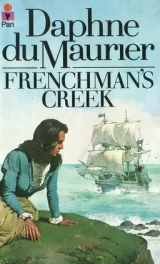

Текст книги "Frenchman's Creek"

Автор книги: Daphne du Maurier

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 3 (всего у книги 18 страниц)

"And why did you leave your master, William?"

"His life is such, at the moment, my lady, that my services are of little use to him. We decided I would do better elsewhere."

"And so you came to Navron?"

"Yes, my lady."

"And lived alone and hunted moths?"

"Your ladyship is correct."

"So that Navron is also, possibly, an escape for you as well?"

"Possibly, my lady."

"And your late master, what does he do with himself?"

"He travels, my lady."

"He makes voyages from place to place?"

"Exactly, my lady."

"Then he also, William, is a fugitive. People who travel are always fugitives."

"My master has often made the same observation, my lady. In fact I may say his life is one continual escape."

"How pleasant for him," said Dona, peeling her fruit; "the rest of us can only run away from time to time, and however much we pretend to be free, we know it is only for a little while – our hands and our feet are tied."

"Just so, my lady."

"And your master – he has no ties at all?"

"None whatever, my lady."

"I would like to meet your master, William."

"I think you would have much in common, my lady."

"Perhaps one day he will pass this way, on his travels?"

"Perhaps, my lady."

"In fact, I will withdraw my command about visitors, William. Should your late master ever call, I will not feign illness or madness or any other disease, I will receive him."

"Very good, my lady."

And looking round, for she was standing now, and he had pulled away her chair, she saw that he was smiling, but instantly his smile was gone, when he met her eyes, and his mouth was pursed in its usual button. She wandered into the garden. The air was soft and languid and warm, and away to the west the sun flung great patterns across the sky She could hear the voices of the children as Prue put them to bed. It was a time for going forth alone, a time for walking. And fetching a shawl and throwing it across her shoulders she went out of the garden and across the parkland to a stile, and a field, and a muddied lane, and the lane brought her to a cart-track, and the cart-track to a great stretch of rough wild grass, of uncultivated heath land, leading to the cliffs and the sea.

She had the urge within her to walk then to the sea, to the open sea itself, not the river even, and as the evening cooled and the sun sank in the sky, she came at length to a sloping headland where the gulls clamoured furiously at her approach, for it was the nesting season, and flinging herself down on the tussocky earth and the scrubby stones of the headland she looked out upon the sea. There was the river, away to the left, wide and shining as it met the sea, and the sea itself was still and very calm, while the setting sun dappled the water with copper and crimson. Down below, far and deep, the little waves splashed upon the rocks.

The setting sun behind her made a pathway on the sea, stretching to the far horizon, and as Dona lay and watched, her mind all drowsy and content, her heart at peace, she saw a smudge on the horizon, and presently the smudge took shape and form, and she saw the white sails of a ship. For a while it made no progress, for there was no breath upon the water, and it seemed to hang there, between sea and sky, like a painted toy. She could see the high poop-deck, and the fo'c'sle head, and the curious raking masts, and the men upon her must have had luck with their fishing for a crowd of gulls clustered around the ship, wheeling and crying, and diving to the water. Presently a little tremor of a breeze came off the headland where Dona lay, and she saw the breeze ruffle the waves below her, and travel out across the sea towards the waiting ship. Suddenly the sails caught the breeze and filled, they bellied out in the wind, lovely and white and free, the gulls rose in a mass, screaming above the masts, the setting sun caught the painted ship in a gleam of gold, and silently, stealthily, leaving a long dark ripple behind her, the ship stole in towards the land. And a feeling came upon Dona, as though a hand touched her heart, and a voice whispered in her brain, "I shall remember this." A premonition of wonder,' of fear, of sudden strange elation. She turned swiftly, smiling to herself for no reason, humming a little tune, and strode back across the hills to Navron House, skirting the mud and jumping the ditches like a child, while the sky darkened, and the moon rose, and the night wind whispered in the tall trees.

