Текст книги "The Bee's Kiss"

Автор книги: Barbara Cleverly

Жанр:

Классические детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 13 (всего у книги 19 страниц)

Joe looked wearily at his watch. Half past one. He could have been doing a smoochy tango with Tilly. Joe suppressed the thought and read on.

On a separate sheet were notes hastily handwritten in pencil. The heading this time was ‘At the Admiralty’. The information had, Cottingham declared, come from a fellow Old Harrovian who owed him a favour. ‘Nothing questionable about this,’ he had put in the margin and, keel-hauling his maritime metaphors, ‘all guaranteed above-board and Bristol fashion!’

‘All the info my friend was prepared to pass on is in the public domain. It’s just that the public wouldn’t have a clue where to look. He wished us luck with the case – Dame B. had many admirers in the Senior Service where they appreciate a spirited lady. Pleased to reveal all he could about D. Not popular! Seems to have jumped ship before he was made to walk the plank.’ Joe groaned and vowed to do something very naval to Cottingham if he didn’t get a move on.

‘Rose to the rank of Chief Petty Officer – that would be “staff sergeant” in our terms, I think. Talented wireless operator and very intelligent.’ It was Ralph’s next piece of naval gossip that caught Joe’s flagging attention.

Donovan had been posted to Room 40 at the Admiralty. In the war, the Royal Navy Code-Breaking Unit had employed a large number of highly qualified civilian men and women alongside naval personnel. Wireless specialists, cryptographers and linguists. It was thanks to their skills that Admiral Jellicoe’s Grand Fleet had had the edge on the German navy, presenting itself, unaccountably battle-ready, hours before the High Seas Fleet had left port on more than one occasion. If Donovan had worked for Naval Intelligence he was not a man to be underestimated. Joe was forming a further hypothesis based on this evidence and wondered if it had occurred to Ralph.

No longer ‘Room 40’, the Government Code and Cypher School, as it now was, had moved with its director Admiral Hugh Sinclair down to Broadway nearer Whitehall. Joe was aware that GC&CS used the resources of the Metropolitan Police intercept station run by Harold Ken-worthy, an employee of Marconi . . . Set up by the Directorate of Intelligence, the station operated from the attic of Scotland Yard. What had Nevil said? ‘. . . the people over our heads . . .’ Joe had assumed that he meant superior in authority but perhaps the reference had been a more literal one?

Joe looked up nervously at the ceiling. Were they up there now? And who were they listening in to? The Met intercept unit, he knew, was currently monitoring the proposed miners’ strike. They had uncovered devastating evidence of Soviet involvement and mischief-making. Two million pounds of funds were being provided by the Bolsheviks to foment industrial action and support the miners for the duration of the strike.

Joe’s head was beginning to spin. What was the thread that led from a wartime Room 40 to the interceptors in the attic and what did that have to do with a Wren bludgeoned to death? On the next sheet the writing became ever less restrained, possibly the effect of the contents of the glass whose dark brown ring decorated the page. Joe didn’t need to sniff to detect naval rum.

Three sheets in the wind – Oh Lord! The condition was catching! – Cottingham had added excitedly: ‘Wonder if you’re aware of where the Dame spent the war years before she joined the Wrens?’ In block capitals he had scrawled, ‘ROOM 40. My contact tells me the Dame was valued for her quick wits and perfect knowledge of German – an ideal combination for cracking codes and interpreting signals. No wonder she was much admired! She was thought to be intime with the boss – “C” no less – Rear Admiral Hugh “Quex” Sinclair, Head of NI, SIS, GC&CS and all the rest of the alphabet soup.’

Joe remembered that the stylish and able Admiral’s nickname was ‘Quex’ from the title of a West End play, The Gay Lord Quex, the wickedest man in London. He had a reputation for high living and had reputedly moved the headquarters of Naval Intelligence to the Strand so as to be near his favourite restaurant, the Savoy Grill.

‘It’s entirely possible that the Dame met Donovan here in Room 40!’ Cottingham had added. ‘Dame B. was highly regarded in naval circles for the undaunted way in which she set about reconstituting a women’s service although it was officially disbanded in 1918. She has collected about her, with the navy’s knowledge and approval – though without financial support or official recognition – a corps of girls whose aim is to carry on the traditions of the service. A sort of mob of Vestal Virgins, if you like, who tend the flame until such time as it shall be needed. They’re top drawer, apparently. Daughters of very high-placed officers, that sort of thing. Some of the chaps sympathize with Bea’s view that the navy has not fought its last engagement and next time they must be fully prepared. Not sure who they see as the enemy but the most likely candidate must surely be the Russians?

