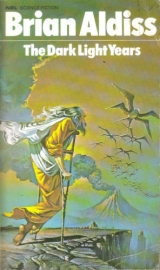

Текст книги "The Dark Light Years"

Автор книги: Brian Aldiss

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 6 (всего у книги 9 страниц)

Manna and his disciples demonstrated that it was possible to live without all this needless luxury ("dirt" was another term they used for it). The cleanliness was evidence of progress. That in the modern revolutionary age, mud was bad.

In this way, the revolutionaries had turned necessity into virtue. Working in the wastes, far away from the wallows and their sheltering ammps, mud and liquid had been scarce. In that austerity had been born their austere creed.

They went further. Once he had started. Manna Warun developed his theme, and attacked the established beliefs of the utods. In this he was aided by his chief disciple, Creezeazs. Creezeazs denied that the spirits of utods were born into their infant bodies from the ammps; he denied that a carrion stage followed the corporeal stage. Or rather, he could not gainsay that the bodily elements of the corporeal stage were absorbed into the mud and so drawn up again into the ammps, but he claimed that there was no similar transference for a spirit. He had no proof of this. It was just an emotional statement obviously aimed at getting the utod away from their natural habit; yet he found those who believed him.

Strange moral laws, prohibitions, inhibitions, began to grow up among the believers. But it could not be denied that they had power. The cities of the wastes to which they withdrew blazed with light in the dark. They cultivated the lands by strange methods, and drew strange fruit from them. They took to covering their casspu orifices. They changed from male to female at unprecedented rates, indulging themselves without breeding. All this and more they did. Yet it was not noticeable that they were exactly happier – not that they preached happiness, for their talk was more of duty and rights and of what was considered good or bad.

One great thing that the revolutionaries achieved in their cities stirred everyone's imagination.

The utods had many poetic qualities, as their vast fund of tales, epics, songs, chants, and were whispers show. This side of them was touched when the revolutionaries built some of their machinery into an ancient ammp seed and drove it into and far beyond the skies. Manna Warun went in it Since pre-memory days, before mindsuckle had made the races of utod what they were, the ammp seeds had been used for boats with which to sail to less crowded parts of Dapdrof. To sail to less crowded worlds had a sort of crazy appropriateness in it. Down in the wallows, the complicated nexi of old families began to feel that per-haps after all cleanliness had something. The fifteen worlds that circled about the six planets of the Home Cluster were all visible at various times to the naked eye, and hence were known and admired. To experience the thrill of visiting them might even be worth renouncing "dirt".

People, converts and perverts, began to trickle into the cities of the wastes.

Then something odd happened.

The word began to get about that Manna Warun was not all he had made himself out to be. It was said that he had often slid away to indulge himself in a secret wallow, for instance. Rumours spread thick and fast, and of course Manna was not there to deny them.

As the ugly rumours grew, people wondered when Creezeazs would step forward and clear his leader's name.

At last, Creezeazs did step forward. Heavily, with tears in his eyes, speaking through his ockpu orifices only, he admitted that the stories circulating were true. Manna was a sinner, a tyrant, a mud-bather. He had none of the virtues he demanded from others. In fact, though others – his friend and true disciple Creezeazs in particular – had done all in their power to stop him. Manna had gone to the bad. Now that the sad tale had emerged, there was nothing for it. Manna Warun must go. It was in the public interest. Nobody, of course, would be happy about it; but there was such a thing as duty. People had a right to be protected, otherwise the good would be destroyed with the bad.

Hardly a utod liked all this, although they saw Creezeazs' point of view; Manna must be expelled.

When the prophet returned from the stars, there was a reception committee waiting for him on the star-realm-ark field.

Before the ark landed, trouble broke out A young utod, whose shining but alarmingly cracked skin showed him to be a thorough-going Hygienic (as the Corps of the Revolution were currently calling themselves), jumped up on to a box. He deretracted all his limbs and cried in a voice like a steam whistle that Creezeazs had been lying about Manna to serve his own ends. All who followed Creezeazs were traitors.

At this moment, an unprecedented event occurred, occurred even as the star-realm-ark floated down from the sides: fighting broke out, and a utod with a sharp metal rod hastened Creezeazs on to the next stage of his utod-ammp cycle.

"Creezeazs!" gasped the third Politan.

