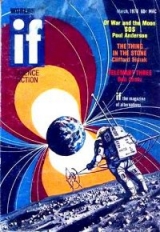

Текст книги "The Thing in the Stone"

Автор книги: Clifford D. Simak

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 3 (всего у книги 4 страниц)

The wind was blowing harder. The branches of the trees were waving and a storm of leaves was banking down the hillside, flying with the ice and snow.

From where he squatted he could see the topmost branches of the clump of birches which grew atop the mound just beyond where the cave tree had stood. And these branches, it seemed to him, were waving about far more violently than could be accounted for by wind. They were lashing wildly from one side to the other and even as he watched they seemed to rise higher in the air, as if the trees, in some great agony, were raising their branches far above their heads in a plea for mercy.

Daniels crept forward on his hands and knees and thrust his head out to see down to the base of the cliff.

Not only the topmost branches of the clump of birches were swaying but the entire clump seemed to be in motion, thrashing about as if some unseen hand were attempting to wrench it from the soil. But even as he thought this, he saw that the ground itself was in agitation, heaving up and out. It looked exactly as if someone had taken a time-lapse movie of the development of a frost boil with the film being run at a normal speed. The ground was heaving up and the clump was heaving with it. A shower of gravel and other debris was flowing down the slope, loosened by the heaving of the ground. A boulder broke away and crashed down the hill, crushing brush and shrubs and leaving hideous scars.

Daniels watched in horrified fascination.

Was he witnessing, he wondered, some wonderfully speeded-up geological process? He tried to pinpoint exactly what kind of process it might be. He knew of one that seemed to fit. The mound kept on heaving upward, splintering outward from its center. A great flood of loose debris was now pouring down the slope, leaving a path of brown in the whiteness of the fallen snow. The clump of birch tipped over and went skidding down the slope and out of the place where it had stood a shape emerged.

Not a solid shape, but a hazy one that looked as if someone had scraped some stardust from the sky and molded it into a ragged, shifting form that did not set into any definite pattern, that kept shifting and changing, although it did not entirely lose all resemblance to the shape in which it might originally have been molded. It looked as a loose conglomeration of atoms might look if atoms could be seen. It sparkled softly in the grayness of the day and despite its seeming insubstantiality it apparently had some strength—for it continued to push itself from the shattered mound until finally it stood free of it.

Having freed itself, it drifted up toward the ledge.

Strangely, Daniels felt no fear, only a vast curiosity. He tried to make out what the drifting shape was but he could not be sure.

As it reached the ledge and moved slightly above it he drew back to crouch within the cave. The shape drifted in a couple of feet or so and perched on the ledge—either perched upon it or floated just above it.

You spoke, the sparkling shape said to Daniels.

It was not a question, nor a statement either, really, and it was not really speaking. It sounded exactly like the talk Daniels had heard when he’d listened to the stars.

You spoke to it, said the shape, as if you were a friend (although the word was not friend but something else entirely, something warm and friendly). You offered help to it. Is there help that you can give?

That question at least was clear enough.

“I don’t know,” said Daniels. “Not right now, there isn’t. But in a hundred years from now, perhaps—are you hearing me? Do you know what I am saying?”

You say there can be help, the creature said, but only after time. Please, what is that time?

“A hundred years,” said Daniels. “When the planet goes around the star one hundred times.”

One hundred? asked the creature.

Daniels held up the fingers of both hands. “Can you see my fingers? The appendages on the tips of my arms?”

See? the creature asked.

“Sense them. Count them.”

Yes, I can count them.

“They number ten,” said Daniels. “Ten times that many of them would be a hundred.”

It is no great span of time, the creature said. What kind of help by then?

“You know genetics? How a creature comes into being, how it knows what kind of thing it is to become, how it grows, how it knows how to grow and what to become. The amino acids that make up the ribonucleic acids and provide the key to the kind of cells it grows and what their functions are.”

I do not know your terms, the creature said, but I understand. So you know of this? You are not, then, a brute wild creature, like the other life that simply stands and the others that burrow in the ground and climb the standing life forms and run along the ground.