‘They considered her a pretty stylish lady. Very much ones for nicknames, sailors! They’ve called this embryonic service of busy young girls “the Hive” of which the Dame was – naturally – Queen Bea.’

It occurred to Joe that they had been so taken up with the forensic aspects of the case, he’d not done what he usually did early in an enquiry. He’d not drawn up a detailed portrait of the murder victim. He remembered that the Dame’s diary revealed a dinner date with an admiral. He’d taken time to send out a signal cancelling on her behalf and breaking the news of her death, but perhaps the engagement itself had been significant? With frustration he acknowledged that he would never discover its significance now an embargo had been placed on his interviewing.

Feeling that the time had come to get to know Beatrice more intimately he picked up his briefcase, put away Cottingham’s notes and checked the contents of a small envelope. He took out the door keys Tilly had found in the Dame’s bag.

‘Time to pay you a dawn call, Queen Bea,’ he said.

Chapter Eighteen

‘Not early risers.’

Tilly had dismissed the inhabitants of bohemian Bloomsbury with a disapproving sniff. Joe hoped she’d got it right. He didn’t want to be observed stealing into the Dame’s flat at five in the morning. Too embarrassing if someone noticed him and alerted the beat bobby. He’d taken the precaution of putting on protective colouring in the form of a shabby brown corduroy suit, much scorned by his sister, a shirt, tie-less and open at the neck, and a wide-brimmed black felt hat which he tugged down over one eye. He looked at himself critically in the mirror and grinned. He thought he looked rather dashing. And, with his dark features etched by lack of sleep, he’d probably pass a dozen similar on their way back from a night spent on the tiles or behind some blue door or other.

He left his car in Russell Square Gardens behind the British Museum and made his way unhurriedly past the building sites into Montague Street and turned into Fitzroy Gardens. He was not a tourist, he reminded himself; he was not here to enjoy the greenery in the central garden or the Portland stone Georgian architecture. He made his way straight to a house at one end of the graceful crescent, noting the side access and wondering if he would choose the right one of the two keys to gain entrance through the imposing front door. A passing milk float clanked by, jugs rattling, and the milkman greeted him cheerfully as he ran up the four front steps.

Tilly had mentioned the Dame’s ‘flat’ but Joe noticed there was only one doorbell. The door opened smoothly, answering to the larger of the two keys, and he walked into a wide, uncluttered hallway. He paused uncertainly, his cover story ready against a challenging occupant. No one hurried forward indignantly to ask him what the hell he thought he was doing there. Again, there were no signs of multiple occupancy. No doorways were boarded up, there were no handwritten signs with arrows pointing to the upper floors, no table spilling over with post to be collected by other inhabitants. Joe concluded that the Dame must own the whole of the house. He stood and listened. The house had the dead sound of a completely empty space.

Boldly, he called out, ‘Beatrice! Are you there?’

Receiving no response, he opened the door to the drawing room.

What had he expected? Emerald green walls, disordered divans piled high with purple cushions, post-Impressionist daubs, an attempt to recreate the Bakst decor for Scheherazade? Yes, he silently admitted that he had expected something of the sort. He had thought that the Dame, having chosen to live in Bloomsbury, would be playing up to the artistic, insouciant style its inhabitants were renowned for. The room surprised him. Modern but restrained, it was obviously decorated by an amateur with a strong personal style.

The walls were a pale string-colour, the wood floor covered in Persian rugs in browns and amber, the large sofa was of black leather. He ran his hands covetously over a piece that might once have been called a chaise longue but this was a sleek, steel-framed extended chair of German design. There was a good supply of small tables, set beside matching chairs of a blond wood inlaid with a pleasing pattern. Joe was interested enough to turn one over to see the manufacturer’s name. Austrian, but available from Heal’s in the nearby Tottenham Court Road. Over the fireplace hung a large and lovely seascape, the other walls carried pictures in a medley of styles: a French landscape, a study of horses that might – but surely couldn’t? – have been by Stubbs, two golden watercolours of an Eastern scene by Chinery and a small Augustus John portrait. They had nothing in common except the owner’s taste, he decided, and again wished that he had met Beatrice in the living flesh. Unusually, there were no family portraits or photographs, nothing of a personal nature.

