling as though exhausted, and finally stopping, slumping against a pine trunk.

As the footsteps ceased, wheezing gasps sounded loud as he fought to draw air into his straining lungs. His coat was open despite the cold, and his tie was loose. Sweat poured down his face and ran down his neck, where the large vein pulsed violently from his exertion. His chest ached, and his legs were stiff and numb.

He couldn't remember how long he had been running. But he knew he wouldn't be running much longer. The weakness of total fatigue was spreading through his system like a slow poison, and his muscles were beginning to stiffen up as he stopped in the cold trying to regain his breath. The icy night air burned in his dry throat.

He managed to hold his breath for a few seconds, and listened hard. There was only silence, except for the pounding of his heart. Then he heard it. Gusts of wind began to whip the trees, and a rustling sounded behind him as of a large body forcing its way through the brush. There were other noises coming towards him—not fast, but never stopping.

He pushed the pine tree away, and balanced himself on his feet. He had to run—to keep running. His mind refused to think of what would happen if he stopped, or fell, or slowed, and was caught.

Something was after him in the darkness—more than one thing. He didn't know what they were. His mind supplied formless horrors with fangs and claws, and his body fled through the darkness from them.

Now he could hear them, closer behind them. The wind was whipping around him now—a strange directionless wind that caught up the snow and dried pine needles and whirled them about him, clutched at him and tugged at his clothes. And over the wind he could hear soft running footsteps keeping pace with his own, and animal pantings behind him and to the sides.

The wind grew, and the trees around him writhed with it. On he ran, leaden legs sinking into the soft earth of the forest floor, chest bursting for air. He knew they were close behind him now, and the flesh of his back tensed and crawled, expecting the impact of the deadly pursuers and the tearing pain of razor teeth.

He had thought he had escaped them once. He had stopped to rest against a pine tree, for a blessed moment of release from the endless flight, and a few seconds to catch his breath, but then they had been after him again. Were they playing him? Were they going to run him until he collapsed and begged for death, or until he could see the lights of the village and sanctuary? Would they harry him until he was almost on the steps of the church and then strike him down on the brink of safety?

If only he could save a wisp of strength, an atom of energy, held out for a final spurt that could put him beyond their reach—then there might be a chance. He could never give up hope; if he did, he might just as well lie down in the dirt and die now.

But there were a few shots left in his gun, and unless his hunters were creatures of the supernatural he could at least die fighting.

Still he fled, his feet landing hard now, every step jarring his whole frame. His arms flapped limply as he ran, and his steps were wider spaced as he staggered slightly. Trees appeared in his path as looming black shadows, and he swerved to avoid them. Would he ever see the lights of the village? He could have been running in a circle, for all he knew—there was neither moon nor stars in the sky, only the low scudding white snow clouds and that ghostly wind.

Then another tree sprang from the darkness at him, and his foot caught a root as he tried to turn. The forest spun around him, and the dirt smacked the side of his head. He tried to rise, but pain shot through his leg. Something wrong with his ankle—a break or a sprain, it didn't matter which now. He wasn't going to run any farther tonight.

He raised himself on his elbows and managed to drag his body to the base of the tree that had cost him his flight. He twisted around to a sitting position with his back to the trunk, and worked his pistol out. Seven shots left. Six for them, and one

Then he heard them. A snuffling sound in the darkness. The tree was large—they would have to come at him from the front. He braced the gun across his good knee and waited.

Section I: "What Have We To Do With Walking Corpses?"

Chapter 1: "Two Small Puncture Marks Where?"

Chapter 2: "What Does 'Vlkoslak' Mean?"

Chapter 3: "The Natives Believe Many Strange Things."

Chapter 4: "Well, It Looked Like A Huge Bat..." Section II: "Werewolves Can't Climb Trees."

Chapter 5: "Good Lord, Illya—What Was That?"

Chapter 6: "My Pets Seem To Be Restive Tonight."

Chapter 7: "Oh-oh, Here Comes Zoltan."

Chapter 8: "Begone, You Fiend Of Satan!" Section III: "Into The Darkness Where The Undead Wait."

