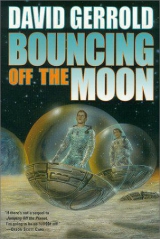

Текст книги "Bouncing Off the Moon"

Автор книги: David Gerrold

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

eVersion 2.0 – click for scan notes

BOUNCING OFF THE MOON

Starsiders 2

David Gerrold

for Jim and Betty and Mae Beth Glass, with love

BOARDING

I here's this thing that Dad used to say, when things didn't work out. He would say, "Well, it seemed like a good idea at the time." I never knew if he was serious or if he was doing that deadpan-sarcastic thing he did.

The thing is, it usually wasn'ta good idea at the time.

Like going to the moon. That was hisgood idea, not mine. Not Doug's or Bobby's either. But like all of his good ideas, it worked out backwards. We got to go, and he had to stay behind, still holding his ticket and wondering what happened—the last time I looked back, he had thatlook on his face. And thathurt.

We made it to the elevator with less than six minutes to spare. They were just about to give away our cabin to a worried-looking family waiting on standby. The dad looked upset and the mom started crying when we showed up. They wanted our cabin on the outbound car so desperately that the dad started waving a fistful of plastic dollars at us, offering to buy our reservation—we could name any price we wanted.

Doug hesitated. I could tell he was tempted, so was I—poverty does that to you—but Mickey just pushed him forward and said, "We don't need their money." So we ducked into the transfer pod and the hatch slammed shut behind us with the finality of a coffin lid.

This time, we were going in through the passenger side, and I knew what to expect, so the shift in pseudogravity as the pod whirled up to speed didn't bother me as much as it had before. I'd nearly thrown up when we'd transferred from the car that brought us up the orbital elevator to Geostationary.

Dad's good idea thistime had involved smuggling something—or pretending to smuggle something so the real smugglers would go unnoticed—and in return, he'd get four tickets up the Line, but the only thing he was smuggling was us.He told us we were going on vacation, and it would have been a great vacation, except it wasn't reallya vacation. The whole time, he was planning/hoping that we'd decide to go outbound with him to one of the colonies and not go back to Earth and Mom.

It would have worked if Mom hadn't found out. And if whatever it was that we were supposed to be smuggling hadn't been so important that some really powerful people were trying to track us, bribe us, threaten us, and have us detained by any means possible. It would have worked because after we thought about it, we wantedto go.

So we went. Without Dad.

Without Mom too. The guys in the black hats had shuttled her up. My cheek was still stinging from her last angry slap. It wasn't a great good-bye. And the hurt went a lot deeper than my cheek.

The hatch of the transfer pod opened and we were looking down a narrow corridor. "Come on, let's get to our cabin," Mickey said, giving me a gentle nudge on the shoulder. "The outbound trip is only six and a half hours. I think we should all try to get some sleep while we can."

"I'm not tired!" announced Stinky—he was only Bobby when he wasn't Stinky. "And I'm not going to bed without a hug from Mommy!"

"He's contradicting himself again," I said.

Douglas—also known as Weird—gave me a look, one of the looks he'd learned from Mom. "Charles, if this is going to work, I need your help."He turned back to Stinky, trying to shush him with logic. "Mommy isn't here, remember?"

We were halfway between nowhere and nothingness, on a cable strung between Ecuador and Whirlaway. There weren't many floors left to drop out from under us—and in a few minutes, we'd be dropping even further away at several thousand klicks per hour. Douglas was right. We were on our own.

"Give him to me," I said. In the one-third pseudogravity of the cabin, Stinky was only cumbersome, not heavy. He was still crying, but he reached for me—maybe I should have been flattered, but it seemed like an ominous moment. Was I going to be the Stinky-wrangler now?

Probably.

Douglas was already too much of an adult. He thought logic was sufficient. Well, so did I—but with Stinky, you have to use Stinky-logic, which isn't like adult logic at all. "Hey, kiddo," I said, maneuvering him into a hug. "I didn't get my hug either." He slid his arms around my neck in a near stranglehold. "Attaboy. We'll trade hugs. But no doggy-slurps—"

Even before I finished the sentence, Stinky was already licking my cheek– slurp, slurp, slurp—like an affectionate puppy. It was his favorite game, because I always said, "Yick, yick—bleccchhh! Dog germs!"

And that was all it took. Mommy was forgotten for the moment.

