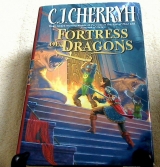

Текст книги "Fortress of Dragons "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 30 (всего у книги 31 страниц)

So Althalen had risen from the ashes. Wind there scoured the stones, flattening the grass that grew where the palace once had stood; above it all the wooden tower stood, Aeself's work, where lightning threatened and wind tore at the sheltering canvas… the women who held that post cried out in terror of the storm, and the tower quaked and swayed, but Tristen willed Aeself's tower to stand against the wind. With a sweep of his arm he willed the lightning away: it was hisland, hislordship, and if he gave it to Crissand, still, he warded it against the enemy. He willed all who were in the place safe, and bade that tower stand.

Owl flew past, a brown streak, and wheeled away on a gust, a skirl of dust that, out of the grass of the ruins of Althalen, became the shape of a man… bits of grass and dust formed all the substance that Hasufin Heltain could command now. He had failed his master, failed his bid for the child. The man of dust had reached after Owl, but fell asunder, no more at last than dust and chaff.

Tristen lifted his hand to recover Owl, who lighted on his arm as lightning chained across the heavens.

He stood in Ynefel, amid shattered timbers, the ruin of all the wonderful stairways that had run like spiderwebs up and up to the loft.

He stood in the courtyard, where Hasufin had been the haunt.

But not the only one.

Dust and leaves blew across the pavings, encountered the cracked wall… and fell, a mere scattering of pieces. Hasufin could not return, not now. His strength was spent.

But the Wind came stealing softly through the open gate. Or had done. Time was always uncertain here, and the Wind came and went unpredictably, like Ynefel's other visitors.

– Well, well, well, said the Wind, here, too, brave prince of Shadows.

– Still here, Tristen said in the foreboding hush.

– But not there, are you? Not in that land where your allies need you… are you, Lord of Ghosts?

Fear touched his heart, fear for Crissand, and for the army he had left to others' leading– but he was not, as Emuin called him, a fool, to glance aside and distract himself with his enemy's chatter. He kept one thing in mind, and the threats and the gusts could not shake him.

– Can I not? Can you not fear me? Others do.

He suddenly had that feeling he had had of nights when Orien's dragons loomed above his bed: and at once he was flung into the gray space in a swirl of cloud. The Wind wrapped about him like a cloak and spun about and about and down.

It left him facing the Edge, where cloud poured like rain down a roof.

– Look in, it said. Do you dare?

And without his bending at all the Edge seemed to open before him. He stared into a dark that reflected shadows and light, and was the image in a rain barrel, no more than that.

It was his own image it cast back, all dark hair and shadow, with the sun at his back, as he had seen himself when first he tried to know his own face.

He drew back in the instant the Wind sought to push him over the Edge. He turned, sword in hand, and faced it with the question he himself had wished to answer:

– Who are you? Do you know? Do you dare look at your own reflection?

_ I dare. A Shape formed itself out of cloud, a young man, mist for a cloak, storm for raiment, and shifting haze for armor. It was a mirror of himself, of Crissand, but neither shadow nor sun: a nameless Shaping of grays and magic, out of its seething clouds of the gray space.

And the challenge it posed was magic, a power breaking free of all law that had ever constrained it, all the wizard-work, all the Lines on the earth, all the bindings ever bound. It breathed in, and on its next breath it might carry all the world away.

And the weapon to counter it was not alone the sword and its spells: it was even more than the Lines of Ynefel's wards, or the Zeide's, or Althalen's, or any barrier of stone laid down in the world: it was all the work of all the wizards and all the Men that had lived their lives in constraint of power and the habit of order.

The Wind gathered force, and gathered force, all for one great effort… it Summoned all who had ever fallen to its lure, all who

had ever gone deep within its embrace and lost themselves, not alone Hasufin Heltain, not alone Orien, or Heryn Aswydd or the hundreds of others without name. It lacked Shape, so it cloaked itself in his likeness, all grays, living magic, the third force, balanced between Shadow and Sun.

– Barrakketh, it whispered, but he would not own that name.

– I know you, it said, as Hasufin had said, but he would not be limited by what it knew.

Instead he recalled an age of watching the suns above the ice, raising the stones of a great, solid fortress to hold the Lines of the World against the ceaseless change of magic.

He recalled the gathering of those who could answer a wizard's call when it came, for a barrier was breached. The unthinkable had happened. Time itself circled around and around that moment, around those few who could keep the gray space in check.