He counted the seating places and reckoned that the Dame could entertain eight or ten people if she wished. And entertain in some style. She could have invited the First Sea Lord, his lady wife and his lady wife’s maiden aunt for cocktails and they would have been charmed. All was correct and elegant, apart from one object he’d spotted on the mantelpiece – a modern bronze of Europa riding half naked and garlanded on the back of her bull. But it was a work of art and only erotic if you had eyes to see, he thought, and were nosy enough to pick it up and view it from an unusual angle. He paused to handle respectfully a chrome and white table lighter and its matching cigarette box. Removing the lid he sniffed the contents. Turkish at one end and Virginian at the other. Nothing more sinister was going to be on offer in this proper setting.

Shrugging off his fascination for the decorative contents of the room, Joe left to survey the rest of the house. He would return to carry out the correct procedure for checking the contents minutely when he’d got his bearings. The rest of the ground floor was less interesting. The dining room was furnished but looked as though it had never been used, the kitchen and pantry were soulless and bare of contents. A refrigerator, he noticed, held bottles of champagne and hock but that was all. Upstairs was a bathroom, simply appointed but with the luxury of a shower, and two furnished bedrooms. The larger of the two, at the front of the house overlooking the public garden, was level with the tops of the plane trees and decorated in green and white. Obviously the Dame’s bedroom: the wardrobes were full of her clothes, the dressing table held cosmetic items and a flacon of her perfume which seemed to be Tabac Blond. He admired the square bottle with its pale gold disc and exuberant gold fringe tied carelessly around the neck and lifted the glass stopper. A dark, challenging scent of forest, fern and leather intrigued him. The woman who would wear this he could imagine taking the wheel of an open-topped sports car, perhaps pausing to pull on, but not fasten, a leather flying helmet before she put her foot to the floor. For a moment he pictured himself in the passenger seat with the Petit Littoral zipping past in the background. He put the genie of imagination back in the bottle with the stopper and made for what he took to be the guest bedroom at the rear of the house.

At last he had found a jarring note. The disordered divan – it was here! Large, low, plump and covered in a silk of a rich exotic colour which he thought might be mulberry, it was all he understood to be bohemian. Cushions, tasselled, striped, silken, spilled over on to the floor. There was no other furniture apart from a black and gold lacquer screen which cut off one corner of the room. Joe automatically checked behind it, finding nothing but an embroidered Chinese robe and a discarded silk stocking. On the wall behind the bed was a striking painting. He recognized the style. Modigliani. A stick-like girl who ought to have been deeply unattractive managed somehow with swooning eyes and horizontal abandoned pose to convey a feeling of eroticism. He found the decor stagey, the theatricality underlined by two oversized fan-shaped wall lights. The atmosphere was oppressive, the room airless and scented with something which, worryingly, he could not identify.

He walked to the single window and pulled apart the heavy gold draperies. The fresh green of the wild garden below accentuated the tawdriness of the scene behind him and he opened the window to let in some spring-scented air. Leaning out, he saw that the back garden was bounded by a mews building and a high wall with a door in it. Very adequate rear access, his professional self told him. Comings and goings not effected through the front door could be kept a secret from the neighbours.

He closed up again and looked around him. Was this where she conducted her rendezvous with Donovan when not at the Ritz? The floor appeared to have been recently swept; he could not fault the standard of housekeeping in this or any of the rooms. Without much hope of success, he took out his torch and hunted about on hands and knees on the floor looking for traces of a masculine presence. Something white between the floorboards drew his attention. Using a pair of tweezers borrowed from the Dame’s dressing table, he pulled out, to his disappointment, nothing more than a squashed cigarette end from between two floorboards. No lipstick on the end. It seemed to have started life as a Senior Service. Joe could imagine Donovan’s taunting smile. The Commander on his knees carefully examining one of his discarded fag-ends – this was a moment he would have enjoyed.

Surprisingly the other rooms of the house were empty. A few stored pieces of furniture under sheets were all that rewarded his search. What was going on? Had the Dame bought this house as no more than a property investment? If she had, he could only congratulate her on her foresight. But he had a feeling it was more than a financial manoeuvre. It was a setting, a shell, though a lovely shell. The drawing room made a public statement about her; the rear bedroom was where she really expressed herself.

He shook himself and prepared to search thoroughly. He disliked this part of the job and would, in normal circumstances, have assigned it to a sergeant. He was carried through it by the strict and still automatic procedure acquired in his training.

