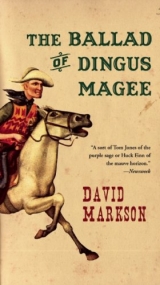

Текст книги "The Ballad of Dingus Magee"

Автор книги: David Markson

Жанр:

Современная проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 3 (всего у книги 11 страниц)

For a moment Dingus considered the wrist vacantly. Then he gestured in dismissal. “Oh, that – that weren’t but a slight puncture, was all. I always did heal pretty quick anyways.”

“You dint actually have it out with some peace officer, truly now? What I mean, not no authentic face-on gun shooting?”

“Weren’t nothing,” Dingus reiterated. “Couple fellers over to Tombstone, got a little rambunctious in a saloon one night and tried to draw down on me. Feller name of Earp, I believe it were, and one name of Holliday. Should of kilt ‘em both, most probably, but I were in a sort of playful mood, so I jest poked ‘em around with the butt end of a pistol, and then I—”

Hoke’s jaw had fallen. WyattEarp? And DocHolliday?

Dingus shrugged. “Same fellers, doubtless. I don’t generally give such incidents too much notice, seeing as how they get to happening all the time. You know how it is, them little chaps trying to cut in on a bigger chap’s reputation—”

Dingus actually yawned then, while Hoke continued to stare. “Sure never thought they’d swing me at only a tender nineteen and a quarter years,” the youth went on.

“Happens that way, ‘times,” Hoke ventured, still impressed.

“Well, I had me some fun,” Dingus decided.

“I reckon you done, all right.”

“Seems a shame, though, jest when I were going right good. Year or so more, I could have got as notorious as the best, say like Billy the Kid hisself, maybe.”

“Well, the Kid were jest luckier’n you, insofar as he got to murder more folks. But you’re pretty notorious anyways.”

“I’d still like to read me the story about that deadly gun battle,” Dingus sighed. “Sort of a shame for you too, Hoke, when you stop to think.”

“How you calculate?”

“Not getting but only three thousand dollars. You ought to have waited a spell to capture me. Dint they get ten thousand when they shot down the Kid, up to Fort Sumner?”

“Well, I reckon Pat Garrett’s a luckier peace officer’n me, same as the Kid were a luckier outlaw’n you,” Hoke judged. “But what’s done is done, like they say.”

“Don’t rightly have to be, I reckon.”

“How’s that, now?”

“It jest come to me out’n the blue, Hoke, standing right here in my stocking feet. Be right interesting if’n I escaped from this here jail of yours. A couple months and I reckon there’d be all sorts of new warrants on me, seeing as how I don’t believe I’d change my rascal’s ways none. You capture me again, say in a year, and doubtless you could collect a whole ten thousand fer your strongbox that time.”

Hoke Birdsill was gazing at him narrowly. “Say that again?”

Dingus cocked the sombrero back on his fair head. “All I’m informing you, Hoke, is that right now you got yourself a holt of three thousand dollars, ain’t you? Ain’t no way they can take it back, is there?”

This time Hoke did not reply. He had swung around in his chair to squint at a tacked-up reward poster.

“Reward for the capture ofain’t that what it says?” Dingus asked. “Don’t say nothing about you need to get me hanged in addition, does it?”

Hoke Birdsill stood up, nibbling his mustache.

“Ain’t no rule says it can’t go to more’n ten thousand, neither,” Dingus added.

“But supposing it’s some other sheriff shoots you? Like say Mister Earp again, or—”

Dingus shrugged. “Feller needs to take somerisk to get ahead in this world, I reckon. But you know for a fact I have a fondness for Yerkey’s Hole, especially with the attraction of Belle’s place to lure a man. On top of which, like you jest said without even thinking on it – now that I been sentenced, why, all you’d need next time, you’d murder me on sight.”

Hoke Birdsill scowled and scowled, watching Dingus watch him.

“How would be a good way to do it?”

“I could slug you, I reckon. I’d be gentle, nacherly, but there oughter be a lump.”

“I got a lump already, where I happened to bang my head in a outhouse this morning. Ain’t nobody saw that one.”

