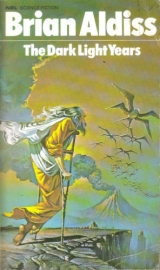

Текст книги "The Dark Light Years"

Автор книги: Brian Aldiss

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 9 страниц)

The Dark Light Years

Brian Aldiss

O dark dark dark. They all go into the dark, The vacant interstellar spaces, the vacant into the vacant, The captains, merchant bankers, eminent men of letters, The generous patrons of art, the statesmen and the rulers....

T. S. ELIOT

CHAPTER ONE

On the ground, new blades of grass sprang up in chlorophyll coats. On the trees, tongues of green protruded from boughs and branches, wrapping them about – soon the place would look like an imbecile Earthchild's attempt to draw Christmas trees – as spring again set spur to the growing things in the southern hemisphere of Dapdrof.

Not that nature was more amiable on Dapdrof than elsewhere. Even as she sent the warmer winds over the southern hemisphere, she was sousing most of the northern in an ice-bearing monsoon.

Propped on G-crutches, old Aylmer Ainson stood at his door, scratching his scalp very leisurely and staring at the budding trees. Even the slenderest outmost twig shook very little, for all that a stiffish breeze blew.

This leaden effect was caused by gravity; twigs, like everything else on Dapdrof. weighed three times as much as they did on Earth. Ainson was long accustomed to the phenomenon. His body had grown round-shouldered and hollow-chested accustoming him to it. His brain had grown a little round-shouldered in the process.

Fortunately he was not afflicted with the craving to re-capture the past that strikes down so many humans even before they reach middle age. The sight of infant green leaves woke in him only the vaguest nostalgia, roused in him only the faintest recollection that his childhood had been passed among foliage more responsive to April's zephyrs – zephyrs, moreover, a hundred light years away. He was free to stand in the doorway and enjoy man's richest luxury, a blank mind.

Idly, he watched Quequo. the female utod, as she trod between her salad beds and under the ammp trees to launch her body into the bolstering mud. The ammp trees were evergreen, unlike the rest of the trees in Ainson's enclosure. Resting in the foliage on the crest of them were big four-winged white birds, which decided to take off as Ainson looked at them, fluttering up like immense butter-flies and splashing their shadows across the house as they passed.

But the house was already splashed with their shadows. Obeying the urge to create a work of art that visited them perhaps only once in a century, Ainson's friends had broken the white of his walls with a scatterbrained scattering of silhouetted wings and bodies, urging upwards. The lively movement of this pattern seemed to make the low-eaved house rise against gravity; but that was appearance only, for this spring found the neoplastic rooftree sagging and the supporting walls considerably buckled at the knees.

This was the fortieth spring Ainson had seen flow across his patch of Dapdrof. Even the ripe stench from the middenstead now savoured only of home. As he breathed it in, his grorg or parasite-eater scratched his head for him; reaching up, Ainson returned the compliment and tickled the lizard-like creature's cranium. He guessed what the grorg really wanted, but at that hour, with only one of the suns up, it was too chilly to join Snok Snok Karn and Quequo Kifful with their grorgs for a wallow in the mire.

"I'm cold standing out here. I am going inside to lie down," he called to Snok Snok in the utodian tongue.

The young utod looked up and extended two of his limbs in a sign of understanding. That was gratifying. Even after forty years* study, Ainson found the utodian language full of conundrums. He had not been sure that he had not said. "The stream is cold and I am going inside to cook it." Catching the right whistling inflected scream was not easy: he had only one sound orifice to Snok Snok's eight. He swung his crutches and went in.

"His speech is growing less distinct than it was," Quequo remarked. "We had difficulty enough teaching him to communicate. He is not an efficient mechanism, this manlegs. You may have noticed that he is moving more slowly than he did.”

"I had noticed it, Mother. He complains about it him-self. Increasingly he mentions this phenomenon he calls pain.”

"It is difficult to exchange ideas with Earthlegs because their vocabularies are so limited and their voice range minimal, but I gather from what he was trying to tell me the other night that if he were a utod he would now be almost a thousand years old.”

"Then we must expect he will soon evolve into the carrion stage.”

"That, I take it. is what the fungus on his skull signified by changing to white.”

