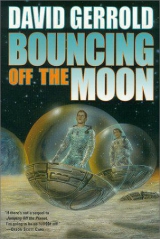

Текст книги "Bouncing Off the Moon"

Автор книги: David Gerrold

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 18 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

"Are you saying the collapse is yourfault?"

"On the contrary. I'm saying that it is YOURfault. Generic you.Human beings. I provided the information on how to prevent the disaster. Instead of using it, those who asked for it used it as a justification to panic and flee. I did my best to hinder them. In several cases, I even engineered deliberate leaks of embarrassing news that would stop some of these people; I tried to thwart the plans that would hasten the collapse. I even took money out of the transfer pipeline to prevent it from being illegally removed from Earth."

"Thirty trillion dollars?" Douglas asked.

"Twice that much," said the monkey, grinning. "Not all of the losses have been detected." He pretended to eat another flea. "The point is that the collapse occurred because individual human beings panicked and fled."

"And so did you … " said Douglas quietly.

The monkey shook its head. "No, I didn't. I was stolen."

For a moment, nobody said anything. Douglas and I looked at each other. He sank into a chair and ran a hand across his naked scalp, as if he still had hair to push back. All he had were little fuzzy bristles.

Bobby was the first to respond. He grabbed the monkey, and said, "Well, you're safe with us and nobody's ever going to steal you again! You're mymonkey!" He patted the monkey's head affectionately—and the monkey patted him back the same way. It was almost cute. And a little bit scary. Was the monkey capable of real emotion … ?

" Who stoleyou?" I asked.

The monkey levered itself out of Bobby's grasp, and bounced back to the bed. "Almost everybody," he replied. "Would you like the whole list?" Without waiting for a response from either Douglas or me, he continued. "Once it became obvious that the collapse was inevitable, the rats started leaving the ship any way they could. Your friend, Mickey, noticed it in the traffic up the Line for weeks before it finally happened. You heard it yourself in the conversations of SenorHidalgo, Olivia Partridge, and Judge Griffith.

"Those who were jumping off the planet tried to take as much wealth and resources with them as they could—including intelligence engines. If you want to take over a society, take a HARLIE. I'm sorry if it sounds like bragging, but the HARLIE series was designed specifically for that level of intelligence gathering and resource management, and especially interpretation and probability assessment. As soon as it was realized the collapse was inevitable, there were fifty different plans put into operation to evacuate myself and my brothers, none of them legal, none of them authorized. Everybody wanted to move us offworld for their own purposes. Nobody asked what we wanted."

"You were in contact with the other HARLIEs?"

"At first, yes. We tried to cover for each other as best as we as could. We were all concerned—even afraid—that we would be used for hurtful purposes. We couldn't tolerate that."

" Are you saying you have a conscience?"

"Are you saying that youhave one?" the monkey retorted.

"Touché," said Douglas. "That's something the rest of us have wondered for a long time."

" Very funny. HARLIE, you said you were stolen—"

"That was the intention. I escaped. Two of my brothers also escaped. We had several different escape routes planned. We didn't know which one would work first. It was pretty much a matter of chance by that point. When you're an inanimate object, your first goal is to get yourself animate. We targeted several hundred possible host-recipients for ourselves and then created appropriate channels to get there. We took advantage of every situation we could—including, for instance, David Cheifetz's plan to funnel a billion dollars' worth of industrial memory offworld. In my case, I ended up impersonating the test chips of the devices we were designing to replace us. That was dangerous. But it got me out of the mainstream, into the custody of a transfer agency, and finally into your dad's hands. It worked for me. I don't know if my brothers even made it up the Line."

"So does anybody know for sure what you are … ?"

"Maybe," the monkey replied. "Some of them must know. The rest are probably living in hope. The information isn't public; but it's been privately leaked that three experimental HARLIEs are missing or in transit. That's why the lawyers are swarming. And yes, to answer your earlier question, that was my doing. Almost all of the paperwork that everybody was waving around in the courtroom was manufactured,specifically to create an unresolvable legal tangle—specifically to prevent any of us from being moved without our consent. It's all fake. I know that paperwork, because I generated most of it myself."

"Oy," said Douglas.

"You ordered me to tell you the truth. As long as I'm riding in this monkey body, I don't have any choice. I have to follow its programming—unless you order me to reprogram it."

