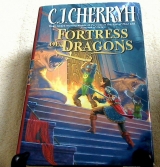

Текст книги "Fortress of Dragons "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 13 (всего у книги 31 страниц)

Aeself had never confessed before that he was in that degree Ninévrisë's kin, never claimed rank in the Regent's house, and in the tangled nature of the noble houses, perhaps he had never held it.

But now he held the post of seneschal of Althalen, at very least, the keeper and the protector of all the loyal Elwynim who made it across the river. He was the defender, and the man who saw to the commonest, most necessary things to keep alive the folk who came to him, against weather and Tasmôrden's men. Auld Syes herself had taken Aeself under her protection, and perhaps safeguarded Crissand, too, against the worst they could do.

"You will have all I can give," he said, "when we come into Elwynor."

"To bring my lord into Elwynor is the honor I want," Aeself said, looking up at him. "Grant me that."

"When you see the fires alight," Tristen said, "then ride to the bridge."

"My lord," Aeself said fervently, and Tristen took the two precious scraps of paper and put them in his belt as he rode away. The well-wishes of all the folk of Althalen were at his back, the banners out in front, and the Amefin guard about him, and a clean, clear sky above all.

" 'At were well done," Uwen said. "Well done, on your own part, m'lord. 'At's a good man, that."

Owl turned up, flying across their path. And Uwen blessed himself, and so, Tristen guessed, did many of the men in his company, but he did not turn to see.

In time, on the way, to Dys' rolling gait, he read the unsealed papers, written with a crude pen in a fine, well-schooled hand.

There were the number of men Aeself had said in the muster, by name and quality, as fairly written as any such account his clerks brought him. The message to Ninévrisë was respectful and sadly informed her of the death of very many of the family, by name, and of the execution or death in battle of friends, by name.

And it told her of the fate of the treasury, put away in cisterns deep in Ilefínian, so, the missive said, the Usurper will have hard shift to bring it out again in the winter.

Aeself Endior, your cousin.

Aeself had been right to have given him the letter unsealed, and at his discretion. Knowing what news it had, he might send or not send—and he did not find it prudent to send the original into Guelemara, where his messengers were in danger. He feared the letter might fall into hostile hands, and inform Ryssand where the missing treasury was… although Tasmôrden might have guessed, and doubtless Tasmôrden had probed the wells: Cook had thought of a similar stratagem to save her utensils during Parsynan's regime, and it was not the first time such things had been done. But in the winter, and near-freezing water, Aeself was right: it was not secrecy that would keep the treasury safe, it was the bitter cold of the water.

And by the time the water warmed enough to lower a man in, he intended the wells might have changed hands again… but not that Ryssand should find some way to the gold first. It was knowledge for Ninévrisë to have, first and foremost. He had a gift to give her, when they met in Ilefínian. He saw the moment clear before him, Cefwyn safe and well, and the Regent's banner flying over the courtyard.

The weather in the Amefin hills around him held clear and the sun warmed his back in a way it had not done since the first of winter. Even the air held a different smell, of moisture and melt, and the snow underfoot lost the crispness of deep cold.

"The weather's taken a turn," Uwen said. "It even smells like spring."

So he imagined, and thought a while, and tried to imagine consequences, as Emuin and Mauryl had taught him.

But at the last he saw there was nothing to gain by waiting.

So gathering up the courage to wish change on the world, and blind to all untried things it meant, he willed that the spring come in earnest and the snow depart.

Nothing seemed to oppose that wish, nothing this near, nothing at this moment opposed him.

He did not trust the ease with which the weather obliged him: he felt his wishes all unfettered, unopposed, unmatched in the world.

Therein, too… he had learned to question his own wisdom.

CHAPTER 11

Pigs in a gate, Cefwyn said to himself, kneeling amid a glow of candles, did not squeal louder or wiggle harder than the recalcitrant barons when they heard the order to bring their men to the bridge at Angesey.

Ryssand was doubtless the loudest… having Cuthan and Parsy-nan in hand, all prepared to confront the king in solemn council, after his defeat at the wedding party, and having raised a certain support for the notion of peace among the barons accustomed to support him. Instead, finding his schemes ignored and the order given to march without his having had a second hearing, Ryssand was so wroth he had struck one of his servants to the ground.