It did not come out like this, of course. The words were there—or meanings that had the feel of words—but there were pictures as well of trees, of burrowing mice, of squirrels, of rabbits, of the lurching woodchuck and the running fox.

“Not I,” said Daniels, “but others of my kind. I know but little of it. There are others who spend all their time in the study of it.”

The other perched on the ledge and said nothing more. Beyond it the trees whipped in the wind and the snow came whirling down, Daniels huddled back from the ledge, shivered in the cold and wondered if this thing upon the ledge could be hallucination.

But as he thought it, the thing began to talk again, although this time it did not seem to be talking to him. It talked, rather, as the creature in the stone had talked, remembering. It communicated, perhaps, something he was not meant to know, but Daniels had no way of keeping from knowing. Sentience flowed from the creature and impacted on his mind, filling all his mind, barring all else, so that it seemed as if it were he and not this other who was remembering.

5

First there was space—endless, limitless space, so far from everything, so brutal, so frigid, so uncaring that it numbed the mind, not so much from fear or loneliness as from the realization that in this eternity of space the thing that was himself was dwarfed to an insignificance no yardstick could measure. So far from home, so lost, so directionless—and yet not entirely directionless, for there was a trace, a scent, a spoor, a knowing that could not be expressed or understood or even guessed at in the framework of humanity; a trace, a scent, a spoor that showed the way, no matter how dimly or how hopelessly, that something else had taken at some other time. And a mindless determination, an unflagging devotion, a primal urgency that drove him on that faint, dim trail, to follow where it might lead, even to the end of time or space, or the both of them together, never to fail or quit or falter until the trail had finally reached an end or had been wiped out by whatever winds might blow through empty space.

There was something here. Daniels told himself, that, for all its alienness, still was familiar, a factor that should lend itself to translation into human terms and thus establish some sort of link between this remembering alien mind and his human mind.

The emptiness and the silence, the cold uncaring went on and on and on and there seemed no end to it. But he came to understand there had to be an end to it and that the end was here, in these tangled hills above the ancient river. And after the almost endless time of darkness and uncaring, another almost endless time of waiting, of having reached the end, of having gone as far as one might go and then settling down to wait with an ageless patience that never would grow weary.

You spoke of help, the creature said to him. Why help? You do not know this other. Why should you want to help?

“It is alive,” said Daniels. “It’s alive and I’m alive and is that not enough?”

I do not know, the creature said.

“I think it is,” said Daniels.

And how could you help?

“I’ve told you about this business of genetics. I don’t know if I can explain—”

I have the terms from your mind, the creature said. The genetic code.

“Would this other one, the one beneath the stone, the one you guard—”

Not guard, the creature said. The one I wait for.

“You will wait for long.”

I am equipped for waiting. I have waited long. I can wait much longer.

“Someday,” Daniels said, “the stone will erode away. But you need not wait that long. Does this other creature know its genetic code?”

It knows, the creature said. It knows far more than I.

“But all of it,” insisted Daniels. “Down to the last linkage, the final ingredient, the sequences of all the billions of—”

It knows, the creature said. The first requisite of all life is to understand itself.

“And it could—it would—be willing to give us that information, to supply us its genetic code?”

You are presumptuous, said the sparkling creature (although the word was harder than presumptuous). That is information no thing gives another. It is indecent and obscene (here again the words were not exactly indecent and obscene). It involves the giving of one’s self into another’s hands. It is an ultimate and purposeless surrender.

“Not surrender,” Daniels said. “A way of escaping from its imprisonment. In time, in the hundred years of which I told you, the people of my race could take that genetic code and construct another creature exactly like the first. Duplicate it with exact preciseness.”

But it still would be in stone.

“Only one of it. The original one. That original could wait for the erosion of the rock. But the other one, its duplicate, could take up life again.”