He was baffled. The place was virtually clean. He thought he’d struck gold when he found a black-stained oak cabinet containing files. A rummage through them revealed handwritten notes on cryptography, some of them on Admiralty paper. No secrets here, he assumed. Documents of value would never have been allowed to leave Room 40. Perhaps she was practising at home? A manual on the Spanish language seemed to have been well thumbed as did an Ancient Greek primer. A bookshelf held copies of popular modern novels, all read, and a selection of classics, not read. There were no romances, there was no poetry. The writing desk was a disappointment; though well stocked with cards and writing paper, there was no incoming post. Not a single letter.

He concluded that wherever she lived her life, it was not here. He wondered briefly what signs of his existence, if he were run over and killed, would be found in Maisie’s neat home. A whisky bottle? He locked the front door behind him with the uncomfortable feeling that the lady had answered none of his questions but had teasingly set a few more of her own.

If Beatrice was not to be found here, then where was she? Cottingham had early in the process checked her car and found nothing. The only remaining location, and he sighed as he contemplated the task, was her own rooms at King’s Hanger. Audrey’s death, he was convinced, flowed from that of her employer and would only be accounted for when he understood why the Dame had died. Whatever the authorities were saying – and he could perfectly well understand their protective stance – his instincts told him that she had been killed in an uncontrollable fit of hatred. And the behaviour and character that could engender such a deadly emotion normally left traces: correspondence, journals, family albums, gossip. Joe was confident that he would pick up something rewarding between the layers of Beatrice’s life if only he were allowed access to it.

His mind flew to King’s Hanger, evaluating his chances of invading the house. How in hell was he to talk his way past the old lady? An encounter with Grendel’s mother would have filled him with less dismay. With a wry smile, he suddenly saw his way through the problem. Could he possibly? It would take a lot of cheek and determination. He thought he had enough of both.

He decided that he’d earned himself a good breakfast. He’d make for the nearest Lyon’s Corner House and have his first proper meal in two days. They’d be frying the bacon by now. He’d have two eggs, tomatoes and mushrooms, fried bread, the lot. Then he’d go back to his flat and put his head down for a few hours. He was supposed to be on leave after all.

‘It’s a crying shame, that’s what it is!’

‘Let’s just get on with it, shall we, Mrs Weston?’

‘But all these dresses? All this underwear? And look at these good coats! There’s folk in the village with nothing to their backs as could do with something like this. I can understand the old girl wanting to get rid of her papers and books and suchlike – I mean, what use are they to anybody? Just a sad reminder, really. But it’s not right that everything should go on the bonfire! I call that real uncaring.’

‘Ours not to reason why. The orders are quite clear.’

‘In my last position, housekeeper to the Bentleys, when Miss Louise died, all her things were divided up amongst the female staff. I got her Kashmir shawl. This is a very peculiar household if you ask me, Mr Reid, and if I had anywhere else I could find a position within five miles of my old ma, I’d be off like a shot!’

‘You have a good position here, Mrs Weston. Be thankful for it.’ Reid turned to two young boys who were standing by. ‘Jacky! Fred! Clear those files off that shelf . . . Put them into that box . . . Yes, those as well . . . Take them straight down to the boiler room. Papers go in the furnace. Clothes go on the bonfire in the vegetable garden. Come on! Step lively, lads!’

A figure in the shadows on the landing stood watching silently as Jacky and Fred thumped downstairs carrying between them the boxed residue of the life of Dame Beatrice.

‘Following her to the flames,’ came the sly thought.

Chapter Nineteen

Joe awoke to the shrilling of the telephone, unsure for a moment why a beam of afternoon sun appeared to be giving him the third degree.

‘Yes?’ he growled.

‘Is that Commander Sandilands?’ asked a male voice he vaguely recognized.

‘No. It isn’t. This is his man. The Commander is away in Surrey for a few days and is incommunicado. He has particularly asked me not to reveal his number to the gentlemen of the press.’

‘Balls, Commander!’ said the voice cheerfully. ‘You put that phone down and you’ll regret it!’

Joe groaned. ‘Cyril! Cyril, the slander-monger. Is the Standard still paying you good money for trotting out that tedious tittle-tattle? Haven’t seen your name on the Society pages for a while.’

‘Ah! You do read them then?’

‘Only the bits I find sticking to my fish and chips. I’d like to help you, old man, but, as I haven’t jilted any duchesses this week or fallen face first into my brown Windsor at the Waldorf, I’m afraid I wouldn’t be of any interest to you. Bugger off!’

