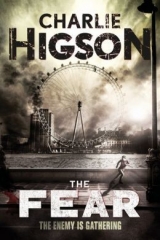

Текст книги "The Fear"

Автор книги: Charlie Higson

Жанры:

Ужасы

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 24 (всего у книги 27 страниц)

62

They never discovered Shadowman’s hiding-place in the burnt-out building, and he’d spent the long night there listening to them feed. St George and his gang first, and then the others, who fought over every last scrap of flesh and skin and bone. Finally, the most diseased, the weakest, had come to the table and Shadowman had had to watch them in the grey light of dawn as they licked the road clean of blood. Now he could see more clearly the mess they’d made. There was almost nothing left of Tom and Kate.

As the day dawned, some of them had started to drift away, first in ones and twos, and then in larger groups. Wandering off to find somewhere to sleep until it got dark again. The last to leave were the toughest, the ones who didn’t fear the daylight, St George and his boys. They trooped up the road past Shadowman’s hiding-place, looking pleased with themselves. St George at the front, his great fat head too heavy for his neck to hold upright. Then Bluetooth and the One-Armed Bandit, followed by Man U and …

Shadowman had to hold back a laugh. His bolt had hit something when he’d fired it into the night. It had hit the last member of the gang. The one he’d been struggling to name. It stuck out of his shoulder – either it was too deeply embedded to pull out, or he simply hadn’t bothered to try. He didn’t look too troubled by it. He almost seemed to wear it with pride. Like a medal. Shadowman wept with joy at this tiny victory. Not only had he wounded the bastard, but he’d given him a distinguishing feature. He was no longer just a faceless stranger.

When you named things you owned them.

A big smile spread over Shadowman’s face as he finally worked out what to call him.

Spike.

63

That bit there was a road. It ran beside the train tracks and led to the forest. Past the forest was the city, with all those houses and parks and fine buildings – the cathedral, the stadium, the row of theatres, the shopping centre. Next to the city was the farm. Where she lived. It was just like the one she’d made playing Farmville on Facebook. The hours she’d wasted on that! She tended her new farm just as carefully now as it hung above her. She planted seeds and pulled up vegetables. She milked the cows and fed the chickens and exercised the horses. Her sheepdog, Baxter, rounded up the sheep. She could look after this place, keep the animals well fed and safe and happy. Nothing bad was ever going to happen here. Not like in the real world. Not like the cold, heartless, unfair, unfair, unfair place London had become. Where she could do nothing to save her friends.

Her imaginary world was warm and sunny and bright. Everyone smiled all the time and there were no wolves to frighten the sheep, no foxes to get into the hen-house, no grown-ups to shoot the rabbits. No grown-ups at all. Anywhere. Not even healthy ones. And her farm was a private place. No one else knew the secret road to get there. There were just the three of them, Brooke, Donut and Courtney, sitting at the kitchen table, eating freshly baked bread and soft-boiled eggs and drinking cold milk. Sitting side by side, laughing and chatting.

Never mind that this farm didn’t exist, nor the city, nor the forest, nor the network of roads, that they were all just made up out of the stains and cracks and blotches that covered the ceiling above her bed.

Never mind …

She could lie there for hours, suspended somewhere between wakefulness and sleeping, staring up and wandering about in that imaginary world. She’d sunk so far into her depression that she’d reached a numb place, where nothing mattered any more. Nothing was real. She was detached from her body, oblivious to the pain that blazed around her wounded head. They gave her painkillers now and then, but they did little to help. She sensed they were rationing them. Pills like these were rare and precious these days. They probably wanted to keep them for their own. They’d stitched her face, though. She had felt them tugging and gouging and gathering her skin together where it had been sliced through clean to the bone across her forehead.

At first she hadn’t known where she was. Hadn’t cared. Had simply drifted in her dream world. Slowly, slowly, however, despite her trying not to, she had started to tune in to what was going on around her. They’d brought her to Buckingham Palace, where David and his followers lived. They’d carried her upstairs to some kind of sick-bay. It was quiet and peaceful in here, lit only by the soft glow of tea candles. Girls came and went, dressed as nurses. It was one of them who had stitched her, a girl called Rose. She seemed to be in charge. She gave Brooke her pills, took her temperature, fed her, took her to the toilet …

How long had she been here? A day? Two days? A week? Years …

She had no idea. Time had ceased to have any meaning for her. She just lay on her back and stared up at the ceiling as the seasons came and went on her farm.

