Текст книги "Killing Patton"

Автор книги: Bill O'Reilly

Жанр:

Военная история

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 12 (всего у книги 25 страниц)

Meanwhile, the SS guards have vanished into the night.

* * *

A fifty-five-year-old German Jew lies in his wooden bunk in the men’s sick barracks at Auschwitz. It is 3:00 p.m. on January 27, 1945. Otto Frank’s daughters are not as lucky as Eva and Miriam Mozes, who will survive Auschwitz and go on with their lives. The Frank family moved to the Netherlands when the rise of Nazism increased anti-Jewish sentiment in Germany. On May 25, 1942, the London Telegraph ran a story with the headline “Germans Murder 700,000 Jews in Poland.” The Times of London was soon reporting, “Over One Million Jews Dead since the War Began,” whereupon the Guardian noted that seven million Jews were now in German custody, and that Eastern Europe was a “vast slaughterhouse of Jews.”

Still, neither Franklin Roosevelt nor Winston Churchill nor Joseph Stalin could effectively confront the atrocities.10 This was not a sinister plot, but rather an awareness that the Germans could not be stopped. The Jews could be saved only by the Allies’ winning the war. In a radio address to the American people on March 29, 1944, President Franklin Roosevelt made clear not only that he knew about Hitler’s determination to kill every Jew in Europe, but also his own plans ultimately to punish all involved.

Frank’s family went into hiding soon after those news reports emerged, moving into a secret apartment in Amsterdam. Life there was squalid and claustrophobic, but at least they were free. For two long years the Franks evaded detection by the Nazis. They were less than a month away from Amsterdam’s liberation by the Allies when the end came.

On August 4, 1944, a secret informant, whose name has never become known, gave away the family’s hiding place to the Gestapo. The Franks were arrested, and within a month Otto; his wife, Edith; and his teenage daughters, Margot and Annelies, arrived at Auschwitz.

As soon as they disembarked from their cattle cars, families were disrupted. Otto Frank has not seen his wife and daughters since September.

As he lies in his bunk this cold January day five months later, Frank does not know if his family members are alive or dead. He does not know that the women in his life, whom he loves so much, have suffered the indignity of being stripped naked within moments of their arrival at Auschwitz, their heads shaved for delousing, and then made to stand in line to have a number tattooed on their left forearms. That number, they were soon told, was their new identity. They no longer had a name.

During their time in Holland, young Annelies—just “Anne” to her family—kept a detailed journal of what their life in hiding was like. She was five feet, four inches tall, with an easy smile and dimples. Her eyes were gray, with just the slightest trace of green. Anne’s wavy hair, before the Germans shaved her skull smooth, was brown and fell to her shoulders.

Incredibly, both girls are still alive as Otto Frank hears ecstatic shouts from outside his barracks. “We’re free,” the prisoners are shouting. “We’re free.”

Soviet soldiers are marching into the camp, taking careful and cautious steps, suspicious of a surprise German attack. They wear winter-white camouflage uniforms and appear out of the snowy mist like apparitions. Eva Mozes cannot see them at first, because they blend into the winter landscape so well.

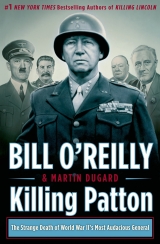

Anne Frank in 1941

But just as she is not sure of what she sees, so the Soviet soldiers are not sure of what they have stumbled upon: corpses everywhere, living skeletons, and the hollow faces of those who are being liberated but who are so close to death that it does not matter. “When I saw the people, it was skin and bones. They had no shoes, and it was freezing. They couldn’t even turn their heads, they stood like dead people,” the first Russian officer into the camp will later remember. “I told them, ‘The Russian army liberates you!’ They couldn’t understand. Some few who could touched our arms and said, ‘Is it true? Is it real?’”

The Soviet soldiers move from barracks to barracks, shocked at what they see.

“When I opened the barrack, I saw blood, dead people, and in between them, women still alive and naked,” Russian officer Anatoly Shapiro will remember. “It stank; you couldn’t stay a second. No one took the dead to a grave. It was unbelievable. The soldiers from my battalion asked me, ‘Let us go. We can’t stay. This is unbelievable.’”

Despite their brutal reputations, the Soviet soldiers are kind to the prisoners, who stare back at them “with gratitude in their eyes.” But the Russians have seen so much in this time of war that many are numb to the horrors before them. “I had seen towns being destroyed. I had seen the destruction of villages. I had seen the suffering of our own people. I had seen small children maimed—there was not one village that had not experienced this horror, this tragedy, these sufferings,” one Soviet soldier will note wearily.