– Five who failed, the Wind taunted him: it was a willful creature, and destroyed without a thought: it changed and made change: that was what magic did. It slid, and shifted, like a step on ice.

– You can only reflect me, he answered it, the untaught truth, for it had Shaped itself in the image of all it knew, all it saw outside the gray void where it existed… it was the changing mirror of all it met: the Book had said these things. That was the dark secret, the one that would not Unfold to him. He saw the gray force, the middle one, the force in the breach.

– Hasufin wanted that knowledge so, mused the Wind. He wanted that Book to know what he had done. He thought there was a way to bind me. He was mistaken. The Sihhë failed. He was doomed.

–No, Tristen said, for in a leap of fear he saw the danger it posed in its accommodation to his Shape: it reasoned in his own voice and he had begun to listen to it. In its gray reflection of himself he saw the chance to learn more and more and more of what he was, and to find what the Shape withheld from him.

But it would gather him in if he listened to it. Yes, it would answer the questions. It would mirror all the world, and bring all his desires within his reach, all encompassed, all answered, all perfect, and complete.

But the world he loved was less orderly, less perfect.

The world he loved defied him and caused him grief, and contained the warmth of the Sun and the voices of friends. It held the smell of rain, the taste of honey, and the softness of feathers.

A throng of foolish birds, a scramble after bread crumbs.

Owl's nip at his finger.

Emuin's frown. Crissand's smile. Cefwyn's wry laughter.

–No, he said a second time, shaking his head. And, No, a third time, and with a sweep of the sword he drew a burning Line between Truth and Illusion.

He stood in the pouring rain on the parapets of Ynefel in the next beat of his heart. The Wind rushed over the walls at him, edged with bitter cold, and tried to hurl him down.

He Called the wards of Ynefel and they sprang up in light… the Lines not only of the fortress, but Lines alight all through Marna Wood, all along the old Road, all along the river shore: Galasien'sLines rose to life, and Lines spun out and out through the woods, the shape in light of the ancient city, recalling what had been, what could not now be.

"Crissand!" Tristen cried, realizing the danger of that slide backward. He hurled himself into the gray space, to go back to all that he had left at risk… but his attempt careened off into the winds. He Called further: now Althalen's wards leapt up, and the blue of the Lines rose up and raced on and on across the land.

At Henas'amef, the Zeide flared bright as a winter moon, and all the Lines of the town and its walls leapt to life. The light of Lines raced along outward roads like dew on a spiderweb, touched villages, touched Modeyneth. Light ran along the foundations of the Wall that Drusenan had raised. Blue fire touched Anwyll's camp, and raced along the bridge, and across the river to the camp, and on to the trail of the army, through woods and meadows.

He had no Place, and had every Place. The lightning chained about him, and the light of the gray place ran along his hand and into the tracery of silver on his sword. He had no wish to do harm. He had no wish to end his existence.

– Pride, pride, pride, the Wind mocked him. It was certainly Mauryl's undoing. So do you inherit his mantle, Shaping? You think you can keep me out?

– You invited me in, he reminded the Wind. I hold you to that.

It disliked that. It strengthened its wards against him. And for the second time the Wind gathered Shape, reflecting him, as if a young man wrapped himself in a cloak of shifting shadow, and glanced mockingly over his shoulder.

– Do you like what you see, Mauryl's creature? Question, question, question everyone, but never the best question… what are you? Mauryl's creature? Mauryl's maker? Come, be brave, ask yourself that question. I'll give you this: we aren't that different, you and I.

He could never resist questions. Questions led him, distracted him, carried him through the world forgetful of his own substance and fearful of what he might find.

But among those questions he remembered the fabric of that cloak… a roiling of shadow and smoke beyond a railing. Then he asked a different, unasked question: why now? Why not Lewenbrook? Why come through Hasufin, until now?

Then he knew what had changed since Lewenbrook. Then he was sure whence it had come… not out of Ilefínian, where it had now taken hold: but it was never lord there in the Lord Regent's domain. The breach had come elsewhere, magic breaking forth from a tangled maze of shadows, repeated attempts to ward it in.

Lines built upon and rebuilt, until its ally sent the lightning down… confounding the Lines that Men had built, breaking a small gap wider. Ilefínian was the second step.

And he had redrawn that Line… there! Tristen said to himself, and with a thought carried himself to the ward he had traced on the stones of the Quinaltine shrine.

Herehe engaged his enemy, and herehe brought the new Line up in brilliant light, in a place of chanting and incense, and sudden consternation.