CHAPTER V

She went to bed as soon as she returned, for the walk had tired her, and she fell asleep almost at once, in spite of the curtains drawn wide, and the shining moon. And then, just after midnight it must have been, for subconsciously she had heard the stable clock strike the hour, she was awake, aware of a footstep that had crunched the gravel beneath her window. She was instantly alert, the household should be sleeping at such an hour, she was suspicious of footsteps in the night. She rose from bed then, and went to the casement, and looked out into the garden. She could see nothing beneath her, the house was in shadow, and whoever had stood there, beneath the casement, must have passed on. She waited and watched, and suddenly, from the belt of trees beyond the lawn, a figure stole into a square patch of moonlight, and looked up towards the house. She saw him cup his hands to his mouth and give a soft low whistle. At once another figure crept out from the shadowed house, he must have been sheltering just inside the window of the salon, and this second figure ran swiftly across the lawn to the man by the belt of trees, his hand raised as though in warning, and she saw that the running figure was William. Dona leant forward, screened by the curtain, her ringlets falling over her face, and she breathed quicker than usual, and her heart beat fast, for there was excitement in what she saw, there was danger – her fingers beat a little nameless tune upon the sill. The two men stood together in the patch of moonlight, and Dona saw William gesticulate with his hands, and point towards the house, at which she drew back into shadow for fear of being observed. The two continued talking, the strange man looking upward at the house also, and presently he shrugged his shoulders, spreading out his hands, as though the matter were beyond his powers of settlement, and then they both withdrew into the belt of trees, and disappeared. Dona waited, and listened, but they did not return. Then she shivered, for the breeze was cool blowing upon her thin nightgown, and she returned to bed, but could not sleep, for this new departure of William's was a mystery that must be solved.

Had she seen him walk by moonlight into the trees, alone, she would have thought little of it, there might have been a woman in Helford hamlet by the river who was not unpleasing to him, or his silent expedition might have been more innocent still, a moth-hunt at midnight. But that stealthy tread, as though he waited for a signal, and that dark figure with his cupped hands and the soft whistle, William's run across the lawn with his warning hand, these were graver problems, giving cause for worry.

She wondered if she had been a very great fool in trusting William. Anyone but herself would have dismissed him that first evening, on learning of his stewardship, how he had lived there in the house alone, without orders to do so. And that manner of his, so unlike the usual servant, that manner which intrigued and amused her, would no doubt have caused offence to most mistresses, to a Lady Godolphin. Harry would have sent him away at once – except that no doubt his manner would have been different with Harry, she felt that instinctively. And then the tobacco-jar, the volume of poetry – it was mystifying, beyond her comprehension, but in the morning she must do something, take the matter in hand, and so without having decided anything, her mind in disorder, she fell asleep at length, just as the grey morning light broke into the room.

The day was hot and shining, like its predecessor, a high golden sun in a cloudless sky, and when Dona came down her first movement was towards the belt of trees where the stranger and William had talked, and disappeared, the night before. Yes, it was as she had expected, their footsteps had made a little track through the bluebells, easy to follow, they led straight across the main pathway of the woods and down deep amongst the thickest trees. She continued for a while, the track leading downwards always, twisting, uneven, very hard to follow, and suddenly she realised that this way would lead her in time towards the river, or a branch of the river, because in the distance she caught the gleam of water that she had not suspected could be so close, for surely the river itself must be away behind her, to the left, and this thread of water she was coming to was something unknown, a discovery. She hesitated a moment, uncertain whether to continue, and then remembering the hour, and how the children would be looking for her, and William himself perhaps, for orders, she turned back, and climbed up through the woods once more, and so on to the lawns of Navron House. The matter must be postponed to a better time, later perhaps in the afternoon.

So she played with the children, and wrote a duty letter to Harry – the groom was riding back to London in a day or so, to bear him news. She sat in the salon by the wide open window, nibbling the end of her pen, for what was there to say except that she was happy in her freedom, absurdly happy, and that would be hurtful; poor Harry, he would never understand.

