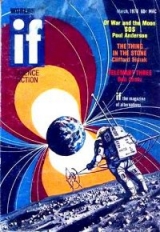

Текст книги "The Thing in the Stone"

Автор книги: Clifford D. Simak

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 4 страниц)

The Thing in the Stone

by Clifford D. Simak

1

He walked the hills and knew what the hills had seen through geologic time. He listened to the stars and spelled out what the stars were saying. He had found the creature that lay imprisoned in the stone. He had climbed the tree that in other days had been climbed by homing wildcats to reach the den gouged by time and weather out of the cliff’s sheer face. He lived alone on a worn-out farm perched on a high and narrow ridge that overlooked the confluence of two rivers. And his next-door neighbor, a most ill-favored man, drove to the county seat, thirty miles away, to tell the sheriff that this reader of the hills, this listener to the stars was a chicken thief.

The sheriff dropped by within a week or so and walked across the yard to where the man was sitting in a rocking chair on a porch that faced the river hills. The sheriff came to a halt at the foot of the stairs that ran up to the porch.

“I’m Sheriff Harley Shepherd,” he said. “I was just driving by. Been some years since I been out in this neck of the woods. You are new here, aren’t you?”

The man rose to his feet and gestured at another chair. “Been here three years or so,” he said. “The name is Wallace Daniels. Come up and sit with me.”

The sheriff climbed the stairs and the two shook hands, then sat down in the chairs.

“You don’t farm the place,” the sheriff said.

The weed-grown fields came up to the fence that hemmed in the yard.

Daniels shook his head. “Subsistence farming, if you can call it that. A few chickens for eggs. A couple of cows for milk and butter. Some hogs for meat—the neighbors help me butcher. A garden of course, but that’s about the story.”

“Just as well,” the sheriff said. “The place is all played out. Old Amos Williams, he let it go to ruin. He never was no farmer.”

“The land is resting now,” said Daniels. “Give it ten years—twenty might be better—and it will be ready once again. The only things it’s good for now are the rabbits and the woodchucks and the meadow mice. A lot of birds, of course. I’ve got the finest covey of quail a man has ever seen.”

“Used to be good squirrel country,” said the sheriff. “Coon, too. I suppose you still have coon. You have a hunter, Mr. Daniels?”

“I don’t own a gun,” said Daniels.

The sheriff settled deeply into the chair, rocking gently.

“Pretty country out here,” he declared. “Especially with the leaves turning colors. A lot of hardwood and they are colorful. Rough as hell, of course, this land of yours. Straight up and down, the most of it. But pretty.”

“It’s old country,” Daniels said. “The last sea retreated from this area more than four hundred million years ago. It has stood as dry land since the end of the Silurian. Unless you go up north, on to the Canadian Shield, there aren’t many places in this country you can find as old as this.”

“You a geologist, Mr. Daniels?”

“Not really. Interested, is all. The rankest amateur. I need something to fill my time and I do a lot of hiking, scrambling up and down these hills. And you can’t do that without coming face to face with a lot of geology. I got interested. Found some fossil brachiopods and got to wondering about them. Sent off for some books and read up on them. One thing led to another and—”

“Brachiopods? Would they be dinosaurs, or what? I never knew there were dinosaurs out this way.”

“Not dinosaurs,” said Daniels. “Earlier than dinosaurs, at least the ones I found. They’re small. Something like clams or oysters. But the shells are hinged in a different sort of way. These were old ones, extinct millions of years ago. But we still have a few brachiopods living now. Not too many of them.”

“It must be interesting.”

“I find it so,” said Daniels.

“You knew old Amos Williams?”

“No. He was dead before I came here. Bought the land from the bank that was settling his estate.”

“Queer old coot,” the sheriff said. “Fought with all his neighbors. Especially with Ben Adams. Him and Ben had a line fence feud going on for years. Ben said Amos refused to keep up the fence. Amos claimed Ben knocked it down and then sort of, careless-like, hazed his cattle over into Amos’s hayfield. How you get along with Ben?”

“All right,” Daniels said. “No trouble. I scarcely know the man.”

“Ben don’t do much farming, either,” said the sheriff. Hunts and fishes, hunts ginseng, does some trapping in the winter. Prospects for minerals now and then.”

“There are minerals in these hills,” said Daniels. “Lead and zinc. But it would cost more to get it out than it would be worth. At present prices, that is.”

“Ben always has some scheme cooking.” said the sheriff. “Always off on some wild goose chase. And he’s a pure pugnacious man. Always has his nose out of joint about something. Always on the prod for trouble. Bad man to have for an enemy. Was in the other day to say someone’s been lifting a hen or two of his. You haven’t been missing any, have you?”