She had to stay up there, among her animals, because there were places she couldn’t go, memories she couldn’t face. Every now and then she settled into a deep calm; she would be floating on pink fluffy clouds counting sheep, sliding on a rainbow, or sitting at that kitchen table with her friends. There were times when she’d feel warm and safe and well fed, cared for, looked after …

And those were the most dangerous times, because her defences would drop and suddenly the memories would come screaming back at her. How Donut and Courtney had come all the way across London to find her. How she had been reunited with them only to have them snatched away from her. The friends she hadn’t seen for a year and had thought must surely be dead. Slaughtered by sickos.

Unfair. Unfair. Unfair.

Tears would well in her eyes and soak her pillow. Sometimes she woke up crying, and one of the nurses would come over and ask her how she was and wipe away the tears and stroke her hair and Brooke could pretend that everything was OK.

She would never reply when they asked her things. She hadn’t spoken a word since she’d come here. Didn’t think she would ever speak again. What was the point? What was the point of anything? Living or dying or talking or laughing …

All she could ever look forward to in the future was a life of pain and loss. They were all just children – what chance did they have? They could play at soldiers, or scientists, or nurses and doctors, but they were just as helpless as the cattle on her farm, the chickens and sheep, they were just farm animals, waiting to be eaten by the grown-ups.

She hadn’t dared look in a mirror at what a mess the mother had made of her face. To make it worse the wound had become infected. The nurses had covered it with disinfectant and antiseptic, but it had burned. At times she thought the infection must be burning right through to her brain. Sending her mad. She thought about Ed, once so handsome, remembered what the cut had done to his face, and she knew that she would look just as bad if she survived. She would be a freak, a monster, like the disease-ruined mothers and fathers who wandered the streets. Was this God’s punishment for how she’d treated Ed?

Or was it just shitty luck?

She knew she must look bad because when Rose and the girls inspected her wound they winced and grimaced and said things like ‘poor girl’.

Poor girl.

She also gathered that her whole face had swollen up from the bruising and infection. Her eyes were puffy and blackened. She must look more like a corpse than the old Brooke. The most beautiful girl on the bus.

They’d wrapped bandages round her head. She suspected it was as much to hide what she looked like as to keep the wound safe. They had to change the bandages all the time as they began to smell.

There was one good thing about being unrecognizable and not talking. Nobody knew a thing about her. Who she was. Where she had come from. David had come in once, glanced briefly at her, before turning away. He hadn’t recognized her and had talked about her as if she wasn’t there. Had told Rose to keep her here as long as possible and not let any of the newcomers see her again, or try to talk to her. That was fine with Brooke, but Rose had questioned him about it.

‘I want this new lot to stay,’ he’d explained in that snooty, slightly impatient tone of his. ‘At the moment they think that the palace is the only option. The less they know about the other settlements the better. Once they realize the benefits of living here, they’ll not want to go anywhere else, but until then we have to be careful. Who knows where that girl’s from, but probably from one of the larger settlements, Westminster or the museum. As I say, the less this new lot know about all that the better. And, besides, doesn’t that girl need rest and calm or something? Isn’t that how it works?’

‘I suppose so, yes.’

‘Good …’

Good.

That girl.

As far as he was concerned she was a nobody. If he ever realized who she was, he would come back to gloat. And probably worse. She knew he’d never forgiven her for abandoning him on Lambeth Bridge during the fire. And it wasn’t just him; there were other boys here who might remember her. The boys from his school who still wore the geeky red blazers.

For now she had to stay hidden, drift off into her cloud world where nobody could find her. And when she was strong enough, if she lived, she would think about maybe trying to get away from here. That was the one spark of life she had left. Getting away from David. When she was tired, when the memories came back to taunt her, she couldn’t care less, would have been happy to die, but now and then that one tiny thought popped into her head, and she felt her heart beat faster. Somewhere deep inside her something was struggling to live.

Gradually, as time passed and the burning in her head faded, she started to listen to Rose and the other girls, the nurses, who talked quietly as they went about their business. She gathered that the kids who’d saved her were from Holloway, in North London, and that David’s second-in-command, Jester, a boy she’d heard about but never met before, had gone off looking for new recruits and brought them back here to the palace. Four other kids had set off with Jester but none of them had returned. Things didn’t look entirely black, though, because the new arrivals were apparently great fighters. Well, she’d seen enough of them in action to know that, hadn’t she? Now David was hoping that they’d help him get rid of some hooligans who’d made camp in a nearby park and were causing a lot of trouble.