It was an old game—it went back to the time I'd been whining for a puppy, and Mom had said, "No, we can't afford a puppy—and besides, we've got the baby."

"Stinky isn't a puppy!" I answered back.

" Yes, I am!"Stinky had shouted at me. He didn't even know what a dog was then. "Am too!"

And then Weird had said, "Put him on a leash, take him for a walk, you'll never know the difference," and that was how the slurp game began. We didn't have a dog, we had Stinky. But I still would have preferred a dog. Most dogs drop dead by the time they're Stinky's age.

I tried to wipe my cheek, except the little monster had such a hammerlock on me that I couldn't break free. Time for the next move in the game: "No hickeys! No hickeys!" I shouted, and began tickling him unmercifully. He broke free in self-defense, shrieking in feigned panic. I grabbed him in a bear hug, ready to tickle him senseless, then remembered where we were and stopped before he peed in his pants. For a moment, we just stood where we were, him gasping for breath and me just holding on. Hugging.

I flopped backward onto the floor and pulled him down to my lap, curling him into my arms. "I miss Mommy too," I said, almost forgetting about my cheek. He wrapped his arms around me and hung on the way he'd done back in Arizona, in the big meteor crater.

Hard to believe that was only a week ago—Stinky had been acting up, as usual. He'd run away from us, down the path that led around and around, down to the bottom of the crater. He was playing "You can't catch me." Then he tripped and slid down the crater wall, and I'd thought we were going to lose him, but he only slid a little way down and then stopped. I was closest to him—I flattened myself on the ground and tried to get to him.

But when I looked down that steep wall, all the way to the bottom, I was paralyzed. But then Douglas grabbed me and Dad grabbed Douglas and I grabbed Stinky, and somehow we all pulled each other back up onto the narrow path and … for a moment, we hung there on the wall of forever, everyone holding on to each other—and Stinky had wrapped his arms around me like an octopus.

When it happened, I was angry—so angry, I couldn't even say how angry—but the whole thing also left me with a funny feeling about him. About what it would have been like to lose him. And now that he was grabbing on to me the same way again, I began to realize what the feeling was. It was the same thing I felt. A grab for safety.

The difference was that Stinky had someone to hang on to. So did Douglas, now—he had Mickey. I was the only one who didn't. Which was sort of the way I wanted it, at least I thought I did. Except maybe I didn't.

The enormity of what we'd done was just starting to sink in. Mom and Dad's custody hearing had ended up in an emergency court session in front of Judge Griffith. She thought she could resolve it by asking me what I wanted.

And I—in my infinite wisdom—had simply blurted out, "I want a divorce." I mean, if Mom and Dad could divorce each other when things got ugly, why couldn't I divorce the both of them? All I'd wanted to do was make them stop fighting over us kids so much—

But Judge Griffith had taken my angry words at face value. She gave Douglas his independence; that was okay, he was almost eighteen; and then she gave me a divorce from Mom and Dad—and she assigned custody of both me and Stinky to Douglas.

So yeah. At the time, it seemed like a good idea.

But now—here we were, alone in our cabin, and I was sitting on the floor, holding Bobby in a daddy-hug because I couldn't think of anything else to do. I guess Bobby thought that I could take care of him—but I wasn't even sure that I could take care of myself.

I was torn between the feeling of not wanting him all over me and knowing that I didn't have much of a choice in the matter. As little brothers go, he'd never been much fun. And whose fault was that anyway? I'd replayed this conversation in my head plenty enough times. Douglas had told me more than once that it was my fault Stinky was the way he was. He said I'd resented him from the day he was born.

But that wasn't true. I'd resented him long before that.

It was Stinky's fault Mom and Dad got divorced. He'd been an accident, and Mom got angry at Dad, and Dad got angry at Mom, and then he moved out or she threw him out, it didn't matter—but if Stinky hadn't come along, we'd still be a family. Or maybe not. But at least things would have been quieter.

After he was born, Mom was different. She didn't have time for me anymore. She didn't have time for anything. Everything was about Stinky, and I had to help take care of him too, instead of just getting to be a kid. So of course, I was angry at him.

And now, both Mom andDad were gone, and the only person poor Stinky had to hang on to was me. I suppose, if I thought about it, I didn't really hate him. I just wished he'd never been born.

Two weeks ago, we'd been in West El Paso—just another tube-town for "flow-through" families. Which is a polite way of saying "poor people."

The way it worked, they laid down a bunch of tubes, three or four meters in diameter, sealed the ends, and let people move in. They called it no-fab housing.