Chapter 9: "The Only Way Out Is Through."

Chapter 10: "The Coffin Is Empty."

Chapter 11: "There Must Be A Logical, Rational Explanation."

Chapter 12: "You're Looking Inscrutable Again." Section IV: "The Vampire Has Been Dead Many Times...."

Chapter 13: "I Smell A Rat—A Rat With Feathers."

Chapter 14: "Only When I Am In Costume."

Chapter 15: "My Sense Of Humor Will Be The Death Of Me Yet."

Chapter 16: "He's Lying, Of Course."

Section I: "What Have We To Do With Walking Corpses?"

Chapter 1: "Two Small Puncture Marks Where?"

Routine communications enter the New York headquarters of the United Network Command for Law and Enforcement by teletype—and an amazing range of material is classified as "routine." Reports on the movements of suspicious individuals; queries for financial data on certain little-publicized companies; announcements of changes in personnel by recruitment, disconnection, retirement, or death; detailed descriptions of objects whose owners consider their very existence a well-kept secret; and complete, objective data on vast numbers of crimes ranging from loitering to attempted genocide. And it is a sad comment on the world of today that the most common crime so reported is murder.

Murder simple, in the heat of rage, with the nearest blunt instrument. Murder complex, with years of planning behind it and obscure Oriental poisons. Murder obvious, with a bullet hole in the back of the head. Murder subtle, with an important political figure collapsing of an apparent heart attack. And, occasionally, murder problematical, with a body found leaning against a tree in a forest in Rumania, as if he had sat down to rest—but a body with a greenstick fracture of the right ankle, an empty gun clenched in the right hand, and not a drop of blood in the veins.

* * *

Alexander Waverly, head of North American Operations for U.N.C.L.E., tossed the ragged-edged piece of yellow paper on his desk with a snort of disgust, and poked at his intercom. "What practical joker brought in this message purporting to be from Geneva?"

There was a momentary pause, and the voices answered uncertainly, "The packet was not tampered with between the message room and your hands, sir."

Waverly snorted. "All right. Give me Section Four."

His intercom hissed and clicked, and another voice said, "Communications—Carmichael."

"Waverly here. Who decoded the message from Geneva this morning? I'm interested specifically in section 23-5."

"I'll check, sir, but I believe I did."

"Please give the original ciphered text to the computer again, and bring it up with the results. I have found what appears to be a deciphering error, and I should like to be sure it will not happen again."

"Uh...right away, sir."

Waverly cut off the intercom and leaned back in his chair. I never enjoyed being an ogre, he thought. But sometimes it is best to throw a scare into a worker before he does something that could cause a great deal of trouble. He sighed, chose a pipe from the rack on his desk, and began to fill it from the humidor. When it was full he frowned at it as though he had forgotten what it was, then sat it down on his desk and began working through a set of reports from New Delhi.

A few minutes later his secretary announced Miss Carmichael, Section Four.

She carried two scrolls of yellow teletype paper, and advanced on Waverly's desk. "I re-ran the entire segment 23," she said without preamble. "Here is the text, just as it came off the machine." She emphasized the last phrase, defiantly.

Without a word, Waverly took the scroll and unrolled it. Part five...There it was.

"Regret to report death of Carl Endros, field agent from New York on temporary duty with Budapest office. On duty, routine investigation of rumors in rural area of central Rumania. No findings have been filed. Technician on assignment with him reports body found by peasants. Preliminary medical report indicates cause of death to be suicide complicated by complete hemospasia."

He looked up from the message to Miss Carmichael. "Have you read this?"

"I have scanned it for any obvious errors, sir."

Waverly extended his hand for the coded original. He couldn't sight-read the U.N.C.L.E. code as swiftly or as accurately as the computer, but he was able to supply his own approximate translation of the complexly garbled characters received from Geneva.

