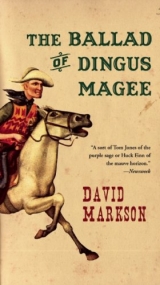

Текст книги "The Ballad of Dingus Magee"

Автор книги: David Markson

Жанр:

Современная проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 7 (всего у книги 11 страниц)

Dingus did not argue. He didn’t cave, even after what he had already lost. “All right,” he said, “never mind that. At least this time it’s straight stealing again anyways, upright reaching in and taking it, which puts you in a class with some better folks than the rest of my cousins. It’s almost a pleasure. But where’s Drucilla? That’s what I come back for anyways, not no piddling four hundred dollars or—”

“Ain’t heard, huh?” cousin Redburn asked.

“Heard what?”

“Well now, old Drucy, she done got married up with a lawyer feller.”

“She done what?With a who?”

“Yep. Right interesting story, too. You recollect that Comanche uprising here in town, back a while ago? Well, seems like what started it, it were some white feller diddling around with Comanche pussy, although as a matter of fact nobody could ever rightly learn that part of it too straight. But anyhow there was this one big buck was involved someway, and it seems he jest never did get over bearing a grudge. So even after the territorial governor declared a amnesty, this particular critter, he kept agitating troubles. Big foul-looking monstrosity, got a knife scar down one side of his face, and been shot in the shoulder once, likewise. And the ironic part was, he weren’t even married, but it appears what annoyed him was a white man carnal-ing jest any squaw a-tall. So anyways it turns out, he broods and broods back there on the reservation all this time, and then one day he comes riding on into town here, right smack down the main street bold as a fart in church. Couple of fellers like to shot him on sight, nacherly, but what with that there amnesty and all, well, they think twice about it. So meanwhile this here buck, by now he’s over to the main plaza, out front of the Fred Harvey Hotel it were, and the next thing you know, he’s sitting there crosslegged on the ground with his horse hobbled under a tree. Jest asittin’, is all, like maybe he’s resting a spell. He had a supply of jerkey with him, I reckon, or whatever all else it is them heathens eat, because the next thing after that, darned if’n he didn’t keep right on sitting there too, fer four whole days and nights. Weren’t nobody could figure out what he had in mind neither, except for watching folks contemptuous-like, and he sure done a heap of that, staring beady-eyed at anybody who went on by. Got to be a mite spooky after a time, sure enough, and some of the folks with shops down that way didn’t appreciate it nohow, since a right smart of the wives in town had already took to doing their purchasing elsewhere. So it’s likely he would of got shot after all, if’n he didn’t finally quit it. And by then we should of had some notion what he planned on doing, of course, seeing as how he hadn’t done it that anybody’d noticed before that, not once in the four days or nights. It must of been jest before dawn when he skedaddled, although nobody seen him go, but then the next morning it was like he was still sitting there anyhow, in a way, since folks had got so used to taking a nervous glance at him there still weren’t nobody could pass the spot without they looked over now also. Which must of been jest what he calculated on, in his scornful manner, because right there it stood, heaped up fer all to see and looking like there weren’t no human being in this world, and not even no redskinned one neither, could leave that much of a monument behind with jest one solitary dumping of his bowels—”

“Well hang it all,” Dingus demanded, “what do I care about that? What has that got to do with—”

