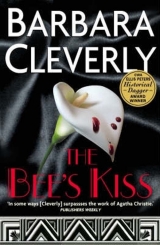

Текст книги "The Bee's Kiss"

Автор книги: Barbara Cleverly

Жанр:

Классические детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 12 (всего у книги 19 страниц)

Chapter Fifteen

Their taxi was turning into Park Lane and Joe was suddenly aware that time and opportunity were slipping away from him, the case already beyond his control. He leaned forward. ‘Slow down, cabby, will you?’

It wasn’t the first time the driver had received the command. He grinned and obligingly began to hug the kerb, moving along at ten miles an hour.

‘Good idea, sir. We’re nearly home. You could come in if you like but I wouldn’t advise it. My father always waits up. He’s got a little list of men he perhaps won’t set the dogs on just yet and you’ve been added to it. In fact you’ve moved up to a jolly high position. He tells me he “likes the cut of your jib” or something. Thought I’d better warn you.’

‘I’m on quite a few lists,’ said Joe lightly. ‘I’ve got very slick at smooth take-offs down driveways. I particularly favour the laurel-lined ones.’

Tilly reached for his hand and squeezed it. ‘Goodness, you’re easy company, Joe,’ she said softly.

‘It was Joanna,’ she went on hurriedly.

‘Joanna? What was Joanna?’ Joe’s senses were still reeling from the sudden show of warmth and – could he have been mistaken? – affection.

‘The recipient of the Dame’s signal was Joanna herself.’

‘Eh? But why on earth . . .?’

‘My friend may look as though she’s sculpted out of the same stuff as a sugar mouse but don’t be deceived!’

‘I expect hobnobbing with Monty would open a girl’s eyes to the world?’

‘Well, Joanna’s not averse to a little hobnobbing from time to time but not with Monty.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘She told me she’s been keeping him dangling. No hanky-panky before marriage. She’s quite cold, you know, tough and rather businesslike. Monty may not look much of a catch to you but, believe me, he’s not despised in the matrimonial stakes. He’s got a title and expectations of something even grander when his grandfather dies. And the old boy is rumoured to be on the rocks and breaking up fast. Monty’s got connections on the Joliffe side as well and there’s money there.’

‘He’ll be needing it! The cad’s got expensive and dangerous tastes.’

‘Yes. I got a feeling that all may not be quite as it seems with the Mathurin finances . . . I was offered a close look at her engagement ring. It was big but old-fashioned. I’d say he’d pinched it from his granny not offered Joanna her choice of the sparklers on display at Asprey’s.’

Joe wondered for a moment how he was going to manage without Westhorpe’s female insights and her unique access to the powder rooms of London.

‘But Joanna’s tale backs up Audrey’s version of Dame Bea’s proclivities, sir. She was prepared to have quite a laugh about it. She wouldn’t have shared the confidence with most girls but she knows what I do and assumes I’m not about to have a fit of the vapours at the revelation. During the party Beatrice joined them and made herself very agreeable to Joanna. She must have seen something in the girl that Joanna is not admitting (to me at any rate) is there because she made a louche suggestion. She invited Joanna to come up to her room. Right there in front of Monty! Joanna can’t be certain that he didn’t overhear but he made no comment.’

‘So the Dame flung her a last come-on, vampish look from the door and disappeared. No wonder Armitage missed it. He was scanning the blokes for a reaction! Explains why she left her door unlocked if not open, perhaps even called an excited, “Do come in!” to her killer,’ said Joe with a shudder.

‘But who came through the door? Cousin Monty seeing red and prepared to wield a poker to avenge his fiancée’s honour? I can’t see it, sir. Even if he could have got away unseen from the party.’

‘Not for honour. I don’t believe Monty would wield so much as a fish-knife for honour. Oh, Lord! We’re here! All lights on, I see. A moment, cabby . . . Look, Tilly, no notes, remember! This was an entirely unofficial evening. But most enjoyable . . .’

He would have said more but she turned to him and put a finger firmly over his lips. ‘I had a wonderful time! Goodnight, Joe.’ A swift kiss on his left cheek and she was gone.

He sat on, wrapped in disturbing thoughts and wishing he hadn’t drunk so much champagne.

‘Where to now, sir?

The cabby’s tactful question stirred him to say decisively, ‘Scotland Yard. The Derby Street entrance.’

‘Young lady nicked your watch in that last clinch, did she, sir?’

