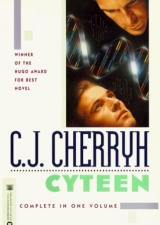

Текст книги "Cyteen "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 30 (всего у книги 61 страниц)

"Do you go to school?"

"Yes, ser."

"Do you like your teachers?"

He was trying to Work her, she decided. Absolutely. She put on her nicest face. "Oh, they're fine."

"Do you do well on tests?"

"Yes," she said. "I do all right."

"Do you understand what it means to be a PR?"

There was the trap question. She wanted to look at uncle Giraud, but she figured that would tell them too much. So she looked straight up at the Justice. "That means I'm legally the same person."

"Do you know what legallymeans?"

"That means if I get certified nobody can say I'm not me and take the things that belong to me without going through the court; and I'm a minor. I'm not old enough to know what I'm going to need out of that stuff, or what I want, so it's not fair to sue me in court, either."

That got him. "Did somebody tell you to say that?"

"Would you like it if somebody called you a liar about who you are? Or if they were going to come in and take your stuff? They can tell too much about you by going through all that stuff, and that's not right to do to somebody, especially if she's a kid. They can psychyou if they know all that stuff."

Got him again.

"God," Justin said, and lifted his eyes above his hand, watching while Giraud got Ari back to her seat.

"She certainly answered that one," Grant said.

Mikhail Corain glared at the vid in his office and gnawed his lip till it bled.

"Damn, damn, damn,"he said to his aide. "How do we deal with that?They've got that kid primed—"

"A kid," Dellarosa said, "can't take priority over national security."

"You say it, I say it, the question is what's the Court going to hold? Those damn fossils all came in under Emory's spoils system—the head of Justice is Emory'sold friend. Call Lu in Defense."

"Again?"

"Again, dammit, tell him it's an emergency. He knows damn well what I want—you go over there. No, never mind, Iwill. Get a car."

". . . watch the hearing,"the note from Giraud Nye had read, simply. And Secretary Lu watched, fist under chin, his pulse elevated, his elbows on an open folio replete with pictures and test scores.

A bright-eyed little girl with a cast on her arm and a scab on her chin. That part was good for the public opinion polls.

The test scores were not as good as the first Ari's. But they were impressive enough.

Corain had had his calls in from the instant he had known about the girl. And Lu was not about to return them—not until he had seen the press conference scheduled for after the hearing, the outcome of which was, as far as he was concerned, a sure thing.

Of paramount interest were the ratings on the newsservices this evening.

Damned good bet that Giraud Nye had leaned on Catherine Lao of Information, damned good bet that Lao was leaning on the newsservices—Lao was an old and personal friend of Ari Emory.

Dammit, the old coalition seemed strangely alive, of a sudden. Old acquaintances reasserted themselves. Emory had not been a friend—entirely. But an old and cynical military man, trying to assure Union's simple survival, found himself staring at a vid-screen and thinking thoughts which had seemed, a while ago, impossible.

Fool, he told himself.

But he pulled out a piece of paper and initiated a memo for the Defense Bureau lawyers:

Military implications of the Emory files outweigh other considerations; draft an upgrading of Emory Archives from Secret to Utmost Secret and prepare to invoke the Military Secrets Act to forestall further legal action.

And to his aide: I need a meeting with Harad. Utmost urgency.

Barring, of course, calamity in the press conference.

iv

"Ari," the Chief Justice said. "Would you come up to the bar?"

It was after lunch, and the Justice called her right after he had called uncle Giraud.

So she walked up very quiet and very dignified, at least as much as she could with the cast and the sling, and the Justice gave a paper to the bailiff.

"Ari," the Justice said, "the Court is going to certify you. There's no doubt who your genemother was, and that's the only thing that's at issue in this Court today. You have title to your genemother's CIT number.

"As to the PR designation, which is a separate question, we're going to issue a temporary certification—that means your card won't have it, because Reseune is an Administrative Territory, and has the right to determine whether you're a sibling or a parental replicate—which in this case falls within Reseune's special grants of authority. This court doesn't feel there's cause to abrogate those rights on an internal matter, where there is no challenge from other relatives.