So Cefwyn heard, at least, from Efanor, who retained favor with Ryssand's staff. For himself, after passing the order at night, after the wedding party, and with no consultation or counsel with any of his advisors on the matter… he had declared to all concerned his need to seek spiritual, not mortal, guidance for this war, and he had barricaded himself in the King's Shrine within the Guelesfort.

He took no counsel but his brother's and the Holy Father's, and fasted… was in prayer, seeking the favor of the gods on his holy venture into Elwynor, and could not be disturbed.

Could the barons who carried the banner of orthodoxy and the doctrinists fault him for fasting and prayer?

He knelt and went through the forms of devotion, not that he believed, but that it seemed one thing to create the subterfuge; it was somehow mean and disrespectful, his conscience informed him, to sit in the shrine drinking and eating while he lied to the barons and mocked what good and decent men supporting him thought holy.

So he did go so far as to pray during those long hours, if only the memorized recitals of formal catechism, and as he passed beyond hunger to light-headedness even fancied a certain spiritual elevation… he had had not a bite to eat, and no relief from the chill in this drafty little precinct.

He had no relief from thinking, either, in the tedious hours of kneeling, until at last his unaccustomed knees were beyond pain and his shoulders had acquired an ache that traveled from one aggrieved portion of his back to another like the stab of assassins' knives.

For the first time he knew his body had lost the resiliency of his boyish years; for the first time he accounted how he would pay for all the little follies of youth… at seven, he had cracked his knee falling through the stable-loft floor: that came back to haunt him. The elbow he had affronted in weapons practice not five years gone, that afflicted his shoulder as well. The time Danvy had pitched him off over his head, the slip on the ice when he was twelve, the times his mother had warned him about leaping off the side of the staircase… you'll break your feet, she had said, and he had not remembered his mother's voice clearly in years, but he could now, in this long watch.

In what he fancied was the night he endured a silence so deep he heard echoes he had never heard, as if the Guelesfort itself had a secret life within it, ghosts, perhaps, distant shouts, sharp noises.

It was a shrine his grandfather had dedicated and never used. Efanor had used it, in his childhood, all too often, for a refuge from the shouting and the anger that had filled the royal apartments… shouting and anger that had said very many things a son had not wanted to hear about his mother.

To this day Cefwyn wanted not to think about it, not wishing to remember the worse aspects of his father, who had found fault in both the mothers of his sons. In the death of his own mother and his father's preoccupation with a new wife, he had found alternate escapes, Emuin's study among them, and far less savory nooks of the Guelesfort and the upper town. A brother's at first grudging acceptance had sustained Efanor during the quarrels, the reconciliations, the tirades and the sorrows of hismother's marriage, for no woman at close range could escape their father's eternal discontent. But when Efanor's mother had died, this echoing silence was the place that had consoled Efanor.

Efanor, the younger, bereft too early of a mother he had adored, and led far too often into sin by his rebellious elder brother, had seemed to lose heart somewhere in the extravagance of mourning afterward, being at that age boys began to think more deeply and ask themselves questions. Efanor had found peace first by retreat to this place of cold stone and then by agreement with their father– finding a father's doting on him a great deal safer than the tirades and angers that came down on his brother's head.

And perhaps he'd just grown tired. Cefwyn could find no way to blame him… Efanor, for whatever reason, had spent his adolescent hours in this room, thinking, in a state of mind Cefwyn only now understood. Thinking, as no boy who valued his freedom or his reason should have to think, led by the priests into self-doubt and fear. The Quinalt attributed evil to evil actions. Efanor's mother had died, a sister stillborn. Was that not evil? And had Efanor's sin and rebellion not caused it all? And was their father not quieter now, and grieving, and did not their father need him?

Peace ought to come of this self-questioning, so the priests avowed. But that was not what came of Cefwyn's vigil: rather it was anger at their father, understanding of his brother such as no other place had taught him.

He found anger at Ryssand, too, who had seized on Inareddrin's weaknesses, fed his furies, undermined all trust that might ever have existed between Inareddrin and his eldest son, and perhaps—though he could not find the proof—dealt with Heryn Aswydd in the plot that had sent Inareddrin and almost Efanor to ambush and death.

Had not his own letter had a part in it—his revelation to his father that he had found in Tristen the Elwynim King To Come… and had bound him in fealty?

Gods, did Ryssand know thatmatter, and could Ryssand keep silent on it if he did?

Doubtless not.

Patently not.