Daniels grinned. “There’s a fox that levies a sort of tribute on the coop every now and then. I don’t begrudge them to him.”

“Funny thing,” the sheriff said. “There ain’t nothing can rile up a farmer like a little chicken stealing. It don’t amount to shucks, of course, but they get real hostile at it.”

“If Ben has been losing chickens,” Daniels said, “more than likely the culprit is my fox.”

“Your fox? You talk as if you own him.”

“Of course I don’t. No one owns a fox. But he lives in these hills with me. I figure we are neighbours. I see him every now and then and watch him. Maybe that means I own a piece of him. Although I wouldn’t be surprised if he watches me more than I watch him. He moves quicker than I do.”

The sheriff heaved himself out of the chair.

“I hate to go,” he said. “I declare it has been restful sitting here and talking with you and looking at the hills. You look at them a lot, I take it.”

“Quite a lot,” said Daniels.

He sat on the porch and watched the sheriff’s car top the rise far down the ridge and disappear from sight.

What had it all been about? he wondered. The sheriff hadn’t just happened to be passing by. He’d been on an errand. All this aimless, friendly talk had not been for nothing and in the course of it he’d managed to ask lots of questions.

Something about Ben Adams, maybe? Except there wasn’t too much against Adams except he was bone-lazy. Lazy in a weasely sort of way. Maybe the sheriff had got wind of Adams’ off-and-on moonshining operation and was out to do some checking, hoping that some neighbor might misspeak himself. None of them would, of course, for it was none of their business, really, and the moonshining had built up no nuisance value. What little liquor Ben might make didn’t amount to much. He was too lazy for anything he did to amount to much.

From far down the hill he heard the tinkle of a bell. The two cows were finally heading home. It must be much later, Daniels told himself, than he had thought. Not that he paid much attention to what time it was. He hadn’t for long months on end, ever since he’d smashed his watch when he’d fallen off the ledge. He had never bothered to have the watch fixed. He didn’t need a watch. There was a battered old alarm clock in the kitchen but it was an erratic piece of mechanism and not to be relied upon. He paid slight attention to it.

In a little while, he thought, he’d have to rouse himself and go and do the chores—milk the cows, feed the hogs and chickens, gather up the eggs. Since the garden had been laid by there hadn’t been much to do. One of these days he’d have to bring in the squashes and store them in the cellar and there were those three or four big pumpkins he’d have to lug down the hollow to the Perkins kids, so they’d have them in time to make jack-o-lanterns for Halloween. He wondered if he should carve out the faces himself or if the kids would rather do it on their own.

But the cows were still quite a distance away and he still had time. He sat easy in his chair and stared across the hills.

And they began to shift and change as he stared.

When he had first seen it, the phenomenon had scared him silly. But now he was used to it.

As he watched, the hills changed into different ones. Different vegetation and strange life stirred on them.

He saw dinosaurs this time. A herd of them, not very big ones. Middle Triassic, more than likely. And this time it was only a distant view—he himself was not to become involved. He would only see, from a distance, what ancient time was like and would not be thrust into the middle of it as most often was the case.

He was glad. There were chores to do.

Watching, he wondered once again what more he could do. It was not the dinosaurs that concerned him, nor the earlier amphibians, nor all the other creatures that moved in time about the hills.

What disturbed him was that other being that lay buried deep beneath the Platteville limestone.

Someone else should know about it. The knowledge of it should be kept alive so that in the days to come—perhaps in another hundred years—when man’s technology had reached the point where it was possible to cope with such a problem, something could be done to contact—and perhaps to free—the dweller in the stone.

There would be a record, of course, a written record. He would see to that. Already that record was in progress—a week by week (at times a day to day) account of what he had seen, heard and learned. Three large record books now were filled with his careful writing and another one was well started. All written down as honestly and as carefully and as objectively as he could bring himself to do it.

But who would believe what he had written? More to the point, who would bother to look at it? More than likely the books would gather dust on some hidden shelf until the end of time with no human hand ever laid upon them. And even if someone, in some future time, should take them down and read them, first blowing away the accumulated dust, would he or she be likely to believe?

The answer lay clear. He must convince someone. Words written by a man long dead—and by a man of no reputation—could be easily dismissed as the product of a neurotic mind. But if some scientist of solid reputation could be made to listen, could be made to endorse the record, the events that paraded across the hills and lay within them could stand on solid ground, worthy of full investigation at some future date.

A biologist? Or a neuropsychiatrist? Or a paleontologist?

Perhaps it didn’t matter what branch of science the man was in. Just so he’d listen without laughter. It was most important that he listen without laughter.