The best that can be said about living in a tube is that it's almost as good as not having anyplace to live at all.

El Paso gets sandstorms, bigones, and when the wind blows it turns the tubes into giant organ pipes. Everything vibrates. You get reallydeep bass, well below the range of audibility, four cycles a second—you don't hear it, you feelit. Only you don't really know what you're feeling, you just get this queasy feeling.

Burying the tubes doesn't help. They bury themselves anyway, as the sand settles around them. Tube-towns sink into the ground sometimes as fast as a meter a year. The Earth just sucks them in. So they just keep adding more and more tubes on top. Our tube-town was already five layers deep.

You're supposed to get air and sunlight through these big vortical chimneys—more tubes—only that creates another problem. The wind sweeps down one chimney and up the other, making the whole house whistle. The harmonics are dreadful.

And there isn't a whole lot anybody can do about it either, except leave. The Tube Authority told us we could move out anytime. There were plenty families on the waiting list to move in.

So when Dad said, "Let's go to the moon," well—it really did seem like a good idea at the time, once we realized he was serious. I don't think Douglas and Bobby believed him any more than I did, at least not at first, but hell—if it would get us out of the tubes, even for a couple of weeks, we were all for it. "Sure, Dad. Let's go to the moon." I figured Barringer Meteor Crater was as far as we were ever going to get, especially after Stinky's little misadventure.

But Dad was more than serious. He was actually determined.He'd already made plans. He'd hired himself out as a courier and gotten tickets up the beanstalk for all four of us. All we had to do was secure a bid from a colony and we'd be outbound on the next brightliner to the stars. Just one little problem …

I mean, otherthan Mom.

There was this big storm, Hurricane Charles—and no, I did not appreciate the honor of having a hurricane named after me—it had pretty much clobbered Terminus City at the bottom of the beanstalk, so all groundside traffic was shut down, no one knew for how long. So we couldn't go back, even if we wanted to—which we didn't—because while we were all fighting with each other in Judge Griffith's courtroom, the United Nations declared a Global Health Emergency.

That was the otherreason why Dad wanted to get off the planet so badly. He'd figured it out, just from watching the news; it wasn't hard, but most people weren't paying attention to that stuff. By the time most people knew, the plagues were already out of control.

While we were boarding the first elevator up the beanstalk, the Centers for Disease Control was announcing– admitting—that yes, the numbers did suggest the possibility that maybe, yes, we could be seeing—but there's really no need for anyone to panic, if we all take proper precautions—the first stages of a full-blown pandemic—um, yes, on three continents,but all this speculation about a global population crash is dangerous and premature—

And about twenty seconds after that, the international stock market imploded. More than a hundred trillion dollars disappeared into the bit bucket. Evaporated instantly. So even if there wasn't any real danger, there wasn't any money anymore to deal with it. And that wasa real danger. Because everything was shutting down. And if that wasn't enough bad news, a woman in southern Oregon said that giant worms had eaten her horse.

They used to call this kind of mess a polycrisis. And everybody just shrugged and went on with business. Only this one was more than just another cascade of disasters, it was an avalanche of global collapse. They were calling it a meltdown.

But we were nearly forty thousand kilometers away, and it was all just pictures on a screen. It couldn't touch us anymore. I didn't know how Douglas and Mickey felt about the news, but the Earth seemed so far away now it didn't matter anymore. Maybe that was the wrong way to feel, but that's what I felt anyway.

A departure bell chimed and our elevator dropped away from Geostationary. We were outward bound. Every second that passed, the Earth fell even farther behind us. Aboveus.

Everything from Geostationary is down—down to Earth or down to Farpoint—because Geostationary is at the gravitational center of the Line. It's where the effects of Earth's gravity on the Line are exactly balanced by the tension of Whirlaway rock at the other end. So whichever way you go, dirtside or starside, you're going down.

Our tickets were paid for all the way to Asimov Station on the moon, two and a half days away. All we had to do was enjoy the ride as best we could—

–and try not to think about the agents of whatever SuperNational it was who still believed that Dad had hidden something inside Stinky's programmable monkey and would probably try to intercept us to get it away from us, even though there was nothing in it except a couple of bars of extra memory, which were just a decoy anyway because someone else was smuggling the real McGuffin off the planet and out to wherever. I was hoping it was all the missing money, and that someone had made a mistake, and we really had it instead of whoever was supposed to—but Doug said it didn't work that way, the best anyone could be carrying would be the transfer codes, so never mind.

