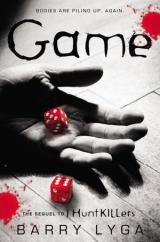

Текст книги "Game"

Автор книги: Barry Lyga

Соавторы: Barry Lyga

Жанры:

Триллеры

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 9 (всего у книги 25 страниц)

CHAPTER 22

Connie sat on her bed in a lotus position, legs folded over each other, her wrists resting lightly on her knees, eyes closed. There was a single yoga studio in Lobo’s Nod, and Connie didn’t like the woman who led classes there, so after three she’d bailed. Ginny Davis—poor, dead Ginny—had lent Connie a set of yoga DVDs that looked like they’d come from the ancient 1990s. Then again, yoga was an ancient practice, so maybe that was appropriate.

At any rate, she’d learned a lot from those DVDs, techniques she’d used over the past year to relax herself, especially before a performance. But right now, she was having trouble centering herself. She couldn’t get those deep, cleansing yoga breaths she craved.

Images of Jazz flashed through what was supposed to be a clear and passive mind. Jazz in the hotel room. Next to her in bed. On the floor. Jazz at the airport, with her father…

It was no good. She couldn’t relax. She blew out a frustrated breath and opened her eyes.

“Whiz!” she yelped. She must have been more relaxed than she’d imagined. Or at least more distracted—her younger brother had managed to sneak into her room without her hearing the door open.

“You are in so much trouble!” Whiz said, with something like awe in his voice. He wasn’t even taking delight in his older sister’s travails. He was just impressed at the sheer level of trouble, like a man reaching a mountaintop only to see a taller peak in the near distance. “I didn’t think you could get in this much trouble!”

“I know,” Connie said, pretending not to care. She couldn’t keep up the pretense for long. “Uh, exactly what have you heard? What did they say while I was gone?”

Whiz scampered over to her bed and plopped down next to her. “Dad was cussing.”

Ouch. Never a good sign. As if Connie needed to know, Whiz proceeded to reel off the exact words Dad had used. Connie blinked. She hadn’t even known Whiz knew some of those words.

“What about Mom?”

“She cried. Not much. Just a little.”

Connie deflated. Her father’s anger was one thing. Bringing her mother to tears was another. She didn’t know why, but those tears touched her more deeply than her father’s anger ever could. In a way, she was glad her parents didn’t know this. Such knowledge would make controlling her almost trivially easy: Don’t do X, Y, or Z, Connie—you’ll make your mother cry.

“Was it worth it?” Whiz wanted to know. “You’re gonna be grounded until, like, you’re eighty years old.”

“They can’t ground me that long,” Connie said.

“But was it worth it? You know”—and here Whiz looked around as if under surveillance and dropped his voice to a near whisper—“S-E-X?”

As much as she wanted to drop-kick Whiz into a garbage chute most days, Connie had to admit she loved the little snot monster, who was simultaneously too grown-up and too childlike. After busting out a plethora of Dad’s four-letter words, he still felt the need to spell out sex.

“We didn’t have S-E-X,” she informed him. “Not that it’s any of your business.”

“Well, that’s good. ’Cause Mom was really worried about that.”

“Dad wasn’t?”

“Dad was…” Whiz hesitated. “Never mind.”

“Come on. Tell me.”

Whiz shook his head defiantly.

“God, it’s more of his black/white crap, isn’t it? It’s not the nineteen-sixties. It’s not like when his parents were growing up or even when he was growing up. It’s—”

“That’s not it,” Whiz said quietly.

“What’s not it?”

“The black-and-white thing. The racial stuff.”

Connie stared at her kid brother, searching his expression for signs of one of his pranks or tricks. But he was utterly solemn, totally serious.

“What do you mean? Ever since I started dating Jazz, it’s been ‘white men this’ and ‘black women that,’ and ‘Sally Hemmings’ and—”

Whiz shook his head. “He doesn’t care. He said, ‘She can date a whole platoon of white boys, just not that one.’ ”

Connie set her jaw. She knew what was coming next. “How do you know this?”

