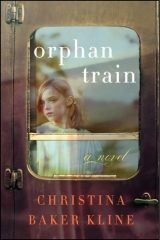

Текст книги "Orphan Train"

Автор книги: Christina Baker Kline

Жанры:

Историческое фэнтези

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 4 (всего у книги 19 страниц)

Spruce Harbor, Maine, 2011

Walking back to the car, Molly sees Jack through the windshield, eyes closed, grooving out to a song she can’t hear.

“Hey,” she says loudly, opening the passenger door.

He opens his eyes and yanks the buds out of his ears. “How’d it go?”

She shakes her head and climbs in. Hard to believe she was only in there for twenty minutes. “Vivian’s an odd one. Fifty hours! My God.”

“But it’s going to work out?”

“I guess so. We made a plan to start on Monday.”

Jack pats her leg. “Awesome. You’ll knock out those hours in no time.”

“Let’s not count our chickens.”

She’s always doing this, crabbily countering his enthusiasm, but it’s become something of a routine. She’ll tell him, “I’m nothing like you, Jack. I’m bitchy and spiteful,” but is secretly relieved when he laughs it off. He has an optimistic certainty that she’s a good person at her core. And if he has this faith in her, then she must be all right, right?

“Just keep telling yourself—better than juvie,” he says.

“Are you sure about that? It’d probably be easier to serve my time and get it over with.”

“Except for that small problem of having a record.”

She shrugs. “That’d be kind of badass, though, don’t you think?”

“Really, Moll?” he says with a sigh, turning the ignition key.

She smiles to let him know she’s kidding. Sort of. “‘Better than juvie.’ That would make a good tattoo.” She points to her arm. “Right here across my bicep, in twenty-point script.”

“Don’t even joke,” he says.

DINA PLUNKS THE SKILLET OF HAMBURGER HELPER ON THE TRIVET in the middle of the table and sits heavily in her chair. “Oof. I’m exhausted.”

“Tough day at work, huh, babe?” Ralph says, as he always does, though Dina never asks him about his day. Maybe plumbing isn’t as exciting as being a police dispatcher in thrill-a-minute Spruce Harbor. “Molly, hand me your plate.”

“My back is killing me from that crappy chair they make me sit in,” Dina says. “I swear if I went to a chiropractor, I’d have a lawsuit.”

Molly gives her plate to Ralph and he drops some casserole on it. Molly has learned to pick around the meat—even in a dish like this, where you can hardly tell what’s what and it’s all mixed together—because Dina refuses to acknowledge that she’s a vegetarian.

Dina listens to conservative talk radio, belongs to a fundamentalist Christian church, and has a “Guns don’t kill people—abortion clinics do” bumper sticker on her car. She and Molly are about as opposite as it is possible to be, which would be fine if Dina didn’t take Molly’s choices as a personal affront. Dina is constantly rolling her eyes, muttering under her breath about Molly’s various infractions—didn’t put away her laundry, left a bowl in the sink, can’t be bothered to make her bed—all of which are part and parcel of the liberal agenda that’s ruining this country. Molly knows she should ignore these comments—“water off a duck’s back,” Ralph says—but they irk her. She’s overly sensitive to them, like a tuning fork pitched too high. It’s all part of Dina’s unwavering message: Be grateful. Dress like a normal person. Don’t have opinions. Eat the food that’s put in front of you.

Molly can’t quite figure out how Ralph fits into all of this. She knows he and Dina met in high school, followed a predictable football player/ cheerleader story arc, and have been together ever since, but she can’t tell if Ralph actually buys Dina’s party line or just toes it to make his life easier. Sometimes she sees a glimmer of independence—a raised eyebrow, a carefully worded, possibly ironic observation, like, “Well, we can’t make a decision on that till the boss gets home.”