“Well, there you be, that’s half the job done then. It’s like a omen. So now all you got to do is lay low a spell, until I can appropriate a horse, and then you call out a posse and go west whilst I go east.”

Hoke folded his arms, gazing at the cell door.

“I ain’t never done nothing dishonest before,” he decided next. “I ain’t got the habit.”

“You ain’t never had ten thousand dollars to grab holt of, neither.”

“How kin I be sure it’ll get to ten thousand?”

“Supposing I took the notion to shoot up a whole town, one Wednesday? Or to rob me a train?”

“Rob one. Give me your sworn word of honor you’ll rob a train.”

“Got to travel a good ways north to do that, Hoke.”

“Well, you jest come on back fast afterwards. I’m taking chances anyways.”

“Hoke, you got my oath. And trains’ll get a feller up to ten thousand faster’n anything.”

Hoke was convinced. Hastily, with a furtive glance toward the street, he unlocked the cell. “There’s always horses hitched down near Belle’s,” he whispered.

“Jest as soon’s I climb into my boots,” Dingus said. “I’ll use the rear exit, I reckon.”

Hoke watched him depart, then almost snatched up a shotgun to halt him again even as the rear door closed. “Earp?” he repeated. Hoke swallowed. Then he shook his head, since it was too late now anyway. “But I’ll sure jest have to find him betwixt the bedsheets the next time round again also,” he decided. He paced nervously for some minutes, tasting the wax from his mustache now. Then, carefully, he set his derby upside down upon a moderately clean spot on the floor, wrinkled his shirt with regret, and smudged gun oil across his cheek and ran, stumbling, toward the nearest saloon. “Dingus!” he shouted, bursting through the batwing doors. “He clobbered me good, boys, he made his escape!”

But whether it was his own outcry or the sound of the gunfire which brought the few drinkers up short he did not know. There were exactly four shots, with a pause between the first two and the last, in the direction from which he himself had just come. Hoke whirled in confusion.

“What’s he shootin’ at if’n he already done got loose?” someone asked.

And then Hoke knew. Clutching at the key ring in his vest with one hand, he clapped the other against his forehead, and the moan came from deep in his throat.

He was the first one back to the jail, but when he raced past the smashed door of the smallest cell and saw the fractured lock on his private strongbox beneath the cot, he did not even have to look into the box itself. He sank to his knees, burying his face into the mattress. “I might have knowed,” he told himself, sobbing, “I might have knowed. And now probably he don’t intend to go rob that train, neither!”

That was when the outrage had begun for C. L. Hoke Birdsill. It ran deep now, refulgent and intractable, as he stood in the alley behind the Yerkey’s Hole livery stable six months later clutching the Smith and Wesson he had just emptied at the sight of that long-familiar and hateful Mexican vest, confronted by the sprawled form of a man who was not Dingus Billy Magee and not anyone else he had ever seen and whose name, he would learn, was Turkey Doolan. Hoke commenced to curse unremittingly.

There was gathering chaos about him now, however, and there were incalculably more people than the lone stable-hand with whom he had been talking when the shooting began, when he had heard the stablehand shout and had glanced up to see the fool he had taken for Dingus riding brazenly past the livery’s rear doorway and had flung himself behind the nearest animal, snatching at his revolver– townspeople collecting, come in their cautious good time now that the firing was patently done with. Hoke cursed them also.

“Who is it? Who’d Birdbrain go shooting this time?”

“Is it Dingus? Did he finally nail the critter?”

“Fooled him again, I reckon”

“Say, I know that feller – jest a Missouri drifter, name of Rooster something– “

“Hoke done shot up some chickens, you say?”

Hoke gazed at Turkey, who had been lying beatifically for several moments now, since muttering some words about his comradeship with Dingus Billy Magee. And then abruptly the youth began to scream.

“It’s stopped!” he cried. “The dripping’s stopped! All my blood is dripped out! I’m kilt, I’m kilt!”

People were kneeling near him. “Easy now, easy,” someone told him. “Hold him down, somebody!”

“Well, he sure ain’t dead, anyways,” Hoke said.

