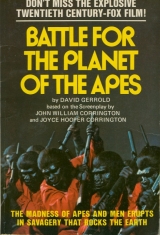

Текст книги "Battle for the Planet of the Apes "

Автор книги: David Gerrold

Жанры:

Альтернативная история

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 8 страниц)

THE CITY OF

THE APES

It was a quiet, peaceful city.

It was a city ruled by apes and served by men.

It was a city unaware of an angry band of vicious gorillas anxious to revolt and an insane cadre of mutated humans hungry to kill.

It was a city on the brink of an horrendous destruction that had happened once—and was suddenly, inexorably, happening again . . .

20th Century-Fox Presents

An Arthur P. Jacobs Production

BATTLE FOR THE PLANET

OF THE APES

Starring

RODDY McDOWALL • CLAUDE AKINS

NATALIE TRUNDY • SEVERN DARDEN

LEW AYRES • PAUL WILLIAMS

and

JOHN HOUSTON

as The Lawgiver

Directed by

J. LEE THOMPSON

Produced by

ARTHUR P. JACOBS

Associate Producer

FRANK CAPRA, JR.

Screenplay by

JOHN WILLIAM CORRINGTON

and JOYCE HOOPER CORRINGTON

Story by

PAUL DEHN

Based on Characters from

PLANET OF THE APES

Music by

LEONARD ROSENMAN

BATTLE FOR THE PLANET OF THE APES

FIRST AWARD PRINTING June 1973

Copyright © 1973 by

Twentieth Century-Fox Film Corporation.

All rights reserved

AWARD BOOKS are published by

Universal-Award House, Inc., a subsidiary of

Universal Publishing and Distributing Corporation,

235 East Forty-fifth Street, New York, N.Y. 10017

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

CONTENTS

Title

Copyright

Dedication

BATTLE FOR THE PLANET

OF THE APES

Prologue

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Epilogue

For Harlan Ellison,

who will appreciate the thought.

PROLOGUE

Many years, many centuries, after the fact, an orangutan sat on a hillside and taught a class. He read to his students from a large handwritten book. And in this manner does history become legend and legend become myth.

“In the beginning, God created Beast and Man, so that both might live in friendship and share dominion over a world at peace.

“But in the fullness of time evil men betrayed God’s trust and, in disobedience to His holy word, waged bloody wars not only against their own kind but also against the apes, whom they reduced to slavery.

“Then God in his wrath sent the world a savior, miraculously born . . ."

The time of the Savior was a time when the world needed a savior.

The surface of the Earth had been ravaged by the vilest war in human history. The great cities of the world had been split asunder and were flattened.

Out of one such city came a remnant of apes and men who had survived. History would report that they came in search of a place where Ape and Human might live together in friendship. But their thoughts were of survival, not of friendship.

And after survival, retribution.

One does not live peacefully with one’s former oppressors. One punishes. One seeks vengeance.

And that was their mistake. The apes had brought the ways of evil men with them. The apes were proud that they had thrown off the yoke, but they failed to realize that they had not thrown it away. They put men into it and made them live in shame.

They adopted other ways of men, too. Like men, they quarreled among themselves. Like men, they argued over directions and goals. Like men, they forgot their original purposes.

And like men, they paid homage to strength.

When the apes planted their orchards and sowed their fields, they also planted fruits of bitterness and sowed seeds of discontent.

That crop would soon be ready for harvest.

One among them might be a savior—but like other saviors before him, he had to find a way to make his people listen . . .

ONE

Aldo the gorilla knew how to save his people.

Aldo the gorilla had a plan. It was a good plan. It was right. He knew it. He smacked his lips in anticipation as he thought of it. Yes. Apes should be strong. Apes should be masters. Apes should be proud. Apes should make the Earth shake when they walked.

Apes should rule the Earth.

He knew that someday they would. And he would be the gorilla who would lead them to victory.

He sat on his horse, on a ridge, and stared out over the desert below. Somewhere out there was a city . . . or what was left of it. Perhaps there were men there, too. Dangerous men. With guns. And bombs. Apes should be ready for them. Apes should kill them.

The thought excited him. He leaned forward in the saddle eagerly, squinting and frowning. Was there something out there? The city was forbidden, but the thought was so alluring . . .

But now was not the time. Not yet, not yet.