All this stuff was going on around her. People with their own lives, their own problems. And it meant nothing to her. She drifted in and out of sleep, lost herself in the marks on the ceiling, and the next thing she was aware of was a boy in the bed next her. He also had a bandage round his head. He, too, had had a blow to the skull. She thought he might be the muscly black kid who’d rescued her at Green Park, but she couldn’t be sure.

He was out cold, completely unconscious. Brooke listened to the girls and picked up that he’d been hurt in a fight with the hooligans.

David came back, this time with Jester. Brooke recognized him from his famous patchwork coat. The two of them talked to Rose, completely ignoring Brooke who might just as well not have been there. David explained that he wanted to keep the boy – his name was Blue – under guard. He left two of his red blazers to do the job. They sat outside the door and made sure nobody came in or out without David’s permission.

The boys didn’t take their job very seriously; they spent a long time in the sick-room chatting with the nurses, flirting, drinking tea, playing cards. One of them was spotty and grumpy, the other one, who had a big nose and was called Andy, seemed quite nice and was obviously pretty bored with being a guard. Listening in on their chat, tuning in to another world, helped Brooke to tune out of her own problems. She could almost imagine that when she closed her eyes she was listening to a play on the radio or something. One of her mum’s boyfriends had listened to Radio Four all the time, and there always seemed to be a play of some sort on. He never worked, just sat at the kitchen table all afternoon rolling fags and listening to the radio. Said it was ‘far superior to television’ and that only morons wasted their time watching TV. The thing was he was a moron himself, happy to sponge off Brooke’s mum who was out at work all day, and the radio drove Brooke nuts.

Now, though, it was a useful, comforting memory of cosier times, and she could pretend that the disease, the sickos, the death and despair, were all just part of a radio series. Maybe, after all, nothing more would go wrong …

64

They’d been following the boy for ten minutes, holding back, not letting him see them. He’d been creeping round the wall of the Buckingham Palace gardens, going backwards and forwards, distracted, as if he kept changing his mind about what he wanted to do. Once he’d tried to climb over the wall, but had quickly given up. The wire and the spikes at the top had defeated him. He’d been round to the front twice, keeping low, and had peered through the railings of the parade ground, making sure he wasn’t seen by the boys on sentry duty in the boxes.

It was a dark night, so it was hard to see him clearly. All they could say for certain was that he was about fifteen, he was wearing dark clothing, he was very thin and his behaviour was odd, confused.

Now he was making a complete circuit of the wall, muttering to himself.

‘What’s he want? Does he want to get in, or not?’

‘I don’t think he knows.’

The boys following him were two more of David’s boys from the palace, their red blazers looking grey in the half-light. They’d been sent out here by Pod as part of the increased security that had been put in place since DogNut and his crew had got out over the wall. The security had been bumped up even further following the attack on the squatter camp and all that had happened since then. These two had missed most of the excitement, but had heard about it. How one of the kids from Holloway had taken on the squatters’ leader, John, in single combat to settle the argument between them and David.

The Holloway kid had won the fight, but Pod worried that the squatters might not stick to their agreement.

Pod had told them that the palace was now on red alert.

Whatever that meant.

Actually, they knew what it meant. It meant their job was as much to stop anyone from getting out as getting in.

‘Do you think he’s from the camp?’ one of the boys whispered.

‘I dunno. Don’t think so. He arrived from the west. He’s alone. He doesn’t look dangerous to me.’

‘Shall we grab him then?’

‘I dunno.’

‘I think we need to talk to him.’

‘After you …’

65

David was sitting at the table in his office, writing up his diary for the day, when Pod knocked and poked his face round the door. David slid the diary under some papers. No need for Pod to know he kept it. Wouldn’t want anyone to get any ideas about reading it. There were too many secrets in there. One day, though, it would be very valuable. His own personal record of events. The sort of thing that would be kept in a museum.

‘What is it?’

‘We have a visitor,’ said Pod, trying to keep from smiling too broadly. He was evidently very pleased with himself.

‘Is it Nicola?’ David asked rather too quickly, sounding more excited than he had intended.