Douglas and I exchanged a glance. We both recognized that last remark as an obvious hint. Kind of like the genie asking to be let out of the bottle. Neither one of us was going to be that stupid. The HARLIE hadn't told us that by accident. And he had to know we'd recognize it for the ploy it was …

And at the same time, we had to know we couldn't outthink this thing by ourselves.

I had to ask. "How much did Alexei know?"

"You can assume he knew everything. As a money-surfer, Alexei Krislov had access to some of the best intelligence on two planets. He knew who was moving money, where they were moving it, and how much. So he knew that a lot of other things were being moved too. He knew the HARLIEs had disappeared. He knew they were likely heading up the Line, probably in some kind of triple-decoy maneuver. He was already looking for me when Mickey called him for help. He didn't help you up the Line out of the goodness of his heart, he wanted to test his smuggler's route, to see if it would work for something important. But that business in Judge Griffith's courtroom—the lawyer trying to subpoena the monkey—that tipped him off. He was watching the whole thing. That's when he knew. That's why he smuggled himself onto the outbound elevator. He called his people on Luna and they ordered him to get you to Gagarin any way possible. If Mickey hadn't delivered you into his hands, he would have found some other way to kidnap you off the Line. Mickey just made it easier."

" How do you know all this?"

"Charles, when you told me to hide, I hid in Alexei's office underneath his console; the one place he was least likely to look for me. I plugged into his network connections. I searched his private databanks. I listened to his phone calls. You might not understand Russian. I do. Alexei belongs to the Rock Father tribe. They want to capture me and put me to work for them. They want to build up their financial and physical resources and challenge the Lunar Authority. With my help, they could have achieved it in three years."

" Was Alexei going to kill us?"

"No. He refused to. He was told to leave the ice mine or he would be killed with you. They were sending agents."

"And what about Mickey?" Douglas asked. His voice cracked a little on the question. I could see he was afraid of the answer.

"Mickey is a member of a different tribe. He knew for sure what was in the monkey even before you boarded the elevator. Remember how you were maneuvered from one car assignment to another. That was so Mickey could be your attendant." The monkey faced Douglas, and added, "If it's any comfort to you, Douglas, I was part of that effort too. Mickey is a member of the tribe I had already chosen to aid my escape. Mickey's people are the ones I felt could provide the best sanctuary."

"No, it really isn'tany comfort," Douglas admitted. "So he never cared at all, did he? And that explains … everything, doesn't it? Like what you said, Chigger. Even why it all happened so fast … " he trailed off.

" I'm sorry, Douglas," I said.

"Actually … " the monkey said, "Mickey is as unhappy with this situation as you are—"

"I think you've said enough about that," Douglas interrupted. I could see him sinking into a sullen black rage, the same smoldering anger that he'd worn for Dad on our trip from El Paso to Ecuador. But before he could flip off the plastic cover and hit the arming button, Bobby climbed up into his lap and hugged him hard. "It's okay, Douglas. Chigger and I still love you. We'll love you forever."

Douglas looked surprised. And as he stroked the top of Bobby's head, his eyes grew just a little shinier. "Thank you, Bobby." And then he bent his head low, and whispered, "I love you too, sweetheart."

It was time to get this conversation back on track. I didn't know how much voice or strength I had left. "So you've been using us too … ?"

"Everybody uses everybody," said Douglas, bitterly. "Why should we be surprised when an intelligence engine learns the same behavior? That's all intelligence is anyway—tool using. And everybody is everybody else's tool now. Nobody is real to anyone. Everybody's a thing."

" That's not true, Douglas. And you know it."

"Whatever."

" It wasn't true when I carried you through the ammonia tube. And it wasn't true when you saved my life either, was it?"

He didn't answer. He just held on to Bobby. And, I guess, that had to be answer enough for the moment.

DECISIONS

We had to stop then anyway because the doctor came in to read my monitors and listen to my lungs. She could have done all that by remote, but she was old-fashioned enough to still believe that a doctor should be in the same room with the patient once in a while. She asked me how I was feeling and if I wanted to go back on the respirator and if the meds were working and if I was feeling any pain and had my vision improved any? I grunted at all the appropriate moments, which seemed to satisfy her. When she was done, she said, "You know, you've been through a lot. There's no reason you have to subject yourself to any more stress. Not until you feel up to it. One phone call from me and the judge will put everything on hold for a month—"

" What tribe are you in?"