He snorted loudly and kicked his horse in the ribs to make it move. He pulled hard on the reins and wheeled the animal around. He trotted toward the gorilla outpost farther along the ridge.

The gorillas came to attention, grumbling. They were slovenly and untidy, and that made Aldo glad—it was a sign of their strength. As he rode through their ranks, they saluted, and he grinned in response.

He kept on going and headed down the side of the ridge, away from the desert, toward a valley that was startling in its sudden lushness so close to the blasted sand. The valley was deep and peaceful. Vineyards, fields of crops, clusters of trees—Aldo grunted, restless at the sight. There was so little challenge there.

He kicked the horse again, urging it faster. He splashed through a shallow stream. Ahead lay Ape City, nestled in the midst of dense trees. It was an arboreal city, multilevel, with numerous tree houses blending in with the forest around. Vines and ladders hung from openings to permit easy entry, and there were limbs that could be climbed from one level to another. Food hung outside the windows, all vegetables and fruit. Flowers grew in suspended pots. The whole vista was one of tranquility.

Aldo sneered in annoyance. Kicking his horse once more, he galloped at full speed down into the valley, along a narrow road, through a grove of trees leading into Ape City. The wind lashed against his face; the dust of the road made his eyes water, and he squinted in reflex. But he galloped along, anyway, for the sheer brutal joy of it. The feel of the horse’s hooves pounding along the dirt was rhythmic and powerful.

He came loudly around a curve in the road and reined in suddenly. A wagon had collapsed, blocking his way. His horse reared up at the sudden stop; Aldo jerked the bridle viciously, holding the animal in fierce control. It pulled nervously to one side and whinnied in protest, but Aldo ignored it.

One of the wheels had come off the wagon. Overloaded with fruit and vegetables, it rested on the blunt end of its axle. Four human males in identical brown homespun tunics were trying to raise it; they were all unshaven and longhaired.

Off to one side stood a black man Aldo knew as MacDonald; he held a clipboard and a sheaf of papers in his hands. He was looking concerned—more about the broken wagon than about the delay he was causing Aldo.

Aldo snorted. He dismounted and strode over to the wagon. He grabbed hold of it with one hand and lifted; he gestured to the men to replace the wheel, holding the wagon up easily until they were done.

One of them, a broad-shouldered, golden-haired young man named Jake, grinned, “Thanks, Aldo. You’ve got the strength of a gorill . . . oh, sorry.” He stopped himself as he caught the darkening expression on Aldo’s face.

Was it an insult? Aldo snarled. Though Jake was tall and muscular, Aldo towered over him; he slapped Jake’s face hard with a huge, hairy hand. “Man is weak!” He slapped him again, the sound of it cracked in the air. “Man is weak! And you will address me by my rank of general!”

Jake glared at him in a long, tense silence. It was broken finally by MacDonald “Yes, General.” He said it in a deadpan monotone.

Aldo contemptuously pushed Jake aside and remounted his horse. He rode off quickly.

Jake spat after him, “That gorilla makes me sick.”

MacDonald nodded. “I’ll speak to Caesar.”

“What good will that do? Nobody can control Aldo.”

The black man shrugged. “We can try.” But he realized the truth of Jake’s words. He stared off down the road at the rapidly retreating Aldo; Aldo was dangerous, he knew it; he had seen the signs in too many men not to recognize them in the gorilla.

Aldo rode recklessly into Ape City. Apes and humans dodged out of his way as he clattered through the avenues.

In the nine years since its founding, Ape City had established a culture of its own. Apes were the dominant class, humans the servants, though not physically ill treated. Humans could be seen carrying lumber and parcels, sweeping, doing laundry, tending ape children, and building shacks below the tree houses of their masters.

Apes wore uniforms, green and black and tan. Humans wore faded tunics, the same tunics that had been worn by their ape slaves half a generation before.

Aldo pulled his horse up to a hitching post and dismounted. It was good that apes were the masters—but they weren’t firm enough with their slaves. Ape and human children were playing in the streets; apes were riding humans, tossing them things to fetch, and treating them affectionately, like puppies. That was wrong—it might teach ape children to be too lenient with humans. It might even teach apes to like humans. He growled deep in his throat at the thought.

Aldo strode through the street toward a building set on the ground. It was the ape school. Aldo hated it.

Inside, the room was large enough to permit the simultaneous teaching of two classes without either interfering with the other—unless voices were unduly raised; as sometimes happened.