He studied the message for several seconds, then placed it on his desk and leaned back, puffing at his pipe, with an irritated expression. "Miss Carmichael, transmit a query to Geneva. Word it politely and don't give them the impression that I'm accusing them of anything, but find out who has been engaging in attempts at humor to the expense of our time and attention. If Geneva didn't originate the message, follow it back to Budapest and see if someone there has been nipping at the slivovitz during office hours. Carl Endros is a good agent, and inclined to be forgiving of practical jokes—but we cannot afford to be."

"Yes, sir. Shall I make this an official inquiry over your signature?"

"I don't...Yes." He leaned forward and took the pipe out of his mouth. "Put my signature on it. And when you find out who is responsible, put the matter before the head of our European section."

"Excuse me, sir...."

"Yes?"

"If the report should turn out not to be a joke?"

Waverly frowned. "If have a great deal of faith in Carl. If he had been shot, poisoned, blown up or impaled I should regret his loss. But the idea that he should commit suicide is patently ridiculous. If they think he did, get as much data as possible to me at once. And find out what the devil they mean by 'complete hemospasia.'"

Miss Carmichael nodded, swept up her original, and was gone. Alexander Waverly returned his attention to the reports on his desk.

* * *

Napoleon Solo's desk phone buzzed, and, as it had so many times before, the cool impersonal voice of Waverly's secretary invited him up to his superior's office. There was no hint of the type of invitation—it could be for a reprimand, a commendation, or a discussion of something interesting that had come up. Or it could be an assignment. He hoped so—he had been sitting around the office for almost a month, since returning from two busy months along the south coast of Spain keeping a misplaced H-bomb out of unfriendly hands and trying to get a glacially attractive countess into his own friendly hands.

The weather had been warm in Almeria, and the weather had been cool in New York when he had returned. But now it was the middle of April, and even the attractions of climate could not keep him from growing bored with more than three consecutive weeks of inaction. He had completed his income tax forms, read several books he'd been meaning to get around to, and studied all the reports from U.N.C.L.E. offices around the world that had come across his desk. He had worked out in the gymnasium and the target range, improving his armed and unarmed fighting, and had begun to practice with throwing knives. But he found it difficult to concentrate on anything without the pressure he was so used to in the field.

As he came out of his cubicle, he saw his partner, Illya Kuryakin, halfway up the hall ahead of him, going in the same direction, and hurried to catch him. Illya turned at the soft sound of a footstep.

"Ah, Napoleon. Did Mr. Waverly call you just now?"

Napoleon nodded. "We've been in drydock for three weeks, and I feel like I'm rusting away. Hope it's an assignment —

"Hey," he said, interrupting himself, "I learned a new one yesterday. Make like you're coming at me with a knife."

Illya dropped into a crouch, a pen from his shirt pocket gripped in his fist. He circled Napoleon warily, then feinted to the left and drove in from the right. Napoleon swung his left wrist across Illya's pushing the pen just enough off-course that it grazed his side harmlessly, and let his right palm come up against Illya's face, with the first and second fingers bent and resting lightly on the eyelids.

Illya recovered his balance. "Good," he said. "But if you could grab the wrist and pull forward, there would be additional force in the blow to the face. Also less opportunity for me to duck to one side and butt you in the stomach."

Napoleon grinned as they started off down the corridor again. "As a matter of fact, that's what I just unlearned. Trouble with the other way, it had both hands tied up. If you had a second knife, I'd be laid out like a mackerel. This way, my left hand is free..."

They continued talking shop as they made their way through the busy steel corridors of U.N.C.L.E. headquarters to Waverly's office. Napoleon remembered to straighten his tie and settle his coat more properly on his shoulders before they went in—Illya just ran a quick hand through his hair as the automatic door slid quietly open before them.

Inside, Waverly looked up from his desk with a black frown. There was a sheet of teletype paper before him, and without a word he picked it up and handed it across to them as they sat down. Napoleon took it and Illya read over his shoulder.

Carl Endros had been a casual acquaintance, one to whom they had nodded in the commissary, but he had also been an agent of U.N.C.L.E., just as they were, and his death came to remind them that either of them could have been in the same position. But the manner of his death

Napoleon looked up with a puzzled expression. "I can't see Carl killing himself. Have you checked with Section Six for his last physical and mental tests?"