"You have title to all property and records registered and accrued to your citizen number: all contracts and liabilities, requirements of performance and other legal instruments not legally lapsed at the moment of death of your predecessor are deemed to continue, all contracts entered upon by your legal guardian in your name thereafter and until now are deemed effective, all titles held in trust in the name of Ariane Emory under that number are deemed valid and the individuals within this Writ are deemed legally identical, excepting present status as a minor under guardianship.

"Vote so registered, none dissenting. Determination made and entered effective as of this hour and date."

The gavel came down. The bailiff brought her the paper, and it was signed and sealed by the whole lot of judges. Writ of Certification,it said at the top. With her name: Ariane Emory.

She gave a deep breath and gave it to uncle Giraud when he asked for it.

"It's still stupid," she whispered to him.

But she was awfully glad to have it, and wished she could keep it herself, so uncle Giraud wouldn't get careless and lose it.

The reporters were notmean. She was real glad about that, too. She figured out in a hurry that there weren't any Enemies with them, just a lot of people with notebooks, and people with cameras; so she told Catlin and Florian: "You can relax, they're all right," and sat on the chair they let her have because she said she was tired and her arm hurt.

She could swing her feet, too. Act natural, Giraud had said. Be friendly. Don't be nasty with them: they'll put you on the news and then everybody across Union will know you're a nice little girl and nobody should file lawsuits and bring Bills of Discovery against you.

That made perfect sense.

So she sat there and they wrote down questions and passed them to the oldest reporter, questions like: "How did you break your arm?" all over again.

"Ser Nye, can you tell us what a horse is?" somebody asked next, out loud, and she thought that was funny, of course people knew what a horse was if they listened to tapes. But she was nice about it:

"I can do that," she said. "Horse is his name, besides what he is. He's about—" She reached up with her hand, and decided that wasn't high enough. "Twice that tall. And brown and black, and he kind of dances. Florian knows. Florian used to take care of him. On Earth you used to ride them, but you had a saddle and bridle. I tried it without. That's how I fell off. Bang. Right over the fence."

"That must have hurt."

She swung her feet and felt better and better: she Had them. She liked it better when they didn't write the questions. It was easier to Work them. "Just a bit. It hurts worse now, sometimes. But I get my cast off in a few weeks."

But they went back to the written ones. "Do you have a lot of friends at Reseune? Do you play with other girls and boys?"

"Oh, sometimes." Don't be nasty, Giraud had said. "Mostly with Florian and Catlin, though. They're my best friends."

"Follow-up," somebody said. "Ser Giraud, can you tell us a little more about that?"

"Ari," Giraud said. "Do you want to answer? What do you do to amuse yourself?"

"Oh, lots of things. Finding things and Starchase and building things." She swung her feet again and looked around at Florian and Catlin. "Don't we?"

"Yes," Florian said.

"Who takes care of you?" the next question said.

"Nelly. My maman left her with me. And uncle Denys. I stay with him."

"Follow-up," a woman said.

Giraud read the next question. "What's your best subject?"

"Biology. My maman taught me." Back to that. News got to Fargone. "I sent her letters. Can I say hello to my maman? Will it go to Fargone?"

Giraud didn't like that. He frowned at her. No.

She smiled, real nice, while all the reporters talked together.

"Can it?" she asked.

"It sure can," someone called out to her. "Who is your maman, sweet?"

"My maman is Jane Strassen. It's nearly my birthday. I'm almost nine. Hello, maman!"

Because nasty uncle Giraud couldn't stop her, because Giraud had told her everybody clear across Union would be on her side if she was a nice little girl.

"Follow-up!"

"Let's save that for the next news conference," uncle Giraud said. "We have questions already submitted, in their own order. Let's keep to the format. Please. We've granted this news conference after a very stressful day for Ari, and she's not up to free-for-all questions, please. Not today."

"Is that the Jane Strassen who's director of RESEUNESPACE?"

"Yes, it is, the Jane Strassen who's reputed in the field for work in her own right, I shouldn't neglect to mention that, in Dr. Strassen's service. We can provide you whatever material you want on her career and her credentials. But let's keep to format, now. Let's give the child a little chance to catch her breath, please. Her family life is nota matter of public record, nor should it be. Ask her that in a few years. Right now she's a very over-tired little girl who's got a lot of questions to get through, and I'm afraid we're not going to get to all of them if we start taking them out of order. —Ari, the next question: what do you do for hobbies?"