"The friend of your youth called upon me, one Godolphin," she wrote, "whom I found ill-favoured and pompous, and could not picture you together romping in the fields as little boys. But perhaps you did not romp, but sat upon gilt chairs and played cat's cradle. He has a growth on the end of his nose, and his wife is expecting a baby, at which I expressed sympathy. And he was in a great fuss and pother about pirates, or rather one pirate, a Frenchman, who comes by night and robs his house, and the houses of his neighbours, and all the soldiers of the west cannot catch him, which seems to me not very clever of them. So I propose setting forth myself, with a cutlass between my teeth, and when I have entrapped the rogue, who according to Godolphin is a very fierce fellow indeed, a slayer of men and a ravisher of women, I will bind him with strong cords and send him to you as a present." She yawned, and tapped her teeth with her pen, it was easy to write this sort of letter, making a jest of everything, and she must be careful not to be tender, because Harry would take horse at once and ride to her, nor must she be too cold, for that would fret him, and would also bring him.

So "Amuse yourself as you wish, and think of your figure when you take that fifth glass," she wrote, "and address yourself, if you should have the desire, to any lovely lady your sleepy eye should fall upon, I will not play the scold when I see you again.

"Your children are well, and send their love, and I send you – whatever you would wish me to send.

"Your affectionate wife, "DONA."

She folded the letter, and sealed it. Now she was free once more, and began to think how she could rid herself of William for the afternoon, for she wished ban well away before she started on her expedition. At one o'clock, over her cold meat, she know how she would do it.

"William," she said.

"My lady?"

She glanced up at him, and there was no night-hawk look about him, he was the same as always, attentive to her commands.

"William," she said, "I would like you to ride to my Lord Godolphin's manor this afternoon, bearing flowers for his lady who is unwell."

Was that a flicker of annoyance in his eye, a momentary unwillingness, a hesitation?

"You wish me to take the flowers today, my lady?"

"If you please, William."

"I believe the groom is doing nothing, my lady."

"I wish the groom to take Miss Henrietta and Master James and the nurse for a picnic, in the carriage."

"Very well, my lady."

"You will tell the gardener to cut the flowers?"

"Yes, my lady."

She said no more, and he too was silent, and she smiled to herself, for she guessed he did not wish to go. Perhaps he had another assignation with his friend, down through the woods. Well, she would keep it for him.

"Tell one of the maids to turn back my bed and draw the curtains, I shall rest this afternoon," she said, as she went from the room, and William bowed without reply.

This was a ruse to dull any fears he might have, but she was certain he was without suspicion. And so, playing her part, she went upstairs and lay down on her bed. Later she heard the carriage draw up in the courtyard, and the children's voices chattering excitedly at the sudden picnic, and then the carriage bowled away down the avenue. After a short while she heard a single horse clatter on the cobbled stones, and leaving her room, and going out on to the passage where the window looked out upon the yard, she saw William mount one of the horses, a great bunch of flowers before him on the saddle, and so ride away.

How successful the strategy, she thought, laughing to herself like a silly child on an adventure. She put on a faded gown which she would not mind tearing, and a silken handkerchief around her head, and slipped out of her own house like a thief.

She followed the track that she had found in the morning, but this time plunging down deep into the woods without hesitation. The birds were astir again, after their noonday silence, and the silent butterflies danced and fluttered, while drowsy bumble bees hummed in the warm air, winging their way to the topmost branches of the trees. Yes, there once again was the glimmer of water that had surprised her. The trees were thinning, she was coming to the bank – and there, suddenly before her for the first time, was the creek, still and soundless, shrouded by the trees, hidden from the eyes of men. She stared at it in wonder, for she had had no knowledge of its existence, this stealthy branch of the parent river creeping into her own property, so sheltered, so concealed by the woods themselves. The tide was ebbing, the water oozing away from the mud-flats, and here, where she stood, was the head of the creek itself for the stream ended in a trickle, and the trickle in a spring. The creek twisted round a belt of trees, and she began to walk along the bank, happy, fascinated, forgetting her mission, for this discovery was a pleasure quite unexpected, this creek was a source of enchantment, a new escape, better than Navron itself, a place to drowse and sleep, a lotus-land. There was a heron, standing in the shallows, solemn and grey, his head sunk in his hooded shoulders, and beyond him a little oyster-catcher pattered in the mud, and then, weird and lovely, a curlew called, and rising from the bank, flew away from her down the creek. Something, not herself, disturbed the birds, for the heron rose slowly, flapping his slow wings, and followed the curlew, and Dona paused a moment, for she too had heard a sound, a sound of tapping, of hammering.