"Yes," said Waverly shortly. "Checked out perfectly. Read on."

Napoleon did. Then his eyebrows came together. Then they rose. He looked up again. "It's two weeks late for April Fool's," he said.

"You are correct, Mr. Solo," said Waverly. "It is not a joke. Unless Carlo has taken leave of his senses and infected the rest of the European division with a grisly sense of humor." Carlo Amalfi was in Europe what Alexander Waverly was in North America. They had been personal friends for twenty years, and he was one of less than a dozen people in the world who called Waverly by his first name.

When Napoleon finished the report he looked up. "It sounds like he blew his brains out, all right," he admitted. "But what could have caused such a massive loss of blood the medical examiner would comment on it?"

"We don't know," said Waverly, staring idly at the bowl of his pipe. "It will be your job to find out."

"According to Eclary, the technician who found the body, there were no footprints in the soft dirt or in the snow around the body," said Illya, still studying the report. "He was shot at close range with his own pistol. Except for the fractured ankle, he appeared to be completely uninjured except for two small puncture marks at the base of the throat...." His voice trailed off.

Napoleon swiveled his head to look at his partner. "Two small puncture marks where?" he asked.

"At the base of the throat, it says. Right over the large vein. Oh yes, Eclary checked over the area and back-trailed him a short distance—says the footprints leading to the spot were running and irregular, and the post-mortem mentions evidence of extreme fatigue in the leg muscles."

"In other words," said Napoleon to no one in particular, "he ran until he couldn't run any longer, then sat down under a tree in the snow and shot himself. Then he lay there in a pool of blood until some peasants found him."

"Not quite," said Illya. "Eclary specifically mentions that there was no blood around the corpse. A little on the tree behind his head—that's all."

Napoleon didn't say anything. He looked at Waverly, then he looked at Illya. Then he took the paper from Illya's hand and read it all the way through again, carefully.

Finally he said, "After he shot himself, whatever was chasing him caught him. And where is this little village of Pokol?"

"Eclary's report was filed from the city of Brasov," said Illya. "That is just south of the center of Rumania, in the foothills of the Transylvanian Alps."

Napoleon looked closely at Illya. After a moment he said, "You're looking inscrutable. What are you thinking about the Transylvanian Alps?"

"Nothing in particular," said Illya slowly. "Just thinking. What does Transylvania suggest to you?"

Napoleon laughed. "Old movies. Bela Lugosi, werewolves, bad photography and melodramatic scripts."

"Has it ever occurred to you to wonder why they were always laid in Transylvania?"

"Now that you mention it, no. I suppose because the first one was."

"There are traditions in Rumania, Napoleon. Traditions and legends which..."

"Mr. Kuryakin!" Waverly's voice cut across between the two of them. "We are not dealing here with superstitious nonsense. We are dealing with the death of a very real agent of our organization. Unless you wish to request transfer to another assignment, you will be accompanying Mr. Solo to Pokol to investigate the circumstances surrounding this death. You are no more satisfied with the simple statement of suicide than I am. I suggest you make an attempt to keep your minds off nursery tales and things that go bump in the night, and concentrate on identifying the person or persons responsible for the murder of your co-worker. You will also want to clarify the circumstances surrounding his death in an attempt to arrive at an adequate explanation of the cause or causes. To this end," he continued, rummaging about in a drawer, "I have informed Budapest to expect you Friday afternoon. You will have all day tomorrow to pack and prepare." He came up with two envelopes and handed them across the table. "Here are your tickets. You will leave Kennedy International tomorrow night and change at Copenhagen."

He stared at Illya, then at Napoleon. "Unless you would rather let this assignment go by?"

"Oh, no," said Napoleon quickly. "I've had almost a month's vacation, and this sounds like it might be interesting."

"Yes, of course," said Illya. "The mountains are especially beautiful at this time of year."

"Very good," said Waverly. "There will be no further discussion of the folklore of the area."

"Yes, sir," they said together.

"If there are any more questions, they will be answered by the head of the Budapest office."

"Yes, sir," they said again, picked up their tickets, and left.