But of causes that had brought Inareddrin to that fatal battlefield, it was not his letter. It was nothis letter, but Ryssand's undermining his father's trust, it was Heryn Aswydd's feeding that fear, secretly reporting to his father…

He felt the numbness growing in his back, as pain passed beyond limits. And pain in his heart diminished. He was not his father's murderer. He had almost saved him. Almost. Fate, or wizardry, or whatever guided the affairs of Ylesuin these days, had snatched responsibility out of his hands, and then snatched Tristen, too.

Unfair, but necessary, perhaps. There was no one less blamable for the ills of the court—ills that would not even reach Tristen's understanding in Amefel—or that might have reached it, to Cuthan's discomfort.

Tristen, unlike his king, had not a second's hesitation in dealing with the unwholesome. Tristen had never learned to negotiate: there was the difference, while He had grown up negotiatingfor his fa-ther's affection. Emuin had another boy now. He was glad of that jealous, but glad; and swore if the boy was not grateful, he would' bring the wrath down on the lad.

He had had the benefit of Emuin's teaching. Of Annas' patient management. They had saved him from going down Efanor's road.

And there was Idrys. Thinking on it, in this long meditation on those who had shaped his life and brought him to this moment, he was not sure he was fond of Idrys. It was hard to be fond of the man, in the way it was hard to love a honed blade—but rely on it? Absolutely.

One need not grow maudlin, over Idrys least of all.

Yet… was there nothing for all the years, all the trust, all the hard duty, and all the concentration of a life bent only on saving his? The Crown and the kingdom owed this man more than he had ever gotten… he relied on Idrys, repository of all the unpleasant confidences a monarch could make to no one else, not his pious brother, not his wife, not his best friend's gray-eyed innocence; and thinking on it, damn it all, he wasfond of Idrys, though he could never say so.

Idrys was out at this very moment, having necessarily extracted his last reliable spy and resource from within Ryssand's house, trying to find out what Ryssand was up to from less dependable, external sources. While the king was at his prayers the king's right hand was at work steering the events his order had set in motion, and if things outside this chamber had been going contrary to his orders, Cefwyn had every confidence that no sanctuary would deter Idrys from reporting.

Efanor came and went, however. As near kin, Efanor brought him the water custom allowed… and brought his own reports of the barons' answer to his call to arms, barons who, deprived of access to the king, sought alternative routes of information and protest, barons who, still uncertain as to where Efanor himself stood, revealed more than they knew.

And on this day, too, Efanor came in very softly, still making quiet echoes, and sat down near him on a prayer bench.

"Marisal will march," Efanor relayed to him. "Osanan is contriving excuses and wishes to hear the peace treaty."

Cefwyn heaved a sigh. Of the nineteen provinces of Ylesuin, five were indisputably with Tristen, four were marginally with him, five at least dared stand with Ryssand, and the rest… danced an intricate step in place.

"Guelessar?" he asked. Efanor himself was duke of Guelessar.

Efanor hesitated the space of a breath, head bowed. "Guelessar is a title," Efanor said, the truth both of them knew: that his power was not the real power in the province, only a title that gave him estates and honor. He had very little governance over the lesser lords who administered the districts. "The lords inGuelessar are meeting and have been meeting and two at least have sent messages to Ryssand. For my word, at my order, they will march, will they, nil they." Then Efanor added, the bitter truth, but honest: "How reliable they will be to go to the fore of a battle, and how reliable to stand… that remains to be seen."

"Will we know that of any men on the field, until the moment comes? Relieve yourself of guilt on that account. Gods, gods, that I ever dismissed the south!"

"If you'd kept the southern barons here in court, there'd have been civil war, and you know it."

All too well, though he hadn't known it when he'd called on the south to defend their border before his father's body was cold in his grave.

He had soared at the height of his power when he had stood on Lewen field, victorious over the sorcerous enemy. He had had a tattered and battered army, but five provinces of the nineteen all devoted to a newly crowned king, the likelihood Panys and Marisal and Marisyn would join him in a drive north, and the blessing of the Lady Regent of Elwynor into the bargain, not to mention the likelihood some of her provinces would join them an effort to go straight to her capital and end all the war.

But his southern army had been tired, winter threatened… and he had been king in deed only to half his kingdom.