"What make you mention that unfortunate name?" inquired the Cosmopolitan.

"I was thinking about the Revolution Age. Creezeazs is the first utod in our history to be propelled along the utod-ammp cycle without goodwill," Blug Lugug said, coming back to the present.

"That was a bad time. But perhaps because these thin-legs also seem to enjoy cleanliness, they also hasten people round the cycle without goodwill. As I say, they are bad in a healthy way. And we are their random victims.”

Blug Lugug withdrew his limbs as much as possible. He shut his eyes, closed his orifices, and stretched himself until his external appearance was that of an enormous terrestrial sausage. This was his way of expressing priestly alarm.

There was nothing in their situation to warrant the cosmopolitan's extreme language. True, it might become rather dull if they were kept here for any length of time -one needed a change of scenery every five years or so. And it was thoughtless the way the lifeforms removed the signs of their fertility. But the lifeforms showed evidence of goodwill: they supplied food, and soon learned not to bring items that were unwelcome. With time and patience, they might learn other useful things.

On the other hand, there was this question of bad. It was indeed possible that the lifeforms had the same sort of madness that existed in the Revolution Age of Dapdrof. Yet it was absurd to pretend that, however alien they might be, these thinlegs did not have an equivalent evolutionary cycle to the utodammp cycle; and this, being so fundamental, could only be something for which they would have a profound respect – in their own peculiar way, naturally.

And there was this: the Revolution Age was a freak, a mere flash in the pan, lasting only for five hundred years -half a lifespan – out of the hundreds of millions of years of utodammp memory. It would seem rather a tall co-incidence if the thinlegs happened to be undergoing the same trouble at this moment.

It was notorious that people who used violent words like bad and random victim, the very words of madness, were themselves verging on madness. So the Sacred Cosmopolitan. ...

At the very thought, the Politan quivered. His fondness for the Cosmopolitan was deepened by the fact that the older utod, during one of his female phases, had mothered him. Now he stood in need of consolation by the other members of his wallow; clearly, it was time they were get-ting back to Dapdrof.

That implied that they should speak with these aliens and hasten their return. The Cosmopolitan forbad communication – and quite rightly – on a point of etiquette; but it began to look more and more as if something should be done. Perhaps, Blug Lugug thought, he could get one of the aliens on his own and try to convey some sense to it. It shouldn't be difficult; he had memorized every sentence they had spoken in his presence since their arrival in the metal thing; although it made no sense to him, it should be useful somehow.

Pursing one of his ockpu orifices, he said, "Wilfred, you don't happen to have a screwdriver in your pocket, do you?”

"What's that?" asked the Cosmopolitan.

"Nothing. Thinlegs-talk.”

Sinking into a silence that held less cheer than usual, the third Politan began to think about the Revolution Age, in case it had any useful parallels with the present case to offer.

With the death of Creezeazs and the return home of Manna Warun, more trouble had begun. This was when bad had flourished at its grandest. Quite a number of utods were thrust without goodwill into the next phase of their cycle. Manna, of course, returned from his flight in the star-realm-ark very vexed to find how things had turned against him in the Cities of the Wastes.

He became more extreme than before. His people were to forswear mud-bathing entirely; instead, water would be supplied to every dwelling. They were to keep their casspu orifices covered. Skin oils were forbidden. Greater industry was required. And so on.

But the seeds of dissatisfaction had been well sown by Creezeazs and his followers, and more blood-shedding ensued. Many people returned to their ancestral wallows, leaving the Cities of the Wastes slowly to fall into ruin while the inhabitants fought each other. Everyone regretted this, since there existed a genuine admiration for Manna which nothing could quench.

In particular, his journey among the stars was widely discussed and praised. Much was known, even at that period, about the neighboring celestial bodies known as the Home Cluster, and particularly about the three suns, Welcome White, Saffron Smiler, and Yellow Scowler, around each of which Dapdrof revolved in turn as one esod followed another. These suns, and the other planets in the cluster, were as familiar – and as strange – to the people as the Circumpolar Mountains in Dapdrof's Northern Shunkshukkun.

Whatever woes the Revolution Age had brought, it had brought the chance to investigate these other places. It was a chance the ordinary utod found he wanted.