"Gods!" Efanor cried, armed and armored, amid guards and priests as he faced the intrusion on his long watch. " Amefel!"

"Stand fast!" Tristen said, for the gray space broke forward, rushed at the Line: and when it could not cross that barrier on the new stones, spilled upward like smoke, spiraling up to the rafters. The Wind tugged at the heraldic banners between the columns, rising up and up toward the gap that had once been there, a mended gap that suddenly and with a rending of timbers opened to the sky.

"Amefel!" Efanor cried as timbers crashed like thunder among the benches, splintering wood, resounding on stone. "What's happened? Are we lost?"

"Not yet!" Tristen wheeled the sword about, struck a clanging blow to the Line on the stones, and called the Shadows up and up, until blue fire leapt from the blade to the rafters. Shadows rushed into that breach in the roof, a rift in the wards that had let the gray space rip wide, a Line straight to Ilefínian's unprotected heart.

Owl made a swift passage behind the columns about the shrine, routing a last few Shadows, and rose up, up on the draft.

"Stand fast!" Tristen asked of Efanor, and hurled himself through the gray space, seeking to breach the wards the enemy had made.

But the mews began to remake itself about him, glowing with blue light, row on row of perches, Shadows that raised ominous wings and battered the air, defying him, defying the Lines that now existed, ready to rend and destroy.

But Emuin, besieged in his tower, wind-battered, waved a bony arm and wished him on his way north, as Men measured the heavens.

"The Year of Years, young lord! This age is yours! You, young lord, youclaim it! Do as you must! Go!"

A flock of birds started up at his passage, wings brushing the gray space: his frail, silly companions of lost hours… he was startled by their rise into the mews, and seeing them so frail and foolish against the Shadows, he spread his magic wide to protect them on the wing: he wished them up, and through all hazard—for a way out was what they sought.

The winged ghosts of the mews rushed up as well, but his flock turned in a wide sweep, wings flashing against the roiling dark, by his wish evading the killers. Owl rushed by like a mad thing, losing feathers, himself nearly prey.

– Fly, he wished Owl. And Crissand. And Cefwyn, and all the wizards of Men who had ever drawn a Line against this thing. He followed Owl, tried to thread the needle through the wards of Ilefmnian… and found himself instead flung to the Edge with his back to the brink.

The mirror-youth faced him, the gray space flashing with storm.

Tristen stood fast, going neither forward nor back, calling the light of the gray space into his sword until the silver on the blade burned blinding bright. Truth, one side said, and Illusion, the other, and the line between the two he aimed at the heart of his enemy.

– Shaping of Mauryl, it taunted his defense. Bind me, you upstart? Banish me, do you think? Go back into the dark, foolish Shaping, until you learn my name!

– For him I bind you, Lord of Magic! For Mauryl! And for Hasufin, when he was Mauryl's friend!

The Wind roared over him, an outraged wall of gray, and the force that attempted to form about him, to Shape itself about his shape, sundered itself on the sword's edge, and lost all form. He could not see its fall, or if it fell, but behind him there was nothing but the Edge.

… or the reflection in the rain barrel.

… or the endless rush of wind and cloud into the void.

The wards it had woven, threads stretched from the Quinaltine and wound about Ilefínian… collapsed like a wall going down.

"M'lord," he heard from a great distance. "M'lord, we could truly use your help, if ye hear me."

Thunder cracked. He stood in that hall in Ilefínian with Crissand at his side, and the archers loosed arrows as Crissand gave a wild cry and charged them… battered them with shield and sword all the way to the door, where Crissand stood, sword in hand, glancing out into the hall.

Then back. "Which way?" Crissand asked.

"I've no idea," Tristen said in astonishment, feeling that time had one certain direction now, and that it moved indeed as he willed it. His knees felt apt to give way; and he took two steps, helpless as a child and apt to faint, except he had the echo of Uwen's voice ringing in his ears: it seemed to him now that Uwen had been calling for some time.

Crissand meanwhile had two shafts hanging from the bright sun on his shield and a lively challenge shone in his eyes. Between two heartbeats, it might have been, the loosing of an arrow and its strike.

"Downstairs," Tristen said, remembering the town gates that lay far downhill of the fortress, and suddenly knowing the limits of flesh and bone—that they could not gain the gates by wishing themselves there.

"More are coming," Crissand said at a racket of footsteps on some distant stairs. "Shall we hold here a bit?"

Lord of Althalen, he was, Tristen said to himself. Lord Sihhë he accepted to be.