She went on, coming to the corner where the creek turned, and then she paused, withdrawing instinctively to the cover of the trees, for there before her, where the creek suddenly widened, forming a pool, lay a ship at anchor – so close that she could have tossed a biscuit to the decks. She recognised it at once. This was the ship she had seen the night before, the painted ship on the horizon, red and golden in the setting sun. There were two men slung over the side, chipping at the paint, this was the sound of hammering she had heard. It must be deep water where the ship lay, a perfect anchorage, for on either side the mud banks rose steeply and the tide ran away, frothing and bubbling, while the creek itself twisted again and turned, running towards the parent river out of sight. A few yards from where she stood was a little quay. There was tackle there, and blocks, and ropes; they must be making repairs. A boat was tide alongside, but no one was in it.

But for the two men chipping at the side of the ship all was still, the drowsy stillness of a summer afternoon. No one would know, thought Dona, no one could tell, unless they had walked as she had done, down from Navron House, that a ship lay at anchor in this pool, shrouded as it was by the trees, and hidden from the open river.

Another man crossed the deck and leant over the bulwark, gazing down at his fellows. A little smiling man, like a monkey, and he carried a lute in his hands. He swung himself up on the bulwark, and sat cross-legged, and began to play the strings. The two men looked up at him, and laughed, as he strummed a careless, lilting air, and then he began to sing, softly at first, then a little louder, and Dona, straining to catch the words, realised with a sudden wave of understanding, and her heart thumping, that the man was singing in French.

Then she knew, then she understood – her hands went clammy, her mouth felt dry and parched, and she felt, for the first time in her life, a funny strange spasm of fear.

This was the Frenchman's hiding-place – that was his ship.

She must think rapidly, make a plan, make some use of her knowledge; how obvious it was now, this silent creek, this perfect hiding-place, no one would ever know, so remote, so silent, so still – something must be done, she would have to say something, tell someone.

Or need she? Could she go away now, pretend she had not seen the ship, forget about it, or pretend to forget it – anything so that she need not be involved, for that would mean a breaking up of her peace, a disturbance, soldiers tramping through the woods, people arriving, Harry from London – endless complications, and Navron no more a sanctuary. No, she would say nothing, she would creep away now, back to the woods and the house, clinging to her guilty knowledge, telling no one, letting the robberies continue – what did it matter – Godolphin and his turnip friends must put up with it, the country must suffer, she did not care.

And then, even as she turned to slip away amongst the trees, a figure stepped out from behind her, from the woods, and throwing his coat over her head blinded her, pinning her hands to her sides, so that she could not move, could not struggle, and she fell down at his feet, suffocated, helpless, knowing she was lost.

CHAPTER VI

Her first feeling was one of anger, of blind unreasoning anger. How dare anyone treat her thus, she thought, truss her up like a fowl, and carry her to the quay. She was thrown roughly onto the bottom boards °f the boat, and the man who had knocked her down took the paddles and pushed out towards the ship. He gave a cry – a sea-gull's cry – and called something in a patois which she could not understand to his companions on the ship. She heard them laugh in reply, and the fellow with the lute struck up a merry little jig, as though in mockery.

She had freed herself now from the strangling coat, and looked up at the man who had struck her. He spoke to her in French and grinned. He had a merry twinkle in his eye, as though her capture were a game, an amusing jest of a summer's afternoon, and when she frowned at him haughtily, determined to be dignified, he pulled a solemn face, feigning fear, and pretended to tremble.

She wondered what would happen if she raised her voice and shouted for help – would anyone hear her, would it be useless?