In one class, an earnest but amiable bespectacled human was teaching reading and writing, speaking to a class self-segregated into two groups: in front sat child chimpanzees and child orangutans; in the rear sat the more backward gorillas—both children and adults. They looked sullen and truculent in their black leather uniforms.

The other class was less a class than what a university might have called a tutorial. Three adolescent apes—two chimpanzees and one orangutan—sat raptly at the feet of a young orangutan named Virgil. Virgil was an intellectual prodigy whose witty and fluent speech could only just keep pace with the ideas that fizzed in his remarkable brain.

Both Teacher—for that was the name the apes had given him—and Virgil were equipped with chalk stone to write on two chipped old chalkboards salvaged from the dead city. Their pupils wrote with charcoal sticks on skin parchment or papyrus. If pens, pencils, and paper still existed, they were reserved for the elite.

Aldo surveyed the scene with ill-concealed annoyance. Particularly the human-taught class. Humans teaching apes, indeed! Teacher had just finished chalking up the words “APE SHALL NEVER KILL APE” on the board. The chimp and orangutan children watched attentively. But behind them the gorillas were restless and mumbled to each other.

Teacher turned to the class. “Gorillas! Read me what I have written.”

There was glazed incomprehension and silence from the back row.

Teacher sighed. Then, more hopefully: “Orangutans? Chimpanzees?”

In unison, the front row recited, “Ape shall never kill Ape!”

Aldo moved into the classroom then to stand beside his usual place on the front bench. The class fell silent as he entered. Aldo eyed the teacher and growled, “Can Ape ever kill Man?”

There was a growl of approval from the gorillas in the back. As it subsided, Teacher said coldly, ignoring his question, “You’re late, General Aldo. Again.” He wrote something into a battered book he held.

“What are you writing?” demanded Aldo.

Teacher extended the book. “Come and read it. To the class.”

“I won’t,” the gorilla said sullenly.

“You won’t,” Teacher chided gently, “because you can’t. And you can’t, because you don’t want to learn.” He shut the book. “And it’s my duty to tell that to Caesar.”

Aldo’s growl was silenced by the word “Caesar,” which also prompted an alert little boy chimpanzee to rise to his feet. He said wistfully, “If my father were a gorilla, we’d all be learning riding instead of writing.”

The gorillas howled appreciatively. All the apes laughed, chimpanzees and orangutans too.

Teacher smiled kindly. “Cornelius,” he said to the boy chimp, “Remember you’re Caesar’s son and heir. Being a good rider won’t make you a good ruler. Although,” he added drily, “in human history, quite a number of monarchs—and military dictators—seem to have thought that was enough.” He looked at Aldo as he said this last. He turned back to the class. “Now all of you take your charcoal sticks and copy down what I’ve written. The best shall be hung from this hook on the wall.”

Aldo took his place grumbling and eyeing the teacher. “I can think of better things to hang from hooks.”

He picked up his charcoal stick clumsily and began to make marks on the papyrus. It was difficult; he looked around to see if anyone else was having problems. The chimpanzees and orangutans were writing clearly and rapidly; the other gorillas were working slowly and with difficulty. Aldo bent back to his papyrus; he pressed harder, as if that would help. The charcoal stick snapped in two. “Aaargh!” he snarled. He hated the school! He hated writing! It was a useless waste of time—it was an occupation fit only for men! And for the weaker apes, chimpanzees and orangutans! “Effete intellectuals,” he fumed; they weren’t much better than humans!

In cheerful contrast, at the classroom’s other end, the young orangutan Virgil was stimulating the minds of his three ape pupils. He was trying to exercise their brains with argument, not fill them with facts. The dialogue was quick tempoed.

“But, Virgil, can we alter destiny? Can we tamper with time?”

Virgil’s smile was mischievous. “Accept my premise, and I will prove it logically.”

“What premise?”

“That the legends are true—that Man learned to travel not only faster than sound but faster than light as well.”

“All right, we accept the premise.”

“Then imagine a musician giving a live broadcast from what was once London to what was once New York on a Wednesday. He then travels faster than light from London to New York, where he arrives on the previous Tuesday, listens to his own broadcast on Wednesday, dislikes its quality intensely, and travels back faster than light to London in time to talk himself out of giving the broadcast in the first place.”

The chimpanzees and the orangutan shouted with laughter at this dubious but invigorating idea.