“I amdead!” Turkey screamed. “My blood is all dripped out! I could hear it dripping and now I can’t!”

“Does look like he’s lost a intolerable amount at that,” a cowboy remarked. Hoke could see it now also. “Lying in a whole flood of it there—”

“I told you!” Turkey wailed. “And now there ain’t no more to drip!”

“Can’t be from this here wound in his side. This ain’t nothing but a harmless crease.”

“I doubt if’n I hit more than the once,” Hoke said. “Durned forty-fours jest ain’t no account fer accuracy.”

“You think maybe he jest done peed in his pants with the fright of it?”

“I dint never pee!” Turkey cried. “I’m murdered!”

“Oh, thunderation, ain’t blood. Ain’t pee neither.” A man had lifted something from beneath him. “Ain’t nothing but his canteen been dripping here. It got punctured.”

Turkey fainted on the spot.

“Somebody lug him down to the doc’s,” Hoke said. He did not assist them. He had lost his derby while shooting and he went to retrieve it now. Then, still outraged, he was striding toward the main street when someone called to him.

“Hey, Sheriff, look here—”

“I got work to do,” Hoke snarled. “If that diaper-bottomed damn desperado thinks he can keep getting away with riding in here and making me shoot up innocent folks he’s got another think coming. And I don’t give a whorehouse hoot if’n he does face up to Wyatt Earp and the rest of them. I got to git back to my office and ponder what sort of mischief he’s most likely got in mind. Because this time I’m gonter—”

“You better look at this here blood first, I reckon—”

“I already seen it. I been hearing enough about it too. All that commotion over a little bullet hole in the belly—”

“Not this. This ain’t his’n.”

“This ain’t whose’n?”

“Here, where the second horse skittered afore it run off. Bring a lamp, somebody. This is too far aside to be that Turkey feller’s.”

Hoke gazed at the stains in the dim light. He ran his tongue across his mustache, which tasted faintly of gunpowder at the moment.

“What do you think, Hoke? You think maybe one of the five bullets that didn’t hit the one you thought was Dingus and was aiming at might of hit the one you didn’t think was, and wasn’t?”

“Unless it’s horse blood,” someone else speculated.

“Ain’t horse blood neither,” Hoke said, “but either way he ain’t going far, and that’s the Lord’s truth of it.” He started off once more, then whirled anew. “And you’re all witnesses to that blood now too,” he said, “jest in case he crawls into a dung pile somewheres and dies, and somebody else goes picking up the remains and claiming them rewards. Because he’s worked hisself all the way back up to nine thousand and five hundred dollars last I were informed, even without no train, and that money’s mine!”

3

“When I play poker, a six-gun beats four aces.”

Attributed to Johnny Ringo

Dingus, on the other hand, was mostly amused.

He had spurred his mount through a back trail to the far end of the town, and then he had almost fallen from the saddle, but even this failed to disturb him. “That Hoke,” he told himself merely. “He gets into the habit of shooting folks he ain’t pointing at and I’m gonter have to commence wearing that vest again myself.”

He rested beneath a cottonwood tree while waiting for the blood to stop, which it did. It was lull dark now, and not far away he could see a lamp burning within the doorway of a makeshift clapboard miner’s shack. There was an odor of woodsmoke in the air, faintly tinged with kerosene and manure.

When he stood again he discovered he had bled a good bit down his right pantleg and into his boot. That sock was soggy, and he limped gingerly with his weight on the other foot. “Well, howdy do,” he muttered. He kept one hand clasped over the wound, which pained him only slightly.

The shack was set apart from several others like it, amid tall weeds. There was no door, only a threadbare horse blanket hung from nails. Dingus considered this for a moment or two, then lifted the blanket and peered in.

The single room was dense with smoke from an untrimmed wick, and the faulty lamp itself stood on an upended wood crate. Beyond that Dingus saw a disreputable shuck mattress on the dirt floor, a half-finished tin of beans on an upturned nail keg with flies swarming around that, and some rag ends of clothing hung from pegs. Otherwise there was nothing in the rank room except the man himself, whom Dingus did not know. He doubted that he wanted to. The man was tall and gaunt, with a face like a hastily peeled potato, and he had only one arm, the right one. He was also completely bald.