Whiz rolled his eyes. “Jeez, Connie. I listen to them at night through the air-conditioning vents. Don’t you?”

Actually… no.

“It’s the serial-killer thing.”

Well, of course it was the serial-killer thing. Her father didn’t trust Jazz. So typical. No matter how much Jazz had proven himself—

“And,” Whiz went on, “he told Mom that the idea of you getting hurt scares him so much that he can’t even talk to you about it. And all the race stuff is just the only way he can think of to keep you guys apart without thinking about you…”

Without thinking of me raped, tortured, mutilated, and murdered by my own boyfriend. Ah, crap. She couldn’t find it in her heart to stay angry at her dad. Not anymore.

“Jesus, Whiz. Talking to you is better than yoga sometimes.”

“Don’t take—”

“—the Lord’s name in vain. I know. Sorry.”

“It isn’t gonna happen, is it?” Whiz asked.

“What’s that?”

Whiz swallowed. “Jazz isn’t gonna hurt you, is he?”

Aw, man… As big of a pain in the butt as her little brother could be, she knew he loved her in that stunted way little brothers have. It killed her to see the conflicted pain in his eyes as he asked. She saw more than merely her brother’s concern; she saw Dad’s fear reflected there, too. All her life, her father had been so powerful, loomed so large, that she’d never been able to imagine him afraid of anything. Not even Jazz. Not even something…

“No one’s gonna hurt me,” she told Whiz. Seized by a rare impulse, she hugged him to her, pleasantly surprised that he didn’t pull away.

She kissed him on the exact center of the top of his head and said it again, this time louder, loud enough to convince herself, too.

CHAPTER 23

For the first time in recent memory, Jazz had the run of the house. After breakfast, Gramma had fallen into one of her periodic obsessions with Grampa’s grave. Sometimes she believed that he’d risen from the grave—“Like Jesus and Bugs Bunny!”—and could only be persuaded otherwise by a trip to the cemetery. Jazz hated those days; Gramma would spend hours crawling around the headstone, inspecting the dirt and individual blades of grass for some sort of perfidy. It was a lousy way to spend a day.

But Aunt Samantha cheerfully volunteered to take Gramma, meaning that Jazz was alone in the house without having to worry about his grandmother. He almost didn’t know how to act. It was so quiet—true quiet, without the foreboding of a potential Gramma eruption lurking. Maybe I should call Connie and we can fool around in my bedroom for a change.

It was an automatic thought, and it made him pensive almost immediately. He should call Connie. But what could he say to her? Especially after the way he’d treated her father at the airport. Combine that with the hotel-room fiasco and he’d be surprised if she ever wanted to speak to him again.

Oh, you could make her talk to you….

No. Shut up, Billy. Not Connie. I don’t do that to Connie.

He meandered around the house, straightening things here and there. Inspired, he started throwing away some of the old junk that his grandmother had accumulated over the years. The serial-killer pack-rat tendency ran strong in the Dent genetics, and Gramma would never tolerate Jazz throwing things away while she was around. But with her gone for the day, he could do some cleaning and she’d be none the wiser. It’s not like she was lucid enough to memorize her piles of crap.

He thought about Connie as he roamed the house with a garbage bag. He’d been unfair to her, he knew, but how to fix that unfairness was beyond him. He relived the night in the hotel room, running it through his damnably perfect memory over and over. Waking from the dream. Pressed deliciously and deliriously against Connie. Her turning to him, eyes wide and full and dark. Reaching for each other. Familiar touches gone explosively unfamiliar, explosively craved.

And then… pushing her away, falling backward onto the floor, lust twisted to panic, to fear.

Yeah. How could he fix that? How could he erase in Connie’s mind the memory of her boyfriend fleeing from her in terror?

He hauled the garbage outside and set it by the mailbox for pickup, then returned to the house, where he wheeled his suitcase into the spare room. He didn’t blame Samantha for not wanting to sleep here. The room had lain unused for close to two decades, its surfaces gray and textured with dust. More than that, though, the room seemed to vibrate, ever so slightly out of sync with the rest of the house, the rest of the universe, really. As though something fundamental and primitive and crucial had broken here, and never been patched.