Still—all things considered, Molly knows she has it pretty good: her own room in a tidy house, employed and sober foster parents, a decent high school, a nice boyfriend. She isn’t expected to take care of a passel of kids, as she was at one of the places she lived, or clean up after fifteen dirty cats, as she was at another. In the past nine years she’s been in over a dozen foster homes, some for as little as a week. She’s been spanked with a spatula, slapped across the face, made to sleep on an unheated sun porch in the winter, taught to roll a joint by a foster father, fed lies for the social worker. She got her tatt illegally at sixteen from a twenty-three-year-old friend of the Bangor family, an “ink expert-in-training,” as he called himself, who was just starting out and did it for free—or, well . . . sort of. She wasn’t so attached to her virginity anyway.

With the tines of her fork, Molly mashes the hamburger into her plate, hoping to grind it into oblivion. She takes a bite and smiles at Dina. “Good. Thanks.”

Dina purses her lips and cocks her head, clearly trying to gauge whether Molly’s praise is sincere. Well, Dina, Molly thinks, it is and it isn’t. Thank you for taking me in and feeding me. But if you think you can quash my ideals, force me to eat meat when I told you I don’t, expect me to care about your aching back when you don’t seem the slightest bit interested in my life, you can forget it. I’ll play your fucking game. But I don’t have to play by your rules.

Spruce Harbor, Maine, 2011

Terry leads the way to the third floor, bustling up the stairs, with Vivian moving more slowly behind her and Molly taking up the rear. The house is large and drafty—much too large, Molly thinks, for an old woman who lives alone. It has fourteen rooms, most of which are shuttered during the winter months. During the Terry-narrated tour on the way to the attic, Molly gets the story: Vivian and her husband owned and ran a department store in Minnesota, and when they sold it twenty years ago, they took a sailing trip up the East Coast to celebrate their retirement. They spied this house, a former ship captain’s estate, from the harbor, and on an impulse decided to buy it. And that was it: they packed up and moved to Maine. Ever since Jim died, eight years ago, Vivian has lived here by herself.

In a clearing at the top of the stairs, Terry, panting a bit, puts her hand on her hip and looks around. “Yikes! Where to start, Vivi?”

Vivian reaches the top step, clutching the banister. She is wearing another cashmere sweater, gray this time, and a silver necklace with an odd little charm on it.

“Well, let’s see.”

Glancing around, Molly can see that the third floor of the house consists of a finished section—two bedrooms tucked under the slope of the roof and an old-fashioned bathroom with a claw-foot tub—and a large, open attic part with a rough-planked floor half covered in patches of ancient linoleum. It has visible rafters with insulation packed between the beams. Though the rafters and floor are dark, the space is surprisingly light. Levered windows nestle in each dormer, providing a clear view of the bay and the marina beyond.

The attic is filled with boxes and furniture packed so tightly it’s hard to move around. In one corner is a long clothes rack covered with a plastic zippered case. Several cedar chests, so large that Molly wonders how they got up here in the first place, are lined up against a wall next to a stack of steamer trunks. Overhead, several bare bulbs glow like tiny moons.

Wandering among the cardboard boxes, Vivian trails her fingertips across the tops of them, peering at their cryptic labels: The store, 1960–. The Nielsens. Valuables. “I suppose this is why people have children, isn’t it?” she muses. “So somebody will care about the stuff they leave behind.”

Molly looks over at Terry, who is shaking her head with grim resignation. It occurs to her that maybe Terry’s reluctance to take on this project has as much to do with avoiding this kind of maudlin moment as avoiding the work itself.

Glancing surreptitiously at her phone, Molly sees it’s 4:15—only fifteen minutes since she arrived. She’s supposed to stay until six today, and then come for two hours four days a week, and four hours every weekend until—well, until she finishes her time or Vivian drops dead, whichever comes first. According to her calculations, it should take about a month. To finish the hours, not to kill Vivian.

Though if the next forty-nine hours and forty-five minutes are this tedious, she doesn’t know if she’ll be able to stand it.

In American History they’ve been studying how the United States was founded on indentured servitude. The teacher, Mr. Reed, said that in the seventeenth century nearly two-thirds of English settlers came over that way, selling years of their freedom for the promise of an eventual better life. Most of them were under the age of twenty-one.