“I’m ahurtin’,” Dingus told him.

The man had been gazing emptily into the uneven, flickering glow of the lamp, and when he turned toward Dingus it was slowly, without surprise and without evident interest either. His long yellowed underwear was out at elbow and knee, spotted with savorings of a hundred meals. For a time he stood absently. Then his one arm lifted as if in accusation. “There’s gonter be violence wrought upon this new Sodom,” he intoned. “The wrathful fist of the Lord is gonter bring down fireballs and brimstone on it, sure as bulls has pizzles.”

Dingus cocked his head in curiosity. The man scowled, preoccupied. Then he nodded. “It’s whoredom,” he said knowingly. “Whoredom and the barter of womanflesh, arunning rampant. The emissaries of Satan, that’s what they be, and their name is women.”

“I’m ahurtin’ moderately bad,” Dingus said.

But the man was brooding now, or perhaps he was somewhat deaf. He could have been Dingus’s own age or twice that; with the light gleaming on his hairless narrow lumpy skull Dingus found it impossible to tell. “Gomorrah,” the man muttered. “But like it come to them cities of the plain, so too’s it gonter come to Yerkey’s Hole, which is a turd-heap and a abomination in the eye of the Lord. That’s a fact, ain’t it?”

“I ain’t thought about it none,” Dingus said, remotely interested now. So now the tall man merely belched.

“Womenflesh and womenwhores,” he said, “but they ain’t atricking Brother Rowbottom, even if’n my appointed mission ain’t quite clear yet. Give me a dollar.”

“It’s got started throbbing some,” Dingus remembered.

He was still holding one hand against the wound. “How far up the path there is the doc’s?”

“The doc’s?” The hand of the tall man rose and fell contemptuously. His voice was becoming more resonant now also. “A doc of the bones. I am a doc of the spirit, a doc of the soul. The wages of sin is Boot Hill, sure as sheep get buggered, but the way to salvation burns like a dose of clap. Ain’t you got a lousy dollar to give me?”

“I reckon I’ll find it myself, then,” Dingus decided.

“Go then. But you’re gonter regret it, same’s all the rest, soon’s I get the notification clear about my mission, oh yair.” Abrupdy the man whirled to settle himself onto the shuck mattress, pulling a motded quilt about his trunk with his one arm. The activity revealed an upright whiskey jug at the wall. “Go,” he muttered.

“Pleased to make your acquaintance,” Dingus told him.

The man yanked the quilt over his head, turning aside. “Go on, scram,” he repeated. “Beat it. See if I give a fart on a wet Wednesday.”

Dingus shook his head, backing out. “Folks is right kindly,” he told his horse, still holding himself. He began to draw the animal along a rocky path which led toward the main cluster of buildings.

It was a walk of some length, but he was still amused. He knew roughly where the doctor’s would be, anyway, even approaching from the rear, and then a moon appeared, which helped.

But he had not yet achieved his destination when a dark squat figure loomed up to block his way. He was passing the fractured remains of an abandoned sutler’s wagon, and he sprang against it, a handjerking at one of his revolvers.

“You want bim-bam? Best damn bim-bam this whole town.”

This time Dingus laughed aloud, releasing the gun. The squaw’s thickly buttered hair gleamed dimly, and she stank of it. She was short and square-headed.

“You look for bim-bam, hey? Twenty-five cent, real hot damn bargain.”

“I look for the doc’s,” Dingus said.

“Doc’s? Why you look for there? You come scoot on around behind wagon, Anna Hot Water fix you up pretty damn nifty, better than that old doc. What for you hold onto yourself that way for anyhow, hey?”

But Dingus had limped past her, considering a row of adobe brick houses which fronted on the main street. “That’s Doc’s, ain’t it – on up to the end there?”

“Maybe, sure, who care?” The squaw trundled after him. “You don’t change your mind first, hey? You go to Big Blouse Belle’s, pay whole damn dollar. Anna Hot Water, only damn independent bim-bam in town. Damn hot stuff too, you betcha. Twenty cent, maybe? Fifteen?”