And what, Daniels wondered, if the creature in the stone did not wish for rescue? What if it had deliberately placed itself beneath the stone? What if it simply sought protection and sanctuary? Perhaps, if it wished, the creature could get out of where it was as easily as this other one—or this other thing—had risen from the mound.

No, it cannot, said the creature squatting on the ledge. I was careless. I went to sleep while waiting and I slept too long.

And that would have been a long sleep, Daniels told himself. A sleep so long that dribbling soil had mounded over it, that fallen boulders, cracked off the cliff by frost, had been buried in the soil and that a clump of birch had sprouted and grown into trees thirty feet high. There was a difference here in time rate that he could not comprehend.

But some of the rest, he told himself, he had sensed—the devoted loyalty and the mindless patience of the creature that tracked another far among the stars. He knew he was right, for the mind of that other thing, that devoted star-dog perched upon the ledge, came into him and fastened on his mind and for a moment the two of them, the two minds, for all their differences, merged into a single mind in a gesture of fellowship and basic understanding, as if for the first time in what must have been millions of years this baying hound from outer space had found a creature that could understand its duty and its purpose.

“We could try to dig it out,” said Daniels. “I had thought of that, of course, but I was afraid that it would be injured. And it would be hard to convince anyone—”

No, said the creature, digging would not do. There is much you do not understand. But this other proposal that you have, that has great merit. You say you do not have the knowledge of genetics to take this action now. Have you talked to others of your kind?

“I talked to one,” said Daniels, “and he would not listen. He thought I was mad. But he was not, after all, the man I should have spoken to. In time I could talk with others but not right now. No matter how much I might want to—I can’t. For they would laugh at me and I could not stand their laughter. But in a hundred years or somewhat less I could—”

But you will not exist a hundred years, said the faithful dog. You are a short-lived species. Which might explain your rapid rise. All life here is short-lived and that gives evolution a chance to build intelligence. When I first came here I found but mindless entities.

“You are right,” said Daniels. “I can live no hundred years. Even from the very start, I could not live a hundred years, and better than half of my life is gone. Perhaps much more than half of it. For unless I can get out of this cave I will be dead in days.”

Reach out, said the sparkling one. Reach out and touch me, being.

Slowly Daniels reached out. His hand went through the sparkle and the shine and he had no sense of matter—it was as if he’d moved his hand through nothing but air.

You see, the creature said, I cannot help you. There is no way for our energies to interact. I am sorry, friend. (it was not friend, exactly, but it was good enough, and it might have been, Daniels thought, a great deal more than friend.)

“I am sorry, too,” said Daniels. “I would like to live.”

Silence fell between them, the soft and brooding silence of a snow-laden afternoon with nothing but the trees and the rock and the hidden little life to share the silence with them.

It had been for nothing, then, Daniels told himself, this meeting with a creature from another world. Unless he could somehow get off this ledge there was nothing he could do. Although why he should so concern himself with the rescue of the creature in the stone he could not understand. Surely whether he himself lived or died should be of more importance to him than that his death would foreclose any chance of help to the buried alien.

“But it may not be for nothing,” he told the sparkling creature. “Now that you know—”

My knowing, said the creature, will have no effect. There are others from the stars who would have the knowledge—but even if I could contact them they would pay no attention to me. My position is too lowly to converse with the greater ones. My only hope would be people of your kind and, if I’m not mistaken, only with yourself. For I catch the edge of thought that you are the only one who really understands. There is no other of your race who could even be aware of me.

Daniels nodded. It was entirely true. No other human existed whose brain had been jumbled so fortunately as to have acquired the abilities he held. He was the only hope for the creature in the stone and even such hope as he represented might be very slight, for before it could be made effective he must find someone who would listen and believe. And that belief must reach across the years to a time when genetic engineering was considerably advanced beyond its present state.

If you could manage to survive the present this, said the hound from outer space, I might bring to bear certain energies and techniques—sufficiently for the project to be carried through. But, as you must realize, I cannot supply the means to survive this crisis.

“Someone may come along,” said Daniels. “They might hear me if I yelled every now and then.”