The Hygienics had control of all star-realm travel. The masses of the unconverted, pilgrimaging from all over the globe to the Cities of the Wastes, found they could par-take in the new exploration of other worlds under one of two conditions. They could become converts to the harsh disciplines of Manna Warun, or they could mine the materials needed for building and fuelling the engines of the arks. Most of them preferred to do the latter.

Mining came easily; had not the utod evolved from little burrowing creatures not unlike the Haprafruf Mud Mole? They dug the ores willingly, and soon the whole process of building star arks became routine, almost as much a folk art as weaving, platting, or Wishing. So in turn travel through the star realms took on something of the same informality, particularly when it was discovered that the Triple Suns and their three near neighbors supported seven other worlds on which life could be lived almost as enjoyably as on Dapdrof.

Then came a time when life indeed was rather pleasant on some of the other worlds: on Buskey, for instance, and Clabshub, where the utodammp system was quickly established. Meanwhile the Hygienics split into rival sects, those that practiced retraction of all limbs, and those that deplored it as immoral.

Finally, the three nuclear Wars of Wise Deportment broke out, and the fair face of the home planet underwent a thoroughly unhygienic bombardment, the severity of which – destroying as it did so many miles of carefully tended forest and swamp land – actually changed climatic conditions for a period of about a century.

The resulting upheavals in the weather, followed by a chain of severe winters, concluded the wars in the most radical of ways, by converting into the carrion stage almost all the surviving Hygienics of whatever persuasion. Manna himself disappeared; his end was never known for sure, although legend had it that a particularly fine ammp, growing in the midst of the ruins of the largest of the Cities of the Wastes, represented the next stage of his existence.

Slowly, the old and more reasonable ways returned.

Helped by utods returning from the other planets, the home population re-established itself. Dams were rebuilt, swamps painstakingly restored, middensteads reintroduced on the traditional patterns, ammps re-planted everywhere. The Cities of the Wastes were left to fall into decay. No-body was interested any more in the ethics of cleanliness. Law and ordure were restored.

Yet at whatever expense it had been acquired, the industrial revolution had borne its fruits, and not all of them were permitted to die. The basic techniques necessary for maintaining star-realm travel passed to the ancient priesthood dedicated to maintaining the happiness of the people. The priesthood simplified practices already smoothed into quasi-ritual by habit and saw that these techniques were handed on from mother to son by mind-suckle, together with the rest of the racial lore.

All that now lay three thousand generations and almost as many esods ago. Through the disciplines of mindsuckle, its outlines remained clear. In Blug Lugug's brains, the memory of the hideous perverted talk and teachings of Manna and other Hygienics was vivid. He prided himself on being the filthiest and healthiest of his generation of priests. And he knew by the absurd phrases of moral condemnation the Cosmopolitan had uttered that the cleanliness inflicted on his old body by the thinlegs was affecting his brains. It was time something was done.

CHAPTER NINE

It was an American sage back in the nineteenth century who coined the slogan since used so successfully on the wrappers of every Happy Hypersleep tablet, "The mass of men live lives of quiet desperation." Thoreau certainly had a point when he observed that anxiety and even misery feed in the breast of those often most concerned with put-ting up a brave show of happiness; yet such is the constitution of human nature that the reverse holds equally true, and under conditions commonly regarded as most likely to create misery, a man may lead a life of quiet happiness.

The gates of St. Alban's prison swung open and emitted the prison bus. It bowled out beneath the aluminum legend over the portal that read "To Understand Is To Forgive", and headed for the region of the metropolis called The Gay Ghetto.

Or so the area was most generally known. Its inhabitants called it The Knackers, or Joburg, or Wonderland, or Sucker City, or indeed any less savory name that occurred to them. The area had been established by a government enlightened enough to realize that some men, while being far from criminal in intent, are incapable of living within the exacting framework of civilization; which is to say that they do not share the goals and incentives of the majority of their fellow beings; which is to say that they see no point in working from ten till four day in and day out for the privilege of maintaining a woman in wed-lock and x or n number of children. This body of men, which numbered geniuses and neurotics in equal proportions (frequently within the same anatomy), was allowed to settle within the Gay Ghetto, which – because it was unsupervised in any way by the forces of law – soon became the nesting ground also of criminals.

Within the ruinous square mile of this human game reserve, a unique society formed; it looked at the monstrous machinery of living that ground on beyond its walls with the same mixture of fear and moral disapproval with which the monstrous machinery regarded it.