Molly has decided to think of this job as indentured servitude: each hour she works is another hour closer to freedom.

“It’ll be good to clear out this stuff, Vivi,” Terry is saying. “Well, I’m going to get started on the laundry. Call if you need me!” She nods to Molly as if to say All yours! and retreats down the stairs.

Molly knows all about Terry’s work routine. “You’re like me at the gym, hey, Ma?” Jack says, teasing her about it. “One day biceps, next day quads.” Terry rarely deviates from her self-imposed schedule; with a house this size, she says, you have to tackle a different section every day: bedrooms and laundry on Monday, bathrooms and plants on Tuesday, kitchen and shopping on Wednesday, other main rooms on Thursday, cooking for the weekend on Friday.

Molly wades through stacks of boxes sealed with shiny beige tape to get to the window, which she opens a crack. Even up here, at the top of this big old house, she can smell the salty air. “They’re not in any particular order, are they?” she asks Vivian, turning back around. “How long have they been here?”

“I haven’t touched them since we moved in. So that must be—”

“Twenty years.”

Vivian gives her a flinty smile. “You were listening.”

“Were you ever tempted to just toss it all in a Dumpster?”

Vivian purses her lips.

“I didn’t mean—sorry.” Molly winces, realizing she’s pushed a little far.

All right, it’s official, she needs an attitude adjustment. Why is she so hostile? Vivian hasn’t done anything to her. She should be grateful. Without Vivian she’d be sliding down a dark path toward nowhere good. But it kind of feels nice to nurture her resentment, to foster it. It’s something she can savor and control, this feeling of having been wronged by the world. That she has fulfilled her role as a thieving member of the underclass, now indentured to this genteel midwestern white lady, is too perfect for words.

Deep breath. Smile. As Lori, the court-ordered social worker she meets with biweekly always tells her to do, Molly decides to make a mental list of all the positive things about her situation. Let’s see. One, if she can stick it out, this whole incident will be stricken from her record. Two, she has a place—however tense and tenuous at the moment—to live. Three, if you must spend fifty hours in an uninsulated attic in Maine, spring is probably the best time of year to do it. Four, Vivian is ancient, but she doesn’t appear to be senile.

Five—who knows? Maybe there actually will be something interesting in these boxes.

Bending down, Molly scans the labels around her. “I think we should go through them in chronological order. Let’s see—this one says ‘WWII.’ Is there anything before that?”

“Yes.” Vivian squeezes between two stacks and makes her way toward the cedar chests. “The earliest stuff I have is over here, I think. These crates are too heavy to move, though. So we’ll have to start in this corner. Is that okay with you?”

Molly nods. Downstairs, Terry handed her a cheap serrated knife with a plastic handle, a slippery stack of white plastic garbage bags, and a wire-bound notebook with a pen clipped to it to keep track of “inventory,” as she called it. Now Molly takes the knife and pokes it through the tape of the box Vivian has chosen: 1929–1930. Vivian, sitting on a wooden chest, waits patiently. After opening the flaps, Molly lifts out a mustard-colored coat, and Vivian scowls. “Mercy sake,” she says. “I can’t believe I saved that coat. I always hated it.”

Molly holds the coat up, inspecting it. It’s interesting, actually, sort of a military style with bold black buttons. The gray silk lining is disintegrating. Going through the pockets, she fishes out a folded piece of lined paper, almost worn away at the creases. She unfolds it to reveal a child’s careful cursive in faint pencil, practicing the same sentence over and over again: Upright and do right make all right. Upright and do right make all right. Upright and do right . . .

Vivian takes it from her and spreads the paper open on her knee. “I remember this. Miss Larsen had the most beautiful penmanship.”

“Your teacher?”

Vivian nods. “Try as I might, I could never form my letters like hers.”

Molly looks at the perfect swoops hitting the broken line in exactly the same spot. “Looks pretty good to me. You should see my scrawl.”

“They barely teach it anymore, I hear.”