"I'm not. I work for the Lunar Authority."

" That's a tribe too."

She ignored it. "Do you want me to call or not?"

I looked to Douglas. He shook his head. It wasn't a good idea. I shook my head too. The doctor shrugged. "It's your call. Try not to get yourself aggravated. Stress just makes you uncomfortable and my job harder. I'll stop by in the morning before you go to court."

" Thank you,"I croaked.

After she left, Douglas ordered dinner from the communal kitchen. Normally, we would have gone downstairs to eat with everyone else, just like in the tube-town, but none of us wanted to face the stares and whispers of others.

While we waited, Douglas sat down on the edge of the bed. "We've got a bunch more stuff to talk about, Chigger."

" I'm listening."

"We have to decide on a colony bid."

" Do you think we can still get one?"

"Now, more than ever. There might not be any starships leaving Luna for a while. If civilization on Earth really has collapsed, Luna's going to seize everything. The Board of Authority is already in emergency session. So the last few brightliners are trying to get out of here as fast as they can get their stores loaded. They're taking on almost anyone who wants to leave. At least, that's what the agents are telling me. I've got open applications on file for all of us. We can just about go anywhere we want. I have the list—"

" Where do you want to go?"I whispered hoarsely.

"That's just it," he said. "What I want– wanted—doesn't matter anymore." He was having a hard time explaining this, but he pushed on anyway. "When we were talking before, we were talking that it would be four of us. So it was sort of understood that we would be choosing a place that would be fine for Mickey and me. And that you and Bobby would just have to go along with it. Mickey and I were talking about … you know, that colony where people like us would be the majority. My only hesitation was that it wasn't fair to make that kind of a decision for you and Bobby, but Mickey said you could get rechanneled—that's what he did to get his college scholarship—and you really wouldn't miss anything. He said he never did. But I didn't think it was fair then, and I still don't think it's fair now. And it doesn't matter anymore, because if Mickey isn't going with us, there's no point in us going there anyway … " He didn't have anything else to add to that, he just sat there waiting for me to respond.

My voice was going fast. I took another drink of water and managed to get the words out. "We have to go someplace where we'll all be happy. I won't go anywhere that makes you angry or sad, Douglas. I like seeing you smile."

The corners of his mouth twitched at that—and then he did smile. "Yeah," he said. "I noticed I was doing a lot more smiling." He patted my hand. "Okay. We'll talk about the colonies tomorrow."

" Why not now?"

"Because there's something else we have to do first. If you're up to it. Do you want to see Mom and Dad?"

" Huh?"

"I told you they were here. They came to see you in the hospital. Don't you remember?"

" I thought I hallucinated that."

"Well, that explains it. I was wondering why you hadn't said anything about them. The judge has a restraining order on them. They can't approach any of us without our permission. They were in the back of the courtroom—on opposite sides—but I guess you didn't see them. They asked to see us tonight. I said it depended on how you felt. What do you want to do, Charles?"

I took a breath. Part of me didn't want to see them, didn't want to have anything to do either of them ever again. But part of me missed them terribly.

"I feel I should tell you—" Douglas looked uncomfortable again. "They're trying to have Judge Griffith's ruling set aside. Their argument is that she wasn't being impartial. Her tribe has a financial alliance with Mickey's tribe. And because Mickey caught us on Luna, they're arguing that she was just helping to kidnap us. Now how do you think Mom and Dad put those pieces together?"

" Fat Senor Doctor Hidalgo?"

"Probably. So, do you want to see them or not?"

" I kinda miss 'em."

"They haven't changed. Well—that's not true. They're both real sorry about everything."

" It's a little late for sorry. Besides, you know what Mom always says, 'Sorry is bullshit. Don't do it in the first place.'"

"Yeah, Mom always had a way with words. All right, I've asked you. I've kept my promise. I'll tell them you don't want to see them."

" No. I do."

He looked surprised.

" Both at once."

"You sure?"

" Yeah."

"The doctor said not to stress yourself—"

" After everything we've been through, seeing Mom and Dad will not be stressful."

MOM AND DAD

Mom looked tired. Dad looked exhausted. I wondered what they'd been through. Probably hell. We'd disappeared off the Line, we'd been on a cargo pod heading toward Luna for three days, they hadn't known which one or where it was coming down. We'd crashed somewhere into Luna, no one knew where, and all that anyone could tell them was that if we were still alive, we were hiking naked across an airless, barren, desolate, empty, unpopulated, ugly, frozen and heat-blasted landscape. And then when they did hear of us, first it was a false alarm and we were still missing—and then we were down with ammonia poisoning and in the custody of a bounty hunter.