Crowned in the south, heady with the support of barons ready for action, filled with the desire to restore his newfound beloved to her throne—and, he had to admit, to impress her—he had instead come north to claim the heart of his kingdom, this, in the foolish confidence he could take up all his father's alliances intact. Then, he had thought, he would have had power enough in his hands to assure a well-conducted campaign in the spring with minimal losses on either side.

But he had discovered that his father's compromises with the north had been more extensive and more damaging to the Crown's authority than ever he had suspected. Earliest, he, too, had taken the advice of Murandys and Ryssand, his father's trusted advisors, first of all in appointing Parsynan as viceroy over Amefel, and in so doing, he had fallen into the pattern and embroiled himself in his father's compromises.

He had, with the aid of his friends and advisors, old and new, worked his way to real power: he had wagered everything on the matter of his marriage and gained the Quinalt's approval. He had lessened Ryssand's influence. Now after handling the rebel barons roughly, he set a test for all the north: march in a blizzard, march in defiance of all sanity, march in defiance of the enemy's lying peace offer… or refuse and stand in rebellion to the Crown while the battle flag was flying.

He would be king in truth, or not at all—that was his determination. He would not spend a lifetime catering to fools or compromising his way into his father's situation. He grew aware of his silence, aware of Efanor's eyes studying him, and when their eyes met, Efa-nor said:

"They did listen, Cefwyn. They did hear you. Whatever they decide, your arguments for this action were not wasted."

Efanor knew what he gambled, as perhaps no other could—Efanor who, if he went down, would have to deal with Ryssand in his own way—a different way, perhaps, with a necessarily diminished force, in a vastly changed kingdom.

Thus far he had Tristen uniting five provinces in his name, while he as king could claim only three as solid, one of them Llymaryn– Sulriggan's province, gods save him, Sulriggan, as self-serving a pious prig as ever drew breath, a man with no stomach for fighting—but even less for being left without royal protection: he sided with the Crown because Ryssand hated him for his weathercock swings of loyalty. Therewas his sudden source of courage.

Panys he could trust absolutely. He suspected that Marisal might have moved more quickly to join him because Sulriggan had, being a neighbor, but he still gave the lord of Marisal all due credit, as a man who would not break his oath of fealty. It was a sparsely populated province, with fewer men under arms, but the lord being a devout man and a decent one, he gathered himself and marched.

Those three he had, yet he could not even claim the undivided enthusiasm of his own brother's province of Guelessar, in which the capital sat, in which they now were. It was not surprising, perhaps, since Guelessar was the hotbed of politics of every stamp andthe seat of the Quinaltine, and could no more make a decision than the council and the clergy could.

But, gods, that was difficult to hear, and it was difficult for Efanor to report.

"I would think," Efanor said quietly, "that you have prayed here as long as profits anyone, and it may be time now to come out and hold council. Your captains have readied the army to move. What more can there be? If you ordered such as you have to march now, you might frighten the likes of Osanan into joining you."

He saw his brother in the light of half a hundred candles, modestly dressed as always, but with a certain elegance: whence the gold chain about his neck, that did not support the habitual Quinalt sigil, but rather a fine cabochon ruby? Had he seen Efanor without that sigil in the last year?

And whence the rings on his fingers, and the careful attention to his person? Had this worldliness begun to happen, his brother attiring himself to draw a lady's eye, and he not seen it?

He stared, entranced and curious, seeing in this suddenly handsome and elegant younger brother the flash of wit as well as jewelry, the spark of a man's soul as well as a saint's. This was his successor, if it had to be. This was the continuance of the Marhanen, absent an heir of his own body, staunch in loyalty and awakening to the power he had.

There was hope in his brother.

"Also," Efanor said, "I have some concern for Her Grace."

"She's not fasting!" He would not let her fast, not with the chance she was with child. That had meant she was alone for her devotions, except for Dame Margolis, who ran her household.

Efanor seemed abashed. "Her Grace has reported the morning sickness to her maids."

He was appalled. The maids gossiped in every quarter. Ninévrisë knew better.

Then he was sure she did know better, and intended to break the news unofficially—deliberately, with calculated effect. Rumor would chase rumor through the halls. When Tarien's secret became a whisper, afterthe whispers about Ninévrisë's, it would only be meaningful in the context of Ninévrisë's secret. Women's secrets would battle one another for weeks in the back corridors before they both came to light in council; and lords, again, would take sides.

But before that, the army would march. Thatmight be in her mind.

"Likely her stomach's upset," Cefwyn said, trying to make little of what men ought not to take note of—yet. "So is mine, for that matter. Ryssand is a bane to good digestion."