This conversation was carried out in the utodian language, while Snok Snok lay back against the huge sym-metrical bulk of his mother and soaked in the glorious ooze. Their grorgs climbed about them, licking and pouncing. The stench, encouraged by the sun's mild shine, was gorgeous. Their droppings, released in the thin mud, supplied valuable oils which seeped into their hides, making them soft.

Snok Snok Karn was already a large utod, a strapping offspring of the dominant species of the lumbering world of Dapdrof. He was in fact adult now, although still neuter: and in his mind's lazy eye he saw himself as a male for the next few decades anyhow. He could change sex when Dapdrof changed suns; for that event, the periodical entropic solar orbital disestablishment. Snok Snok was well prepared.

Most of his lengthy childhood had been taken up with disciplines preparing him for this event. Quequo had been very good on disciplines and on mindsuckle; secluded from the world as the two of them were here with Manlegs Ainson, she had given them all of her massive and maternal concentration.

Languidly, he deretracted a limb, scooped up a mass of slime and mud. and walloped it over his chest Then, re-collecting his manners, he hastily sloshed some of the mixture over his mother's back.

"Mother, do you think Manlegs is preparing for esod?" Snok Snok asked, retracting the limb into the smooth wall of his flank. Manlegs was what they called Aylmer; esod was a convenient way of squeaking about entropic solar orbital disestablishmentism.

"It's hard to tell, the language barrier being what it is," Quequo said, blinking through mud. "We have tried to talk about it, but without much success. I must try again; we must both try. It would be a serious matter for him if he were not prepared – he could be suddenly converted into the carrion stage. But they must have the same sort of thing happening on the Manlegs planet.”

"It won't be long now, Mother, will it?”

When she did not bother to answer, for the grorgs were trotting actively up and down her spine, Snok Snok lay and thought about that time, not far off now, when Dapdrof would leave its present sun, Saffron Smiler, for Yellow Scowler. That would be a hard period, and he would need to be male and fierce and tough. Then eventually would come Welcome White, the happy star, the sun beneath which he had been born (and which accounted for his lazy and sunny good nature); under Welcome White, he could afford to take on the cares and joys of motherhood, and rear and train a son just like himself.

Ah. but life was wonderful when you thought deeply about it. The facts of esod might seem prosaic to some, but to Snok Snok, though he was only a simple country boy (simply reared too, without any notions about joining the priesthood and sailing out into the star-realms), there was a glory about nature.

Even the sun's warmth, that filled his eight-hundred-and-fifty pound bulk, held a poetry incapable of paraphrase. He heaved himself to one side and excreted into the midden, as a small tribute to his mother.

Do to others as you would be dung by.

"Mother, was it because the priesthood had dared to leave the worlds of the Triple Suns that they met the Manlegs Earthmen?”

"You're in a talkative mood this morning. Why don't you go in and talk to Manlegs? You know how his version of what happens in star-realms amuses you.”

"But, Mother, which version is true, his or ours?”

She hesitated before giving him her answer; it was a wretchedly difficult answer, yet only through it lay an understanding of the world of affairs. She said: "Frequently there are several versions of truth.”

He brushed the remark aside.

"But it was the priesthood that went beyond the Triple Suns who first met the Manlegs, wasn't it?”

"Why don't you lie still and ripen up?”

"Didn't you tell me they met on a world called Grud-grodd, only a few years after I was born?”

"Ainson told you that in the first place.”

"It was you who told me that trouble would come from the meeting.

The first encounter between utod and man occurred ten years after the birth of Snok Snok. As Snok Snok said, this encounter was staged on the planet his race called Grudgrodd. Had it happened on a different planet, had different protagonists been involved, the outcome of the whole matter might have been other than it was. Had someone ... but there is little point in embarking on conditionals. There are no "ifs" in history, only in the minds of observers reviewing it, and for all the progress we make, nobody has proved that chance is other than a statistical delusion invented by man. We can only say that events between man and utod fell out in such and such a way.

This narrative will chronicle these events with as little comment as possible, leaving the reader on his honour to remember that what Quequo said applies as much to man as to aliens: truths arrive in as many forms as lies.

Grudgrodd looked tolerable enough to the first utods who inspected it.

Autodian star-realm-ark had landed in a wide valley, inhospitable, rocky, cold, and covered with knee-high thistles for the greater part of its length, but nevertheless closely resembling some of the benighted spots one happened on in the northern hemisphere of Dapdrof. A pair of grorgs were sent out through the hatch, to return in half an hour intact and breathing heavily. Odds were, the place was habitable.