Sitting on the porch, staring at the hills dotted with grazing dinosaurs, the listener to the stars remembered the time he had gone to see the paleontologist.

“Ben,” the sheriff said. “you’re way out in left field. That Daniels fellow wouldn’t steal no chickens. He’s got chickens of his own.”

“The question is,” said Adams, “how did he get them chickens?”

“That makes no sense,” the sheriff said. “He’s a gentleman. You can tell that just by talking with him. An educated gentleman.”

“If he’s a gentleman,” asked Adams, “what’s he doing out here? This ain’t no place for gentlemen. He showed up two or three years ago and moved out to this place. Since that day he hasn’t done a tap of work. All he does is wander up and down the hills.”

“He’s a geologist,” said the sheriff. “Or anyway interested in geology. A sort of hobby with him. He tells me he looks for fossils.”

Adams assumed the alert look of a dog that has sighted a rabbit. “So that is it,” he said. “I bet you it ain’t fossils he is looking for.”

“No,” the sheriff said.

“He’s looking for minerals,” said Adams. “He’s prospecting, that’s what he’s doing. These hills crawl with minerals. All you have to do is know where to look.”

“You’ve spent a lot of time looking,” observed the sheriff. “I ain’t no geologist. A geologist would have a big advantage. He would know rocks and such.”

“He didn’t talk as if he were doing any prospecting. Just interested in the geology, is all. He found some fossil clams.”

“He might be looking for treasure caves,” said Adams. “He might have a map or something.”

“You know damn well,” the sheriff said, “there are no treasure caves.”

“There must be,” Adams insisted. “The French and Spanish were here in the early days. They were great ones for treasure, the French and Spanish. Always running after mines. Always hiding things in caves. There was that cave over across the river where they found a skeleton in Spanish armour and the skeleton of a bear beside him, with a rusty sword stuck into where the bear’s gizzard was.”

“That was just a story,” said the sheriff, disgusted. “Some damn fool started it and there was nothing to it. Some people from the university came out and tried to run it down. It developed that there wasn’t a word of truth in it.”

“But Daniels has been messing around with caves,” said Adams. “I’ve seen him. He spends a lot of time in that cave down on Cat Den Point. Got to climb a tree to get to it.”

“You been watching him?”

“Sure I been watching him. He’s up to something and I want to know what it is.”

“Just be sure he doesn’t catch you doing it,” the sheriff said.

Adams chose to let the matter pass. “Well, anyhow,” he said, “if there aren’t any treasure caves, there’s a lot of lead and zinc. The man who finds it is about to make a million.”

“Not unless he can find the capital to back him,” the sheriff pointed out.

Adams dug at the ground with his heel. “You think he’s all right, do you?”

“He tells me he’s been losing some chickens to a fox. More than likely that’s what has been happening to yours.”

“If a fox is taking his chickens,” Adams asked, “why don’t he shoot it?”

“He isn’t sore about it. He seems to think the fox has got a right to. He hasn’t even got a gun.”

“Well, if he hasn’t got a gun and doesn’t care to hunt himself—then why won’t he let other people hunt? He won’t let me and my boys on his place with a gun. He has his place all posted. That seems to me to be un-neighborly. That’s one of the things that makes it so hard to get along with him. We’ve always hunted on that place. Old Amos wasn’t an easy man to get along with but he never cared if we did some hunting. We’ve always hunted all around here. No one ever minded. Seems to me hunting should be free. Seems right for a man to hunt wherever he’s a mind to.”

Sitting on the bench on the hard-packed earth in front of the ramshackle house, the sheriff looked about him—at the listlessly scratching chickens, at the scrawny hound sleeping in the shade, its hide twitching against the few remaining flies, at the clothes-line strung between two trees and loaded with drying clothes and dish towels, at the washtub balanced on its edge on a wash bench leaning against the side of the house.

Christ, he thought, the man should be able to find the time to put up a decent clothes-line and not just string a rope between two trees.

“Ben,” he said, “you’re just trying to stir up trouble. You resent Daniels, a man living on a farm who doesn’t work at farming, and you’re sore because he won’t let you hunt his land. He’s got a right to live anywhere he wants to and he’s got a right not to let you hunt. I’d lay off him if I were you. You don’t have to like him, you don’t have to have anything to do with him—but don’t go around spreading fake accusations against the man. He could jerk you up in court for that.”

2

He had walked into the paleontologist’s office and it had taken him a moment fully to see the man seated toward the back of the room at a cluttered desk. The entire place was cluttered. There were long tables covered with chunks of rock with embedded fossils, Scattered here and there were stacks of papers. The room was large and badly lighted. It was a dingy and depressing place.