“Well, I’m getting there, if’n you’ll be patient,” Redburn Horn declared. “Because it weren’t no more’n half a week later, and darned if’n he weren’t back again. This whole affair itself weren’t no more’n eight, ten days ago, incidentally. So anyhow this time the sheriff gets holt of him right quick, but now the Injun promises he won’t commit no more public nuisances. Because anyways he don’t intend to be here long enough for that, not this visit. Because this time what’s he do but parade right on into the courthouse and ask for a paper to be notarized. And not only is the paper writ in English, and by his own hand, but darned if’n he don’t talk the language better’n most native-born white folks, too. And what’s the paper, meantimes, but a draft on some Boston bank (or five thousand dollars,cash currency of the United States of America, and which the judge verifies for him likewise, and which he then takes on over to Zeke Burger’s clothing emporium and commences to buy clothes with. And not jest regular duds neither, like the usual calico shirt a ordinary Injun’d buy, but the absolutely fanciest stuff Zeke’s got in stock – like striped pants and what do you call them things, frock coats, and a gen-u-ine silk top hat to boot. And by this time there’s half the loafers in town looking through the window, of course, and after that when he walks on over to the stage office and asks for a ticket for as far north as you got to travel to catch a railroad train to Massachusetts, well now there’s not only the remaining half of the loafers but a good smart of the working folk in addition. And after this when it develops there ain’t no transportation until tomorrow, darned if’n the next thing he don’t do is march across to the hotel and request a place to sleep – and not jest no plain bedroom neither, mind you, even though the last time the polecat was in town he’d reposed under a cottonwood tree fer four consecutive nights, but he wants a whole durned sweet. Now old Phineas Austin back of the desk, he ain’t about to rent out no room or no sweet neither, not to no redskin, even if’n the redskin does happen to be outfitted like some Egyptian duke or something, but then the judge tells Phineas he better go ahead or else the Injun is apt to purchase the whole danged hotel and fire him. Because what happened is this. He were a full-blooded Comanche all right, but it seems when he was maybe nine years old he got lost one time, and hurt too, and some white folks in a passing stagecoach got holt of him – not only jest took care of him fer a spell, but finally even brung him all the way East and give him a education. Name’s White Eagle in Comanche, but it’s also Sidney Lowell Cabot Astor or some approximate thing in American, all plumb legal from where them Easterners eventually adopted him to boot. Evidendy he’d got restless after a spell, and had come back on out this-a-way, but now all of a sudden his foster father had caught the dropsy and died. Letter must of got to the reservation while he were in town here perpetrating that turdheap the week before, I reckon, but anyways he’d done inherited something akin to ten full street-blocks of downtown Boston, if not to mention a whole fleet of ocean-traveling boats, and some railroads, and the biggest law company in the state of Massachusetts. I forgot to mention that part, that he’d got educated in the law hisself. And that was when it came to pass with Drucilla, you see, when the judge happened to remark about that. Because I reckon you been away too long to know, but that Drucilla, why she jest had her heart set on marrying up with a lawyer feller, fer, oh, at least two or three months now, Dingus—”

That was something less than half a year ago. At first Dingus had been more confused than dismayed, but the confusion had stemmed from just the fact that there was no dismay. So it took him only a few days to realize that he had actually ceased to think about Drucilla a good while before. All he really cared about was that safe.

Nor was it the money either, the sixty or eighty thousand dollars which might surprise him by being considerably more than that. It was principle. Yet he did not rush back to it, on the premise that man cannot rush destiny anyway. Instead, he dropped hints and promoted rumors until some four thousand five hundred dollars in new rewards had accrued to his name. And even then he thought of this as mere exercise, as a sort of renewed apprenticeship before the ultimate, irreproachably professional enterprise of the safe itself.

But it amused him to wait, also, since it further enhanced the mood of anticipation. Deliberately he set out on a long, aimless journey into Old Mexico, where he had never been, to prolong it.

So then in Chihuahua he caught dysentery, a case so extreme that it not only postponed his return to Yerkey’s Hole for some months, but precluded mobility of any sort in the interim. “Less’n I want to leave a trail clear across the territory that even a old stuff-nosed mule-sniffer like Hoke Birdsill couldn’t miss,” he said.

Then, when he did return to New Mexico, the first thing he discovered was that the bounty on his head had mysteriously more than doubled, in major part because of a posting by something called the Fairweather Transportation Company, of which Dingus could have sworn he’d never heard. “But maybe I ought to get to it at that,” he decided, “ifn they even made it a criminal offense when I shit now.” He was some two weeks’ distance from Yerkey’s Hole when he picked up an innocuously moronic drifter named Turkey Doolan and headed west.

He had no attack in mind, only an abiding, bemused sense of confidence, as if the entire project were now less a matter of premeditation than of ordination, of fate itself. And even when Hoke Birdsill turned out to be as irascible as ever, not only banging Turkey Doolan from the saddle but wounding Dingus himself, Dingus remained merrily undaunted.