“Yeah, everything’s on computer.” Molly is suddenly struck by the fact that Vivian wrote these words on this sheet of paper more than eighty years ago. Upright and do right make all right. “Things have changed a lot since you were my age, huh?”

Vivian cocks her head. “I suppose. Most of it doesn’t affect me much. I still sleep in a bed. Sit in a chair. Wash dishes in a sink.”

Or Terry washes dishes in a sink, to be accurate, Molly thinks.

“I don’t watch much television. You know I don’t have a computer. In a lot of ways my life is just as it was twenty or even forty years ago.”

“That’s kind of sad,” Molly blurts, then immediately regrets it. But Vivian doesn’t seem offended. Making a “who cares?” face, she says, “I don’t think I’ve missed much.”

“Wireless Internet, digital photographs, smartphones, Facebook, YouTube . . .” Molly taps the fingers of one hand. “The entire world has changed in the past decade.”

“Not my world.”

“But you’re missing out on so much.”

Vivian laughs. “I hardly think FaceTube—whatever that is—would improve my quality of life.”

Molly shakes her head. “It’s Facebook. And YouTube.”

“Whatever!” Vivian says breezily. “I don’t care. I like my quiet life.”

“But there’s a balance. Honestly, I don’t know how you can just exist in this—bubble.”

Vivian smiles. “You don’t have trouble speaking your mind, do you?”

So she’s been told. “Why did you keep this coat, if you hated it?” Molly asks, changing the subject.

Vivian picks it up and holds it out in front of her. “That’s a very good question.”

“So should we put it in the Goodwill pile?”

Folding the coat in her lap, Vivian says, “Ah . . . maybe. Let’s see what else is in this box.”

The Milwaukee Train, 1929

I sleep badly the last night on the train. Carmine is up several times in the night, irritable and fidgety, and though I try to soothe him, he cries fitfully for a long time, disturbing the children around us. As dawn emerges in streaks of yellow, he finally falls asleep, his head on Dutchy’s curled leg and his feet in my lap. I am wide-awake, so filled with nervous energy that I can feel the blood pumping through my heart.

I’ve been wearing my hair pulled back in a messy ponytail, but now I untie the old ribbon and let it fall to my shoulders, combing through it with my fingers and smoothing the tendrils around my face. I pull it back as tightly as I can.

Turning, I catch Dutchy looking at me.

“Your hair is pretty.” I squint at him in the gloom to see if he’s teasing, and he looks back at me sleepily.

“That’s not what you said a few days ago.”

“I said you’ll have a hard time.”

I want to push away both his kindness and his honesty.

“Can’t help what you are, can you,” he says.

I crane my neck to see if Mrs. Scatcherd might have heard us, but there’s no movement up front.

“Let’s make a promise,” he says. “To find each other.”

“How can we? We’ll probably end up in different places.”

“I know.”

“And my name will be changed.”

“Mine too, maybe. But we can try.”

Carmine flops over, tucking his legs beneath him and stretching his arms, and both of us shift to accommodate him.

“Do you believe in fate?” I ask.

“What’s that again?”

“That everything is decided. You’re just—you know—living it out.”

“God has it all planned in advance.”

I nod.

“I dunno. I don’t like the plan much so far.”

“Me either.”

We both laugh.

“Mrs. Scatcherd says we should make a clean slate,” I say. “Let go of the past.”

“I can let go of the past, no problem.” He picks up the wool blanket that has fallen to the floor and tucks it around the lump of Carmine’s body, covering the parts that are exposed. “But I don’t want to forget everything.”

OUTSIDE THE WINDOW I SEE THREE SETS OF TRACKS PARALLELING the one we are on, brown and silver, and beyond them broad flat fields of furrowed soil. The sky is clear and blue. The train car smells of diaper rags and sweat and sour milk.

At the front of the car Mrs. Scatcherd stands up, bends down to confer with Mr. Curran, and stands up again. She is wearing her black bonnet.

“All right, children. Wake up!” she says, looking around, clapping her hands several times. Her eyeglasses glint in the morning light.