“Doctor?” Daniels had asked. “Are you Dr. Thorne?”

The man rose and deposited a pipe in a cluttered ashtray. He was big, burly, with graying hair that had a wild look to it. His face was seamed and weather-beaten. When he moved he shuffled like a bear.

“You must be Daniels,” he said. “Yes, I see you must be. I had you on my calendar for three o’clock. So glad you could come.”

His great paw engulfed Daniel’s hand. He pointed to a chair beside the desk, sat down and retrieved his pipe from the overflowing tray, began packing it from a large canister that stood on the desk.

“Your letter said you wanted to see me about something important,” he said. “But then that’s what they all say. But there must have been something about your letter—an urgency, a sincerity. I haven’t the time, you understand, to see everyone who writes. All of them have found something, you see. What is it, Mr. Daniels, that you have found?”

Daniels said, “Doctor, I don’t quite know how to start what I have to say. Perhaps it would be best to tell you first that something had happened to my brain.”

Thorne was lighting his pipe. He talked around the stem. “In such a case, perhaps I am not the man you should be talking to. There are other people—”

“No, that’s not what I mean,” said Daniels. “I’m not seeking help. I am quite all right physically and mentally, too. About five years ago I was in a highway accident. My wife and daughter were killed and I was badly hurt and—”

“I am sorry, Mr. Daniels.”

“Thank you—but that is all in the past. It was rough for a time but I muddled through it. That’s not what I’m here for. I told you I was badly hurt—”

“Brain damage?”

“Only minor. Or so far as the medical findings are concerned. Very minor damage that seemed to clear up rather soon. The bad part was the crushed chest and punctured lung.”

“But you’re all right now?”

“As good as new,” said Daniels. “But since the accident my brain’s been different. As if I had new senses. I see things, understand things that seem impossible.”

“You mean you have hallucinations?”

“Not hallucinations. I am sure of that. I can see the past.”

“How do you mean—see the past?”

“Let me try to tell you,” Daniels said. “exactly how it started. Several years ago I bought an abandoned farm in south-western Wisconsin. A place to hole up in, a place to hide away. With my wife and daughter gone I still was recoiling from the world. I had got through the first brutal shock but I needed a place where I could lick my wounds. If this sounds like self-pity—I don’t mean it that way. I am trying to be objective about why I acted as I did, why I bought the farm.”

“Yes. I understand,” said Thorne. “But I’m not entirely sure hiding was the wisest thing to do.”

“Perhaps not, but it seemed to me the answer. It has worked out rather well. I fell in love with the country. That part of Wisconsin is ancient land. It has stood uncovered by the sea for four hundred million years. For some reason it was not overridden by the Pleistocene glaciers. It has changed, of course, but only as the result of weathering. There have been no great geologic upheavals, no massive erosions—nothing to disturb it.”

“Mr. Daniels,” said Thorne, somewhat testily, “I don’t quite see what this has to do—”

“I’m sorry. I am just trying to lay the background for what I came to tell you. It came on rather slowly at first and I thought that I was crazy, that I was seeing things, that there had been more brain damage than had been apparent—or that I was finally cracking up. I did a lot of walking in the hills, you see. The country is wild and rugged and beautiful—a good place to be out in. The walking made me tired and I could sleep at night. But at times the hills changed. Only a little at first. Later on they changed more and finally they became places I had never seen before, that no one had ever seen before.”

Thorne scowled. “You are trying to tell me they changed into the past.”

Daniels nodded. “Strange vegetation, funny-looking trees. In the earlier times, of course, no grass at all. Underbrush of ferns and scouring rushes. Strange animals, strange things in the sky. Saber-tooth cats and mastodons, pterosaurs and uintatheres and—”

“All at the same time?” Thorne asked, interrupting. “All mixed up?”

“Not at all. The time periods I see seem to be true time periods. Nothing out of place. I didn’t know at first—but when I was able to convince myself that I was not hallucinating I sent away for books. I studied. I’ll never be an expert, of course—never a geologist or paleontologist—but I learned enough to distinguish one period from another, to have some idea of what I was looking at.”

Thorne took his pipe out of his mouth and perched it in the ashtray. He ran a massive hand through his wild hair.

“It’s unbelievable,” he said. “It simply couldn’t happen. You said all this business came on rather slowly?”

“To begin with it was hazy, the past foggily imposed upon the present, then the present would slowly fade and the past came in, real and solid. But it’s different now. Once in a while there’s a bit of flickering as the present gives way to the past—but mostly it simply changes, as if at the snap of a finger. The present goes away and I’m standing in the past. The past is all around me. Nothing of the present is left.”