So he was still laughing, still delighted with the world he had merely put off conquering until tomorrow, when he took time out to deceive a drab, horse-faced woman named Agnes Pfeffer.

“Well, anyways,” he rationalized some few hours later, “at least it were a nostalgic sort of error, since I’m darned if’n she dint remind me jest a trifle of both Miss Grimshaw and Miss Youngblood theirselves.”

So it wasn’t Hoke Birdsill he was angry with tonight when he awoke in the bleak, familiar cell, of course, it was his own irresponsibility. Because he actually believed the conclusion he was to reach once Hoke left him alone to brood over his new incarceration. “That’s it, sure as outhouses draw flies,” he declared in resignation, fingering the swelling lump behind his ear. “A feller has to face life without a mother to guide him, he’s jest nacherly doomed to tickle the wrong titty, ‘times.”

Nor would there be any solution quite so simple as talking his way into a fake escape this time, Dingus knew. In fact Hoke seemed determined to give him no opportunity to talk about anything at all, since it had been well before ten o’clock when he departed, voicing his intention to look in on the indisposed Miss Pfeffer, and now at eleven there was still no sign of him. Although perhaps it was not quite eleven at that, since Dingus still made use of the old, engraved watch of his father’s which cousin Magee had given him, and it had long ago ceased to be reliable. “But jest the fact that I keep it proves I’m downright sentimental at heart,” he mused, “which shows all the more how I would of surely paid dutiful heed to a mother’s advice.”

Meanwhile the confinement had already begun to annoy him physically, albeit mainly because he was still unable to sit. He had dressed himself, once Hoke had removed the handcuffs, but he had been pacing restlessly ever since. On top of which it hurt where Hoke had bushwhacked him in Miss Pfeffer’s bed.

So he was still pacing when the woman, the squaw he had met earlier, came striding suddenly into the empty main room of the jail. And for a moment, preoccupied, Dingus did not even recognize her. Then he literally bounded toward the bars. Because she was still carrying his shotgun.

“Hey!” he cried, glancing to the door to make certain she was alone at the same time. “Howdy there! Remember me? From that there gun, when—”

But she ignored his interests completely, scowling in a preoccupation of her own. “Where that loose-button son-um-beetch?” she asked. “I decide never damn mind midnight, he marry up with me right now I think, hey?”

Dingus could scarcely recall what she was talking about, if he even fully knew. “Yeah, sure, anything you say,” he told her anxiously. “But lissen, that gun – it’s mine, remember? From out by that wagon, I give it to you. But it were only a loan, you understand? And now I need—”

She finally paused to consider him. “Oh, is you, hey? How you feel now, you still in bum shape? How come you in there anyways, yes?”

“Howdy, howdy, yair, I feel jest fine,” Dingus dismissed it, “but never mind that now, let’s—” She was holding the weapon inattentively, one finger through its trigger guard, and Dingus strained as if attempting to will her toward him. “Come on, now,” he pleaded. “I jest couldn’t carry it before, being hurt and such, but now I need it urgent again. Look, you got to—”

So then she was paying him no regard at all once more, clomping across to glance briefly into the back room, and then considering the desk. “He don’t come back here yet, hey? Not since I see him up there, suck round that pale-rump teacher-lady place?”

“Oh, look, look, I don’t know nothing about that—”

Dingus’ voice was rising, becoming mildly hysterical. “Ma’am – Miss Hot Water, ain’t that it? – look, please now, you jest got to give me that gun back. And before nobody else comes along neither, or it’ll be too – say, here, look, I’ll even buy it from you, I’ll give you…” He was fumbling anxiously in his pockets, then desperately. He had been carrying several silver dollars when he had undressed at Miss Pfeffer’s. His pockets were empty. “Oh, that unscrupulous, self-abusing old goat, even thieving from a unconscious prisoner, I’ll – aw, lady, please now, give me the—”

“You a pretty young feller be in hoosegow. What your names anyway, hey?”