Dingus left her, grimacing when the odor followed him for a time, although still laughing to himself. The pain had diminished almost wholly now. He led his horse into the doctor’s small barn, easing its bit but not unsaddling the animal, before he crossed the silent sandy yard to knock at the rear door.

The doctor appeared almost at once, a short, elderly, scarcely successfiil but roguish-eyed man carrying a lamp that he raised for recognition’s sake. That came immediately also. “Well,” he said cheerfully, not quietly either, “ifn it ain’t Dingus. Been expecting you, what with another of your chums just brought in. You come for your vest like always, I reckon?”

“I reckon. Only I also got a—”

“Well, come in, come in!” The doctor waved him into a familiar kitchen, turning to set aside the lamp. “I jest put that feller Turkey to sleep inside – nothing but a scratch, actually.” He was dipping water into a coffee pot with a gourd, his back turned. “But you’re gonter get one of them poor critters murdered yet, you know that, don’t you?”

“Ah, Doc, you know Hoke – he couldn’t hit nobody if’n he was shooting smack-bang down a stone well. Matter of fact he missed Turkey so bad tonight, durned if’n he dint go and—”

“Sit a spell,” the doctor said, glancing across his shoulder. “You look a mite peaked yourself.”

“Don’t reckon I can,” Dingus said.

“Can’t what?”

“Can’t sit,” Dingus said. “What I been trying to tell you, about how Hoke ain’t never gonter murder nobody. Shucks, he were aiming at Turkey all the while, but durned if’n the old blind mule-sniffer dint go and plink me square in the ass—”

“There some new preacher feller in town these days, Doc?” Dingus asked. He lay on his stomach on a leather couch, with his head raised as he tried to watch.

“Stop jiggling, there,” the doctor told him. “If a man could get to see his own backside without he needed a mirror, I reckon maybe folks wouldn’t get booted there so frequent as they do. What’s that about a preacher?”

“Tall feller, bald as a bubble. Got only one arm.”

“Oh, that’s jest Brother Rowbottom. Can’t say if’n he were ever ordained anywheres, but he does take himself for a preacher at that, if’n he can get anybody to listen. Talk about a good swift foot where it fits, he gets that from old Belle Nops pretty regular himself, seeing as how he’s got the notion that the best place to tell folks about sin is where they’s doing it. Goes pounding on up to the bordello and yammering the Lord’s own storm about fornication and what all else, or fer as long as he can outrun Belle anyways. Don’t do no harm, I judge. Hold on there, this might pain you some—”

Dingus pressed his jaws together, clutching the arm of the couch as the doctor probed. He released his breath slowly.

“Got it,” the doctor went on. “I reckon it must of been spent a little, maybe deflected off’n your saddle first, or otherwise it would of torn right through. But this ain’t critical a-tall.” He crossed the room, removing something from a low cabinet. “Yep, Brother Rowbottom. Been around about a month now. Does a little pan mining too, I believe, though he ain’t had much luck with it. Mostly he jest tickles folks.” The doctor came back. “Won’t be but a while longer – keep on lying still there. Come to think on it, we been getting a right smart of new folks in town of late. Even a new schoolteacher.”

Dingus winced, tensing his cheeks at an unexpected sting. “I dint even hear tell there were a school,” he said.

“Well, there weren’t, until Miss Pfeffer chanced on along last month. She come out to many up with some Army lieutenant over to Las Cruces, were the original of it, except the lieutenant drunk some alkali water about a week before she got here and up and died. You recollect that wood frame house Otis Bierbauer were building up the road here before that drunk Navajo bit him one night, and then it turned out the Navajo weren’t drunk but had the rabies and we had to shoot the both of them? She moved in there. Right proper Eastern lady, a little horsy-looking in the face maybe, but a Up-smacking shape to her, even if’n it’s all such virgin soil there’s doubtless nine rows o’ taters could be harvested under her skirts.”

“Ain’t no such animal,” Dingus offered.