‘No.’

‘Oh … Who then?’

‘A couple of the guards spotted him wandering around in the road outside. Looked like he was trying to get in.’

‘Who is he, Pod?’ said David with growing irritation.

‘He’s from the Natural History Museum.’

‘Oh, right. Anyone we know?’

‘No. But he’s got an interesting story to tell.’

David leant forward over the table and smiled at Pod.

‘Where is he now?’

‘We’re keeping him down in the guardroom out of the way. Apart from me and the two boys who brought him in, nobody knows he’s here.’

‘And they know to keep quiet?’

‘Of course they do. They’re well trained.’

‘It’s just with everything going on here at the moment we have to be very careful,’ said David. ‘I don’t want the new arrivals talking to anyone from the museum.’

‘I know,’ said Pod. ‘But this guy might be just what we need to solve your museum problem big time.’

‘You’re either going to have to bring him in, or tell me more about him, Pod. You can’t keep teasing me like this.’

‘I’ll go and get him.’

‘And get Jester too. He needs to be in on this.’

‘All right.’

Pod hurried out and David stood up. He went over to the windows and looked out towards the gardens. It was black night outside so all he could see was his own reflection looking back at him. Could he dare to hope that all his plans were going to fall neatly into place so quickly? Not that anything was guaranteed. The Holloway kids were a deadly fighting force, but they were difficult to deal with and didn’t like being told what to do. He had their leaders safely tucked away in the sick-bay under armed guard, which was a start. And John was beaten. He finally had the squatters under his control. Nicola would have to stick to her agreement. She might not realize it, but she was his, and all her kids were his too. He rubbed his hands together. If this boy that Pod had found was all he had implied, then maybe the museum kids would be his soon as well.

It was all happening scarily fast, everything at once, but he’d been planning for a long time, setting it all up. That’s what it took. Not violence, not shouting and screaming and running around with a big stick, but careful planning and intelligence. Thinking things through. Organization. So that now he could let all the pieces slip into place.

He’d have a lot more to write in his diary tonight.

No matter. He liked to stay up late. Didn’t need much sleep. Up late and up early was what worked. Some kids liked to sleep all day, but not him. That was no way to get things down.

He grunted. Out of the corner of his eye he’d caught the reflection of one of the paintings. A full-length portrait of some long-dead princess or other. For a moment she had looked like Nicola.

Nicola …

He was trying to keep a cool head and a clear mind, but thoughts of her kept jamming the gears. He remembered her sitting there opposite him at the table. Remembered her getting up and coming over to him. Standing too close. She’d been mocking him, he knew that much, but all the same …

All the same.

He remembered the smell of her, the flecks of gold in her green eyes … Oh yes, he’d thought about her a lot lately. Pictured her standing by his side on the balcony. Pictured her …

Pod came back in. He had a boy with him who looked pale and thin and slightly crazy. There were dark rings round his eyes, as if he hadn’t slept for days. His hair was a mess, and as David watched he scratched his scalp with dirty fingernails, then rubbed his neck. There was an agitated, fidgety feel to him. His gaze flicked around the room. Seeing ghosts in the shadows.

David poured him a glass of water. Handed it to him. He drank it down in one long gulp.

‘This is David,’ said Pod.

‘Yes, I know,’ said the boy. ‘I know who David is.’

‘Were you looking for me?’ David asked. The boy stared at him, sussing him out. He sniffed. Put the glass down carefully on the table.

‘No, not really. Yes, a bit, yes and no.’ He giggled nervously. ‘I wasn’t sure what I was looking for … Something. Something or other. Or both. Or neither.’

‘You’re lucky you didn’t come across any strangers out there,’ said David. ‘Any grown-ups.’

‘Lucky?’ The boy gave David a withering look. ‘For me? Or for them? I kill grown-ups. I destroy them. I see any I’ll strangle them. I’ll kick their balls off. I’ll smash their sick faces into their heads. I’ll stick my knife into their guts and twist it.’

He mimed the action, leaning towards David and breathing foul sour breath over him.

David backed off. ‘Sit down,’ he said, and the boy sat, looking like he could spring up out of his chair at any moment. He was dressed all in black with a slightly grubby roll-neck jumper that he kept fiddling with, picking at the material.

‘What’s your name?’ David asked.

‘Paul,’ said the boy. ‘Paul Channing.’