He began yelling every now and then and received no answer. His yells were muffled by the storm and it was unlikely, he knew, that there would be men abroad at a time like this. They’d be safe beside their fires.

The sparkling creature still perched upon the ledge when Daniels slumped back to rest. The other made an indefinite sort of shape that seemed much like a lopsided Christmas tree standing in the snow.

Daniels told himself not to go to sleep. He must close his eyes only for a moment, then snap them open—he must not let them stay shut for then sleep would come upon him. He should beat his arms across his chest for warmth—but his arms were heavy and did not want to work.

He felt himself sliding prone to the cave floor and fought to drive himself erect. But his will to fight was thin and the rock was comfortable. So comfortable, he thought, that he could afford a moment’s rest before forcing himself erect. And the funny thing about it was that the cave floor had turned to mud and water and the sun was shining and he seemed warm again.

He rose with a start and he saw that he was standing in a wide expanse of water no deeper than his ankles, black ooze underfoot.

There was no cave and no hill in which the cave might be. There was simply this vast sheet of water and behind him, less than thirty feet away, the muddy beach of a tiny island—a muddy, rocky island, with smears of sickly green clinging to the rocks.

He was in another time, he knew, but not in another place. Always when he slipped through time he came to rest on exactly the same spot upon the surface of the earth that he had occupied when the change had come.

And standing there he wondered once again, as he had many times before, what strange mechanism operated to shift him bodily in space so that when he was transported to a time other than his own he did not find himself buried under, say, twenty feet of rock or soil or suspended twenty feet above the surface.

But now, he knew, was no time to think or wonder. By a strange quirk of circumstance he was no longer in the cave and it made good sense to get away from where he was as swiftly as he could. For if he stayed standing where he was he might snap back unexpectedly to his present and find himself still huddled in the cave.

He turned clumsily about, his feet tangling in the muddy bottom, and lunged towards the shore. The going was hard but he made it and went up the slimy stretch of muddy beach until he could reach the tumbled rocks and could sit and rest.

His breathing was difficult. He gulped great lungfuls and the air had a strange taste to it, not like normal air.

He sat on the rock, gasping for breath, and gazed out across the sheet of water shining in the high, warm sun. Far out he caught sight of a long, humping swell and watched it coming in. When it reached the shore it washed up the muddy incline almost to his feet. Far out on the glassy surface another swell was forming.

The sheet of water was greater, he realized, than he had first imagined. This was also the first time in his wanderings through the past that he had ever come upon any large body of water. Always before he had emerged on dry land whose general contours had been recognizable—and there had always been the river flowing through the hills.

Here nothing was recognizable. This was a totally different place and there could be no question that he had been projected farther back in time than ever before—back to the day of some great epicontinental sea, back to a time, perhaps, when the atmosphere had far less oxygen than it would have in later eons. More than likely, he thought, he was very close in time to that boundary line where life for a creature such as he would be impossible. Here there apparently was sufficient oxygen, although a man must pump more air into his lungs than he would normally. Go back a few million years and the oxygen might fall to the point where it would be insufficient. Go a little farther back and find no free oxygen at all.

Watching the beach, he saw the little things skittering back and forth, seeking refuge in spume-whitened piles of drift or popping into tiny burrows. He put his hand down on the rock on which he sat and scrubbed gently at a patch of green. It slid off the rock and clung to his flesh, smearing his palm with a slimy gelatinous mess that felt disgusting and unclean.

Here, then, was the first of life to dwell upon the land—scarcely creatures as yet, still clinging to the edge of water, afraid and unequipped to wander too far from the side of that wet and gentle mother which, from the first beginning, had nurtured life. Even the plants still clung close to the sea, existing, perhaps, only upon rocky surfaces so close to the beach that occasional spray could reach them.

Daniels found that now he did not have to gasp quite so much for breath. Plowing through the mud up to the rock had been exhausting work in an oxygen-poor atmosphere. But sitting quietly on the rocks, he could get along all right.