Once outside, they paused and looked at each other. At last Illya said, without looking at his partner, "I wonder whether a silver crucifix would be considered non-standard equipment?"

Napoleon stared at him with surprise. "Don't tell me you actually think that..."

"Of course not," said Illya quickly. "All the same, it wouldn't be any extra trouble to carry."

Napoleon laughed. "Oh, come on!" he said. "Next thing you'll be down in the armory asking them to run you up some cartridges with silver slugs in them."

Illya glanced sideways at his friend, and pursed his lips thoughtfully. "You know," he said, "that might not be a bad idea...." Then he sighed. "No, they'd only make snide remarks. And they'd want to know why. And then I'd have to tell them.... No, I guess it's not worth it."

"Okay," said Napoleon seriously. "If you want to bring a silver crucifix along, I promise not to kid you about it."

"I appreciate your consideration," Illya said thoughtfully.

"By the way," said Napoleon suddenly after a minute's silence, "do you think you could manage to make that two of them?"

Chapter 2: "What Does 'Vlkoslak' Mean?"

The flight was uneventful, except for the usual frustration of having only three hours between planes in Copenhagen—too long to sit around the airport, and not enough to go anywhere. Napoleon tried to call a couple of old friends, and found a girl named Gütte who had shared action with them over a year ago. She came out to Kastrup airport, bought them lunch, and kept their minds occupied with inconsequential chatter until the flight for Budapest left at noon.

At 4 o'clock their S-A-S jet thundered low over the outskirts of the Hungarian capital and landed them, if not behind the Iron Curtain, at least within one of its shallower folds. Passports and visas had been checked through the United Network Command office from Copenhagen, but as usual in this part of the world something had gone wrong.

Illya, fluent in Hungarian, attempted to deal with an official who held custody of the validating stamp, and who seemed to have an almost pathological fear of anything not covered explicitly in her book of regulations. Illya alternately bullied her and comforted her until she was completely confused, while Napoleon anxiously scanned the faces in the concourse for someone from the local branch of U.N.C.L.E.

With one ear he tried to follow the conversation between his partner and the clerk. Illya was saying, "My dear madame, we are (—something—) tourists who want (—something—) to see your beautiful country. Would you have us stand here three days and (—something—) the next airplane back to Copenhagen?"

Napoleon usually left the more guttural Slavic tongues to Illya, who possessed a native ability to pronounce interminable strings of consonants as if vowels were an unnecessary bourgeois luxury. Rumanian had enough in common with Italian, however, that Napoleon could make himself understood quite adequately, even if his accent left something to be desired.

A tall dark man with a long, mournful face came hurrying across the floor towards them, wallet in hand. As he came up to Napoleon the wallet popped open and a gold card caught the light. "Mr. Solo?" he said. Napoleon nodded. "I am Djelas Krepescu. Sorry for the delay—we had automotive trouble. Is there any difficulty here?"

He turned toward the counter, where Illya had stopped talking and was looking at him. He frowned at the clerk, whose eyebrows crept up her forehead, and spoke swiftly in Hungarian. Illya answered, and Krepescu said something to the clerk, emphasizing with a wave of his hand. She nodded vigorously and stamped the passports. She smiled apologetically at Napoleon, displaying a glittering row of metallic teeth, and said something to Illya about the noble gentlemen being very patient.

Once in the car, Djelas explained, "The clerk was being uncommonly difficult. She thought you were both Russian tourists, and there are many Hungarians who have no reason to love the Russians. As soon as I explained to her that you were Americans, and friends of mine, she was pleased to cooperate."

Napoleon glanced at Illya, who sat staring out a window, apparently lost in thought. It would be hard to explain to the poor woman how someone could be both Russian and American at the same time. "Well," he said, "we appreciate your help. We're going to need a lot more before we get out of here. Is everything cleared for us to fly to Bucharest this weekend?"

Djelas looked very sad. "The swiftness with which this has come upon us has made air reservations impossible to obtain. However, you can leave by rail Monday afternoon and arrive in Brasov Tuesday evening. It will be faster than waiting a week and flying to Bucharest, and then making rail connections from there."