‘No! Hang on! I’m not on Society any more. They’ve transferred me – promoted me – to current affairs. And I don’t want a favour. I’m offering one. Just for once I think I can do something for you, Commander. Why don’t we meet for a drink?’

‘How many good reasons do you want?’

‘Oh, come on! I thought we could go somewhere quiet and drink a farewell toast to a Wren –’

‘Oh, for God’s sake! Not still barking up that tree, are you? It’s been cut down, man! Look – where are you? Fleet Street? Make it the Cock Tavern . . . upstairs in one of their little booths. That should be quiet enough.’

‘No. Won’t do. Too many nosy journalists about and I’d have thought a stylish lady deserved a more salubrious setting for a send-off. I have in mind the Savoy. The American Bar. You can treat me to one of Harry’s cocktails. Six o’clock it is then!’

He rang off before Joe could argue.

Cyril Tate had been an odd choice for Society columnist. Joe wasn’t surprised to hear that he’d been moved sideways, having privately considered the man too astute, too talented and too middle-aged to be wasting his time trailing around after debutantes. When his copy escaped the editor’s blue pencil, it was lightly ironic and certainly lacked the deferential tone the readers of such nonsense expected. He was valued, Joe supposed, by his paper for the quality of his writing but also for his talent with a camera. Readers were increasingly demanding photographic illustrations of their news items and papers like the Standard found that their sales increased in direct proportion to the square footage of photographs they printed. Armed with his Ermanox 858 press camera, he could stalk his prey up close and then write the reports to support the photographs. Only one pay-packet. Only one intrusive presence at the scene. Economical and practical.

A confident-looking man in trim middle age and wearing a slightly battered dinner-jacket was standing at the bar when Joe arrived, laughing with the barman. The room was almost empty of drinkers at this early hour and had the air of quiet readiness of an establishment about to launch into something it does well. Everything was in place, shining and smart. Silver shakers stood in a row; the lemons were sliced, the ice was cracked. In a corner, a pianist lifted the lid of a baby grand piano and began to riffle over the keys.

‘Harry’s working on a cocktail for you, Commander,’ Cyril greeted him cheerfully.

‘It’s called The Corpse Reviver,’ said Harry Craddock. ‘Very powerful concoction.’

‘Trying to put me out of a job?’ said Joe.

Harry smiled. ‘Not necessarily. Four of these taken in swift succession will unrevive any corpse.’ He listed the ingredients.

Joe shook his head in disbelief. ‘Thanks all the same but I’ll stick to something simple. What about you, Cyril?’

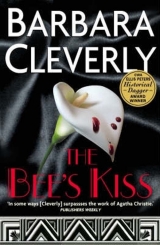

Cyril was prepared. ‘The Bee’s Kiss,’ he said. ‘I’ll toast the Queen Bea with an appropriate potation.’

Harry deftly measured light and dark rum into a cocktail shaker, adding honey, heavy cream and ice. He shook it lustily and poured the golden foam into a cocktail glass which he presented, with a flourish, to Cyril.

Joe eyed it doubtfully. ‘Spoon? Are you having a spoon with that?’

Cyril took a sip and licked his lips. ‘Delicious! Looks so innocent, doesn’t it? Honeyed, frothing, inviting? But beware – there’s a sting in there! Too much of this and you’re on your back and feeling ill. Have one?’

‘No thanks. I don’t drink rum these days. I’ll have a White Lady.’

‘Ah, yes. Army, weren’t you? I expect it would put you off.’ His sharp eyes crinkled with humour. ‘Not a problem for me. Ex-Royal Flying Corps – they tried to keep us well clear of intoxicating spirits!’

They took their drinks to a secluded table.

‘Right, Cyril,’ said Joe, ‘that’s enough of the heavy symbolism. Get to the point, will you? I’m a busy man.’

‘Are you though?’ The tone was annoyingly arch. ‘You confirmed on the telephone information that had been put my way by an official source. You’re off the case. You’ve been left sitting twiddling your thumbs – just like you left me at the Ritz the other night.’ He gave Joe a forgiving smile.

‘Ah! That was you?’

‘None other. And I mean – none other. Everyone’s been discouraged from taking an interest but I’m not so easy to put off.’

‘And you have contacts.’

Cyril didn’t reply. Joe wouldn’t have expected it. Journalists were skunks but they all had honour when it came to refusing to name their sources. He was surprised when Cyril said, ‘The Irishman. I’d say – watch him, Commander . . . if you were still allowed to watch him. He’s the link between my two areas of expertise, you might say.’