Joe laughed. ‘No. Not my watch.’ As though to double-check, he ostentatiously consulted his wristwatch. Well after eleven. What the hell did he think he could achieve at this late hour, boiling his brains over a stillborn case? He thought there might be waiting on his desk a delivery of notes from Cottingham who’d been sent off with a day’s steady police work under his belt before the axe had fallen. Joe was feeling too agitated to go straight home and he didn’t have the effrontery to face Maisie’s sharp tongue and knowing comments in his evening dress with lipstick on his left cheek and reeking of champagne and cigars. An hour’s clandestine work would steady his jumping thoughts. Scotland Yard never slept. Lights were on from top to bottom of the building when he left the taxi. The uniformed man at the entrance saluted him and waved him through. As he passed the reception desk on his way to the stairs, he was hailed urgently by the duty sergeant.

‘Sir! Commander Sandilands! This is a piece of luck! We’ve been trying to get hold of you. Something’s come up. All too literally, sir! There’s a couple of river police here won’t go away until they’ve seen you.’

Joe approached the desk in puzzlement and the sergeant opened the office door behind him calling, ‘Alf! George! Got him! He’s all yours.’

Alf and George slammed down mugs of cocoa, bustled out of the office and stood, giving him a slow police stare. They were wearing their river slickers and naval-style peaked caps and very purposeful they looked. The leader glanced uncertainly from Joe back to the duty officer, who swallowed a grin and said, ‘Yes. This is who you’ve been waiting to interview. Commander Sandilands.’

‘Off duty,’ Joe muttered, aware that he looked as though he’d just strolled off-stage from his bit-part in a society farce at the Lyric. ‘Sandilands it is. Tell me what I can do for you.’

‘What you can do for us is identify a corpse, sir. It’s down at the sub-station by Waterloo Bridge. It’s a fresh one – only been in the water an hour at the most. A suicide.’

‘I’d like to help, of course,’ said Joe, stifling his irritation. ‘But suicides are not my department. Can’t you just go through your usual channels?’

The last thing he wanted was to be lured away to that stinking hole down by the bridge. The river police, the only arm of the service the people of London had ever really taken to their hearts, were a force Joe could admire too but he wanted nothing to do with them this evening. As well as coming down hard on theft, piracy and smuggling in the docks they managed also to patrol the sinister reaches of the Thames which were favoured as the last resting place of unfortunates driven to take their own lives. Sometimes the three-man crews were so quickly on the spot in their swift river launches that bodies were netted and fished out before they’d breathed their last, and in that cold, stone, carbolic-scented little room by the arches they would squeeze and pummel the victim laid out on the canvas truckle bed until, willing or not, the dank river water spewed out of the lungs to be replaced with the breath of life.

‘Regular channels no use, sir. It’s you we have to see. Just to take a look at the body before it goes off to the morgue. Won’t take you a minute and it will save us hours.’

‘Why me?’ Joe shivered. The evening’s euphoria had evaporated, leaving him full of cold foreboding.

‘No identification to be found, sir. No documents, no labels on clothing, nothing at all. Except for one item in her pocket.’

‘Her pocket?’

‘Deceased is a young female, sir.’

He fumbled under his cape and held up a small white object.

‘We were lucky we got there before the printer’s ink ran. You can just make it out.’ He read from the card: ‘“Commander Joseph Sandilands, New Scotland Yard, London. Whitehall 1212.”

‘It’s your calling card, sir.’

Chapter Sixteen

For a moment, Joe’s face and limbs froze. When finally he found his voice it rapped out with military precision: ‘Waterloo Bridge. We’ll never get a taxi at this time of night. Half a mile from here? We can run it in five minutes.’

He was sprinting out of the door before the river police had pulled themselves together. They pounded after him, boots thumping, capes flying.

As the door swung to behind them, the duty sergeant caught the eye of a passing constable who’d loitered to witness the strange scene. ‘’Struth! That got him moving! D’you see his face when the penny dropped? Wonder how many girls the old fart’s given his card to lately?’

‘Sounds like a case of unrequited affection to me,’ commented the bobby sentimentally. ‘Probably got some poor girl up the stick.’

Joe pounded along the Embankment, evening shoes giving him a perilous grip on the wet pavings. He looked ahead through the half-grown trees lining the river to the shimmering line of pale yellow lamps studding the bridge along its great length. Cleopatra’s Needle. More than halfway there. He tore off his tie and cracked open his collar. He pushed on, glad to hear his escort panting and cursing close behind.

Three young females. He’d given his card to three and that only yesterday. With dread he listed them. ‘Audrey, Melisande . . . And her baby . . .’ His heart gave a lurch which threatened to cut off his breathing as he added, ‘Little Dorcas.’

He could have asked the sergeant one simple question which would have reduced the choice to one: blonde, auburn or black hair? He knew very well why he’d not asked. One answer from the list would have been more than he could bear and he could not risk showing emotion right there at the reception desk.