Billy’s room. Billy’s bed. Jazz didn’t have to wonder what Billy had dreamed and fantasized, lying awake at night. He knew all too well—Billy had written his fantasies in the blood and screams of innocents from Nevada to Pennsylvania, from Texas to South Dakota. No secrets remained.

He dusted a bit, then unpacked. He needed clean clothes, so he went across the hall to his room. True to her word, Samantha had hung a sheet over the wall of Dear Old Dad’s victims. Jazz found himself liking his aunt more and more. Wouldn’t most people seeing them for the first time—most normal people—have taken down the pictures? Connie thought they were morbid. G. William thought they were a disturbing tie to the past. Howie thought they were a buzzkill.

Gramma thought they were Santa’s elves.

He fired up his computer and checked his e-mail. Other than the usual spam and porn links from Howie (delete, delete, delete…), there was nothing, which meant that no one had figured out this e-mail address yet. Good.

On the desk lay two sheets of paper. Photocopies of evidence from the sheriff’s office. The first one was the letter Billy had left at Melissa Hoover’s house:

Dear Jasper,

I can’t begin to tell you what a pleasure it was to see you at Wammaket. You’ve grown into such a strong and powerful young man. I am so proud of what you will accomplish in this life. I already know you are destined for great things. I dream of the things we’ll do together. Someday.

For now, though, I have to leave you with this. Never let it be said your old man doesn’t know how to repay a debt.

Love,

Dear Old Dad

PS Maybe one of these days we’ll get together and talk about what you did to your mother.

The PS still stabbed at him, cored him. When Jazz had point-blank asked Billy “Did you make me kill my mother?” Billy had just laughed. Later, he had said, “You’re a killer. You just ain’t killed no one yet.”

Which statement was true? Was it all Billy screwing with his mind?

Well, of course it was Billy screwing with his mind. That’s what Billy did. Dear Old Dad had a PhD in mind screwing. The question was, was it just Billy screwing with his mind?

He shook his head and actually said “Stop it!” out loud to himself in his strongest voice. What had happened? How had Janice Dent died? By Billy’s hand, or by her son’s?

That’ll be the first thing I do. The next time I see him, the first thing I do will be to ask him that.

And the second thing?

He remembered Special Agent Morales leaning toward him. She wore no perfume. Her face was smooth and unblemished by makeup, and her grin had revealed big, strong teeth. “You want to do more than find him, don’t you? You want to kill him,” she’d said. “Well, I can help with that.”

The second thing—he would figure that out when the time came.

The other piece of paper was the letter found on the Impressionist. It was two pages long, but the sheriff’s department had reduced it to fit both pages on one sheet. Handwritten in a careful, neat, and unfamiliar hand. Most of the letter was a listing of the major characteristics of Billy Dent’s first victims, with notations as to possible doppelgängers for the Impressionist to use in his harrowing of Lobo’s Nod. But there was an appendix at the end, one that still mystified Jazz:

UNDER NO CIRCUMSTANCES ARE YOU TO

GO NEAR THE DENT BOY.

LEAVE HIM ALONE.

YOU ARE NOT TO ENGAGE HIM.

JASPER DENT IS OFF-LIMITS.

He stared at the letter for a while, willing the letters to rearrange themselves into something that made more sense, then gave up, grabbed some clean clothes and the letters, and headed to his temporary quarters. He figured he’d delayed the inevitable long enough.

Sitting on the floor, his back against his father’s childhood bed, Jazz called Connie.

“Hey,” she said.

“Hey,” he said back.

Neither of them said anything. Jazz ran through his options. Pretend nothing had happened? Apologize immediately? The nuclear option: break up. He’d written and rewritten the speech in his head a million times: I know you love me and I love you, but I’m broken, Connie. I’m defective. I’m the toy you got for Christmas that’s missing pieces, and even if it was complete, no one bought the batteries to go with it.

“Before we talk about anything else, I need to say I’m sorry,” Connie said.

“Excuse me?”

“I shouldn’t have pushed you. I know you have… issues with sex. I get it. And, I mean, don’t get me wrong. I totally think we’re ready, but I went about it wrong. It wasn’t cool. So I’m sorry.”