“Dingus,” he sobbed absurdly. “Look, lady – ma’am – I jest got to have my—”

But Anna Hot Water was suddenly frowning, tilting her rhombic blunt head. “Dingus?” she said. She mouthed it slowly, in part with its common pronunciation but with overtones of the way it was enunciated by Indians or Mexicans. Then she said it again, wholly now in the second manner. “Dean Goose?”

Then something began to happen to Anna Hot Water. Her mouth was slack, and her eyes turned cloudy. For a long moment, while Dingus agonized over the shotgun, one arm actually stretching helplessly through the bars toward it now, stroking air, she seemed to be in agony herself, in an ordeal of what might have been attempted thought. Then he saw her begin to grasp it, whatever it was. Her eyes widened and widened.

“Dean Goose?” she repeated tentatively. “Feller stop one time up to Injun camp near Fronteras? Feller take on seventeen squaws in twenty hours nonstop and squish the belly-button out’n every damn one? Dean Goose? You thatDean Goose feller?”

“Well, yair now,” Dingus stated, “I reckon I been through Fronteras, but what’s—”

But he did not get to finish, because the rest of it happened so quickly then, and was so inexplicable, that for an instant he was totally at a loss. In fact for the first firaction of the instant he was terrified also, since he thought the shotgun was being aimed at himself. So he was actually leaping aside, sucking in what he believed might well be his last breath, when the gun roared, although by the time she had cast it away and flung the smashed cell door inward he had already realized, had understood that her aim had been true if still comprehending little else. Her face was radiant. She tore at her clothes.

“Dean Goose!” shecried. “Dean Goose for real, greatest bim-bam there is! Never mind that floppy-dong old Hoke Birdsill, oh you betcha! Come to Anna Hot Water, oh my Dean Goose lover!”

He felt his bandage tear loose as he vaulted Hoke’s desk. He had to sprint the width of the town before he was certain he had lost her.

He broke stride once, dodging behind Miss Pfeffer’s house to snatch up a fistful of the revolvers he had deposited there earlier, but she was still close enough behind him at that juncture that he had to leave his holster belts in the entangled sage, along with his Winchester. He ran on with the Colts clattering inside his shirt.

When he had finally drawn clear, he found that he had stopped not far from the dilapidated miners’ shacks he had seen before. In fact the lamp still burned in the one where he had come upon Brother Rowbottom, the dubious preacher. It took him time to catch his breath, especially since consideration of the manner of his deliverance had set him to laughing again, but eventually he limped back over there.

The man himself still sat amid the disheveled shacks as if having scarcely moved in the several hours except perhaps to raise the whiskey jug, which was wedged between his bony knees at the moment. He wore the same disreputable woolens, and the fight reflected dimly from his hairless lumpy skull. His empty left sleeve had become wound around his neck, draped there.

He did not appear thoroughly drunk, however, and he eyed Dingus quizzically. “So you come on back, eh? Heard the call of the Lord’s need after all, did you?”

“I were jest passing the vicinity,” Dingus replied. “IPn you’ll excuse the intrusion, I’ll make use out’n your lamp.” Not waiting for an answer (none was forthcoming anyway) Dingus set aside his weapons and then lowered his pants, twisting about to inspect the dressing. He had bled again, but not significantly. Watching him, or perhaps not, the man, Rowbottom, belched expressively.

“I reckon you’d better give me that damn dollar,” he decided then, as Dingus readjusted the bandage. “The Lord don’t cotton to critters repudiating His wants two times in the same night.”

But Dingus was not really listening. Because if he could afford to be safely amused again, it also struck him as time to turn serious about certain matters. “I reckon I’d best at that,” he told himself, “afore I wind up too pooped out for even simple stealing.” He fastened his belt, wondering if Hoke Birdsill had heard the shotgun.

“So do I get the lousy dollar or don’t I?” the preacher wanted to know.

Dingus reached absently into a pocket, then into a second one before recalling that Hoke had emptied them. But at the same time the first remote intimation of an idea was crossing his mind. He lifted his face to meet Rowbottom’s flat, oddly refractive eyes.