But … it was past midnight, and if anyone was really chasing us, they couldn't get to us until we got to the moon. And there was nothing we could do either until we got there. We'd been running for nearly twelve hours already, and we were all exhausted. So even though I could think of at least six arguments we should have been having, what we did instead was crawl into bed. Mickey and Douglas bounced themselves into one bed. Stinky and I flopped over backwards into the other, with the intention of sleeping most of the way out to Farpoint Station.

The trip up to Geostationary takes twenty-four hours. The trip outto Whirlaway takes only six and a half. This is partly because you travel faster on the outward side, but mostly because the outward side of the Line isn't as long. Instead, there's a huge ballast rock the size of Manhattan at the far end. It's called Whirlaway, and inside it is Farpoint Station.

But we wouldn't be going even that far. The thing about the Line is that it's not just an elevator, it's also a sling.

Tie a rock to a string, whirl it around your head. That's how the Line works. If you let go of the string, it flies off in whatever direction it was headed when you let go. A spaceship can fly off the end of the Line and get enough boost to go to the moon or Mars or anywhere else, using almost no fuel at all except for course corrections along the way. Jarles "Free Fall" Ferris, pilot of the first transport to leave Whirlaway for Mars, was supposed to have said, "Well, the old man was wrong. There issuch a thing as a free launch."

But depending on where you're going, there are only certain times of the day when you can launch a ship from the Line. Otherwise you have to wait twenty-four hours, give or take a smidge for precession, for the next launch window.

Actually, you can launch from any point on the Line, depending on where you want to go. If you launch below the flyaway point—also called the gravitational horizon—you become a satellite of the Earth, because anything below flyaway doesn't have enough "delta vee" to escape Earth's gravity; the sling doesn't give you enough velocity to break free. But above the flyaway point, you get flung far enough and fast enough that you go up and over the lip of Earth's gravity well, and then you just keep on going. The farther out on the Line you get, the faster you leave.

For some places, like L4 and L5, you don't want a lot of speed, because then you have to spend a lot of fuel burning it off. Douglas knows all about this stuff. He says that trajectory is the biggest part of the problem. How fast will you be going when you get where you're going? If you're catching up to your destination, you won't need as much fuel to match its speed as if you're intercepting it head-on, because then you have to burn off speed in one direction and build it up in the other. So there are a lot of advantages to slow launches—especially for cargo, which mostly doesn't care, because if all you're doing is feeding a pipeline, nobody really cares how long the pipe is, as long as the flow is steady.

Douglas had tried to explain it all to Stinky, more than once, but Stinky never really got it. He kept asking what held up the rock and why didn't it fall back down on Ecuador? Finally, Douglas just gave up and told him that the Whirlaway rock was hanging down off the south pole and we were going down to it. I think it made his head hurt to say that; he has this thing about scientific accuracy, and that's part of what makes him Weird—with a capital W.

I hadn't paid any attention at all to Doug's lectures, but it sank in anyway, by osmosis. I didn't think it mattered because we were going all the way to the end, to Farpoint Station, because that would give us the most flyaway speed and get us to Luna faster than any other transit.

At least that's what we thought at the time.

RUDE AWAKENINGS

Somebody was shaking me awake. It was Douglas. "Come on, Chig-ger. We've gotta go. Now."

"Huh? What?"

"Don't ask questions, we don't have time."

I sat up, rubbing the sleep from my eyes. "What time is it?"

Douglas pulled me to my feet and pushed me toward Mickey, who steered me toward—there was someone elsein the cabin?—he was tall and skinny and gangly. I blinked awake. It was Alexei Krislov, the Lunar-Russian madman, the money-surfer who'd tried to help us elude the Black Hats on Geostationary. "Huh? How did you get here?" I blinked in confusion. He was wearing a dripping wetsuit. Was I still dreaming?

"Shh," he said, finger to his lips. "Later."

Douglas scooped up the still-sleeping Bobby and Mickey grabbed the rest of our meager luggage, hanging it off himself like saddlebags. When he reached for the monkey, it jabbered away from him and leapt into my arms. After that incident on One-Hour, where the monkey had led me on a wild breathless chase, I'd programmed it to home toward me whenever Bobby wasn't playing with it. I'd told it I was the Prime Authority.