Jazz closed his eyes and thumped the back of his head against the bed. “Con… it’s not… you didn’t do anything wrong. It’s me. It was me. And then with your dad… I just…”

“I know. And we’ll talk about that in—look, you don’t have to… In New York. I just thought that with me, it might be okay. It might be safe. For you.”

He sat upright. “What do you mean? What do you mean by that?”

“Well, I know that your dad never… never prospected any African Americans. Right?”

Jazz’s heart thrummed. What?

“And I always figured that that maybe meant that I wouldn’t… that I couldn’t…” She blew into the phone, exasperated. “I know what you’re worried about. You’re worried that he somehow, like, programmed you to be a serial killer. And that there’s all this crazy lurking under the surface—”

“It’s not just under the surface,” he said seriously.

“I know. But anyway, there’s this stuff buried in you, and you’re afraid it’ll erupt if you have sex. Like, sex is the trigger, right? But Billy never killed any black women. It’s like he just skipped over us. Almost deliberately. Like we don’t exist to him. So I thought maybe that made me safe for you.” She paused. “Didn’t you ever think that?”

Jazz held back a laugh of commingled relief and horror. His big secret! His hidden fear! That Connie would someday find out why he’d first dated her. How long had he been terrified of telling her this, only to learn that not only did she know but she was okay with it and thought it was a good idea.

“I don’t know what to say,” he admitted. “I was just sitting here thinking how I needed to apologize to you—”

“For what? For freaking out?” She said it like it was no big deal.

“For that. For the way I freaked out. And now, I guess, for the way we first started dating. Which seems pretty racist, now that I think about it.”

Connie laughed. “Jazz, if you liked—I don’t know—blond girls or girls with big boobs—”

“Your boobs are pretty big.”

“Anyway. If you had a thing for one of those girls and saw her across a crowded room and went and introduced yourself, would that be a bad thing?”

“I don’t know.”

“Well, I do—the answer is no. So, in my case, you saw a really foxy-looking black girl across a crowded room—”

“It was the Coff-E-Shop and it was close to closing, so no one was there.”

“—and you were like, ‘I like black girls, so I’m going to introduce myself.’ No big deal.”

“Yeah, but what if the reason I like black girls is because they’re, you’re, safe—”

“So what? Who knows why anyone likes what they like? Guys who are obsessed with, like, redheads. Why? Because they’re rare? Because they had a redheaded babysitter? Because they watched too many Emma Stone movies? Beats me. Who cares? I mean, why do I like white boys?”

“I’m the only white boy you’ve ever dated.”

“And I’m the only black girl you’ve ever dated. So there.”

“So, we’re good?”

“We’re beyond good.”

“Is your dad gonna come at me with a shotgun the next time I come over?”

“Probably.” She waited for a moment. “You went too far, you know. At the airport.”

“I know.”

“You crossed the line.”

“I know.”

“It’s one thing to mess with a teacher’s head to get out of detention or to charm that girl at the police station to get you some file you shouldn’t have, but—”

“I know.”

“—this is my dad, Jazz. He’s my father. And you were, like, like, waving a cape in front of a bull.”

“It was totally wrong.”

“And you know what they do to the bulls, right? And that’s how you were treating my dad.”

“I’m sorry. I really am.” Nah, Billy whispered, you ain’t sorry. You just know sayin’ it gets you what you want.

Jazz shook Billy away. He was sorry.

He was, like, 99 percent sure he was really sorry.

“I shouldn’t have done that,” he said. “I’ll apologize to your dad right now.”

Maybe 98 percent.

“That is not a good idea. He’s still on fire. He’s so pissed it’s ridiculous. He just now stopped lecturing me. If you’d called five minutes ago, he would have grabbed the phone and you’d be talking to him instead.”

Ouch.

“But anyway,” she went on, “every couple has their thing, you know? My dad doesn’t like you. And your grandmother thinks I’m the spawn of Satan. We’ll deal.”

“What about…” He didn’t even want to bring it up, but he had to. It was in the open now. “What about sex?”