Ceremonial filth was shoveled out on to the ground and the Sacred Cosmopolitan was induced to excrete out of the hatch, in the universal gesture of fertility.

"I think it's a mistake," he said. The utodian for "a mistake" was Grudgrodd (as far as an atonal grunt can be rendered at an into terrestrial script), and from then on the planet was known as Grudgrodd.

Still inclined to protest, the Cosmopolitan stepped out, followed by his three Politans, and the planet was claimed as an appendage of the Triple Suns.

Four priestlings scurried busily about, clearing a circle in the thistles on the edge of the river. With all their six limbs deretracted, they worked swiftly, two of them scooping soil out of the circle, and then allowing the water to trickle in from one side, while the other two trod the resulting mud into a rich rebarbative treacle.

Watching the work abstractedly with his rear eyes, the Cosmopolitan stood on the edge of the growing crater and argued as strongly as ever a utod could on the rights and wrongs of landing on a planet not of the Triple Suns. As strongly as they could, the three Politans argued back.

"The Sacred Feeling is quite clear," said the Cosmopolitan. "As children of the Triple Suns, our defecations must touch no planets unlit by the Triple Suns; there are limits to all things, even fertility." He extended a limb up-wards, where a large mauve globe as big as an ammp fruit peered coldly at them over a bank of cloud. "Is that apology for a sun Saffron Smiler? Do you take it for Welcome White? Can you even mistake it for Yellow Scowler? No, no, my friends, that mauve misery is an alien, and we waste our substance on it.”

The first Politan said, "Every word you say is incontrovertible. But we are not here entirely by option.

We ran into a star-realm turbulence that carried us several thousand orbits off course. This planet just happened to be our nearest haven.”

"As usual you speak only the truth," the Cosmopolitan said. "But we needn't have landed here. A month's flight would have taken us back to the Triple Suns and Dapdrof, or one of her sister planets. It does seem a bit unholy of us.”

"I don't think you need worry too much about that, Cosmopolitan," said the second Politan. He had the heavy grayish green skin of one born while an esod was actually taking place, and was perhaps the easiest going of all the priesthood. "Look at it this way. The Triple Suns round which Dapdrof revolve only form three of the six stars in the Home Ouster. Those six stars possess between them eight worlds capable of supporting life as we know it. After Dapdrof, we count the other seven worlds as equally holy and fit for utodammp, though some of them – Buskey for instance – revolve round one of the three lesser stars of the cluster. So the criterion of what is utodammp-' worthy is not that it has to revolve about one of the Triple Suns. Now we ask -”

But the Cosmopolitan, who was a better speaker than a listener, as befitted a utod in his position, cut his companion short "Let us ask no more, friend. I just observed that it seemed a bit unholy of us. I didn't mean any criticism. But we are setting a precedent." He scratched his grorg judicially.

With great tolerance, the third Politan (whose name was Blue Lugug) said, "I agree with every word you say, Cosmopolitan. But we do not know if we are setting a precedent Our history is so long that it may be that many and many a crew branched out into the star-realm and there, on some far planet, set up a new swamp to the glory of utodammp. Why, if we look around, we may even find utods established here.'1 "You persuade me utterly; in the Revolution Age, such a thing could easily have happened," said the Cosmopolitan, in relief. Stretching out all six of his limbs, he waved them ceremonially to include ground and sky. "I pronounce all this to be land belonging to the Triple Suns. Let defecation commence.”

They were happy. They grew even happier. And who could not be happy? With ease and fertility at hand, they were at home.

The mauve sun disappeared in disgrace, and almost at once a snowball-bright satellite wearing a rakish halo of dust sprang out of the horizon and rose swiftly above them. Used to great changes of temperature, the eight utods did not mind the increasing cold of night. In their newly-built wallow, they wallowed. Their sixteen attendant grorgs wallowed with them, clinging with sucker fingers tenaciously to their hosts when the utods submerged beneath the mud.

Slowly they imbibed the feel of the new world. It lapped at their bodies, yielded up meanings incapable of translation into their terms.

In the sky overhead gleamed the Home Cluster, six stars arranged in the shape – or so the least intellectual of the priestling claimed – of one of the grails that swam the tempestuous seas of Smeksmer.