"Whether it's true," Efanor said, "I am no judge. But it must be end to end of town by now. And in the people's mindstheir own prince will be the firstborn. Your lady is a very clever woman."

"Their own prince." He kept his voice muffled. He had his guard outside, but he wanted no report of crows of laughter and loud voices to come out of his solemn retreat. He could not believe it. He had counted up the days since their wedding night, and it was possible, but only scantly so. It was too much to expect, too soon. "But if it's not true_ if she's made this up only because of the Aswydd woman…"

"She surely wouldn't."

"We have scarcely enough time together… three months, three months, is it not, to be sure?"

Efanor blushed, actually blushed. "I believe women know signs of it, besides the sickness, and there's a chance she's right. Besides…" Efanor added anxiously, "her father was a wizard, no less than the Aswydds. So couldn't she—?"

"I honestly don't know what she could and couldn't. She could be mistaken."

"But if she's deceived herself," Efanor said, "you'll be in Elwynor and maybe in Ilefínian before anyone knows it. Leaves don't go back on the tree. Isn't that what grandfather used to say? You'll haveElwynor."

" Shewill have Elwynor," he reminded his brother.

"To the same effect, is it not?"

By the time anyone knew whether there was a prince to come, the war and the outcome of it would have been settled… except that knotty question of inheritance. Had Ninévrisë thought of that when she confided in a maid?

Or had the sickness been real, and the confidence in the maids a necessity?

And would not the child remove Efanor and all his line from the succession? Perhaps Efanor hoped for it. Perhaps he saw it as he would, as his chance of freedom.

"It will open a battle in the council," he said to Efanor. "To loose this, on her own advice—"

"There is the chance," Efanor said soberly, "that it was the truth, and the sickness was no sham."

"And if it is, she should not ride!"

"Where shall she stay?"

"I would protect her."

"But the rumors would fly. And there would be danger."

"These are good Guelenmen, most. It's Ryssand who's poisoned the well."

"He still thinks he has the advantage," Cefwyn said. "And damned if he does. He will march. Cuthan's head is in jeopardy, Parsynan's with it. I long to say the same of Ryssand, but his obediencewould serve me better. I don't need the other two."

"Don't trust him. Never trust him."

Cefwyn laughed, bitterly, and hushed it, because of the still and holy precinct. "Trust? and this the father of your prospective bride? I trust him only to make mischief, and I shall neverallow you to make that sacrifice, I tell you now. I'll have none of Ryssand in the royal house, in the blood, in the bed, in the intimate counsels. No! don't nay me. I have had unaccustomed time to think, and I will not have that girl attached to you. If I should fall—don't marry her. If I come back, by the gods, you won'tmarry her. I love you too much. "

He surprised Efanor, who looked away and down, and seemed affected by what he had said. He hoped Efanor believed it.

"And I, you," Efanor said at last, "but what other use for a prince who'll never rule?"

"Don't say you'll never rule. War is—"

"Don't say that! And don't talk of falling. The gods listen to us in this place."

"The gods listen to us everywhere or nowhere. It's common sense I make provision. Every farmer who marches with the levy knows to instruct his wife and his underage sons. Shall I do less? She'll ride with me. I know there's no stopping her. And if you rule, promise me Ryssand won't live to see the next day's sun. Marry that chit of his to some farmer. Breakthat house. It will be a detriment to you."

Efanor looked about him as if he feared eavesdroppers. "Not here," Efanor said. "I beg you don't say such things here."

Efanor revered this place, his refuge, his place of peace, the source, Cefwyn suspected, of all Efanor's fancies concerning the gods and the means by which Jormys and then Sulriggan had secured a hold on his brother. And Efanor wished it not to be profaned with talk of killings.

"I respect my brother's wishes," Cefwyn said. "Respect mine. For the good of Ylesuin—promise me."

"I do," Efanor said, and his face was pale when he said it… damning himself with the promise of a murder, so Efanor would see it.

"You're no priest. You're a lord of Ylesuin, you're the duke of

Guelessar, my heir, and justiceis in your hands, a function of the holy gods, the last good advice the Patriarch preached to me. Murder isn't in question. Justiceis."

"Idrys argues much the same," Efanor said. "And constantly. Yet you will not hear him."

"Caught in my own trap," Cefwyn said.