“Yes, please,” Connie deadpanned.

He laughed. “Seriously. Come on.”

“We’ll take it slow.”

“We’ve been taking it slow. Because of me. You know it’s true, Con. Any other guy would have been all over you after a week. We’ve been together for almost a year.”

“Maybe those guys would have been all over me, but they wouldn’t have gotten anywhere. And you wouldn’t have gotten anywhere, either. Not that soon. I wasn’t ready. Not then. Now I am. Any man worth having will wait for his woman to be ready. How can I not return the favor?”

And that was when Jazz knew Connie was more and better than he deserved.

“I’ll just have to get by thinking about you while I’m in the shower,” she went on. “It’s gotten me this far.”

Jazz groaned. “You just had to put that image in my head, didn’t you?”

“It’s a pretty great image,” she admitted. “All that lather and soapy bubbles making me slick and shiny.” Her voice dropped, low and sweet.

Jazz adjusted uncomfortably. “I surrender. We need to change the subject. You’re killing me.”

He could almost hear Connie’s delicious smile over the phone. “What are we supposed to talk about?”

“I don’t know. Tell me what you were doing while I was with the cops yesterday.”

“Oh, yeah. Right.” She quickly filled him in on her mini-tour of some of the murder sites.

“Crime scenes,” he corrected her. “It’s possible they were murdered elsewhere and dumped there.”

“Right, right. Anyway, there was this graffito—”

“Graffito?”

“It’s the singular of graffiti.”

“Now you’re just messing with me.”

“I swear to God. Graffiti is plural. It’s like data and datum.”

“No one says ‘datum.’ ”

“People who speak properly do,” Connie sniffed. “Anyway, someone had painted Ugly J.”

“Ugly J? Why did you even notice that?”

She explained how it had stood out. “So someone went back afterward and left that tag,” Jazz mused.

“Maybe the killer? They go back to the scene, right?”

“Sometimes. Not always. It’s just as likely it’s some smart-ass tagging crime scenes. Some kid’s idea of a sick joke.”

“I don’t know. It wasn’t stylized or artistic. Like, most taggers have a style. A little finesse. They want it to stand out, to be noticed. But this was just there. It was like doing your homework in Arial or Times New Roman. And before you asked: I already Googled Ugly J. Didn’t find anything.”

“It’s probably some New York thing.”

“I love the way you say ‘New York’ with such contempt,” Connie said, laughing. “You were there, what, thirty-six hours? And you already hate the place.”

“Can we talk about something else?”

“Sure. Let me tell you about the bath I took the other day….”

He groaned. Eventually, they hung up, and Jazz went to take the coldest shower in the history of cold showers. He tried not to think of Connie in the shower, too, but that task wasn’t particularly easy to accomplish. He had a very, very vivid imagination.

Emerging dripping and freezing, he wrapped a towel around his waist and headed back to Billy’s old room. His clothes were scattered on the bed, so he picked through them for an outfit, shoving aside the sheets of paper.

But he just couldn’t let them go. Every time he touched those papers, it was as though they had some sort of psychic/magnetic attraction to him. He felt compelled to read them every time. This time was no different—cold and half-naked, he scanned his father’s letter, then looked over the Impressionist’s vile “shopping list” and its strange appendix.

And that’s when he saw it. And once he saw it, he couldn’t unsee it. In fact, he wondered how he could have possibly not seen it until now.

UNDER NO CIRCUMSTANCES ARE YOU TO

GO NEAR THE DENT BOY.

LEAVE HIM ALONE.

YOU ARE NOT TO ENGAGE HIM.

JASPER DENT IS OFF-LIMITS.

He blinked and looked again. It was so obvious:

UNDER NO CIRCUMSTANCES ARE YOU TO

GO NEAR THE DENT BOY.

LEAVE HIM ALONE.

YOU ARE NOT TO ENGAGE HIM.

JASPER DENT IS OFF-LIMITS.

In his relatively short life, Jazz had disturbed crime scenes, stolen and tampered with evidence, broken into the morgue, and illegally photocopied official police files. Now he broke most of Lobo’s Nod’s speed limits on his way to the sheriff’s office and compounded his criminal career by breaking the state law about cell phone use while driving; he just kept getting G. William’s voice mail.