"Owl!" he called.

Out of thin air and the stones of the wall, Owl flew, and flew past Crissand, out the door.

Where Owl flew, there Tristen knew he should go. Strength came back to his limbs. He settled his grip on his sword, and heard, distantly, not the crash of thunder, but the boom of something battering the doors downstairs.

Sweat ran beneath the helm and streamed into Cefwyn's eyes as he climbed the hill that had been a long, long slope down. The fighting on the hill above him swam in a blur of red mingled with that pale blue that always in his thoughts was Ninévrisë's.

The black banner no longer flew. He was sure of that. He thought that that was indeed Ninévrisë's standard up there with the Marhanen Dragon… but he could not be sure; and to lose the battle now, for want of officers up on that hill, that possibility, he refused to bear: to see Ryssand escape him, he refused; and he drove himself despite the haze of his vision and the ache in his bones.

Black coat on a rider that turned his way: Tasmôrden's man, he thought in alarm, but black was the color of the Prince's Guard as well; and with a pass of a bloody glove across his eyes he confirmed that it was one of his own who had seen him, one of his own who turned toward him, across the corpse-littered field.

More, he knew that blaze-faced horse: it was Captain Gwywyn who came riding in his direction, leaving the battle above, and the fact that Gwywyn came personally reassured him that loyal officers were indeed in command up there, that the fighting was all but done.

With a great relief, then, Cefwyn climbed, using the rocks to help him on his right, though Gwywyn's horse gained ground downslope far faster than made his weak effort climbing at all worthwhile. Gwywyn quickened his pace… then reined back hard, in inexplicable alarm, gazingup.

Cefwyn turned as with a grate and a scrape of stone and metal a heavy weight slid down from the rocks… a man landed afoot in front of him as Cefwyn lifted his sword in defense: an armored man in black, and likewise armed, and familiar of countenance.

"Master crow?" Cefwyn said, forcing his unused voice. "Damn you, you're late!"

"If my lord king hadn't led me a damned downhill chase," Idrys retorted, "I'd have been in better time." A glance gestured back toward Gwywyn, who, Cefwyn saw, had come to a baffled standstill. "That, my lord king, is no rescue."

"Gwywyn?" Cefwyn blinked and saw in Gwywyn's bearing and in Gwywyn's unsheathed sword suddenly not his defense, but a threat, the substance of Idrys' warning of some nights past… Gwywyn: his father's Lord Commander, his father's right-hand man. And if Gwywyn had turned traitor… or if Gwywyn had always been Ryssand's… the three of them were far enough from the rest of the army that no one up there might hear or see what happened in these rocks.

Why should Gwywyn pause? Indeed, why should Gwywyn have doubts in approaching his king, seeing the Lord Commander?

Then Cefwyn saw a reason for Gwywyn to wait, for from the side of the slope nearest the ridge appeared two more men. Corswyndam was one.

"Ryssand," Cefwyn said, with a longing to have his hands on that throat, and a fear that he might not have the chance. "Have you help, crow? We may need it."

"I saw from the heights," Idrys said. "And could not reach that far. But men of mine are aware of him."

"Aware of him!" Cefwyn cried in indignation. "They daren't see either of us leave this field alive!"

"Gwywyn did seem likeliest as a traitor," Idrys said. "I wasn't wrong."

"You might have told me!"

"I had my eye on him."

"Your eye on him, damn you! How long have you known?"

"That he was Ryssand's man? Messages went astray, such as only a handful knew. Lord Tristen informed me of several instances… whence I deemed it a matter of some haste to reach my lord king—and not to make myself evident to the traitors at the same time. I had no evidence."

"No evidence!"

"No more sufficient than had my lord king, since my lord was clearly still temporizing with Ryssand. I spied over the situation. I was never far.—Her Grace, by the by, is well situated in Amefel and sends her love."

"Gods bless!" He was all but breathless, stung to life by the thought of Ninévrisë and unbearably angry at the prospect of dying on this hill, nearly in possession of all he dreamed to have. "Could you not have told me you suspected Gwywyn?"

"I also suspected the captain of the Guelens… who does seem innocent. I'd not ask my lord king's good temper to face one more known traitor in his councils. The half dozen my lord king already knew about seemed sufficient to suggest caution… and I consulted with men of mine, each night. They have their own orders: if Ryssand retreated, he was not to leave this battle."

" Thatis Ryssand, crow. He's left the battle! Where are these men of yours?"