Around me I hear small grunts and sighs as those lucky enough to have slept stretch out their cramped limbs.

“It is time to make yourselves presentable. Each of you has a change of clothing in your suitcase, which as you know is on the rack overhead. Big ones, please assist the little ones. I cannot stress enough how important it is to make a good first impression. Clean faces, combed hair, shirts tucked in. Bright eyes and smiles. You will not fidget or touch your face. And you will say what, Rebecca?”

We’re familiar with the script: “Please and thank you,” Rebecca says, her voice barely audible.

“Please and thank you what?”

“Please and thank you, ma’am.”

“You will wait to speak until you are spoken to, and then you will say please and thank you, ma’am. You will wait to do what, Andrew?”

“Speak until you are spoken to?”

“Exactly. You will not fidget or what, Norma?”

“Touch your face. Ma’am. Ma’am madam.”

Titters erupt from the seats. Mrs. Scatcherd glares at us. “This amuses you, does it? I don’t imagine you’ll think it’s quite so funny when all the adults say no thank you, I do not want a rude, slovenly child, and you’ll have to get back on the train and go to the next station. Do you think so, Mr. Curran?”

Mr. Curran’s head jerks up at the sound of his name. “No indeed, Mrs. Scatcherd.”

The train is silent. Not getting chosen isn’t something we want to think about. A little girl in the row behind me begins to cry, and soon I can hear muffled sniffs all around me. At the front of the train, Mrs. Scatcherd clasps her hands together and curls her lips into something resembling a smile. “Now, now. No need for that. As with almost everything in life, if you are polite and present yourself favorably, it is probable that you will succeed. The good citizens of Minneapolis are coming to the meeting hall today with the earnest intention of taking one of you home—possibly more than one. So remember, girls, tie your hair ribbons neatly. Boys, clean faces and combed hair. Shirts buttoned properly. When we disembark, you will stand in a straight line. You will speak only when spoken to. In short, you will do everything in your power to make it easy for an adult to choose you. Is that clear?”

The sun is so bright that I have to squint, so hot that I edge to the middle seat, out of the glare of the window, scooping Carmine onto my lap. As we go under bridges and pull through stations the light flickers and Carmine makes a shadow game of moving his hand across my white pinafore.

“You should make out all right,” Dutchy says in a low voice. “At least you won’t be breaking your back doing farm work.”

“You don’t know that I won’t,” I say. “And you don’t know that you will.”

Milwaukee Road Depot, Minneapolis, 1929

The train pulls into the station with a high-pitched squealing of brakes and a great gust of steam. Carmine is quiet, gaping at the buildings and wires and people outside the window, after hundreds of miles of fields and trees.

We stand and begin to gather our belongings. Dutchy reaches up for our bags and sets them in the aisle. Out the window I can see Mrs. Scatcherd and Mr. Curran on the platform talking to two men in suits and ties and black fedoras, with several policemen behind them. Mr. Curran shakes their hands, then sweeps his hand toward us as we step off the train.

I want to say something to Dutchy, but I can’t think of what. My hands are clammy. It’s a terrible kind of anticipation, not knowing what we’re walking into. The last time I felt this way I was in the waiting rooms at Ellis Island. We were tired, and Mam wasn’t well, and we didn’t know where we were going or what kind of life we would have. But now I can see all I took for granted: I had a family. I believed that whatever happened, we’d be together.

A policeman blows a whistle and holds his arm in the air, and we understand that we’re to line up. The solid weight of Carmine is in my arms, his hot breath, slightly sour and sticky from his morning milk, on my cheek. Dutchy carries our bags.

“Quickly, children,” Mrs. Scatcherd says. “In two straight lines. That’s good.” Her tone is softer than usual, and I wonder if it’s because we’re around other adults or because she knows what’s next. “This way.” We proceed behind her up a wide stone staircase, the clatter of our hard-soled shoes on the steps echoing like a drumroll. At the top of the stairs we make our way down a corridor lit by glowing gas lamps, and into the main waiting room of the station—not as majestic as the one in Chicago, but impressive nonetheless. It’s big and bright, with large, multipaned windows. Up ahead, Mrs. Scatcherd’s black robe billows behind her like a sail.