“Lana?” he demanded, now having gotten through to the police dispatch line. “Lana, it’s Jasper Dent. Where’s G. William?”

Lana had a thing for Jazz—even seeing him handcuffed late that one night for breaking into the morgue with Howie hadn’t dissuaded her. Now she was flustered, stuck halfway between trying to make small talk with him and answering his question. “Well, he’s—he just stepped—are you okay, Jasper? Can I help you, maybe?”

“I need to see G. William. Is he coming back to the office?”

“Sure. I just saw him pull up. He’s—”

“Tell him I’m on my way,” Jazz said, and hung up. Soon, he pulled into the sheriff’s department lot, parking Billy’s old Jeep right next to G. William’s cruiser. Someone should get a picture of that, he thought.

Inside, he blew past the reception desk, blowing off Lana, who smiled and tried to get his attention. He found G. William in his office, grinning and leaning back in his chair. The sheriff saluted Jazz with a massive mug of coffee that said SUPERCHARGED! on it.

“G. William—”

“Settle down, Jazz. You got ants in your pants again.”

“Is Thurber still here? Has he been transferred yet?”

G. William slurped some coffee. “He’s here. Catch your breath. Stroke at your age is a hell of a thing.”

Jazz took a deep breath and compelled himself to calm down.

“You come on a social call, or is this business?” G. William asked. “ ’Cause I do have some news for you. Somethin’ you might find interesting.”

Okay, sure. Jazz let out that deep breath and let the tension all along his spine dissipate. “Is it about the new coffee cup?” he said with forced friendliness.

“And there’s the keen powers of observation that brought down the Impressionist.”

“You’re stoned on caffeine, aren’t you?”

“I gotta admit—when there’s more coffee in the cup, I tend to drink more coffee. You think this is why my leg feels all numb and tingly?”

“Could be.” Without being asked or invited, Jazz slid into one of the chairs across from G. William’s desk.

“In all seriousness, though,” G. William said, leaning forward, “I should tell you about a couple of things been going on in town.”

“Oh?”

“Yeah. We had three cars parked in no-parking zones yesterday. And Erickson pulled over the Gunnarson girl for texting while driving.”

“And…?”

“Not a goddamn serial killer among ’em!” G. William guffawed, slapping a meaty palm on his desk. “Not a murder, not a maiming, not a missing person! It’s almost like being the sheriff of a small town!”

Jazz allowed himself a tiny grin. “You’re positively giddy.”

“I think I’m entitled. Don’t you?”

It was true. For a small-town sheriff to go after two serial killers in one career was unprecedented, as far as Jazz knew. A return to the petty, mundane crimes of Lobo’s Nod should be celebrated, and G. William had every right to do so.

“I’m glad for you. I really am. But I need—”

“You need something so big and important that you called my cell half a dozen times and then scared the poop outta Lana and then barreled in here like you were on fire. Jazz, you’re seriously gonna give yourself a stroke.”

“Please listen to me,” Jazz said, and then quickly explained Connie’s discovery in New York, along with the acrostic he’d uncovered in the Impressionist’s pocket.

G. William listened, occasionally sipping at his coffee.

“It could be the world’s most incredible coincidence,” he said.

“You don’t believe that for a minute.”

The sheriff shook his head. “I want nothing more in this world than to believe that. I want to believe that there’s no connection between the guy in lockup waiting to be transported to court and the guy killing people in New York. Mostly ’cause that would probably mean there’s a connection to your daddy, too. So, yeah, I want to believe it’s all a coincidence, but I’m not as dumb as I look, which is a hell of a good thing.” He heaved himself out of his chair. “Let’s go.”

Jazz rose to follow him. “Don’t we have to check with his lawyer first?”

“Usually, yeah. But the Impressionist has made it clear that he’s always available to see you. As long as there’s no cops present, you can talk to him whenever and however long you want. You just can’t report it to us or tell us about it, ’cause then it’d be off-limits in court. But hell—he’ll talk to you all day long, if you want.”