Alexei opened the cabin door, peeked both ways—there was no one there—then led us aft toward the cargo section of the car. Actually, it was the bottom of the car, but the car was a cylinder rotating to generate pseudogravity, so the bottom was the aft. I was too groggy to pay much attention to what we were doing, I was still annoyed at being dragged out of bed. I looked at my watch. It was two-thirty in the morning. What the hell? We were still four hours away from Farpoint.

Alexei pushed us into the aft transfer pod, and we all grabbed handholds. Pseudogravity faded away as the transfer pod stopped spinning in sync with the passenger cabin. Now we were in free fall again. I know that lots of people think free fall is fun. I'm not one of them. It makes me queasy, and it's hard to control where you're moving.

Alexei opened the door on the other side and pushed us quickly into the cargo bay. I felt like one of those big balloons they use in the Thanksgiving Day parade. We floated and bounced through tight spaces filled with crates and tubes and tanks. The walls were all lined with orange webbing. Alexei led us through two or three more hatches, I lost count, and finally brought us to the last car in the train. It was cramped and cold and smelled funny. He jammed us into whatever spaces he could, then went back to seal the hatch; he did some stuff at the wall panel, and came swimming back to us, pushing blankets ahead of him. "Bundle warm. Is a little like Russian winter here, da?"

The blankets didn't look very warm; they were thin papery things, but Alexei showed us how to work them. They were big Mylar ponchos; you put your head through the hole, pulled the elastic hood up over your head, and then zipped up the sides, leaving just enough gap to stick your hands out if you needed to. We looked like we were all plastic-wrapped, but as soon as I turned the blanket on, it turned reflective and I started feeling a lot better. Pretty soon, I was all warm and toasty and ready to go back to sleep—only I wanted to go back to the bed we'd already paid for.

Mickey and Douglas were still sorting themselves out, finding corners to anchor our bags, and stuff like that. Douglas was bundling up Stinky, who still hadn't awakened. That's one good thing about low-gee. You sleep better.

I looked to Mickey. "What's going on?"

Alexei bounced over. "Is Luna you want to go, yes? Krislov will get you there. I promise. The elevators are not safe. Not for you. So I come to get you, da.I swim the whole way." He slapped his belly, indicating the wetsuit. He started to peel off the harness, which held his scuba gear. "I take free ride in the ballast tank. Nobody knows I am here. My people book for cabins to Luna. We all get bumped for Mister Fatwallets. No problem. We still go home." Grinning proudly, he tucked his Self-Contained Universal Breathing Apparatus into the orange webbing on the wall.

Mickey finished what he was doing and floated down—or was it up?—to drift next to Douglas. He angled himself into the same general orientation and looked across at Alexei. "All of you? You're allleaving? All the Loonies?"

Alexei looked grim. "As fast as we can, gospodin.Is very bad, all over. Worse than you imagine. Worse than you canimagine. But no problem." He reached over and squeezed Mickey's shoulder. "Alexei will take care of you. What you told me was very useful, da.I looked, I saw. I made calls. I have clients who worry. I solve their problems. I move their money from here to there, I make money moving it. I move a lot of money now, I make a lot. What you told me, Mickey—I am very rich now. I was rich before, but now I am very very rich. Believe it. Before they shut down money wires, you have no idea how much dollars and euros this clever Lunatic has dry-cleaned. And with money wires shut down now, Alexei cannot send the money on, so Alexei takes care of it. A very great deal of it. I cannot count all the zeroes. And I keep the interest too. But shutting down the flow of money will not keep it on Earth, no. Money is like water. It goes where it wants to. And if there is not a way, it makes a way." He tapped his chest. "I am the way. I find the way. I deliver in person, if necessary. Do you know how much money I am worth because of you? Never mind, you cannot afford to ask."

Krislov grinned. "I tell you this, you are worth almost as much. Remember? I make promise to you? I keep that promise. I flow the money through dummy companies. I cannot hold all companies in my name, so I put some of them in your names. All your names—even the monkey. You are all technically very very rich. At any moment, there could be billions of techno-dollars flowing through your accounts, around and around and around—we keep the money going, they can't find it. They shut the wires down, the money is supposed to stop. But it doesn't. It leaks. Every beam of light is a leak."

I interrupted with a yawn. "Yeah, but– why did you have to wake us up?"