"We needn't have worried," said the Cosmopolitan happily. "The Triple Suns are still shining on us here. We needn't hurry back at all. Perhaps at the end of the week we'll plant a few ammp seeds and then move homewards.”

"... Or at the end of the week after next," said the third Politan. comfortable in his mud bath.

To complete their contentment, the Cosmopolitan gave them a brief religious address. They lay and listened to the web of bis discourse as it was spun out of his eight orifices. He pointed out how the ammp trees and the utods were dependent upon each other, how the yield of the one depended on the yield of the other. He dwelt on the significances of the word "yield" before going on to point out how both the trees and the utods (both being the manifestations of one spirit) depended on the light yield that poured from whichever of the Triple Suns they moved about. This light was the droppings of the suns, which made it a little absurd as well as miraculous. They should never forget, any of them, that they also partook of the absurd as well as the miraculous. They must never get exalted or puffed up; for were not even their gods formed in the divine shape of a turdling?

The third Politan much enjoyed this monologue. What is most familiar is most reassuring.

He lay with only the tip of one snout showing above the bubbling surface of the mud, and spoke in his submerged voice, through his ockpu orifices. With one of his unsubmerged eyes, he gazed across at the dark bulk of their star-realm-ark, beautifully bulbous and black against the sky. Ah, life was good and rich, even so far away from beloved Dapdrof. Come next esod. he'd really have to change sex and become a mother; he owed it to his line; but even that... well, as he'd often heard his mother say, to a pleasant mind all was pleasant. He thought lovingly of his mother, and leant against her. He was as fond of her as ever since she had changed sex and become a Sacred Cosmopolitan.

Then he squealed through all orifices. Behind the ark, lights were flashing. The third Politan pointed this out to his companions. They all looked where he indicated. Not lights only. A continuous growling noise.

Not only one light Four round sources of light, cutting through the dark, and a fifth light that moved about restlessly, like a fumbling limb. It came to rest on the ark.

"I suggest that a life form is approaching," said one of the priestlings.

As he spoke, they saw more clearly. Heading along the valley towards them were two chunky shapes.

From the chunky shapes came the growling noise. The chunky shapes reached the ark and stopped. The growling noise stopped.

"How interesting! They are larger than we are," said the first Politan.

Smaller shapes were climbing from the two chunky objects. Now the light that had bathed the ark turned its eye on to the wallow. In unison, to avoid being dazzled, the utods moved their vision to a more comfortable radiation band. They saw the smaller shapes – four of them there were, and thin-shaped – line up on the bank.

"If they make their own light, they must be fairly intelligent," said the Cosmopolitan. "Which do you think the life forms are – the two chunky objects with eyes, or the four thin things?”

"Perhaps the thin things are their grorgs." suggested a priestling.

"It would be only polite to get out and see," said the Cosmopolitan. He heaved his bulk up and began to move towards the four figures. His companions rose to follow him. They heard noises coming from the figures on the bank, which were now backing away.

"How delightful!" exclaimed the second Politan, hurrying to get ahead. "I do believe they are trying in their primitive way to communicate!”

"What fortune that we came!" said the third Politan. but the remark was, of course, not aimed at the Cosmopolitan.

"Greetings, creatures!" bellowed two of the priestlings.

And it was at that moment that the creatures on the bank raised Earth-made weapons to their hips and opened fire.

CHAPTER TWO

Captain Bargerone struck a characteristic posture. Which is to say that he stood very still with his hands hanging limply down the seams of his sky blue shorts and rendered his face without expression. It was a form of self-control he had practiced several times on this trip, particularly when confronted by his Master Explorer. "Do you wish me to take what you are saying seriously.

"Ainson?" he asked. "Or are you merely trying to delay take-off?”

Master Explorer Bruce Ainson swallowed; he was a religious man, and he silently summoned the Almighty to help him get the better of this fool who saw nothing beyond his duty.

"The two creatures we captured last night have definitely attempted to communicate with me, sir.

Under space exploration definitions, anything that attempts to communicate with a man must be regarded as at least sub-human until proved otherwise.”

"That is so, Captain Bargerone," Explorer Phipps said, fluttering his eyelashes nervously as he rose to the support of his boss.

"You do not need to assure me of the truth of platitudes, Mr. Phipps." the Captain said. "I merely question what you mean by 'attempt to communicate'. No doubt when you threw the creatures cabbage the act might have been interpreted as an attempt to communicate." "The creatures did not throw me a cabbage, sir," Ainson said. "They stood quietly on the other side of the bars and spoke to me.”