The prison taxi halted at the end of a steep brick street. The two released prisoners, Rodney Walthamstone and his ex-cell mate, climbed out. At once the taxi swerved and drove away, its door automatically sliding shut as it went.

Walthamstone looked about him with unease.

The drearily respectable dolls' houses on either side of the street hunched their thin shoulders behind dog-soiled railings, averting their gaze from the strip of waste that began where they left off.

Beyond the waste rose the wall of the Gay Ghetto. Some of the wall was wall; some of it was formed from little old houses into which concrete had been poured until the little old houses were solid.

"Is this it?" Walthamstone asked.

"This is it, Wal. This is freedom. We can live here with-out anybody mucking us about.”

The early sunshine, a snaggle-toothed old trickster, lay its transient gold and broken shadows across the uninviting flank of the Ghetto, of Joburg, of Paradise, of Bums' Berg, of Queer Street, of Floppers.

Tid started towards it, saw that Walthamstone hesitated, grasped his hand, and pulled him along.

"I ought to write to my old Aunt Flo and Hank Quilter and tell 'em what I'm doing," Walthamstone said. He stood between the old life and the new, naturally fearful. Although Tid was his own age, Tid was so much more sure of himself.

"You can think about that later," Tid said.

"There was other blokes on the starship....”

"Like I tell you, Wal, only suckers allow themselves to enlist on spaceships. I got a cousin Jack, he signed on for Charon; he's perched out on that miserable billiard ball, fighting Brazilians. Come on, Wal.”

The grubby hand tightened on the grubby wrist.

"Perhaps I'm being stupid. Perhaps I got all mixed up in jug," Walthamstone said.

"That's what jug is meant for.”

"My poor old aunt. She's always been so kind to me.”

"Don't make me weep. You know I'll be kind to you too.”

Giving up the grueling battle to express himself, Walthamstone moved forward and was led like a lost soul towards the entrance to Avernus. But the ascent to this Avernus was not easy. No portals stood wide. They climbed over rubble and litter towards the solid houses.

One of the houses had a door which creaked open when Tid pulled it. A tongue of sunlight licked in with their untrusting glances. Within, the solid concrete had been chipped into a sort of chimney with steps in the side. Without another word to his friend, Tid began to climb; left with no option, Walthamstone followed. In the gloom on either side of him he saw tiny grottoes, some no bigger than open mouths; and there were cysts and bubbles; and clots and blemishes; all of which had formed in the liquid concrete when it had first been poured down through the rafters and engulfed the house.

The chimney brought them out to an upper window at the back. Tid gave a cheer and turned to help Walthamstone.

They squatted on the window-sill. The ground sloped down from the sill, where it had been piled as an embankment for no other apparent purpose than to grow as fine a crop of cow parsley, tall grass, and elder as you could wish to see.

This wilderness was divided by paths, some of which ran round the upper windows of the solid houses, some of which sloped down into the Ghetto. Already people stirred there, a child of seven ran naked, whooping from door-step to doorstep with a newspaper hat on its head. Ancient facades grew down into the earth, tatty and grand with a patina of old dirt and new sun.

"Me dear old shanty town!" Tid cried. He ran down one of the tracks, a foam of flower about his knees.

Hesitating only a moment, Walthamstone ran down after his lover.

Bruce Ainson assumed his coat with a fine air of desperation, while Enid stood at the other end of the hall, watching him with her hands clasped. He wanted her to start to speak, so that he could say, "Don't say anything!", but she had nothing else to say. He looked sideways at her, and a shaft of compassion pierced through his self-concern.

"Don't worry," he said.

She smiled, made a gesture. He closed the door and was gone.

Outside, he paid ten tubbies into the corner sinker and rose to the local traffic level. Abstractedly, he climbed into a moving chair that skied him up to the non-stop level and racked itself on to one of the robot monobuses. As he sped towards distant London, Bruce dwelt on the scene he had just made with Enid after the news in the paper hit him.

Yes, he had behaved badly. He had behaved badly because he did not, in such a crisis, see the point of behaving well. One was as moral as one could be, as well-intentioned, as well-controlled, as intelligent, as innocent; and then the flood of days brought down with it (from some ghastly unseen headwaters, whence it had been travelling for unguessed time) some vile fetid thing that had to be faced and survived. Why should one behave other than badly before such beastliness?