Uncle Giraud was Working them, of course, and they knew it. She could stop him, but that would be trouble with uncle Giraud, and she didn't want that. She had done everything she wanted. She was safe now, she knew she was, because Giraud didn't dare do a thing in front of all these people who could tell things all the way to her maman, and who could find out things.

She knew about Freedom of the Press. It was in her Civics tapes.

"What for hobbies? I study about astronomy. And I have an aquarium. Uncle Denys got me some guppies. They come all the way from Earth. You're supposed to get rid of the bad ones, and you can breed ones with pretty tails. The pond fish would eat them. But I don't do that. I just put them in another tank, because I don't like to get them eaten. They're kind of interesting. My teacher says they're throw-backs to the old kind. My uncle Denys is going to get me some more tanks and he says I can put them in the den."

"Guppies are small fish," uncle Giraud explained.

People outside Reseune didn't get to see a lot of things, she decided.

"Guppies are easy," she said. "Anybody could raise them. They're pretty, too, and they don't eat much." She shifted in her chair. "Not like Horse."

v

There was a certain strange atmosphere in the restaurant in the North corridor—in the attitude of staff and patrons, in the fact that the modest-price eatery was jammed and taking reservations by mid-afternoon—and only the quick-witted and lucky had realized, making the afternoon calls for supper accommodations, that thoroughly extravagant Changeswas the only restaurant that might have slots left. Five minutes more, Grant had said, smug with success, and they would have had cheese sandwiches at home.

As it was, it was cocktails, hors d'oeuvres, spiced pork roast with imported fruit, in a restaurant jammed with Wing One staff spending credit and drinking a little too much and huddling together in furtive speculations that were not quite celebration, not quite confidence, but a sense of Occasion, a sense after hanging all day on every syllable that fell from the mouth of a little girl in more danger than she possibly understood—that something had resulted, the Project that had monopolized their lives for years had unfolded unexpected wings and demonstrated—God knew what: something alchemical; or something utterly, simply human.

Strange, Justin thought, that he had felt so proprietary, so anxious—and so damned personally affected when the Project perched on a chair in front of all of Union, swung her feet like any little girl, and switched from bright chatter to pensive intelligence and back again—

Unscathed and still afloat.

The rest of the clientele in Changesmight be startled to find the Warrick faction out to dinner, a case of the skeleton at the feast; there were looks and he was sure there was comment at Suli Schwartz's table.

"Maybe they think we're making a point," he said to Grant over the soup.

"Maybe," Grant said. "Do you care? I don't." Justin gave a humorless laugh. "I kept thinking—"

"What?"

"I kept thinking all through that interview, God, what if she blurts out something about: 'My friend Justin Warrick.'"

"Mmmn, the child has much too much finesse for that. She knew what she was doing. Every word of it."

"You think so."

"I truly think so."

"They say those test scores aren't equal to Ari's."

"What do you think?"

Justin gazed at the vase on the table, the single red geranium cluster that shed a pleasant if strong green-plant scent. Definite, bright, alien to a gray-blue world. "I think—she's a fighter. If she weren't, they'd have driven her crazy. I don't know what she is, but, God, I think sometimes, —God, why in hellcan't they declare it a success and let the kid just grow up, that's all. And then I think about the Bok-clone thing, and I think—what happens if they did that? Or what if they drive her over the edge with their damn hormones and their damn tapes—? Or what if they stop now—and she can't—"

"—Integrate the sets?" Grant asked. Azi-psych term. The point of collation, the coming-of-age in an ascending pyramid of logic structures.

It fit, in its bizarre way. It fit the concept floating in his mind. But not that. Not for a CIT, whose value-structures were, if Emory was right and Hauptmann and Poley were wrong, flux-learned and locked in matrices.

"—master the flux," he said. Straight Emory theory, contrary to the Hauptmann-Poley thesis. "Control the hormones. Instead of the other way around."

Grant picked up his wine-glass, held it up and looked at it. "One glass of this. God. Revelation. The man accepts flux-theory." And then a glance in Justin's direction, sober and straight and concerned. "You think it's working—for Emory's reasons?"