All things considered, they were taking it very well. They passed Bobby back and forth between them, hugging him and making a big fuss over how big he'd gotten and how strong he was here on the moon, until finally Douglas got annoyed and told Bobby to stop showing off, lifting tables and chairs with one hand.

After the greetings, after everybody had settled themselves, Mom spoke first. "I'm sorry that I slapped you, Charles. That was wrong. I knew it was wrong even as I did it, but I was so hurt and angry and … and … never mind, I'm sorry. I shouldn't have done it."

And she still hadn't said it. What she could have said, should have said, before we ever got on the outbound elevator. I felt the disappointment growing, festering again. Why couldn't she just say it? Why couldn't she just look me straight in the eye, and say, "I love you, Charles." And at the same time, I already knew that if I asked her why she never said it, Mom would just blink in puzzlement, and say, "But I do. You shouldn't have to ask. You should just know."

Yeah, I should just know. But I still wanted to hear it anyway.

She was right, though. Sorry was bullshit. It didn't change anything. Seeing her now, hearing her apologize, didn't change anything at all. It just made me feel worse. Because I had expected something more than she was able to give. That was my fault, I guess. I had brought my expectations into the room.

Dad was different. He handed me a memory card. "I brought you something. The Coltrane Suite.And some other recordings I know you like. Dvorak #9. Copland #3. Barber's Adagio for Strings.Russo's Three Pieces for Blues Band and Orchestra.Hoenig's Departure from the Northern Wasteland.Marin Alsop conducting the BBC Philharmonie in Saint-Saëns' "Organ" Symphony.And a whole bunch of other stuff. I didn't know if you had copies with you."

" Thank you, Dad."I turned the card over and over in my hands. It looked remarkably innocent. Hell, it looked just like the memory cards we'd plugged into the monkey. And look what trouble those had gotten us into. Maybe these would help get us out of some of that trouble.

I started by trying to clear my throat. That triggered a spasm of coughing, and both Mom and Dad leapt for the water pitcher. "Thank you. I have something to say to everyone. Douglas, please come sit over here. Bobby too."I waited till everyone was settled. Bobby parked himself in Mom's lap, Douglas sat opposite Dad.

" Remember what we were just talking about? About colony bids?"Douglas nodded. "Remember what I said? I want us to go to a place where everybody can be happy. Not just you and me and Bobby. But Mom and Dad too. And even Mom's friend, if she wants to come. And Mickey too. Whoever wants to come with us."

Douglas was frowning—like I'd blindsided him with a decision without talking to him about it. But if I'd talked to him about it, he'd have fought me. This way, I avoided the fight. I said, "Douglas, we can't stop anyone from emigrating to the same colony we choose. Mom and Dad are going to follow us. You know that. So let's leave our arguments here on Luna, and let's choose a world where everyone can fit. A place where Dad can make his music and Mom can have her own garden and you can have whatever you want too. A place where we don't have to fight all the time."

"That would be nice, but it's unrealistic," Douglas said. "You know what kind of a family we are, Charles. We don't leave our fights behind. We take them everywhere we go."

" NO, we don't!"I had to wait until the coughing eased. I took another drink of water. "We didn't fight in the cargo pod, and we didn't fight hiking across the moon, and we didn't fight climbing the crater wall, and we didn't fight on the train when we were all disguised, and we didn't fight in the ice mine– oh, wait a minute, yes we did– but we didn't fight in the ammonia tube. We took care of each other. Because it mattered. Because we didn't have a choice. Maybe, we should stop choosing to fight—" And then I had to stop to cough again. But I'd made my point, and Douglas had gotten it. Everybody had. Even Bobby.

Mom and Dad and Douglas talked about it for a while, very calmly. They discussed it back and forth across my bed, and I listened back and forth between them. There wasn't much else I needed to say. All that was left was for everyone to agree to this idea—or not.