And yet the Soviets see that Auschwitz is different. “We ran up to them,” Eva Mozes and her sister, Miriam, will later recall. “They gave us hugs, cookies, and chocolates. Being so alone, a hug meant more than anybody could imagine, because that replaced the human worth we were starving for. We were not only starved for worth, we were starved for human kindness, and the Soviet Army did provide some of that.”

Eva Mozes has kept the promise that she made to herself. Neither her corpse nor that of her sister will ever litter the filthy floor of a barracks lavatory.

* * *

As Otto Frank rises from his sickbed to celebrate his newfound freedom, his thoughts immediately turn to finding his family.

But he will never find them. Instead, in the weeks and months and years to come, he will discover threads of their travels, which will allow him to piece together the horrible ways in which they died.

Otto Frank’s beloved wife, Edith, died of starvation, right here at Auschwitz. His daughters were transferred to Bergen-Belsen, in northern Germany. Margot Frank died soon afterward.

Her sister, Anne, had just five weeks to live. She would die bald and covered with insect bites, her emaciated body finally done in by a typhoid outbreak that would kill seventeen thousand inmates at Bergen-Belsen.

She was just fifteen years old.11

* * *

“Judaism,” Adolf Hitler tells the German people on the twelfth anniversary of the day he became chancellor, “began systematically to undermine our nation from within.”

Hitler’s physical health has further deteriorated. His hands shake. His eyes water. He is now taking twice-a-day injections of methamphetamine so he can function. And yet he and Eva Braun carry on the charade that the war can still be won. But Hitler’s location inside the bombed-out ruins of Berlin tells the true story. It has been two weeks since his personal train slunk into the once-proud capital of Germany in the dead of night. The curtains were drawn as a precaution against Allied bombing—though that is really more a habit than anything else. The Luftwaffe has been destroyed. American and British bombers are free to attack Berlin in broad daylight—which they do most days by nine in the morning, as the city’s embattled residents hurry off to work.

There will be no stopping the Allies on the Western Front; of that, Hitler is certain. To the east, where the Russian superiority is eleven soldiers for every Wehrmacht fighter, the situation is even worse.

On this very day, January 30, 1945, Hitler’s minister of armaments, Albert Speer, has sent Hitler a memo informing the Führer that the war is lost. Germany does not have the industrial capacity to churn out the tanks, planes, submarines, and bombs necessary to defeat the Allies. Nor does it have the manpower.

Nevertheless, Hitler has no plans to surrender. Nazi scientists are currently working on a new type of weapon known as an atomic bomb.12 Once it is capable of being detonated, he can use it to wipe the Allied armies off the map. “On this day I do not want to leave any doubt about something else. Against an entire hostile world I once chose my road, according to my inner call, and strode it, as an unknown and nameless man, to final success; often they reported I was dead and always they wished I were, but in the end I remained victor in spite of all. My life today is with an equal exclusiveness determined by the duties incumbent on me.”

Hitler now makes his home in central Berlin, on the Wilhelmstrasse. He lives underground, in an elaborate bunker.13 The blond-haired, blue-eyed Eva Braun still tends to him, though she often spends time outside the bunker and does not sleep there most nights. She remains calm, believing that Hitler’s cruel genius can once again win the day. Living in an underground bunker is just one more precaution that is necessary in a time of war. Adding to the air of normalcy is that Hitler’s beloved German shepherd, Blondi, and her new puppies make their home in the bunker as well.

Even though he fears that a direct hit from an Allied bomb will kill him, Adolf Hitler ultimately believes he will be saved. “However grave the crisis may be at the moment, it will, despite everything, finally be mastered by our unalterable will, by our readiness for sacrifice and by our abilities. We shall overcome this calamity, too, and this fight, too, will not be won by central Asia but by Europe; and at its head will be the nation that has represented Europe against the East for 1,500 years and shall represent it for all times: our Greater German Reich, the German nation.”

Adolf Hitler has ninety days to live. He will never leave Berlin again.

15

A RURAL ROAD IN POLAND

SPRING 1945

NIGHT

Helena Citrónóva is on a mission.

She is a twenty-five-year-old Slovakian Jew who survived Auschwitz, thanks to her beauty, elegant singing voice, and guile. Helena was among the first women deported from Slovakia, on March 25, 1942. The women in the group were all between eighteen and twenty-two years old, and chosen for their youth. Their train chugged out of Poprad station at eight o’clock on that fateful spring evening, climbing slowly over the volcanic Vihorlat Mountains in the night to arrive in Auschwitz the following morning.