Now that the blood had stopped pounding in his head he became aware of silence. He heard one sound only, the soft lapping of the water against the muddy beach, a lonely effect that seemed to emphasize rather than break the silence.

Never before in his life, he realized, had he heard so little sound. Back in the other worlds he had known there had been not one noise, but many, even on the quietest days. But here there was nothing to make a sound—no trees, no animals, no insects, no birds—just the water running to the far horizon and the bright sun in the sky.

For the first time in many months he knew again that sense of out-of-placeness, of not belonging, the feeling of being where he was not wanted and had no right to be, an intruder in a world that was out of bounds, not for him alone but for anything that was more complex or more sophisticated than the little skitterers on the beach.

He sat beneath the alien sun, surrounded by the alien water, watching the little things that in eons yet to come would give rise to such creatures as himself, and tried to feel some sort of kinship to the skitterers. But he could feel no kinship.

And suddenly in this place of one-sound-only there came a throbbing, faint but clear and presently louder, pressing down against the water, beating at the little island—a sound out of the sky.

Daniels leaped to his feet and looked up and the ship was there, plummeting down toward him. But not a ship of solid form, it seemed—rather a distorted thing, as if many planes of light (if there could be such things as planes of light) had been slapped together in a haphazard sort of way.

A throbbing came from it that set the atmosphere to howling and the planes of light kept changing shape or changing places, so that the ship, from one moment to the next, never looked the same.

It had been dropping fast to start with but now it was slowing down as it continued to fall, ponderously and with massive deliberation, straight toward the island.

Daniels found himself crouching, unable to jerk his eyes and senses away from this mass of light and thunder that came out of the sky.

The sea and mud and rock, even in the full light of the sun, were flickering with the flashing that came from the shifting of the planes of light. Watching it through eyes squinted against the flashes, Daniels saw that if the ship were to drop to the surface it would not drop upon the island, as he first had feared, but a hundred feet or so offshore.

Not more than fifty feet above the water the great ship stopped and hovered and a bright thing came from it. The object hit the water with a splash but did not go under, coming to rest upon the shallow, muddy bottom of the sea, with a bit less than half of it above the surface. It was a sphere, a bright and shiny globe against which the water lapped, and even with the thunder of the ship beating at his ears, Daniels imagined he could hear the water lapping at the sphere.

Then a voice spoke above this empty world, above the throbbing of the ship, the imagined lapping sound of water, a sad, judicial voice—although it could not have been a voice, for any voice would have been too puny to be heard. But the words were there and there was no doubt of what they said:

Thus, according to the verdict and the sentence, you are here deported and abandoned upon this barren planet, where it is most devoutly hoped you will find the time and opportunity to contemplate your sins and especially the sin of (and here were words and concepts Daniels could not understand, hearing them only as a blur of sound—but the sound of them, or something in the sound of them, was such as to turn his blood to ice and at the same time fill him with a disgust and a loathing such as he’d never known before). It is regrettable, perhaps, that you are immune to death, for much as we might detest ourselves for doing it, it would be a kinder course to discontinue you and would serve better than this course to exact our purpose, which is to place you beyond all possibility of ever having contact with any sort of life again.. Here, beyond the farthest track of galactic intercourse, on this uncharted planet, we can only hope that our purpose will be served. And we urge upon you such self-examination that if, by some remote chance, in some unguessed time, you should be freed through ignorance or malice, you shall find it within yourself so to conduct your existence as not to meet or merit such fate again. And now, according to our law, you may speak any final words you wish.

The voice ceased and after a while came another. And while the terminology was somewhat more involved than Daniels could grasp their idiom translated easily into human terms.

Go screw yourself, it said.

The throbbing deepened and the ship began to move straight up into the sky. Daniels watched it until the thunder died and the ship itself was a fading twinkle in the blue.

He rose from his crouch and stood erect, trembling and weak. Groping behind him for the rock, he found it and sat down again.