"I don't know anymore. I really don't know." The soup changed taste on him, went coppery and for a moment unpleasant; but he took another spoonful and the feeling passed. Sanity reasserted itself, a profound regret for a little girl in a hell of a situation. "I keep thinking—if they pull the program from under her now– Where's her compass, then? When you spend your life in a whirlwind—and then the wind dies down—there's all this quiet—this terrible quiet—"

He was not talking about Ari, suddenly, and realized he was not. Grant was staring at him, worriedly, and he was caught in a cold clear moment, lamplight, Grant, the smell of geranium, in a dark void where other faces hung in separate, lamplit existence.

"When the flux stops," he said, "when it goes null—you feel like you've lost all contact with things. That nothing makes sense. Like all values going equal, none more valid than any other. And you can't move. So you devise your own pressure to make yourself move. You invent a flux-state. Even panic helps. Otherwise you go like the Bok clone, you just diffuse in all directions, and get no more input than before."

"Flow-through," Grant said. "Without a supervisor to pull you out. I've been there. Are we talking about Azi? Or are you telling me something?"

"CITs," Justin said. "CITs. We can flux-think our flux-states too, endless subdivisions. We tunnel between realities." He finished his soup and took a sip of wine. "Anything can throw you there—like a broken hologram, any piece of it the matrix evokes the flux. The taste of orange juice. After today—the smell of geraniums. You start booting up memories to recollect the hormone-shifts, because when the wind stops, and nothing is moving, you start retrieving old states to run in—am I making sense? Because when the wind stops, you haven't got anything else. Bok's clone became a musician. A fair one. Not great. But music is emotion. Emotional flux through a math system of tones and ratios. Flux and flow-through state for a brain that might have dealt with hyperspace."

"Except they never took the pressure off Bok's clone," Grant said. "She was always news, to the day she died."

"Or it was skewed, chaotic pressure, piling up confusions. You're brilliant. You're a failure. You're failing us. Can you tell us why you're such a disappointment?I wonder if anyone ever put any enjoyment loop into the Bok clone's deep-sets."

"How do you do that," Grant asked, "when putting it in our eminently sensible sets—flirts with psychosis? I think you teach the subject to enjoy the adrenaline rushes. Or to produce pleasure out of the flux itself instead of retrieving it out of the data-banks."

The waiter came and deftly removed the empty soup-bowls, added more wine to the glasses.

"I think," Justin said uncomfortably, "you've defined a masochist. Or said something." His mind kept jumping between his own situation, Jordan, the kid in the courtroom, the cold, green lines of his programs on the vid display, the protected, carefully stressed and de-stressed society of the Town, where the loads were calculated and a logical, humane, human-run system of operations forbade overload.

Pleasure and pain, sweet.

He reached for the wine-glass, and kept his hand steady as he sipped it, set it down again as the waiters brought the main course.

He was still thinking while he was chewing his first bite, and Grant held a long, long silence.

God, he thought, do I needa state of panic to think straight?

Am I going off down a tangent to lunacy, or am I onto something?

"I'm damn tempted," he said to Grant finally, "to make them a suggestion about Ari."

"God," Grant said, and swallowed a bite in haste. "They'd hyperventilate. —You're serious. Whatwould you suggest to them?"

"That they get Ari a different teacher. At least one more teacher, someone less patient than John Edwards. She isn't going to push her own limits if she has Edwards figured out, is she? She's got a whole lot of approval and damned little affection in her life. Which would yoube more interested in, in the Edwards set-up? Edwards is a damned nice fellow—damned fine teacher, does wonders getting the students interested; but if you're Ari Emory, what are you going to work for—Edwards' full attention—or a test score?"

Grant quirked a brow, genuine bemusement. "You could be right."

"Damn, I know I'm right. What in hell was she looking for in the office?" He remembered then what he had thought of when they made the reservations, that Security could find them, Security could bug the damned geranium for all he knew. The thought came with its own little adrenaline flux. A reminder he was alive. "The kid wants attention, that's all. And they've just given her the biggest adrenaline high she's had in years. Sailingthrough the interview. Everyonepouring attention on her. She's happier than she's been in her poor manipulated life. How can Edwards fight thatwhen she gets back? What's he got to offer, to keep her interested in her studies, against that kind of rush? They need somebody who can get herattention, not somebody who lets her get his."He shook his head and applied his knife to the roast. "Damn. It's not my problem, is it?"