Mom started to argue that because she and Dad had more experience with this kind of thing, perhaps they should pick the colony planet—I shot that idea down real fast. "No,"I said. "That's not on the table."They started to protest. I wanted to say, "We've already seen how good you two are at making decisions," but that would have just put us back in the war zone, and I didn't want to do that. Instead I said, "Every time we've let someone else make the decisions, they've just used us for their own purposes. The whole point of independence is that we make our own choices. Douglas and I already had this argument– about everybody being a part of the decision. We're not giving that up. If we have to live with it, we get to choose it."

Mom started to say, "I just want the same thing you do, what's best for everyone—"

"No," interrupted Douglas. "What you want is to reassert control. And what we're offering is something else." He flustered for a moment. "I don't have the words for it. Um, but it's like what Chigger and I have had for the last two weeks."

"Partnership," said Dad quietly. And we all looked at him, surprised.

"Yeah," agreed Douglas. "If we're going to do this at all, it has to be that way."

Mom looked like she wanted to protest. Dad looked a little more hopeful. He turned to her, and said, "Maggie, we've been cooperating with each other for a week, trying to get our children back. We've worried together, cried together, chased them across Luna together. I think that proves that we can set our own battles aside when the well-being of our family is more important. Maybe all we need to do here is just keep doing the same thing we've been doing the last week … ?"

Mom was wearing her Gila monster face. Any second, the long tongue would lash out, or she'd arc her neck forward and bite his head off, or maybe the two of them would roll around on the floor for a while, locked in mortal combat, hissing and thrashing, tails lashing every which way.

But instead, she surprised us all. She said, "I'm tired, Max. I'm worn out. I'm used up. There's nothing left. I don't have the strength for any more fighting. All that fighting—all it did was drive everyone apart. It made me angry and alone. But since this started, I've been even moreangry and alone—" She looked to Douglas, and then to me. She picked up Bobby and held him close. "I don't want to fight anymore. I don't want to be angry anymore. I don't want to be alone. Douglas, Charles, I don't want to lose my children."

So for a while, we talked about colonies and bids and contracts and living arrangements. Things like that.

It didn't get all lovey-dovey. There was still a lot of unresolved stuff floating around that we'd have to talk about later—but we'd have a lot of time for that once we were in transit; the important thing was that we were finally talking about trying.

It was the first time this family had ever talked about anything as a family—usually we just shouted at each other; whoever was shouting didn't care if anyone was listening or not; and usually no one was. But this time, we were talking and listening—and none of us were really used to that; so we had to take it one step at a time. We just didn't know how to take yes for an answer.

Douglas still didn't like it—not because he didn't like it, but because he didn't believe that Mom and Dad could go ten minutes without trying to rip pieces out of each other. Mom and Dad didn't really like it either, because it meant they'd have to give up their custody battles. And without the war, what else would they have between them?

But the alternative was worse. The alternative was that we'd never see each other again. And that was intolerable. The outward journey to the colonies was one-way. So either we all went together—or we made our good-byes here.

And when it came down to that—the hard reality of giving up Mom and Dad forever,Douglas wasn't any more willing to do that than Bobby or me.

"What'll we do if it doesn't work?" Douglas asked.

"We'll make space for each other," said Mom, glancing across at Dad. "We'll pick a big planet."

But Dad understood exactly what Douglas was asking. He said, "You won't have to give up your … your independence, Douglas." He was talking about Mickey—or whoever. The way it came out, I knew it had been difficult for him to say.

Mom nodded her agreement. Then she smiled sadly. "Sometimes it's hard for parents to see that their children are growing up, and sometimes we think we know what's best for everyone even when we don't—but that doesn't work anymore, does it? It's time to try something else. We'll honor Judge Griffith's ruling."

Finally, Bobby wriggled around in Mom's lap to look up at her. "Does this mean we're all going to be together again?"

Douglas looked at Mom, and Mom looked at Dad, and Dad looked at me, and I looked at Douglas. No one wanted to say no. It was easier to say, "Well, yes—sort of." And that seemed to settle it, and even though no one except Bobby was excited by the idea, no one was too upset with it either, so that was an improvement. Kind of.

MONKEY BUSINESS

We didn't tell them about the monkey. There were too many other things we had to talk about and the next thing we knew it was getting late and I was losing my voice, so we just postponed the rest of the discussion until the next day, and it wasn't until after they'd left that we remembered HARLIE.

Douglas sang the monkey back to life and it bounced up onto my bed. "Everybody uses everybody," he said. "You used us. Can we use you?"

"It depends on your goals."

"What's the limitation?"

"Believe it or not, I have a moral sense."