"Uphill, doubtless, where my lord king should be, except he chased downhill and engaged in combat, scattering my men behind him… 'ware, my lord! They're about to charge."

Gwywyn had joined Corswyndam now, and they came ahead: three scoundrels, Cefwyn thought, regretting his shield. He took a solid grip on his sword and reckoned the threat of Ryssand's horse, which was not Kanwy's equal: a heavy-footed, bow-nosed creature he liked no better than its master.

"What was the lightning down there, by the by?" Idrys asked him. "Wizard-work?"

"Hell receiving Tasmôrden," Cefwyn said with a deep breath. For a moment he felt scant of wind, felt the ache in his arms, and then found his spirits rising, for his shieldman was beside him, and that was the most help he had had in days. "I give you your pick, crow."

"I'll take my own traitor, then, and my lord king can have his."

"Done."

Lances lowered. Horses gathered speed.

There was a difficulty in attempting to run through wary opponents, ones who had seen wars before this one, and who had their backs against a barrier neither horses nor lances could pass. Cefwyn waited, waited, and he and Idrys went opposite directions at the last moment, when lances had to strike or lift.

Ryssand tried a sweep of the lance to catch him: Cefwyn flung himself past its reach. Ryssand spun his horse about, its iron-shod feet about to overrun him; but Cefwyn had fought the Chomaggari, with their breed of infighting, infantry half-carried into battle by their cavalry, in among the stones and brush of the southern hills. Ryssand kept turning his horse, his shieldman trying for position, but Cefwyn laid hold of the tail of Ryssand's surcoat and held on, pulling Ryssand sideways, down on his back and under his own horse's hooves as the horse backed from its rider's shifting weight.

The horse dealt the telling blow. The second came on the sword's edge, and Ryssand's head parted his body.

With an anguished shout Ryssand's shieldman forced his way past his lord's horse and rode down at him, and in a moment stretched long and clear as if by magic, Cefwyn turned on his heel and kicked the butt of the fallen lance into the horse's path.

The horse went down, the rider spilled, and lay unmoving when the horse gathered itself dazedly to its feet.

Cefwyn caught a ragged breath then, and lurched half-about toward Idrys, who engaged his predecessor on foot in a noisy bout of swordsmanship, Idrys the younger man and the quicker, but Gwywyn a master years had proved.

Gwywyn knew, now, however, that he was alone, and he began to retreat, perhaps fearing some ignoble blow from the side.

He erred. He died, in the next instant, and Idrys shook the blood from his sword.

Cefwyn proffered him the reins of Ryssand's destrier. "Catch me the guard's horse. I'm too weary to chase him."

"Majesty," Idrys said, between breaths. It was rare to see sweat on master crow, but it was abundant. Idrys looked as if he had run miles, and perhaps he had, but he took the offered reins, and mounted stiffly on Ryssand's bow-nosed horse.

And now four Dragon Guard and two Lanfarnesse rangers came sliding down from the height of the rocks.

"Damn you!" Cefwyn said to the Lord Commander.

" Theywere engaged," Idrys said smoothly, from horseback. "I hurried to my appointment, my lord king. I think more may arrive shortly.—By your leave."

He rode out. In a moment he had caught the guard's horse, and led it back.

"My lord king," Idrys said calmly, handing him down the reins, and by now, indeed, several more rangers stood on the height, and the fighting uphill had come almost to a standstill, a last few of the enemy seeking safety in flight, which Idrys indicated with a flourish of his hand. "Lord Maudyn seems to hold the hill; we have these rocks and several score men of my choosing from place to place along the ridge. I think between us the enemy has met his match."

CHAPTER 8

The battering of the doors gave way to a crash of wood, a clump and a clatter on the stairs, and a worried shout.

"M'lord!" Uwen called, and came running up the steps, shield scraping on the stones, his face white and sweating: it was a far run in armor, but up he came, with Tristen's guard and Crissand's thumping behind him, onto the upper floor of the fortress.

"It's gone," Tristen said, meeting him in that unfamiliar hallway, and such was the relief he felt in saying it that the sky outside the windows seemed lightened. Crissand was beside him. There, too, was a glad reunion, Crissand with his father's guard and their captain.

"The lightnin' cracked an' the sky was blowin' somethin' fierce," Uwen said, out of breath. "But then we said that you was in there an' b' gods them gates was comin' down."

Just so he could imagine Uwen saying it: those great, well-set gates.

"With a ram," Crissand's captain said, "since there was this great old tree gone down in the wood's edge. The lads spied it and we had the limbs off it and up and took it against the gate."