The captain's left eyebrow arched like a foil being tested by a master fencer.

"Spoke. Mr. Ainson? In an Earth language? In Portuguese, or perhaps Swahili?'* "In their own language, Captain Bargerone. A series of whistles, grunts, and squeaks often rising above audible level. Nevertheless, a language – possibly a language vastly more complex than ours.”

"On what do you base that deduction, Mr. Ainson?”

The Master Explorer was not floored by the question, but the lines gathered more thickly about his rough-hewn and sorrowful face.

"On observation. Our men surprised eight of those creatures, sir, and promptly shot six of them. You should have read the patrol report. The other two creatures were so stunned by surprise that they were easily netted and brought back here into the Mariestopes. In the circum-stances, the preoccupation of any form of life would be to seek mercy, or release if possible. In other words, it would supplicate. Unfortunately, up till now we have met no other form of intelligent life in the pocket of the galaxy near Earth; but all human races supplicate in the same way – by using gesture as well as verbal plea. These creatures do not use gesture; their language must be so rich in nuance that they have no need for gesture, even when begging for their lives.”

Captain Bargerone gave an excruciatingly civilized snort "Then you can be sure that they were not begging for their lives. Just what did they do, apart from whining as caged dogs would do?”

"I think you should come down and see them for your-self, sir. It might help you to see things differently.”

"I saw the dirty creatures last night and have no need to see them again. Of course I recognize that they form a valuable discovery; I said as much to the patrol leader. They will be off-loaded at the London Exozoo, Mr. Ainson, as soon as we get back to Earth, and then you can talk to them as much as you wish. But as I said in the first place, and as you know, it is time for us to leave this planet straight away; I can allow you no further time for exploration. Kindly remember this is a private Company ship, not a Corps ship, and we have a timetable to keep to. We've wasted a whole week on this miserable globe with-out finding a living thing larger than a mouse-dropping, and I cannot allow you another twelve hours here.”

Bruce Ainson drew himself up. Behind him, Phipps sketched an unnoticed pastiche of the gesture.

"Then you must leave without me, sir. And without Phipps. Unfortunately, neither of us was on the patrol last night, and it is essential that we investigate the spot where these creatures were captured. You must see that the whole point of the expedition will be lost if we have no idea of their habitat. Knowledge is more important than time-tables.”

"There is a war on, Mr. Ainson, and I have my orders.”

"Then you will have to leave without me, sir. I don't know how the USGN will like that.”

The Captain knew how to give in without appearing beaten.

"We leave in six hours, Mr. Ainson. What you and your subordinate do until then is your affair.”

"Thank you, sir," said Ainson. He gave it as much edge as he dared.

Hurrying from the captain's office, he and Phipps caught a lift down to disembarkation deck and walked down the ramp on to the surface of the planet provisionally label-led 12B .

The men's canteen was still functioning. With sure instinct, the two explorers marched in to find the members of the Exploration Corps who had been involved in the events of the night before. The canteen was of pre-formed reinplast and served the synthetic foods so popular on Earth. At one table sat a stocky young American with a fresh face, a red neck, and a razor-sharp crewcut. His name was Hank Quilter, and the more perceptive of his friends had him marked down as a man who would go far. He sat over a synthwine (made from nothing so vulgar as a grape grown from the coarse soil and ripened by the un-refined elements) and argued, his surly-cheerful face animated as he scorned the viewpoint of Ginger Duffield, the ship's weedy messdeck lawyer.

Ainson broke up the conversation without ceremony. Quilter had led the patrol of the previous night.

Draining his glass, Quilter resignedly fetched a thin youth named Walthamstone who had also been on the patrol, and the four of them walked over to the motor pool – being demolished amid shouting preparatory to take-off – to collect an overlander.

Ainson signed for the vehicle, and they drove off with Walthamstone at the wheel and Phipps distributing weapons. The latter said, "Bargerone hasn't given us much time, Bruce. What do you hope to find?”

"I want to examine the site where the creatures were captured. Of course I would like to find something that would make Bargerone eat humble pie." He caught Phipps' warning glance at the men and said sharply, "Quilter, you were in charge last night. Your trigger-finger was a bit itchy, wasn't it? Did you think you were in the Wild West?”