Somehow she knew she could not do this, women like herself did not scream. They waited, they planned escape. She could swim, it would be possible later perhaps to get away from the ship, lower herself over the side, perhaps when it was dark. What a fool she had been, she thought, to linger there an instant, when she knew that the ship was the Frenchman. How deserving of capture she was, after all, and how infuriating to be placed in such a position – ridiculous, absurd – when a quiet withdrawal to the trees and back to Navron would have been so easy. They were passing now under the stern of the ship, beneath the high poop-deck and the scrolled windows, and there was the name, written with a flourish, in gold letters La Mouette. She wondered what it meant, she could not remember, her French was hazy suddenly, and now he was pointing to the ladder over the side of the ship, and the men on deck were crowding round, grinning, familiar – damn their eyes – to watch her mount. She managed the ladder well, determined to give them no cause for mockery, and shaking her head she swung herself down to the deck, refusing their offers of assistance.

They began to chatter to her in this patois she could not follow – it must be Breton, had not Godolphin said something about the ship slipping across to the opposite coast – and they kept smiling and laughing at her in a familiar, idiotic way that she found infuriating, for it went ill with the heroic dignified part she wished to play. She folded her arms, and looked away from them, saying nothing. Then the first man appeared again – he had gone to warn their leader she supposed, the captain of this fantastic vessel – and beckoned her to follow him.

It was all different from what she had expected. These men were like children, enchanted with her appearance, smiling and whistling, and she had believed pirates to be desperate creatures, with rings in their ears and knives between their teeth.

The ship was clean – she had imagined a craft filthy and stained, and evil-smelling – there was no disorder about it, the paint was fresh and gay, the decks scrubbed like a man-o'-war and from the forward part of the ship, where the men lived she supposed, came the good hunger-making smell of vegetable soup. And now the man was leading her through a swinging door and down some steps, and he knocked on a further door, and a quiet voice bade him enter. Dona stood on the threshold, blinking a little, for the sun was streaming through the windows in the stern, making water patterns on the light wood panelling. Once again she felt foolish, disconcerted, for the cabin was not the dark hole she had imagined, full of empty bottles and cutlasses, but a room – like a room in a house – with chairs, and a polished table, and little paintings of birds upon the bulkheads. There was something restful about it, restful yet austere, the room of someone who was sufficient to himself. The man who had taken her to the cabin withdrew, closing the door quietly, and the figure at the polished table continued with his writing, taking no notice of her entrance. She watched him furtively, aware of sudden shyness and hating herself for it, she, Dona, who was never shy, who cared for nothing and for no one. She wondered how long he would keep her standing there; it was unmannerly, churlish, and yet she knew she could not be the first to speak. She thought of Godolphin suddenly, Godolphin with his bulbous eyes and the growth on the end of his nose, and his fears for his women-folk; what would he say if he could see her now, alone in the cabin with the terrible Frenchman?

And the Frenchman continued writing, and Dona went on standing by the door. She realised now what made him different from other men. He wore his own hair, as men used to do, instead of the ridiculous curled wigs that had become the fashion, and she saw at once how suited it was to him, how impossible it would be for him to wear it in any other way.

How remote he was, how detached, like some student in college studying for an examination; he had not even bothered to raise his head when she came into his presence, and what was he scribbling there anyway that was so important? She ventured to step forward closer to the table, so that she could see, and now she realised he was not writing at all, he was drawing, he was sketching, finely, with great care, a heron standing on the mud-flats, as she had seen a heron stand, ten minutes before.

Then she was baffled, then she was at a loss for words, for thought, even, for pirates were not like this, at least not the pirates of her imagination, and why could he not play the part she had assigned to him, become an evil, leering fellow, full of strange oaths, dirty, greasy-handed, not this grave figure seated at the polished table, holding her in contempt?

Then he spoke at last, only the very faintest trace of accent marking his voice, and still he did not look at her, but went on with his drawing of the heron.

"It seems you have been spying upon my ship," he said.

Immediately she was stung to anger – she spying! Good God, what an accusation!

"On the contrary," she said, speaking coldly, clearly, in the boyish voice she used to servants. "On the contrary, it seems your men have been trespassing upon my land."

He glanced up at once, and rose to his feet – he was tall, much taller than she had imagined – and into his dark eyes came a look surely of recognition, like a sudden flame, and he smiled slowly, as if in secret.

"My very humble apologies," he said. "I had not realised that the lady of the manor had come to visit me in person."