“You shy of cash money pretty bad, are you?” he asked then.

“The Lord’s work ain’t never terminated,” the man said.

“Tell you the truth now, I weren’t rightly thinking about His’n,” Dingus said, still pensive. “You got any sort of scheme in your head, maybe, about how a feller might go about getting a certain local business establishment empty of folks fer a brief spell? Like say a certain whorehouse – if’n you’ll pardon the term?”

“Women flesh runs a’rampant,” the man shrugged. “I been trying my best. But you drive ‘em out one door, they jest hies their abominations back through the nearest winder.”

But now Dingus was attending more to the tone of the man’s voice, its resonance, than to the content of his speech. “I dint mean preaching,” he explained. “You reckon folks’d hear you from a fair piece, if’n you had a sort of public announcement to make – say a announcement worth maybe twenty cash dollars?”

The preacher had been raising the jug. He dropped it as if struck. “Brother, leave us not bandy words. For twenty dollars cash currency I would hang by my only thumb at Calvary itself, hind side to.”

“Never mind getting no horse soldiers involved,” Dingus said. He retrieved the oldest of his Colts, hefting it momentarily. Then he tossed it pointedly onto the shuck mattress.

So then the preacher sat absolutely without movement, staring at the weapon, for perhaps ten seconds. “Fiftydollars,” he proclaimed finally. “The Lord couldn’t condone mayhem for less.”

“Ain’t mayhem neither,” Dingus said. “That there’s your pay. Twenty– twodollars, more like, standard saloon pawning price on the model.”

So the preacher inspected it then, trying the hammer gingerly several times. Then it disappeared all but miraculously beneath the shucks, as the man himself arose and stepped decisively toward the peg from which his clothes were hung. “The Lord’s will be done,” he intoned.

Dingus considered his antiquated watch as the man dressed. It was approximately eleven-thirty.

“Starting in jest about fifteen minutes from now,” he said, “all up and down the main street, but most especially up to Belle’s. Loud as you kin call it out, I want you to inform folks that Dingus Billy Magee done escaped jail again. And that he’s putting it to Hoke Birdsill to meet him fer a pistol shoot.” Dingus thought a moment. “Yair. Pronounce it fer out front of the jailhouse, at midnight sharp.”

Brother Rowbottom could not have been more unimpressed. “Feller name of Dingus Freddie Magee has got escaped again,” he repeated without emphasis, “and he hereby challenges Hoke Birdbelly to a fight with hoglegs, front of the jail come midnight. That the entirety of it?”

Dingus nodded, still contemplative. “But you pronounce it jest afore twelve up to Belle’s, that’s the crucial part. Folks’d be more interested in the chance they could see a bloody murder, than in jest some common everyday one-dollar poontang, don’t you reckon?”

“Ain’t mine to judge,” the preacher said. “The Lord sends me His missions in devious ways. You plumb sure I kin get twenty-two dollars on that Peacemaker single-action? Firing pin’s a mite wore, there.”

“You don’t,” Dingus said, “and somewhat later’n midnight I’ll give you payment for it myself – in dust gold or minted silver or paper currency or any other form you so desire.”

The preacher eyed him opaquely, buttoning a threadbare frock coat. Then he belched again.

“Amen,” Dingus said.

“So you’re a lamb of the Lord after all, eh?”

“Jest insofar as nature is concerned,” Dingus said. “Trees and clouds and such, sort of transcendental.”

So this time the preacher broke wind. “Emersonian horse pee,” he grunted.

But Dingus had already closed his eyes, leaning against the wall until he heard the man depart. Then, fingering the most recent bullet hole in his trustworthy vest, and with his young brow furrowed from the gravity of it all, he commenced to devise the remainder of his strategy.

“So even if’n I never had no mother at that,” he remarked aloud, “ain’t nobody gonter be able to say Dingus Billy Magee dint truly apply his talents in this life, after all.”

But certain sensuous remnants of the preacher’s flatulence were abruptly wafted toward him then, and he had to go hurriedly elsewhere.