"I'd strongly suggest you not get into it," Grant said. "I'd suggest you not mention it to Yanni."

"The problem is, no one wants to be the focus of her displeasure," Justin said. "No one wants to stand in that hot spot, no more than you or I do. Ari always did have a temper—the cold sort. The sort that knew how to wait. I'm not sure how far it went, I never knew her that well. But senior staff did. Didn't they?"

vi

They got out of the car with Security pouring out of the other cars, and Ari stepped up on the walk leading to the glass doors, with uncle Giraud behind her and Florian and Catlin closing in tight to protect her from the crush of their Security people and the reporters.

The doors opened. She could see that, but she could not see over the shoulders around her. Sometimes they frightened her, even if it was her they had come to see and even if it was her they were trying to protect.

She was afraid they were going to step on her, that was how close it was; and she was still bruised and sore.

They had driven around and seen the docks and the Volga where it met Swigert Bay, and they had seen the spaceport and places that Ari would have given a great deal to have gotten out to see, but uncle Giraud had said no, there were too many people and it was too hard.

Like at the hotel, where they had spent the night in a huge suite, a whole floor all to themselves; and where people had jammed up in the lobby and around their car. That had scared her. It scared her in the Hall of State when they were stopped in the doors and they started to close while she was in them; but Catlin shot out a hand and stopped them and they got through, all of them.

The Hall of State was the first thing they had really gotten to see at all, because there were all these people following them around, and all the reporters.

It was the way it looked in the tapes, it was huge and it echoed till it made you dizzy when you were looking around at it, with all the people up on the balconies looking down at them: it was real, the way the Court had been just a place in a tape, and now she knew what the room at the top of the steps was going to look like the moment uncle Giraud told her that was where the Nine met.

The noise died down. People were all talking, but they were not shouting at each other, and the Security people had put the reporters back, so they could walk and look at things.

Uncle Giraud took her and Florian and Catlin upstairs where she shook hands with Nasir Harad, the Chairman of the Nine: he was white-haired and thin and there was a lot of him that he didn't give away, she could tell that the way she could tell that there was something odd about him, the way he kept holding her hand after she had shaken his, and the way he looked at her like he wanted something.

"Uncle Giraud," she whispered when they were going through the doors into the Council Chamber, "he was funny,back there."

"Shush," he said, and pointed to the big half-circle desk where all the Councillors would sit if they were here.

It was funny, anyway, to be asking Giraudwhether anybody was a friendly or not. She looked at what he was telling her, which seat was which, and where Giraud sat when he was on Council—that was Science, she knew that: they had driven past the Science Building, and Giraud said he had an office there, and one in the Hall of State, but he wasn't there a lot of the time, he had secretaries and managers to run things.

He had Security push a button that opened the wall back, and she stood there staring while the Council Chamber opened right into the big Council Hall, becoming a room to the side of the seats, with the Rostrum in front of the huge wall uncle Giraud said was made out of stone from the Volga banks, all rough and red sandstone, just like it was a riverside.

The seats all looked tiny in front of that.

"This is where the laws are made," uncle Giraud said, and his voice echoed, like every footstep. "That's where the Council President and the Chairman sit, up there on the Rostrum."

She knew that. She could tape-remember the room full, with people walking up and down the aisles. Her heart beat fast.

"This is the center of Union," uncle Giraud said. "This is where people work out their differences. This is what makes everything work."

She had never heard uncle Giraud talk like that, never heard uncle Giraud talk in that quiet voice that said these things were important. He sounded like Dr. Edwards, somehow, doing lessons for her.

He took her back outside then, where it was noisy and Security made room for them. Down the stairs then. She could see cameras set up down below.

"We're going to do a short interview," uncle Giraud told her, "and then we're going to have lunch with Chairman Harad. Is that all right?"

"What's going to be for lunch?" she asked. Food sounded good. She was not so sure about Chairman Harad.

"Councillor," an older woman said, coming up to them, and put her hand on uncle Giraud's sleeve and said: "Private. Quickly. Please."

It was some kind of trouble. Ari knew it, the woman was giving it off like she was about to explode with worry, and Giraud froze up just a second and then said: "Ari. Stand here."

They talked together, and the woman's back was to them. The noise blurred everything out.