Now Helena and her older sister, Rozinka, bed down in a barn, hoping for rest after a long day on the road. They are hungry and thirsty, but for now there is a roof over their heads and they are warm. Yet there is no safety in a war zone.

The Soviet liberation of Auschwitz has come at a time when the Red Army’s immediate focus is on capturing Berlin. Its soldiers have little interest in providing care for the thousands of women and children the Nazis have left to die.

Helena and Rozinka are walking hundreds of miles to their home in the central Slovakian town of Humenné. Like so many others, they are marching away from the Germans as the Soviets are racing toward them. Each night, the barns and hedgerows of Germany and southern Poland are filled with refugees hoping for a few hours’ sleep before they rise again to continue their journeys. Many have vague hopes of temporarily resettling in a major city such as Budapest. Not Helena and Rozinka Citrónóva. They have endured Auschwitz and deportment to another camp just a week before the Russians liberated Birkenau. Throughout their long captivity they have imagined the day they will once again walk through the front door and into the warmth and comfort of the house in Humenné where they were raised.

Now, as they try to sleep in the hay, the two women hear the soft breathing of their exhausted fellow travelers. Sleeping so close to strangers does not bother the sisters. They slept four to a cramped bunk while in Auschwitz. Sharing a stable feels far less claustrophobic.

Rozinka is the plainer of the two women. She is ten years older than Helena, but it is the loss of her two children in the gas chambers that has aged her. However, if not for Helena, she would not be alive at all.

Within Auschwitz-Birkenau there was a building where the clothing, suitcases, and other personal belongings of prisoners were taken after they’d been stripped upon arrival at the train platform. It was known as Canada. Laborers were allowed to steal clothing or food clandestinely as they searched through the piles of belongings for the gold, cash, and other valuables that would be sent back to Berlin to fund the Nazi war machine.

Helena was not originally assigned to Canada, but she quickly grasped the reality that her life would be easier if she could secure a spot in the sorting house. When a woman she knew who worked in Canada died, Helena switched uniforms with her and took her place the next day.

She was instantly found out. The kapo (as the Jewish informants who supervised their fellow prisoners were known) made it clear that she would be punished. This was no idle threat. The kapos could be incredibly harsh to their fellow Jews. In one instance, an Auschwitz kapo beat an inmate over the head with a shovel. Then, as the man fell to the ground, the kapo shoved the blade down into his throat, breaking his neck. He then pried the dead man’s mouth open and hammered out his gold teeth.

So Helena had good reason to be scared that some sort of severe punishment awaited her.

Then, before the kapo could betray her, fate intervened. The date was March 21, 1944. Helena had been a prisoner in Auschwitz for two years. That day was also, coincidentally, the birthday of an SS guard named Franz Wunsch. Known to be an avowed “Jew hater,” the twenty-two-year-old Wunsch was in charge of the Canada work detail. That day, he took the liberty of stopping the sorting process for a short time, and asked if anyone would sing for him. Recognizing the opportunity for what it was, Helena volunteered. Her voice soon wafted through the detritus of the sorting house, a stunning contrast to the sadness of ransacking dead people’s clothing.

Wunsch was transfixed.

He immediately fell for the raven-haired Helena. Not long after, he took the bold risk of handing her a love note. Relations between guards and Jews were strictly forbidden, although they were a common occurrence. The guards took the risk for the sex. The prisoners took the gamble to save their lives.

But Helena was not interested—not at first. “He threw me a note,” she will later remember. “I destroyed it right there and then. But I could see the word ‘love’—‘I fell in love with you.’”

Helena was appalled. “I thought I’d rather be dead than be involved with an SS man. For a long time afterward, there was just hatred. I couldn’t even look at him.”

But the smitten Wunsch was persistent. Every day, he would seek her out among the women at work in Canada. He would sneak her cookies, and took special interest in her welfare: the SS guard was trying to buy his way into her heart.

Then an incredible thing happened. Helena’s sister, Rozinka, along with her two children, arrived at Auschwitz via a train from Slovakia. Wunsch noticed them.

“Tell me quickly what your sister’s name is before I’m too late,” he demanded of Helena.

“You won’t be able to,” she replied coolly. “She has two young children.”

Wunsch was taken aback. “Children can’t live here.”

Finally, Helena gave him her sister’s name. Wunsch then raced to the crematorium and, for show, beat Rozinka in front of her children, explaining to his fellow SS guards that she had disobeyed an order to work in Canada. The guards looked the other way as Wunsch dragged her off, leaving Rozinka’s young daughter and infant son to die. Harsh as it was, Wunsch saved the woman’s life.