Once again the only sound was the lapping of the water on the shore. He could not hear, as he had imagined that he could, the water against the shining sphere that lay a hundred feet offshore. The sun blazed down out of the sky and glinted on the sphere and Daniels found that once again he was gasping for his breath.

Without a doubt, out there in the shallow water, on the mudbank that sloped up to the island, lay the creature in the stone. And how then had it been possible for him to be transported across the hundreds of millions of years to this one microsecond of time that held the answer to all the questions he had asked about the intelligence beneath the limestone? It could not have been sheer coincidence, for this was coincidence of too large an order ever to come about. Had he somehow, subconsciously, gained more knowledge than he had been aware of from the twinkling creature that had perched upon the ledge? For a moment, he remembered, their minds had met and mingled—at that moment had there occurred a transmission of knowledge, unrecognized, buried in some corner of himself? Or was he witnessing the operation of some sort of psychic warning system set up to scare off any future intelligence that might be tempted to liberate this abandoned and marooned being? And what about the twinkling creature? Could some hidden, unguessed good exist in the thing imprisoned in the sphere—for it to have commanded the loyalty and devotion of the creature on the ledge beyond the slow erosion of geologic ages? The question raised another: What were good and evil? Who was there to judge?

The evidence of the twinkling creature was, of course, no evidence at all. No human being was so utterly depraved that he could not hope to find a dog to follow him and guard him even to the death.

More to wonder at was what had happened within his own jumbled brain that could send him so unerringly to the moment of a vital happening. What more would he find in it to astonish and confound him? How far along the path to ultimate understanding might it drive him? And what was the purpose of that driving?

He sat on the rock and gasped for breath. The sea lay flat and calm beneath the blazing sun, its only motion the long swells running in to break around the sphere and on the beach. The little skittering creatures ran along the mud and he rubbed his palm against his trouser leg, trying to brush off the green and slimy scum.

He could wade out, he thought, and have a closer look at the sphere lying in the mud. But it would be a long walk in such an atmosphere and he could not chance it—for he must be nowhere near the cave up in that distant future when he popped back to his present.

Once the excitement of knowing where he was, the sense of out-of-placeness, had worn off, this tiny mud-flat island was a boring place. There was nothing but the sky and sea and the muddy beach; there was nothing much to look at. It was a place, he thought, where nothing ever happened, or was about to happen once the ship had gone away and the great event had ended. Much was going on, of course, that in future ages would spell out to quite a lot—but it was mostly happening out of sight, down at the bottom of this shallow sea. The skittering things, he thought, and the slimy growth upon the rock were hardy, mindless pioneers of this distant day—awesome to look upon and think about but actually not too interesting.

He began drawing aimless patterns in the mud with the toe of one boot. He tried to make a tic-tac-toe layout but so much mud was clinging to his toe that it didn’t quite come out.

And then, instead of drawing in the mud, he was scraping with his toe in fallen leaves, stiff with frozen sleet and snow.

The sun was gone and the scene was dark except for a glow from something in the woods just down the hill from him. Driving sheets of snow swirled into his face and he shivered. He pulled his jacket close about him and began to button it. A man, he thought, could catch his death of cold this way, shifting as quickly as he had shifted from a steaming mudbank to the whiplash chill of a northern blizzard.

The yellow glow still persisted on the slope below him and he could hear the sound of human voices. What was going on? He was fairly certain of where he was, a hundred feet or so above the place where the cliff began—there should be no one down there; there should not be a light.

He took a slow step down the hill, then hesitated. He ought not to be going down the hill—he should be heading straight for home. The cattle would be waiting at the barnyard gate, hunched against the storm, their coats covered with ice and snow, yearning for the warmth and shelter of the barn. The pigs would not have been fed, nor the chickens either. A man owed some consideration to his livestock.

But someone was down there, someone with a lantern, almost on the lip of the cliff. If the damn fools didn’t watch out, they could slip and go plunging down into a hundred feet of space. Coon hunters more than likely, although this was not the kind of night to be out hunting coon. The coons would all be denned up.

But whoever they might be, he should go down and warn them.