Now the mood, the shaky exhilaration of the mood, was passing. He had shed it on Enid. He would have to behave well before Mihaly.

But did life have to be quite so vile a draught? Dimly, he recognized one of the drives that had carried him through the years of study necessary to gain him his Master Explorer's certificate. He had hoped to find a world, hiding beyond reach of sight of Earth in the dark light years, a world of beings for whom diurnal existence was not such an encumbrance to the spirit. He wanted to know how it was done.

Now it looked as if he'd never have the chance again.

Reaching the tremendous new Outflank Ring that circled high about outer London, Ainson changed on to a district level and headed for the quarter where Sir Mihaly Pasztor worked. Ten minutes later, he was stalling impatiently before the Director's secretary.

"I doubt if he can see you this morning, Mr. Ainson, since you have no appointment.”

"He has to see me, my dear girl; will you please announce me?”

Pecking doubtfully at the nail of her little finger, the girl disappeared into the inner office. She emerged a minute later, standing aside without speaking to admit Ainson into Mihaly's room. Ainson swept by her with irritation; that was a girl he had always been careful to smile and nod at; her answering show of friendliness had been nothing but pretence.

"I'm sorry to interrupt you when it's obvious you are very busy," he said to the Director. Mihaly did not immediately assure his old friend that it was perfectly all right. He maintained a steady pacing by the window and asked. "What brings you here, Bruce? How's Enid?”

Ignoring the irrelevance of this last question, Ainson said, "I should think you might guess what has brought me here.”

"It would be better if you told me.”

Pulling a newspaper from his pocket, Ainson dropped it on Pasztor's desk.

"You must have seen the paper. This confounded American ship, the Gansas, or whatever it's called, leaves next week to look for the home planet of our ETA's.”

"I hope they will have luck.”

"Don't you realize the absolute disgrace of it? I have not been invited to join the expedition. Every day I expected a word from them. It hasn't come. Surely there must be a mistake?”

"I think it is impossible there should be a mistake in such a matter, Bruce.”

"I see. Then it's a public disgrace." Ainson stood there looking at his friend. Or was he really a friend?

Was it not a gross misuse of the term, just because they had been acquainted for a number of years? He had admired the many sides of Pasztor's character, had admired him for the success of his technidramas, had admired his leader-ship on the First Charon Expedition, had admired him for being a man of action.

Now he saw more deeply; he saw that this was merely a playboy of action, a dramatist's idea of a man of action, an imitation that revealed its spuriousness at last by the calmness with which, from his safe seat at the Exozoo, he watched Ms friend's discomfiture.

"Mihaly, although I am a year older than you, I am not yet ready to accept a safe seat back on Earth; I'm a man of action, and I'm still capable of action. I think I can say without false modesty that they still have need of men like me at the frontiers of the known universe. I was the man who discovered the ETA's, and I haven't for-gotten that, if others have. I should be on the Gansas when she goes into TP next week. You could still pull strings and get me on to her, if you wanted. I ask you – I beg you to do this for me, and swear I will never ask you another favor. I just cannot bear the disgrace of being passed over in a vital moment like this.”

Mihaly pulled a wry face, cupped an elbow and rubbed his chin.

"Would you care for a drink, Bruce?”

"Certainly not. Why do you always insist on offering me one when you know I don't drink?”

"You must excuse me if I have a little one. It is not normally my habit at this early time of morning." As he went over to a pair of small doors set in the wall, he said, "Perhaps you will feel better, or perhaps worse, if I tell you that you are not alone in your disgrace. Here at the Exozoo we have our disappointments. We have not made the progress in communication with these poor ETA's that we had hoped to do.”

"I thought that one of them had suddenly started spouting English?”

"Spouting is right. A series of jumbled phrases with amazingly accurate imitations of the various voices that originally spoke them. I recognized my own voice quite clearly. Of course we have it all on tape. But, unfortunately, this development did not come soon enough to save the axe from falling. I have received word from the Minister for Extra-Terrestrial Affairs that all research with the ETA's is to close down forthwith.”

Unwilling though he was to be diverted from his own concerns, Ainson was startled.

"By the Buzzardian universe! They can't just close it down! This – we've got here the most important thing that has ever happened in the history of man. They – I don't understand. They can't close it down.”