Helena, however, now owed a debt to the SS guard.

“In the end, I loved him,” Helena will recall of the affair that began that day. “But it could not be.”

Franz Wunsch was sent to the Russian front as the war came to an end, along with many of his fellow guards. His last act of kindness was making sure that Helena and Rozinka each had a pair of warm fur-lined boots to help them survive the winter.

When the soldiers of the Soviet Sixtieth Army entered the camp on January 27, they were particularly taken with the plunder inside the building known as Canada. Almost a million articles of women’s clothing and half as many men’s garments still waited to be sorted.

But that job no longer fell to Helena and Rozinka. Their nightmare was over—at least for the moment. Working in Canada meant they had enjoyed better rations and regular access to water. They had not been beaten, and were extremely healthy compared to so many others in the camp. So they began walking home to Slovakia, eager to put as much distance between themselves and Auschwitz as possible.

But isolated country roads are never completely safe, even in peacetime. Now, as Helena and Rozinka sleep in the barn, their nightmares begin again. Soviet soldiers reeking of alcohol suddenly invade their small sanctuary. It is not one Red Army soldier, or even two, but an entire gang. They are thin from their long days of marching. Their clothes are threadbare. One by one, the women sleeping in the barn are wrestled to the ground if they try to run and then brutally raped, sometimes twice. “They were drunk—totally drunk,” Helena later remembers. “They were wild animals.”

As this goes on, Helena disguises her looks, messing her hair and covering her face in grime to make herself appear unattractive. The plain and matronly Rozinka helps shield her sister from the soldiers by pretending to be her mother. Some of those attacked show the Russian shoulders their camp tattoos, and cry out that they are Jewish, hoping it will make the Russians see them as undesirable. The soldiers’ reply, delivered in terse German from those who have picked up a smattering of the language, is coarse: “Frau ist Frau”—“A woman is a woman.”

Somehow Helena and Rozinka escape being raped. However, they must silently listen to the screams of those women being violated, and then the heart-wrenching silence when the act is completed.

The Russian soldiers are not satisfied with mere sexual conquest. They are animals, biting away chunks of women’s breasts and cheeks and savagely mauling their genitals. Many strangle their victims after the act, silencing them forever. Perhaps they prefer murder to the personal shame of their victims glaring at them in hatred.

“I didn’t want to see because I couldn’t help them,” Helena remembers. “I was afraid they would rape my sister and me. No matter where we hid, they found our hiding places and raped some of my girlfriends.”

Russian soldiers raped millions of women during the course of the war.1 A large proportion of these women will contract venereal disease from their attackers. Some of them will commit suicide afterward. Others will become pregnant but refuse to carry a rapist’s baby to term and will find a way to abort the fetus. Many of those who give birth to these children of rape—Russenbabies, as they will be known—will abandon them. For some women, such as those in the barn, the liberation of Auschwitz was not the end of their suffering, but the beginning of a new kind of suffering.

“They did horrible things to them,” Helena will recount decades later, from her new home in the Jewish nation of Israel, the image of kicking, biting, and clawing at a young Soviet officer to prevent herself from becoming a victim of rape still clear in her head.

“Right up to the last minute we couldn’t believe that we were still meant to survive.”

* * *

Many Auschwitz survivors find there is no shelter, even when they make it back to their hometowns. All throughout Eastern Europe, Joseph Stalin and the Russian military machine have taken advantage of the mass Nazi deportations of Jews to steal homes and farms and give them to the Russian people. This is just the start of a massive forced migration that will see millions of non-Soviets in Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria, and Poland forced out of their homes. They will be left to resettle in the ruins of the Nazi occupation, in lands that will be without industry, farming, or infrastructure.

Like Helena and Rozinka Citrónóva, Linda Libusha is a Slovak who has survived Auschwitz. As she walks the streets of her beloved hometown of Stropkov, from where she was arrested and led away in March 1942, she believes the nightmare of the camps may be finally behind her.

But Linda doesn’t recognize anyone during her stroll down the main street. It’s as if everyone she ever knew has vanished. When she knocks at the door of the house in which she grew up, it is answered by someone she has never seen before, a heavyset man with a red Russian face. Over his shoulder she can see the same familiar rooms and hallways where she once played as a child—and where this foreigner now makes his home.

The Russian takes no pity on the death camp survivor.

“Go back where you came from,” he says, slamming the door in her face.