People point and whisper, and I wonder if they know why we’re here. And then I spot a broadside affixed to a column. In black block letters on white papers, it reads:

WANTED

HOMES FOR ORPHAN CHILDREN

A COMPANY OF HOMELESS CHILDREN FROM THE EAST WILL

ARRIVE AT

MILWAUKEE ROAD DEPOT, FRIDAY, OCTOBER 18.

DISTRIBUTION WILL TAKE PLACE AT 10 A.M.

THESE CHILDREN ARE OF VARIOUS AGES AND BOTH SEXES, HAVING BEEN THROWN FRIENDLESS UPON THE WORLD . . .

“What did I say?” Dutchy says, following my glance. “Pig slops.”

“You can read?” I ask with surprise, and he grins.

As if someone has turned a crank in my back, I am propelled forward, one foot in front of the other. The cacophony of the station becomes a dull roar in my ears. I smell something sweet—candy apples?—as we pass a vendor’s cart. The hair on my neck is limp, and I feel a trickle of sweat down my back. Carmine is impossibly heavy. How strange, I think—that I am in a place my parents have never been and will never see. How strange that I am here and they are gone.

I touch the claddagh cross around my neck.

The older boys no longer seem so rough. Their masks have slipped; I see fear on their faces. Some of the children are sniffling, but most are trying very hard to be quiet, to do what’s expected of them.

Ahead of us, Mrs. Scatcherd stands beside a large oak door, hands clasped in front of her. When we reach her, we gather around in a semicircle, the older girls holding babies and the younger children holding hands, the boys’ hands stuffed in their pockets.

Mrs. Scatcherd bows her head. “Mary, Mother of God, we beseech you to cast a benevolent eye over these children, to guide them and bless them as they make their way in the world. We are your humble servants in His name. Amen.”

“Amen,” the pious few say quickly, and the rest of us follow.

Mrs. Scatcherd takes off her glasses. “We have reached our destination. From here, the Lord willing, you will disperse to families who need you and want you.” She clears her throat. “Now remember, not everyone will find a match right away. This is to be expected, and nothing to worry about. If you do not match now you will simply board the train with Mr. Curran and me, and we will travel to another station about an hour from here. And if you do not find placement there, you will come with us to the next town.”

The children around me move like a skittish herd. My stomach is hollow and trembly.

Mrs. Scatcherd nods. “All right, Mr. Curran, are we ready?”

“We are, Mrs. Scatcherd,” he says, and leans against the large door with his shoulder, pushing it open.

WE’RE AT THE BACK OF A LARGE, WOOD-PANELED ROOM WITH NO windows, filled with people milling about and rows of empty chairs. As Mrs. Scatcherd leads us down the center aisle toward a low stage at the front, a hush falls over the crowd, and then a swelling murmur. People in the aisle move aside to let us pass.

Maybe, I think, someone here will want me. Maybe I’ll have a life I’ve never dared to imagine, in a bright, snug house where there is plenty to eat—warm cake and milky tea with as much sugar as I please. But I am quaking as I make my way up the stairs to the stage.

We line up by height, smallest to tallest, some of us still holding babies. Though Dutchy is three years older than me, I’m tall for my age, and we’re only separated by one boy in the line.

Mr. Curran clears his throat and begins to make a speech. Looking over at him, I notice his flushed cheeks and rabbity eyes, his droopy brown mustache and bristly eyebrows, the stomach that protrudes from the bottom of his vest like a barely hidden balloon. “A simple matter of paperwork,” he tells the good people of Minnesota, “is all that stands between you and one of the children on this stage—strong, healthy, good for farm work and helping around the house. You have the chance to save a child from destitution, poverty, and I believe Mrs. Scatcherd would agree that it is not too great an exaggeration to add sin and depravity.”

Mrs. Scatcherd nods.