He reached forward for a chair, and she sat down, without a word. He went on looking at her, that glance of recognition, of secret amusement in his eyes, and he leant back in his chair, crossing his legs, biting the end of his quill.

"Was it by your orders that I was seized and brought here?" she said, because surely something must be said, and he would do nothing but look her up and down in this singular fashion.

"My men are told to bind anyone who ventures to the creek," he said. "As a rule we have no trouble. You have been more bold than the inhabitants, and, alas, have suffered from that boldness. You are not hurt, are you, or bruised?"

"No," she said shortly.

"What are you complaining about then?"

"I am not used to being treated in such a manner," she said, angry again, for he was making her look a fool.

"No, of course not," he said quietly, "but it will do you no harm."

God almighty, what insolence, what damned impertinence. Her anger only amused him though, for he went on tilting his chair and smiling, biting the end of his quill.

"What do you propose to do with me?" she said.

"Ah! there you have me," he replied, putting down his pen. "I must look up my book of rules." And he opened a drawer in the table and took out a volume, the pages of which he proceeded to turn slowly, with great gravity.

"Prisoners – method of capture – questioning – detainment – their treatment – etc., etc.," he read aloud, "h'm, yes, it is all here, but unfortunately these notes relate to the capture and treatment of male prisoners. I have made no arrangements apparently to deal with females. It is really most remiss of me."

She thought of Godolphin again, and his fears, and in spite of her annoyance she found herself smiling, remembering his words: "As the fellow is a Frenchman it is only a matter of time."

His voice broke in upon her thoughts. "That is better," he said. "Anger does not become you, you know. Now you are beginning to look more like yourself." "What do you know of me?" she said.

He smiled again, tilting forward on his chair. "The Lady St. Columb," he said, "the spoilt darling of the Court. The Lady Dona who drinks in the London taverns with her husband's friends. You are quite a celebrity, you know."

She found herself flushing scarlet, stung by the irony of his words, his quiet contempt.

"That's over," she said, "finished and done with."

"For the time being, you mean."

"No, forever."

He began whistling softly to himself, and reaching for his drawing continued to play with it, sketching in the background.

"When you have been at Navron a little while you will tire of it," he said, "and the smells and sounds of London will call to you again. You will remember this mood as a passing thing."

"No," she said.

But he did not answer, he went on with his drawing.

She watched him, stung with curiosity, for he drew well, and she began to forget she was his prisoner and that they should be at enmity with one another.

"That heron was standing on the mud, by the head of the creek," she said, "I saw him, just now, before I came to the ship."

"Yes," he answered, "he is always there, when the tide ebbs. It is one of his feeding grounds. He nests some distance away though, nearer to Gweek, up the main channel. What else did you see?"

"An oyster-catcher, and another bird, a curlew, I think it was."

"Oh, yes," he said, "they would be there too. I expect the hammering drove them away."

"Yes," she said.

He continued his little tuneless whistle, drawing the while, and she watched him, thinking how natural it was, how effortless and easy, to be sitting here, in this cabin, on this ship, side by side with the Frenchman, while the sun streamed in through the windows and the ebb-tide bubbled round the stern. It was funny, like, a dream, like something she had always known would happen, as though this was a scene in a play, in which she must act a part, and the curtain had now lifted, and someone had whispered: "Here – this is where you go on."

"The night-jars have started now, in the evenings," he said, "they crouch in the hillside, farther down the creek. They are so wary though, it's almost impossible to get really close."

"Yes," she said.

"The creek is my refuge, you know," he said, glancing up at her, and then away again. "I come here to do nothing. And then, just before the idleness gets the better of me, I have the strength of mind to tear myself away, to set sail again."

"And commit acts of piracy against my countrymen?" she said.

"And commit acts of piracy against your countrymen," he echoed.

He finished his drawing, and put it away, and then rose to his feet, stretching his arms above his head.

"One day they will catch you," she said.

"One day… perhaps," he said, and he wandered to the window in the stern, and looked out, his back turned to her.

"Come and look," he said, and she got up from her chair and went and stood beside him, and they looked down to the water, where there floated a great cluster of gulls, nosing for scraps.