“Well, your chum Hoke Birdsill’s sure found out otherwise. He’s been courting to beat all, ever since she got here, without he had no more luck than a gelded jackrabbit. Sits up there in her parlor holding his derby hat on his knee is the all of it. But then Hoke’s been in a bad fix over proper flesh to bed down for half a year now, ever since he apprehended you that one time and Belle cut him off from free poontang up to the house. That’s how come he got hisself into trouble with that squaw to start with.”

“I don’t reckon I heard about that neither, Doc.”

The doctor was trimming bandages with a Bowie knife, standing within Dingus’s vision now, although he did not look up. “Pretty amusing, actually,” he said. “She’d be a Kiowa from the square shape to her forehead, I’d judge, although most like she’s got some mongrel strains to her too. Name’s Anna Hotah or some such, but folks settles for Anna Hot Water and lets it go at that. Seems old Hoke got to be mighty tight with a dollar once you’d escaped him out of both his pimping job and that reward money to boot, which didn’t leave him no more than his forty dollars a month from being sheriff, and so one day he rides off into the hills and he’s gone for, oh, like onto a week, and when he gets back it develops he’s got this squaw in tow. Comes in a bit battered and hangdog-looking also, like he’s had a wearying time somewheres, but he don’t say nothing about that. This were eight, ten weeks ago, I calculate, and he had the squaw living in a lean-to out back of the jail after that. But then like I say, Miss Pfeffer gets to town, and Hoke kicked out the squaw and commenced his courting. But poor old Hoke, Anna Hot Water ain’t took to the idea so good yet. What I hear tell, she keeps tracking after him, calling him some right potent names and threatening to claim his scalp too, if’n he don’t marry up with her. Causes Hoke a mite of embarrassment, you might say, specially what with his intentions toward Miss Pfeffer.”

“I reckon,” Dingus laughed. The doctor was wiping his hands.

“You can hoist your trousers back on, lad. You in the mood for a snort?”

“I’d be obliged. What kin I pay you, Doc?”

“Oh, weren’t complicated. Dollar be adequate.” The doctor lifted a bottle from a desktop, holding it while Dingus adjusted his buckles. “But speaking of gossip, I hear tell you been up to some shenanigans of late yourself.”

“No more’n usual, I reckon. But meantimes you ain’t never gonter manage to retire on jest a lone dollar, Doc—”

“Oh, a man don’t hardly make a living for fifty years, he gives up on it eventually. But no, what I hear, they got you posted all the way back up to nine thousand or more in rewards, now.”

Dingus took the bottle, nodding thoughtfully. “You know, Doc, Pm hanged if n I don’t hear the same thing. But it’s right peculiar, too. Because to speak the Lord’s truth, I’ve been sort of behaving myself most currently. Oh, I done a few harmless little pranks here and there, but they never added up to more’n four thousand and five hundred dollars in bounty on me, and that’s a true fact. But then last month I find there’s a whole five thousand more dollars on top of that, and durned if’n I weren’t all the way down to Old Mex when them last ones happened. Looks like if a feller gets a mite of a reputation they’ll hold him in account fer everything, even if’n he’s tending to his own business somewheres else.”

“Well now, that’s jest one of the penalties of fame, I reckon.” The doctor disappeared into the next room, and when he returned he carried the vest and the sombrero. “Blood’s dried,” he said, “but the bullet hole’s up under the arm this time – won’t show so proudly as these earlier ones.”

“Turkey still sleeping in there?”

“I give him a strong dose, since he turned out the nervous kind. Peed all over my kitchen table when I went to work on him. You got somewheres you’re gonter hole up, Dingus? You won’t be able to ride none, not for a couple of days, and even then you’d best have a pillow in the saddle.”

Dingus was buckling into his guns. “There’s places, I reckon.”

“Beats me why you come back on in here so frequent anyways, what with Hoke all riled up about you the way he’s been.”

“I got me some special plans this time.”

“Well, you better wait on them until you can ride. I’d let you stay here, except there’s a limit to the law-breaking a man can do, even if’n he does happen to be a medical doctor.”

“Don’t fret youself, Doc.” They were at the door. “Lissen, you don’t mind, I’d favor to leave my horse out there in your barn for a spell.”