“So you have the opportunity both to do a good deed and get something in return,” he continues. “You will be expected to feed, clothe, and educate the child until the age of eighteen, and provide a religious education as well, of course, and it is our deepest hope that you will grow to feel not only fondness for your child, but to embrace him as your own.

“The child you select is yours for free,” he adds, “on a ninety-day trial. At which point, if you so choose, you may send him back.”

The girl beside me makes a low noise like a dog’s whine and slips her hand into mine. It’s as cold and damp as the back of a toad. “Don’t worry, we’ll be all right . . .” I begin, but she gives me a look of such desperation that my words trail off. As we watch people line up and begin to mount the steps to the stage, I feel like one of the cows in the agricultural show my granddad took me to in Kinvara.

In front of me now stands a young blond woman, slight and pale, and an earnest-looking man with a throbbing Adam’s apple and wearing a felt hat. The woman steps forward. “May I?”

“Excuse me?” I say, not understanding.

She holds out her arms. Oh. She wants Carmine.

He looks at the woman before hiding his face in the crook of my neck.

“He’s shy,” I tell her.

“Hello, little boy,” she says. “What’s your name?”

He refuses to lift his head. I jiggle him.

The woman turns to the man and says softly, “The eyes can be fixed, don’t you think?” and he says, “I don’t know. I would reckon so.”

Another man and woman are watching us. She’s heavyset, with a furrowed brow and a soiled apron, and he’s got thin strips of hair across his bony head.

“What about that one?” the man says, pointing at me.

“Don’t like the look of her,” the woman says with a grimace.

“She don’t like the look of you, neither,” Dutchy says, and all of us turn toward him in surprise. The boy between us shrinks back.

“What’d you say?” The man goes over and plants himself in front of Dutchy.

“Your wife’s got no call to talk like that.” Dutchy’s voice is low, but I can hear every word.

“You stay out of it,” the man says, lifting Dutchy’s chin with his index finger. “My wife can talk about you orphans any way she goddamn wants.”

There’s a rustling, a flash of black cape, and like a snake through the underbrush Mrs. Scatcherd is upon us. “What is the problem here?” Her voice is hushed and forceful.

“This boy talked back to my husband,” the wife says.

Mrs. Scatcherd looks at Dutchy and then at the couple. “Hans is—spirited,” she says. “He doesn’t always think before he speaks. I’m sorry, I didn’t catch your name—”

“Barney McCallum. And this here’s my wife, Eva.”

Mrs. Scatcherd nods. “What do you have to say to Mr. McCallum, then, Hans?”

Dutchy looks down at his feet. I know what he wants to say. I think we all do. “Apologize,” he mumbles without looking up.

While this is unfolding, the slim blond woman in front of me has been stroking Carmine’s arm with her finger, and now, still nestled against me, he is looking through his lashes at her. “Sweet thing, aren’t you?” She pokes him gently in his soft middle, and he gives her a tentative smile.

The woman looks at her husband. “I think he’s the one.”

I can feel Mrs. Scatcherd’s eyes on us. “Nice lady,” I whisper in Carmine’s ear. “She wants to be your mam.”

“Mam,” he says, his warm breath on my face. His eyes are round and shining.

“His name is Carmine.” Reaching up, I pry his monkey arms from around my neck, clasping them in my hand.

The woman smells of roses—like the lush white blooms along the lane at my gram’s house. She is as finely boned as a bird. She puts her hand on Carmine’s back and he clings to me tighter. “It’s all right,” I start, but the words crumble in my mouth.

“No, no, no,” Carmine says. I think I may faint.

“Do you need a girl to help with him?” I blurt. “I could”—I think wildly, trying to remember what I am good at—“mend clothes. And cook.”

The woman gives me a pitying look. “Oh, child,” she says. “I am sorry. We can’t afford two. We just—we came here for a baby. I’m sure you’ll find . . .” Her voice trails off. “We just want a baby to complete our family.”

I push back tears. Carmine feels the change in me and starts to whimper. “You must go to your new mam,” I tell him and peel him off me.