“But you aren’t really in the past? Physically, I mean.”

“There are times when I’m not in it at all. I stand in the present and the distant hills or the river valley changes. But ordinarily it changes all around me, although the funny thing about it is that, as you say, I’m not really in it. I can see it and it seems real enough for me to walk around in it. I can walk over to a tree and put my hand out to feel it and the tree is there, But I seem to make no impact on the past. It’s as if I were not there at all. The animals do not see me. I’ve walked up to within a few feet of dinosaurs. They can’t see me or hear or smell me. If they had I’d have been dead a dozen times. It’s as if I were walking through a three-dimensional movie. At first I worried a lot about the surface differences that might exist. I’d wake up dreaming of going into the past and being buried up to my waist in a rise of ground that since has eroded away. But it doesn’t work that way. I’m walking along in the present and then I’m walking in the past. It’s as if a door were there and I stepped through it. I told you I don’t really seem to be in the past—but I’m not in the present, either. I tried to get some proof. I took a camera with me and shot a lot of pictures. When the films were developed there was nothing on them. Not the past—but what is more important, not the present, either. If I had been hallucinating, the camera should have caught pictures of the present. But apparently there was nothing there for the camera to take. I thought maybe the camera failed or I had the wrong kind of film. So I tried several cameras and different types of film and nothing happened. I got no pictures. I tried bringing something back. I picked flowers, after there were flowers. I had no trouble picking them but when I came back to the present I was empty-handed. I tried to bring back other things as well. I thought maybe it was only live things, like flowers, that I couldn’t bring, so I tried inorganic things—like rocks—but I never was able to bring anything back.”

“How about a sketch pad?”

“I thought of that but I never used one. I’m no good at sketching—besides, I figured, what was the use? The pad would come back blank.”

“But you never tried.”

“No,” said Daniels. “I never tried. Occasionally I do make sketches after I get back to the present. Not every time but sometimes. From memory. But, as I said, I’m not very good at sketching.”

“I don’t know,” said Thorne. “I don’t really know. This all sounds incredible. But if there should be something to it—Tell me, were you ever frightened? You seem quite calm and matter-of-fact about it now, but at first you must have been frightened.”

“At first,” said Daniels, “I was petrified. Not only was I scared, physically scared—frightened for my safety, frightened that I’d fallen into a place from which I never could escape—but also afraid that I’d gone insane. And there was the loneliness.”

“What do you mean—loneliness?”

“Maybe that’s not the right word. Out of place. I was where I had no right to be. Lost in a place where man had not as yet appeared and would not appear for millions of years. In a world so utterly alien that I wanted to hunker down and shiver. But I, not the place, was really the alien there. I still get some of that feeling every now and then. I know about it, of course, and am braced against it, but at times it still gets to me. I’m a stranger to the air and the light of that other time—it’s all imagination, of course.”

“Not necessarily,” said Thorne.

“But the greatest fear is gone now, entirely gone. The fear I was insane. I am convinced now.”

“How are you convinced? How could a man be convinced?”

“The animals. The creatures I see—”

“You mean you recognize them from the illustrations in these books you have been reading.”

“No, not that. Not entirely that. Of course the pictures helped. But actually it’s the other way around. Not the likeness, but the differences. You see, none of the creatures are exactly like the pictures in the books. Some of them not at all like them. Not like the reconstruction the paleontologists put together. If they had been I might still have thought they were hallucinations, that what I was seeing was influenced by what I’d seen or read. I could have been feeding my imagination on prior knowledge. But since that was not the case, it seemed logical to assume that what I see is real. How could I imagine that Tyrannosaurus had dewlaps all the colors of the rainbow? How could I imagine that some of the saber-tooths had tassels on their ears? How could anyone possibly imagine that the big thunder beasts of the Eocene had hides as colorful as giraffes?”

“Mr. Daniels,” said Thorne, “I have great reservations about all that you have told me, Every fiber of my training rebels against it. I have a feeling that I should waste no time on it. Undoubtedly, you believe what you have told me. You have the look of an honest man about you. Have you talked to any other men about this? Any other paleontologists or geologists? Perhaps a neuropsychiatrist?”

“No,” said Daniels. “You’re the only person, the only man I have talked with. And I haven’t told you all of it. This is really all just background.”

“My God, man—just background?”

“Yes, just background. You see, I also listen to the stars.” Thorne got up from his chair, began shuffling together a stack of papers. He retrieved the dead pipe from the ashtray and stuck it in his mouth.

His voice, when he spoke, was noncommittal.

“Thank you for coming in,” he said. “It’s been most interesting.”