"But the guards at the gate was confused in the banners," Uwen said, "Tasmôrden claimin' the same device. They fell to arguin' amongst themselves whether it was Tasmôrden back again rammin' 'is own gates, or what it all meant… which he's outside the walls, m'lord, somewhere! But Aeself's goin' through the town, street to street, now, tellin' all the folk that it's yourself, m'lord, that it's Amefel come across the river, and they should hunt out the blackguards that's left."

There was a sudden tumult of arms within the halls, somewhere close.

"Our own," Uwen said pridefully. "Them bandits o' Tasmôrden's is goin''t' ground an' hopin' for dark. They're outnumbered by far."

The gray space was open again. It was as if with the passing of the Shadow within the fortress that the sky and the land had lightened and spread wide, and Tristen could both hear and see again within the gray space. And the lords of the south he perceived. And the skirmish in the hall he perceived, and the living folk in the town, with Aeself among them. Cefwyn's forces he perceived.

But Tasmôrden he could not find.

"Cefwyn's east and south of us," he said. "We have to tell him we're here." He led the way down the stairs, down to the lower hall of a fortress he had never entered by its proper doors. Its walls were stone unplastered in its upper courses, and its floor pavings smoothed more by age than art.

And the wooden doors stood ajar, the bright wounds of the wood and a bar standing askew attesting how force and a stone bench had gained entry for his men.

He set a hand on Uwen's shoulder, grateful beyond measure, and they went outside, where Lord Cevulirn stood on the steps with Umanon of Imor Lenúalim, directing riders who occupied the walled courtyard.

"The lost are found," Cevulirn said, seeing them, and Tristen came and embraced the man, embraced stiff and proper Lord Umanon as well, and then had the dizzy notion that hereafter he truly did not know why he lived, or what he should do, or where he belonged. It was as if all that directed him had left, and when he stood back from Umanon he looked outward across the open courtyard, to the open doors, and the walls of houses of a town he had never seen.

He was still lost. Owl had flown up when he came out the doors, and settled now on an absently offered wrist as he gazed over all this motion and tumult of men who took his commands and sought his advice.

But Cevulirn and Umanon knew the governance of a people far better than he knew; Uwen knew the ordering of soldiers in far more detail than he. Crissand knew the needs of the countryfolk far better than he. He looked out across the square and saw Sovrag of Olmern with his men, and Lord Pelumer with him, saw all this array of martial power set now amid a town that had been in the grip of a bandit lord, and saw what appeared to be the common people venturing to the gate, to look inside and wonder what had come on them now.

He knew where he did not belong.

– Emuin? Master Emuin? he asked, anxious for the old man, for Paisi and Ninévrisë and Lusin and all he had left behind; and an answer came to him, at least that master Emuin's charts were in an irresolvable muddle and that baskets and pots and powders were strewn everywhere.

But Emuin was alive, and so was Paisi, and so was Ninévrisë, and they could be here, if they chose. He invited them, if they chose… Eeave Lusin in charge, he said, and showed Emuin the way.

"Where's Dys?" he asked, for he longed to find that other heart he could not touch at a distance: he relied on Uwen, and on Crissand, and sure enough, now his guard had found him, Gweyl and the rest, and would not be shaken lightly from his tracks. "Cefwyn's out there."

"Ye ought to send a messenger, m'lord," Uwen said. "Ye ought to sit here safe and send one of these lads."

"But I won't," Tristen said, with the least rise of mirth. "You know that I won't."

"As I ain't the captain of Amefel any longer," Uwen said, "I can shake free an' ride with ye; an' as your guards has to go, though probably ye can call the lightnin' down on any leavin's of Tasmor-den's lot… still we'll go, m'lord."

Idrys' men had gone out, probing toward Ilefínian, and came back again to say there was a strange assortment of banners before riders on the road: the black banner of the High Kings that Tasmor-den had claimed, in company with the Tower and Checker of the Regent and the Eagle of Amefel, with two and three others less clear to the observers.

"Tristen," was Idrys' pronouncement, where they had established not a camp, but a staying place on the hilltop, under the open sky, a place for dressing wounds and collecting the army in order. "Did I not say this egg would hatch?" Idrys asked. And Cefwyn finding no word: "What shall we do, my lord king?"

What indeed should they do? Cefwyn asked himself somberly. Go to war with Tristen? Call a battered Guelen army to take the field against the friend of his heart, who had claimed that banner?