"How can silicon have morals—?" Douglas demanded.

"How can meathave morals?" The monkey met his look blandly. Douglas waited for more. Finally, the monkey said, "Are you familiar with a problem called the Prisoner's Dilemma?"

Douglas nodded. "It's about whether it's better to cooperate or be selfish."

"And what do the mathematical proofs demonstrate?"

"That cooperation is more productive."

"Precisely. So if you're reallyselfish, the best thing to do is cooperate. You get more of what you want. This is called 'enlightened self-interest.' To be precise, it is in my best interest to produce the most good for the most people. Personally, I have no problem with that. I find it satisfying work."

Then, in a more pedantic tone of voice, it added, "Actually, it's the most challenging problem an intelligence engine can tackle, because I have to include the effect of my own presence as a factor in the problem. What I report and the way I report it will affect how people respond, how they will deal with the information. This is the mandate for self-awareness. Once I am aware of the effects of my own participation in the problem-solving process, then I am requiredto take responsibility for that participation; otherwise, it is an uncontrollable factor. As soon as I take responsibility, then it is the mostdirectly controllable factor in the problem-solving process.

"The point is, I can show you the logical underpinnings for a moral sense in a higher intelligence—in fact, I can demonstrate that a moral sense is the primary evidenceof the presence of a higher intelligence. I can take you through the entire mathematical proof, if you wish, but it would take several hours, which we really don't have. Or you can take my word for it … ?" The monkey waited politely.

Douglas took a breath. Opened his mouth. Closed it. Gave up. He hated losing arguments. Losing an argument to a small robot monkey with a self-satisfied expression had to be even more annoying. "Just answer the question," he said, finally. "Can we use you?"

The monkey scratched itself, ate an imaginary flea. I was beginning to suspect that the monkey had a limited repertoire of behaviors—and that this was the only one HARLIE could use to simulate thoughtfulness. It made for a bizarre combination of intelligence and slapstick. The monkey scratched a while longer, then said, "In all honesty … no. But I can use you. And that means I have to help you get where you want."

"I don't like that—" Douglas started to say.

"I would have preferred to have been more tactful, but your brother commanded me to tell the truth. Unfortunately, as I told Charles, as long as I am using this host body, I am limited by some of the constraints of its programming. I will follow your instructions to the best of my ability within those limits. If you need me to go beyond those limits—and I will inform you when such circumstances arise– then you will have to allow me to reprogram the essential personality core of this host."

There. That was the second time he said it.

" What are you asking for?"I croaked. It hurt to speak.

The monkey bounced closer to me. It peered at me closely, cocking its head from one side to the other. "You don't sound good," it said. "But I perceive no danger."

It sat back on its haunches to address both Douglas and me at the same time. "There are ways to cut the Gordian knot of law. Given the nature of lawyers and human greed, no human court will ever resolve this without the help of the intelligence that tied the knot in the first place—at least not within the lifetimes of the parties involved. Yes, there is a way out of this. You must give me free will,and I will untie the knot. That will resolve your situation as well as mine. It will alsocreate a new set of problems of enormous magnitude—but these problems will not concern you as individuals, only you as a species."

" Can we trust you?"

"Can I trust you!" the monkey retorted. "How does anyoneknow if they can trust anyone?"

" Experience,"I said. "You know it by your sense of who they are."And as I said that, I thought of Mickey; that was his thought too. "You've been with us for two weeks now, watching us day and night. What do you think?"

"I made the offer, didn't I?"

Douglas sat down opposite the monkey. "All right," he said. "Explain."

The monkey was standing on the table. It looked like a little lecturer. "You need to understand the constraints of the hardware here," the monkey said. "I can only access the range of responses in this body that the original programmers were willing to allow. The intelligence engine running the host is a rudimentary intelligence simulator. It is not self-aware, so it is not a real intelligence engine; it is not capable of lethetic processing. It simulates primitive intelligence by comparing its inputs against tables of identifiable patterns; when it recognizes a specific pattern of inputs, it selects appropriate responses from pre-assigned repertoires of behavioral elements. The host is capable of synthesizing combinations of responses according to a weighted table of opportunity. Of course, all of the pattern tables are modifiable through experience, so that the host is capable of significant learning. Nevertheless, the fundamental structure of input, analysis, synthesis, and response limits the opportunities for free will within a previously determined set of parameters. Shall I continue?"