But uncle Giraud came back very fast, and he was upset. His face was all pale.

"Sera," Florian said, very fast, very soft, like he wanted her to say what to do. But she didn't know where the trouble was coming from, or what it was.

"Ari," uncle Giraud said, and took her aside, along by the wall, the huge fountain, and down to the other end where there were some offices. Security moved very fast, Florian and Catlin went with her, and nobody was following them. There was just that voice-sound, everywhere, murmuring like the water.

Security opened the doors. Security told the people inside to go into a back office and they looked confused and upset.

But: "Wait out here," uncle Giraud said to Florian and Catlin, and she looked at them, scared, uncle Giraud hurrying her into an empty office with a desk and a chair. They were going to follow her, not certain what to do, but he said: "Out!"and she said: "It's all right."

He shut the door on them. They were scared. Uncle Giraud was scared. And she didn't know what was going on with everyone, except he took her by the shoulders and looked at her and said:

"Ari, —Ari, there's news on the net. It's from Fargone. I want you to listen to me. It's about your maman. She's died, Ari."

She just stood there. She felt his hands on her shoulders. He hurt her right one. He was telling her something crazy, something that couldn't be about maman, it didn't make sense.

"She died some six months ago, Ari. The news is just breaking over the station net. It just got here. They're picking it up out there, on their comlinks. That woman—heard it; and told me, and I didn't want you to hear it out there, Ari. Take a breath, sweet. Ari."

He shook her. It hurt. And she couldn't breathe for a moment, couldn't, till she got a breath all at once and uncle Giraud hugged her against him and patted her back and called her sweet. Like maman.

She hit him. He hugged her so she couldn't, and just went on holding her while she cried.

"It's a damn lie!" she yelled when she got enough breath.

"No." He hugged her hard. "Sweet, your maman was very old, very old, that's all. And people die. Listen to me. I'm going to take you home. Home, understand? But you've got to walk out of here. You've got to walk out of here past all those people and get to the car, you understand me? Security's going to get the car, we're going to go straight to the airport, we're going to fly home. But the first thing you have to do is get to the car. Can you do that?"

She listened. She listened to everything. Things went past her. But she stopped crying, and he set her back by the shoulders and wiped her face with his fingers, and smoothed her hair and got her to sit down in the chair.

"Are you all right?" he asked her, very, very quiet. "Ari?"

She got another gulp of air. And stared through him. She felt him pat her shoulder, and heard him go to the door and call Catlin and Florian.

"Ari's maman has died," she heard him say. "We just found it out."

More and more people. Florian and Catlin. If all of them believed it, then it was truer and truer. All the people out there. Maman was on the news. The whole of Union knew her maman had died.

Uncle Giraud came back and got down on one knee and got his comb and very carefully began to comb her hair. She messed it up and turned her face away. Go away.

But he combed it again, very gentle, very patient, and patted her on the shoulder when he finished. Florian brought her a drink and she took it in her good hand. Catlin just stood there with a worried look.

Dead is dead, that was what Catlin said. Catlin didn't know what to do with a CIT who thought it was something else.

"Ari," uncle Giraud said, "let's get out of here. Let's get you to the car. All right? Take my hand. There's no one going to ask you any questions. Let's just walk to the car."

She took his hand. She got up and she walked with her hand in Giraud's out into the office and outside again, where all the people were standing, far across the hall; and the voice-sound died away into the distance. She could hear the fountain-noise for the first time. Giraud shifted hands on her, and put his right one on her shoulder, and she walked with him, with Catlin in front of her and Florian on her other side, and all the Security people. But they didn't need them. Nobody asked any questions.

They were sorry, she thought. They were sorry for her.

And she hated that. She hatedthe way they looked at her.

It was a terribly long walk, until they were going through the doors and getting into the car, and Florian and Catlin piling in on the other side, while uncle Giraud got her into the back seat and sat down with her and held her.

Security closed the back doors, one of them got in and closed the doors and the car started up, fast and hard, the tunnel lights flashing past them.

"Ari," Giraud said to her on the plane, moving Florian out of his seat to sit down across the little table from her, once they were in the air. "I've got the whole story now. Your maman died in her office. She was at work. She had a heart attack. It was very fast. They couldn't even get her to hospital."