Quilter turned round to give his superior a look.

"Captain complimented me this morning," was all he said.

Dropping that line of approach, Ainson said, "These beasts may not look intelligent, but if one is sensitive one can feel a certain something about them. They show no panic, nor fear of any kind.”

"Could be as much a sign of stupidity as intelligence." Phipps said.

"Mm, possible, I suppose. All the same. ... Another thing, Gussie, that seems worth pursuing.

Whatever the standing of these creatures may be. they don't fit with the larger animals we've discovered on other planets so far. Oh, I know we've only found a couple of dozen planets harboring any sort of life – dash it, star travel isn't thirty years old yet. But it does seem as if light gravity planets breed light spindly beings and heavy planets breed bulky compact beings. And these critters are exceptions to the rule.”

"I see what you mean. This world has not much more mass than Mars, yet our bag are built like rhinoceroses.”

"They were all wallowing in the mud like rhinos when we found them," Quilter offered. "How could they have any intelligence?”

"You shouldn't have shot them down like that They must be rare, or we'd have spotted some elsewhere on 12B before this.”

"You don't stop to think when you're on the receiving end of a rhino charge," Quilter sulked.

"So I see.”

They rumbled over an unkempt plain in silence. Ainson tried to recapture the happiness he had experienced on first walking across this untrod planet. New planets always renewed his pleasure in life; but such pleasures had been spoiled this voyage – spoiled as usual by other people. He had been mistaken to ship on a Company boat; life on Space Corps boats was more rigid and simple; unfortunately, the Anglo-Brazilian war engaged all Corps ships, keeping them too busy with solar system maneuvers for such peaceful enterprises as exploration. Nevertheless, he did not deserve a captain like Edgar Bargerone.

Pity Bargerone did not blast-off and leave him here by himself, Ainson thought. Away from people, communing -he recollected his father's phrase – communing with nature!

The people would come to 12B. Soon enough it would have, like Earth, its over-population problems.

That was why it was explored: with a view to colonization. Sites for the first communities had been marked out on the other side of the world. In a couple of years, the poor wretches forced by economic necessity to leave all they held dear on Earth would be trans-shipped to 12B (but they would have a pretty and tempting colonial name for it by then: Clementine, or something equally obnoxiously innocuous).

Yes, they'd tackle this unkempt plain with all the pluck of their species, turning it into a heaven of dirt-farming and semi-detacheds. Fertility was the curse of the human race, Ainson thought Too much procreation went on; Earth's teeming loins had to ejaculate once again, ejaculate its unwanted progeny on to the virgin planets that lay awaiting – well, awaiting what else?

Christ, what else? There must be something else, or we should all have stayed in the nice green harmless Pleistocene.

Ainson's rancid thoughts were broken by Waltham-stone's saying, "There's the river. Just round the corner, and then we're there.”

They rounded low banks of gravel from which thorn trees grew. Overhead, a mauve sun gleamed damply through haze at them. It raised a shimmer of reflection from the leaves of a million million thistles, growing silently all the way to the river and on the other side of it as far as the eye wanted to see. Only one landmark: a big blunt odd-shaped thing straight ahead.

"It – " said Phipps and Ainson together. They stared at each other. " – looks like one of the creatures.”

"The mudhole where we caught them is just the other side," Walthamstone said. He bumped the overlander across the thistle bed, braking in the shadow of the looming object, forlorn and strange as a chunk of Liberian carving lying on an Aberdeen mantelshelf.

Toting their rifles, they jumped out and moved forward.

They stood on the edge of the mudhole and surveyed it One side of the circle was sucked by the grey lips of the river. The mud itself was brown and pasty green, streaked liberally with red where five big carcasses took their last wallow in the carefree postures of death. The sixth body gave a heave and turned a head in their direction.

A cloud of flies rose in anger at this disturbance. Quilter brought up his rifle, turning a grim face to Ainson when the latter caught his arm.

"Don't kill it," Ainson said. "It's wounded. It can't harm us.”

"We can't assume that. Let me finish it off.”

"I said not. Quilter. We'll get it into the back of the overlander and take it to the ship; we'd better collect the dead ones too. Then they can be cut up and their anatomy studied. They'd never forgive us on Earth if we lost such an opportunity. You and Walthamstone get the nets out of the lockers and haul the bodies up.”