Napoleon nodded. "It'll give us a better look at the country. I hear it's beautiful this time of year."

"Yes," said Djelas. "The air is rare and clear in the mountains, though it is quite cold."

Illya looked away from the passing view of the Andrassy Avenue and said, "What do you know about our reason for going to Brasov?"

The long face grew even longer. "The tragic death of Carl Endros. I met him only once, but I do not think such a man could kill himself unless something very wrong had happened to him. He was here for a few days on his way to Brasov about a month ago. We heard some strange things reported to our office in Bucharest, and Carl was interested to go and look them over."

"What sort of strange things?"

Djelas was hesitant. "Very strange things indeed—things which the peasants talk about among themselves and blow out of all proportion. We have the reports available for you to study. But please remember the facts are not known—all we have are rumors."

"What sort of rumors?" Illya persisted.

Djelas toyed with the end of his tie and looked about him. "As well as we can find, a pair of months ago or more or less, a body was found in the woods near the village of Pokol. Then, some few days later, another body. Both were dressed in peasant clothes, but neither was known to anyone in the area, and of course neither had any identification. Both were apparently killed the same way—very brutally. They were buried in the community cemetery at Pokol, with more ceremony than you would expect for total strangers."

Illya sighed. "And I suppose the bodies were both drained of blood?"

Djelas looked at the floor, and then out the window. At last he said, "I do not know of any medical report on the bodies. As I said, the peasants make up such stories and then expand them out of all proportion—"

"In other words, they were," said Napoleon.

"We don't know that," said Djelas quickly. "Under the circumstances we have begun proceedings to have the bodies exhumed and examined. All we know is that two bodies were found in the woods. The government is very sensitive about appearances..."

"And the whereabouts of all its citizens," muttered Illya.

"... and the fact of the bodies and the burials is quite well documented. But the rumors around them grew so prevalent that Mr. Endros went to Pokol to interview some of the witnesses. His one preliminary report was vague, but indicated he had traced the individuals who found the bodies. They swore to him that they had been bled dry."

Napoleon laughed. "Sounds like a psychotic killer in the village. A bit of detective work, Illya, and we can go home again."

"I hope so, Napoleon," said the Russian agent slowly. "I sincerely hope so."

* * *

They spent the next few hours reading over the reports that had been filed as referring to the finding of two unidentified bodies in the Transylvanian forests, and learned nothing. The rumors had placed the bodies at a dozen different spots in the mountains, from the Rosul Pass to the Prahova Valley; there were as few as two and as many as fifteen; they were all men, or men, women and children. But all the rumors agreed on the essential point—the manner of death.

Napoleon put the last sheet down and sighed. "Someone has gone to a great deal of trouble collecting all these," he said, indicating the sheaf of pages. "I'm sorry I don't appreciate them more."

Illya nodded. "We know nothing now that we didn't know four hours ago, and we have in addition received a great deal of confusing and contradictory data which is not only unnecessary, but a possible liability."

Napoleon chuckled. "You're starting to sound like Djelas. I think he learned English by memorizing a dictionary." He leaned back in his chair and stretched. "Well," he said, "now what? It looks to me like a plain case of murder. Some poor backwoods Rumanian has spun out, and killed two tramps in the woods. Carl was onto something, possibly went to his suspect, and got the same treatment. Now we go in, solve the puzzle, hand it over to the local police, who will proceed to take all the credit while thanking us privately, and then go home. I wonder if we could wrangle few days free in the area. There's a good ski resort at Poiana Brasov...."

"Possibly," said Illya. "Did you check with our host about accommodations for the weekend?"

"We can stay here. It's less trouble than trying to arrange for a hotel." He looked at his watch as a dark and pretty secretary came in and started gathering up the papers. "It's about eight o'clock, if I have my time zones straight. Is there any night life in this town?"

Illya looked surprised. "Napoleon, this is the capital city of Hungary. There is more night life here than in Madrid, Athens or Amsterdam. And I have never heard you complain about their quiet." He thought. "Dinner at the New York, and probably a show at the Budapest Night Club."