On the other side of the room, Teacher heard the happy laughter and envied it; that was what teaching should be. He sighed and went on mechanically scrutinizing and stacking on the desktop the parchments that the last of the chimp and orangutan children were now submitting for his inspection, “That’s very good, Mirko. You’re dismissed.”

Cornelius was the last of the chimps to present his parchment. Teacher looked it over carefully. “Good, Cornelius . . . Oh, there’s a mistake. You’ve written a ‘B’ for the second ‘P.’ ‘APE SHALL NEVER KILL ABE.’ ” He smiled jovially, “Who’s Abe?”

There was a pause. Then Cornelius said softly, “Teacher, have you forgotten your own name?”

Teacher was startled—and then touched. His eyes became moist. His voice fell to a whisper, and he mused, almost to himself, “So many people call me ‘Teacher,’ I’d almost . . .” He smiled at the chimp. “ ‘Ape shall never kill Abe.’ Thank you, Cornelius. That was a very kind thought.” He pulled himself together with visible effort. “You’re dismissed.” Cornelius trotted out.

He stood up and looked toward the back of his class. “Gorillas! Are you done?” He stared at them as firmly as he could; they were so much like children; discipline was all they understood. It was a shame their bodies had matured before their minds. With their incredible strength to force things to their will, they had no incentive to learn; they could accomplish what they wanted by the most direct—and brutal—method.

The gorillas were hunched, motionless yet menacing, on their back-row benches. Aldo rose from his place and slouched insolently toward Teacher. He slapped his parchment on the desktop beside the others.

Teacher picked it up and scrutinized it. “General Aldo, with respect, this is barely legible and will have to be written again. Your capital ‘A’ leans over like a tent in a high wind, and your ‘K’ is . . .”

Aldo curled his lip. Glaring at Teacher, he deliberately took Cornelius’ parchment from the top of the pile and began to tear it into shreds.

Teacher shouted at him, agonized, “No, Aldo! No!”

Abruptly, every ape in the room froze, shocked into hostility. Aldo turned apoplectic. The gorillas sprang to their feet in menacing unison. Virgil, appalled, raced across the schoolroom floor. “Teacher!” he cried. “You’ve spoken the unspeakable! You’ve said ‘No’ to an ape!”

Teacher went pale, shocked with the realization of what he had done.

“Teacher!” said Virgil. “You know better—you know why a human must never, never, say ‘No’ to an ape. In all our years of slavery to men, the word ‘No’ was the one word apes were electrically conditioned to fear. Caesar has forbidden men to utter it ever. An ape may say ‘No’ to a human. But a human may never again say ‘No’ to an ape!” He stepped in closer and whispered, “Tell them you’re sorry, Abe, and go home while you still have a home to go to. I’ll try to put in a word for you with Caesar.”

Teacher nodded slowly and turned to the gorillas. “I . . . I’m sorry. The writing you destroyed was by Caesar’s son. I . . . did not want you to suffer Caesar’s anger.”

Aldo snarled at the name. “What do I care for Caesar’s anger? Let me give you a taste of mine!”

The big gorilla lifted up a block of wood and hurled it at Teacher’s head. Taking their cue, the other gorillas began to run joyfully amok, roaring and screaming. They overturned Teacher’s desk and ripped up the papyruses. And then they headed for Teacher.

Teacher ran from the classroom. The gorillas boiled after him like bees swarming out of a hive. He lurched out into the street, stumbled, caught his footing and ran. The gorillas chased after him, and the rest of the students, seeing the excitement, came tailing after.

Teacher panted as he ran—he wasn’t used to this kind of exercise—his lungs ached from the effort; he charged through stalls of fruit and vegetables. The gorillas came barreling after, upsetting baskets and tables. Aldo was in the lead, shouting and roaring. The shoppers and stall-tenders screamed as they leapt out of his way.

Teacher dodged and whirled, around a house, down a street. There, ahead of him! There was a work area where humans were plaiting screen walls for houses. Maybe he could hide there! But the gorillas had already seen him. They came crashing through the screens after him.

Teacher tried to hold onto his glasses as he ran. He took off again, this time in a different direction—toward Caesar’s house. Caesar would help him!

But he wasn’t fast enough. Aldo came roaring down on him like a freight train and threw him roughly to the ground, pushing him into the dirt.