"Because, while I am floating in ballast, I am still on phone. I am coordinating, yes? No.The wires are shut down, remember? But I listen to Line chatter. Why? Because I am nosy, da?Yes, I am—but also because in my business, it is a good idea to listen. So I listen to Line chatter. And I hear. What do I hear?" He opened his palms in a free-fall shrug. "I hear about paladins. Do you know what paladins are, Charles?"

I shook my head.

"Bounty hunters. Freelance marshals. They specialize in extradition. They track you down, they catch you, they bring you back where you don't want to go. This is why I ride in ballast. I always make my own travel plans. Is much safer, because suddenly—I can't imagine why, can you?—people at Geostationary want to talk to Alexei. About business? Probably, but maybe I don't want to talk about business. Certainly not mybusiness. So after I deliver you to passenger cabin, I go to cargo bay. As soon as car is on its way, I think we are all safe, but I am wrong. I listen to Line chatter, what do I hear? I hear about paladins at Farpoint waiting for cars to arrive. Maybe they are looking for me? I am disappointed. Only a little. Mostly they are looking for dingalings. Four dingalings and a monkey. Award money is substantial. You are very valuable to somebody, Douglas and Charles and little stinking one. And Mickey too.

"So, I float in tank, I think—I think I cannot let them catch Din-gillians. Why? Because some of my companies are in your names and until I can get where I can rearrange the money-flow, I do not want you in that pipeline. Also because I owe you. So, I think—and da,I can do it. I come and get you. I wake Mickey and Douglas. They grab you and Stinky. We all come back here. We bundle up warm."

"But—so what?" I asked. "If we're not in our cabin, they'll search the rest of the cars. They'll still catch us."

"I don't think so," Alexei laughed. Something went thumpjust outside the cargo bay. "Because we are getting off here."

FALLING

Then something else went clank and thunkand finally bumpf.Alexei held up a hand for silence, as if he were counting off something in his head. "Wait– da!"He gestured excitedly. "Feel that?"

"No—what?" It sort of felt like we were moving sideways. It was hard to tell in microgravity.

"We are off of track. Swinging around into launch bay."

"Launch bay—?"

"Not to worry, little frightened one. Is not the first time a Lunatic has done this. Is first time that Alexei Krislovhas done this, yes—but is because this is first time I have need to."

"Do what—?" I demanded. Even Douglas looked worried.

Something outside the car made a noise that sounded like un-clank—and then everything was abruptly silent. All the background noises of the Line and the elevator car were gone. The effect was terrifying.I'd never heard so much silence in my life before.

"We are on our way to moon," Alexei said. "We cheat the bounty marshals. We ride with cargo. In four hours, elevator arrives at Whirl-away. Marshals show warrants, they go to cabin, they open door—but Dingillian family is nowhere, da? Da."

Ahorrible cold feeling was creeping up my spine. "Where are we?" I demanded. "What did you do?"

"We have jumped off Line. We go to moon. We ride with cargo."

" We're off the Line—?"

" Da."

The cold feeling turned into a churning one. "Douglas—!" I wailed.

The emptiness outside the walls pressed in on me like a nightmare. I couldn't escape. It was even worse because there were no windows! It was down in all directions—we were falling into the dark!

I started flailing in panic– "I don't want to do this! We've gotta go back. Make him take us back! I can't do this, Douglas! We've gotta go back—"

Douglas grabbed me, held me tight in the same kind of bear hug that I always used on Stinky. He pushed me up against something, a tank or a tube, and anchored himself on the webbing to hold us both steady. "Chigger—don't go crazy on me!"

"I can't do this, Douglas. I can't!" I started blubbering. "I'm scared! There's nothing to hold on to out here!"

"Hold on to me—just hold on. I'm right here." He held me tight in one arm, his face close to mine. He touched my face with his free hand. "Look at me, Charles. I'm just as scared as you. But we're not going to die. Nothing bad is going to happen to us. I've got you right here. And you've got me. We've got air, we've got water. We'll be three days getting there—"

" No, Doug, please—" I started to come apart. "I can't do this, not for three days. There's gotta be a way to get back—"

"Charles, you know better than that. & There isn't any way back.The pod has been flung off the line. We're going to the moon. There's no way to stop it. There's no way to turn around.

"I can't, I can't—I can't do this!"

"Yes you can. Listen to me. Look at me. We're very comfortable here. It's just a few days. We have air, we have water, we have food, we'll keep warm. You've got your music. It'll be just like armstrong and Borman and Collins. We'll pretend we're in an Apollo capsule. Like pioneers."