“Lucky me,” Jazz muttered.

G. William led him back to the holding cells, which were empty except for the one farthest from the door, in which sat Frederick Thurber, the Impressionist.

He’d been in the Lobo’s Nod jail since his arrest before Halloween. Lawyers from the Nod were fighting with lawyers from just over the state line—where the Impressionist had murdered a woman named Carla O’Donnelly—over which state got to try him first. And then there was a district attorney in Oklahoma who claimed that the Impressionist had also killed someone in Enid, long before taking on his Billy Dent–inspired sobriquet and modus operandi. Fortunately, the federal government was staying out of it—for now—preferring to let the states waste their time and resources. All three jurisdictions in question had the death penalty, so Thurber was heading for Death Row one way or the other, the feds figured.

The whole thing was a snarl of legalese and lawyerly posturing, the upshot of which was that Thurber remained in Lobo’s Nod until everyone could agree who would get the first pound of flesh from him.

Thurber glanced up as the door to the holding cells opened, then sat up straight when Jazz came through the door. Jazz thought maybe there was a small smile playing across his lips, but who knew what it looked like when a madman like the Impressionist smiled? Jazz kept his face impassive, his spine stiff, as he approached the Impressionist’s cell. The Impressionist stood and turned to the front of the cage, staring as though the bars didn’t exist and he could walk right up to Jazz if he wanted.

“Now, I can’t stick around, so I’m just leavin’ you with a warning,” G. William said sternly. “Don’t even think about hurting him.”

“I won’t get close enough to the bars for him to touch me,” Jazz assured him.

“I wasn’t talking to him,” G. William said wearily, and left.

Alone, Jazz didn’t get the chance to speak before the Impressionist said, in a voice oddly high and thin from disuse, “Jasper Dent. Princeling of Murder. Heir to the Croaking.”

The Croaking? Was this crap for real? He’d almost forgotten how completely delusional the Impressionist was. Thurber thought that Billy Dent was a god, that Jazz was destined to the same divinity.

“Come to learn the truth?” the Impressionist asked. “Come to accept your destiny? It’s not too late. It’s never too late. Jackdaw!”

The man was babbling. He was falling apart, Jazz realized. That made no sense. He should have been doing well. Serial killers tended to thrive in rigid, institutional settings. He’d read all sorts of case studies on guys like Richard Macek, who had turned into a model prisoner once incarcerated. When given limited options and no freedom, sociopaths tended to default to a sort of relaxed ennui. But the Impressionist was blowing the curve for the rest of the class. His eyes were glassy and possessed.

Well, there’s an exception to every rule. And you just met him. Jazz almost felt sorry for the man, but he thought of Helen Myerson and he thought of blowing air into Ginny Davis’s lungs, his hands slick with her blood. He thought of Howie, near death in an alley, slashed open by the Impressionist.

“I want to know about Ugly J,” Jazz said firmly.

Sociopaths never revealed anything; they were masters at concealing their emotions or of feigning emotions to cover when they knew a lack of affect would draw attention to them. He’d expected either a calm, savvy, knowing grin or a flat, reactionless glare.

Instead, the Impressionist actually took a step back; his hands twitched as though he would bring them up to shield himself, to ward something off. If Jazz didn’t know better, he would say the Impressionist was actually… afraid.

“Ugly J…” the man whispered. “No. No. Oh, no. Not Ugly J. We won’t talk about that. You’re not ready for that. Even I know that. I defied for you. I touched when I was told not to. But not Ugly J. I won’t.”

Jazz stepped closer to the bars. “Talk to me. What is Ugly J? What does it mean? Or is it a person? Is it a serial killer? Is it what Billy calls himself now?”

The Impressionist shook his head, mute. Jazz came right up to the bars, aware that the Impressionist could make a lunge and grab him.

“Tell me! Tell me about Ugly J!”

“Not ugly!” the Impressionist screamed. “Beautiful!” Considering what the Impressionist thought to be beautiful, that could mean a lot. “Beautiful,” he said again. “But the way you die is so ugly…! So ugly, Jasper!”