Pasztor poured himself a small whisky and sipped it.

"Unfortunately, the Minister's attitude is understand-able enough. I'm as shocked at this development as you are, Bruce, but I see how it comes about. It is not easy to make the general public or even a minister see that the business of understanding another race – or even deciding how its intelligence is to be measured beside ours – is not something that can be done in a couple of months. Let me put it bluntly, Bruce; you are thought to have been lax, and the suspicion has spread – just a feeling in the winds, no more – that we are similarly at fault. That feeling has made the minister's job a little more easy, that is all.”

"But he cannot stop the work Bodley Temple and the others are doing.”

"I went to see him last evening. He has stopped it. This afternoon the ETA's are being handed over to the Exobiology Department.”

"Exobiology! Why, Mihaly, why? There is a conspiracy!”

"With an optimism I personally regard as unfounded, the Minister reasons like this. Within a couple of months, the Gansas will have located more ETA's – a whole planet full of them, in fact. Many of the basic questions, such as how far advanced the creatures are, will then be answered, and on the basis of those answers a new and much more effective attempt to communicate with them can be launched.”

A sort of shaking took Ainson's body. This confirmed all he had ever suspected about the powers ranged against him. Blindly, he took a lighted mescahale from Pasztor and sucked its fragrance into his lungs. Slowly his vision cleared; he said, "Supposing all this were so; something more must lie behind the minister's move.”

The Director helped himself to another drink.

"I inferred as much myself last evening. The minister gave me a reason which, like it or not, we must accept.”

"What was the reason?”

"The war. We are comfortable here, we are apt to forget this crippling war with Brazil that has dragged on for so long. Brazil have captured Square 503, and it looks as if our casualties have been higher than announced. What interests the government at present more than the possibility of talking with the ETA's is the possibility that they do not experience pain. If there is some substance circulating in their arteries that confers complete analgesia, then the government want to know about it. It is obviously a potential war weapon.

"So, the official reasoning goes, we must find out how these beings tick. We must make the best use of them.”

Ainson rubbed his head. The war! More insanity! It had never entered his mind.

"I knew it would happen! I knew it would! So they are going to cut our two ETA's up," he said. His voice sounded like a creaking door.

"They are going to cut them up in the most refined way.

They are going to sink electrodes into their brains, to see if pain can be induced. They will try a little over-heating here, a little freezing there. In short, they will try to discover if the ETA's freedom from pain really exists: and if it exists, whether it is engendered by a natural in-sensitivity or brought about by an anti-body. I have pro-tested against the whole business, but I might as well have kept quiet. I'm as upset as you are.”

Ainson clenched a fist and shook it vigorously close to his stomach.

"Lattimore is behind all this. I knew he was my enemy directly I saw him! You should never have let -”

"Oh don't be foolish, Bruce! Lattimore has nothing whatever to do with it. Can't you see this is the sort of bloody stupid thing that happens whenever something important is involved. It's the people who have the power rather than the people who have the knowledge who get the ultimate say. Sometimes I really think mankind is a bit mad.”

"They're all mad. Fancy not begging me to go on the Gansas! I discovered these creatures, I know them! The Gansas needs me! You must do what you can, Mihaly, for the sake of an old friend.”

Grimly, Pasztor shook his head.

"I can do nothing for you, I have explained why I my-self am temporarily not very much in favor. You must do what you can for yourself, as we all must. Besides, there is a war on.”

"Now you are using that same excuse! People have all been against me, always. My father was. So's my wife, my son – now you. I thought better of you, Mihaly. It's a public disgrace if I'm not on the Gansas when she hits vacuum, and I don't know what I'll do.”

Mihaly shifted uncomfortably, hugged his whisky glass and stared at the floor.

"You didn't really expect better of me, Bruce. At heart, you know you never expect better of anybody.”

"I certainly shan't in future. You don't wonder a man grows bitter. My God, what really is there to live for!" He stood up, stubbing the end of his mescahale into a disposer. "I can see myself out," he said. In a state approaching elevation, he left the room, forging past the covertly interested secretary. Of course he didn't feel as badly as he led Mihaly, that trumped up little Hungarian, to believe; it would do the fellow good to see that some people had real sufferings, and weren't just poseurs.