Grinning fiercely, Aldo drew his sword from his belt. It was broad and flat and short. He raised it high over his head.

Teacher tried to raise one arm in protest. Apes and humans alike gasped in shock.

And then someone, an ape, cried, “Stop!”

All heads whirled to look—it was Caesar, standing in his doorway. He was a tall, strong chimpanzee; he had the bearing of a leader. Just behind him stood MacDonald, his chief human adviser.

The gorillas stared at Caesar. Aldo glared sullenly at him, his sword still raised over Teacher.

Caesar stepped down from the doorway, his stare fiercer than Aldo’s. “I said . . . stop . . . Aldo.”

Their eyes locked. Aldo burned with a fierce red anger, but Caesar’s quieter strength was more effective. Aldo averted his eyes. He looked around for support, but there was none from the other gorillas; they were too thoroughly cowed by Caesar’s authority. And there was certainly none from any of the chimpanzees and orangutans in the crowd; they were eyeing the gorillas with cold disdain and Caesar with love and respect.

At last, slowly, Aldo lowered his sword. But he waved in the direction of the Teacher, shouting his frustration. “He broke the Law! With his own mouth he broke the First Law!”

Caesar seemed to grow. “I am the Law,” he said sternly. “And if I find that he has broken it, I shall pass judgment. What has he done?”

Virgil pushed forward through the crowd. “I can tell you. I was there.”

Caesar turned to him, his tone softening, “Yes, Virgil . . .?”

“I was there,” Virgil said breathlessly; he too was still panting from the chase. “Teacher only . . . only . . . reverted to type under provocation. He spoke like a slave master from the old days of servitude, He spoke the negative imperative used for the conditioning of mechanical obedience.”

Caesar smothered a smile. MacDonald grinned broadly. Caesar said, “Put that in words which even Caesar can understand.”

“He said, ‘No, Aldo, no!’ ”

The crowd gasped at that, the apes in anger, the humans in fear.

MacDonald stepped forward and began to help Teacher up. “Teacher, you’re old enough to be well aware that ‘No’ is the one word a human may never say to an ape, because apes once heard it said to them a hundred times a day by humans.”

“Yes,” Teacher nodded. “I am old . . . enough.”

“Then what was the provocation?”

Teacher was uneasy. He swallowed hard. He looked back and forth between Caesar, Aldo, and MacDonald. Finally, he managed to say, “General Aldo tore up a writing exercise written especially for me by Caesar’s son. It was very good and . . . respectfully affectionate.”

Caesar turned to Aldo and confronted him. “Why did you tear it up?”

Aldo sullenly refused to answer. From the crowd, a young chimpanzee called, “Because Teacher said that the general’s writing was very bad.”

The chimpanzees and orangutans in the crowd laughed. The gorillas didn’t; they fumed in silent embarrassment, and one or two curled their lips in anger.

Caesar said, after a pause, “General Aldo is a very good rider. My son is not, though he wishes to be. But my son is a very good writer. General Aldo is not. Apes cannot excel at everything,” he said, smiling obliquely at Virgil, “with very few exceptions. That is all there is to it. The matter will be forgotten. Now go back to school.”

“The schoolroom has been wrecked, Caesar,” Virgil said. “By the gorillas.”

Aldo snorted triumphantly. “Class ended! Schoolroom closed! Now we go back to riding horses!” There was an approving bark from the gorilla group behind him, but it was quickly checked as Caesar advanced to within an inch of the general’s face.

Caesar’s voice was firm. “You and your ‘friends’ will go back and put the schoolroom in order.”

Their eyes locked. Aldo glared back, not quite totally defiant, not yet. He fumed, but he sheathed his sword.

Caesar turned on his heel and headed back toward his house, summoning MacDonald to his side with a curt gesture.

MacDonald caught up to him, frowning. This might be a good time to broach the subject of what happened on the road. He offered, “Caesar, I think that Aldo’s hatred is not confined to humans.”

Caesar was charitable; he shrugged it off. “Aldo still remembers the old days.”

MacDonald couldn’t be that charitable. “I think he’d like to bring them back.”

Caesar looked at him curiously, but he did not ask the man to explain his odd remark.

![Книга Ave, Caesar! [ Аве, Цезарь!] автора Варвара Клюева](http://itexts.net/files/books/110/oblozhka-knigi-ave-caesar-ave-cezar-246831.jpg)