‘Not sure I follow you, Cyril.’

‘Well, covering this crime story, as I was – my headline was going to be “Mysterious Death of Wren at Ritz” – it occurred to me that I was particularly well placed to have insights, what with my society background an’ all.’

‘Do you have them often, these insights, and are you prepared to share them with me?’

‘You know about the Hive?’ Cyril’s voice had become businesslike and low.

‘I know it exists. Nothing more. Peripheral to my enquiries?’

Cyril shook his head. ‘I don’t believe so. Listen! These girls that buzz about getting ready to save the country, sharpening their stings ready for the Russian bear . . . know who teaches them their skills? Down at the Admiralty building, there’s a room that’s been set aside for their use and one of their instructors is our friend Donovan.’

‘Skills? What sort of skills?’

‘Wireless training – intercepts, code-breaking, signalling. The sort of stuff the girls were good at in the war.’ He paused and sipped again at his cocktail. ‘It just occurred to my suspicious mind to wonder whether the bloke might have extended his brief somewhat.’

‘I am aware of the man’s extra-curricular relationship with the Dame,’ said Joe carefully.

‘Well, push the thought a bit further. Good-looking bloke. Heart-breaker perhaps? What do you say to him being the honey in this nasty little cocktail?’

‘Girls apt to develop a crush on the teacher, you mean?’

Cyril sighed. ‘This is more than the plot of a girls’ school story, Commander. Frolicksome larks among the Wrens . . . I’m talking about sinister manipulation.’ He reached out and touched Joe’s arm to underline his earnestness. ‘Sinister enough to lead to death.’

‘Death? Whose death?’ asked Joe uncertainly.

‘Ah, well. This is where the lighter side of my job gives me that insight I mentioned. Not sure anyone else has made the connection. There’s only about six girls in this group. They’re crème de la crème – intended to form the core of any future organization. What would you say if I told you that two of them had killed themselves? Over the last two years. Committed suicide. Coincidence? Two out of six? I don’t think it could be. Hushed up, of course. I only took notice because they were both on my socially-interesting list and now, when I come across a third death connected with this little set-up, I begin to smell a rat – and perhaps a good story.’

‘Are they sure it was suicide?’ Joe asked awkwardly, uncomfortable to be professionally on the back foot in this discussion.

‘No doubt. There were valid reasons, farewell notes and all that. One jumped off a cliff in the middle of a family picnic, the other took an overdose of something no one suspected she had access to. They’ve been replaced with fresh recruits, of course. But it makes you think. You’d no idea, had you?’

‘Cyril, the Dame only died three days ago. I’d have got there.’

‘Never will now though, will you? You’ll read the official story of her death in tomorrow’s paper. The line we were handed is that her companion –’

‘Don’t tell me! I practically dictated it,’ said Joe. ‘And don’t dismiss it. It’s certainly possible.’

‘Plausible at best.’ Cyril gave him a knowing look. ‘So you’re off the case and sent to Surrey?’

‘I’ve a few days’ leave lined up.’

A waiter approached and Cyril ordered fresh cocktails. When the man had moved out of earshot he said carefully, ‘And it mightn’t be a bad idea to be out of the capital over this next bit.’

‘The strike, you mean? It’ll affect the whole country. Even deepest Surrey.’

‘Not talking about whether the trains are running or the milk’s delivered to your doorstep – I’m talking politically.’

Joe was silent, afraid he knew where this was leading.

‘Word is you were something of a hot-head not so long back, Commander. Union man? If all this turns nasty, people will go about looking for bogeymen. Lists are being drawn up so that if heads have to roll the chopping will be done in an orderly way . . . with military precision,’ he said with emphasis.

‘How would you know all this, Cyril? Home Secretary your cousin or something?’

‘I’ll just say I have a fellow pen-pusher on a grander sheet than mine who’s well connected. He occasionally gets hold of stories that he’d never be allowed to print in his august journal. But if another less hidebound paper with a forward-looking owner who’s not so impressed by the British Establishment breaks it first, he can then follow suit the next day – once it’s in the public domain. That’s how it works these days – regulated revelation, you might call it. But the upshot is – and I say this because you’ve done me a good turn in the past –’ Joe couldn’t for the life of him remember what it was – ‘check your slate’s clean. Keep your head down until this has blown over. Someone’s got his eye on you.’