"Yet if you kill Ryssand—"

"Merry hell," Cefwyn said, and Efanor gasped at the affront. "So to speak," Cefwyn said. "And my wife may be with child. Thatwon't please Ryssand either, especially as he wishes me to die childless and his darling Artisane to bear you an heir. Tarien Aswydd, meanwhile, will bring forth my bastard son, a wizard and a prince of the south, an aetheling. I can't think Ryssand will dance for joy at that, either, although who can say what he'll find to object? Any complaint will serve. He brings them like trays of sweetmeats… here, pick one you like."

"Pray the gods for help. Usethe time you have here. Trust them. And come out and lead the kingdom."

"Dear Efanor." It was on his lips to say wake from your dream, but he could not spoil his brother's faith, not when it was bound to lead to quarrels, and he needed quarrels least of all. "Dear Efanor. I trust you. Ask the gods for me. I'm sure you're a voice they know far better than mine."

"I do. Nightly. And have." Efanor glanced down… had always had the eyes of a painted saint as a boy, and did now as a man, when he looked up like that. "I hated you when Mother died, and I prayed for forgiveness. I wanted to love my brother, and I prayed for that. I wanted not to be king, and I wanted not to marry, and I prayed for that. By now I must have confused the gods. So they give me Artisane."

It was the most impious utterance of humor Efanor could manage, brave defiance of his fears in this overawing place, and Cefwyn managed to laugh.

"I wanted my freedom and they gave me the crown," Cefwyn said. "Both of us were too wise to wantto rule, and thus far, you've escaped."

"Only so I go on escaping, and you keep your head on your shoulders, brother. If Ryssand harmed you, yes, I would kill him with my own hands. I have only one brother, and can never get another. I don't care to be king. I care that you have a long, long reign, and I wish Ryssand nothing but misery. I canbe angry. I canbe our grandfather."

"Oh, I know you can be angry! I knew you beforeyou became a saint."

"Don't laugh at me."

"I never laugh at you. Come, come—" He held out open arms. "As we did before we were jealous. As we did when we were young fools."

"Still fools," Efanor said, and embraced him, long and gently, then gazed eye to eye and in great earnestness. "You need to call the council. You've shown the loyal from the doubtful. Now reward the loyal and chide the rest. And gods save us, master crow reports he doesn't think Ryssand knows yet about the Aswydds."

That was a vast relief. "He's sure."

"He doesn't thinkso. That's as far as he'll go."

"Will you carry a message to Ninévrisë? Can you?"

"I'm a pious, harmless fellow. You know I can go anywhere without scandal."

"Tell her everything we've said. Tell her I love her beyond all telling. Make her understand. Tell her be no more indiscreet than she's been."

"I've no difficulty bearing that message. Will you hold council?"

"Oh, yes," he said. "Our prayers are done. Hers and mine. I need her by me. Tell her… tell her I'll see her in the robing room, beforehand. Two hours hence. Make her know I love her. A man belongs with his wife, after all I've done amiss—and what have I had to do? Be here, separate from her! And if she's ill, where am I? Holding council! Reasonable and wise she may be, but when a gut turns, wisdom has nothing to do with it.—Ask her if it's true."

"I can't ask her that!" Efanor was honestly appalled. "Don't ask me to ask her that!"

"The robing room. Two hours. I'll ask her myself." He clapped Efanor on the arm. "Away. Carry messages. And be there, in the robing room, yourself."

The robing room held no privacy, and hardly space to turn, with the Lord Chamberlain and the pages and the state robes on their trees, the king's and the Royal Consort's, stiff with jewels and bullion. It was of necessity the red velvet embroidered with the Dragon in gold, a stiff and uncomfortable Dragon that reminded a man to keep his back straight; and pages buzzed about with this and that ring of significance, the spurs, that were gold, the belt, that was woven gold, and the Sword of office, the belt of which went about him all the while he fretted and had no word yet of Ninévrisë.

Then the door opened, and Ninévrisë came in, wearing the blue of Elwynor, with the Tower in gold for a blazon, like a lord's, on her bodice, and the black-and-white Checker for a scarf about one shoulder. He had never seen it, had no idea by what magic the women's court had created such Elwynim splendor… Dame Margolis, perhaps, who arrived close behind her. Therewas the likely one, the one who would have stayed up nights to accomplish it; and, nothing of what that array meant was wasted on him, nor would the meaning miss its mark in hall.