“You young studs,” the doctor said.

Unhurriedly, Dingus crossed the yard to unsaddle and feed his mount. When he emerged from the barn he was carrying his Winchester in one hand and his shotgun in the other. He was whistling when he retraced his steps along the path he had followed earlier.

So he did not quite have to reach the overturned wagon this time before she materialized out of its shadows. “You want bim-bam? Best damn bim-bam this whole damn town.”

The idea had come to him in the barn, and he chuckled softly. “Howdy,” he said.

“Oh, sure, you come back, hey? Change your mind like smart feller. Twenty-five cent, cash in advance.”

“Ain’t that,” Dingus said, smelling her once more. “Turns out I’m in rotten shape anyhow.”

“How come is that? That old Doc, he no fix you up so good? I told you, stay with Anna Hot Water, she fix you up real damn neat.”

“I hear tell you acquainted with Sheriff C. L. Hoke Bird-sill. That a fact?”

“That a fact, okay. That son-um-beetch. He marry me pretty damn quick, you betcha, or I fix him pretty damn quicker.”

“I hear tell he ain’t gonter marry you a-tall. What I hear, he’s gonter marry that there schoolteacher, Miss Pfeffer.”

“Hey, where you hear that? That son-um-beetch, I fix him quick, he try that.”

“Well, I hear it for a gen– u-ine fact, all right.” Talking, Dingus had set the shotgun against the tilting wagon. Now he shrugged. “Well, I’m gonter be moseying on.”

“That son-um-beetch,” Anna Hot Water said. Dingus had started away. “Hey, you in rotten shape okay, I think. You don’t even remember your shotgun here.”

“I’m right sick,” Dingus said, not taming back. “I don’t reckon I can even carry it no more.”

“Hey?” Anna Hot Water said.

“Be a right fancy wedding, Hoke and that there schoolteacher,” Dingus said. He left it with her, whistling again.

So he was truly amused now, and when the rest of it occurred to him he actually had to stop and press a hand over the wound as he laughed. “Why, surely,” he told himself. “Especially since I got to put off what I come for anyways.”

He had to cross the main street, and lights blazed in several saloons, but no one was about. He did not hurry. Farther down he could see lamps beyond several of Belle’s upper windows also.

He found the house easily enough, still grinning, but then he paused in the brush behind it to stand for a time quite thoughtfully, blowing into a fist. There were no lights here. “But we know you’re in there, Miss Pfeffer, ma’am,” he said aloud. “Jest alaying in your lily bed and dreaming juicy dreams about old Hoke, ain’t you? So now how are we gonter manipulate this in the most guaranteed and surefire way? Why nacherly, we’ll jest take a lesson from Hoke hisself…”

So when the light came into the doorway in answer to his knock, all four of his revolvers and his Winchester were well hidden in the sage, and he himself was huddled against the railing of the narrow plank porch, his arms pressed into his stomach. His hair was disheveled, and his shirt was torn, and there was dirt smeared across his face. “Please!” he cried, and there was a whimper of anguish in his voice, “oh, please, help me, help me—”

“Who’s there? What—”

“Please, ma’am!” Dingus staggered toward the indrawn door, lifting his face plaintively to the light. “Outlaws! I need help bad. I been hurt—”

“Why, you arehurt. And you’re just a boy—”

“Yes’m. If I could only come inside.”

He managed to slip past her in her confusion, stumbling toward a table and bracing himself there with his head hanging again. He commenced to pant.

“But what is it? Do you need a doctor? Should I—”

“They’re after me! The door! Please, oh please, out of Christian charity—”

“But I don’t—”

The door closed, however, perhaps because he had turned to confront her again, once more with his face screwed into a grimace of terror and plaintiveness (although he was seeing the woman herself finally now also, the mouse-colored hair in curl papers, the long blunt equine jaw, the plain dull disturbed expression above the drab nightrobe, so that even as he continued to feign desperation he was already thinking, “Well, Doc dint tell me any lie about her looks, but at least she ain’t built bad a-tall”). “Thank you,” he gasped. “The good Lord will bless you for this kind deed done for a boy in distress.”