It must be Dorcas, he decided. Driven to distraction by her grandmother’s cruelty she’d run away to London, swelling the numbers of waifs and strays who fetched up on the cold streets of the capital in their thousands. He’d been kind to her. Armitage had paid her flattering attention. Perhaps she’d been trying to contact one of them? He ran on. Without a word spoken, they all stopped and, hands on knees, gasping for breath, they tried to gain a measure of control before they entered the dismal little rescue room. The older of the two officers flung him a wounded look. ‘It’s all right, sir. She’s not going anywhere, whoever she is. Five minutes is neither here nor there for the deceased.’

‘It’s a bloody eternity for me,’ said Joe with passion.

A tug hooted mournfully, echoing his words. A sickening stench of decay belched from the ooze below. It was low tide and several yards of stinking mud fringed the sinister black slide of the river.

‘Let’s get on with it, shall we?’

They exchanged looks, nodded and went inside.

A third river officer was sitting over his tea, a brimming ashtray on the floor at his feet, filling in the crossword on the back of the Evening Standard. He shot to attention as they entered. In the centre of the room on a still-dripping truckle bed lay a white-shrouded figure. The cocktail of carbolic and Wimsol bleach was almost a relief after the river smells. As Joe advanced to lift the sheet he started in horror to hear a voice behind him intoning:

‘One more unfortunate,

Weary of breath,

Rashly importunate,

Gone to her death!

Take her up tenderly,

Lift her with care,

Fashioned so slenderly,

Young and so fair!’

Joe turned and addressed the sergeant angrily. ‘Who or what in hell is that?’

The sergeant’s voice was a placatory whisper. ‘Witness, sir. He was on the bridge when she jumped.’

A bear-like figure shambled forward into the light shed by the solitary electric bulb and presented himself.

‘He’s a down-and-out, sir. Harmless. We know him well. Came forward with information and we asked him to stay in case a statement was required. Name of Arthur.’

Joe turned to the man. ‘Arthur? Thank you for staying. And thank you for your sentiments. Now, gentlemen, shall we?’

The constable moved reverently to turn the sheet back.

Joe stared.

‘Young female,’ the elderly sergeant had said. And, in death, wiped clean of coquettish artifice, her doll’s face framed by a mop of curling blonde hair, Audrey had shed the years along with her life.

‘Known to you, sir?’ the sergeant enquired gently.

‘Yes. Audrey Blount. Miss Audrey Blount. I can give you her address. Two addresses in fact. She has a sister in Wimbledon, I understand. I interviewed her yesterday . . . was it yesterday? . . . Sunday, anyway. It was Sunday. You can have her taken to the morgue now. I’ll arrange for a police autopsy. Not usual, I know, but there are special circumstances. I’ll see that her next of kin are informed. Look, can you be certain it was suicide?’

‘Better have a word with old Arthur, sir. He’s very clear on what took place, you’ll find.’

‘I’d like to do that.’ He cast an eye around the crowded and unpleasant room. ‘But not here. I could do with some fresh air. How about you, Arthur? Shall we go up on to the bridge and you can tell me all about it?’

‘Here, take this spare cape, sir,’ said the sergeant. ‘Can get a bit nippy up there and there’s a mist rising.’

Joe approached the body and quietly spoke over it a further verse of Thomas Hood’s lugubrious poem. He’d always hated it but here, in these ghastly surroundings, it flooded back into his mind with awful appositeness.

‘Touch her not scornfully,

Think of her mournfully,

Gently and humanly,

Not of the stains of her . . .’

His voice faltered for a moment and the deep baritone behind him finished for him:

‘All that remains of her

Now is pure womanly.’

Joe dashed a hand at his eyes. The sergeant passed him a crisp handkerchief. ‘Here. It’s the carbolic, sir. Fumes can get to you if you’re not used to it.’

‘If we go along to the very centre, I think you’ll find the air is fresher there . . . I’m sorry – I don’t know your rank?’ said Arthur in a tone which would have sounded at home in a London club.

‘Commander Sandilands. CID.’

‘Indeed? How do you do? My name is Arthur as you have heard. Sometimes I’m known, in a jesting way, as King Arthur and this –’ he waved expansively at the great length of the bridge – ‘is my kingdom.’

‘I had understood that gentlemen of the road were discouraged from taking up residence on His Other Majesty’s bridges,’ said Joe, responding in kind to the thespian flavour of his companion’s language.

‘Indeed. But I am happy to say I am tolerated here. This beautiful bridge – and being a man who appreciates the spare, the classically correct, the understated, I concur with Canova that it is the loveliest in London – is much frequented by tourists. Tourists have money to spend and even to give away and I find them very generous, particularly our American cousins. Very large-hearted. But they despise – and are embarrassed to find themselves despising – beggars. So, I entertain them to earn a copper or two. I tell them the history of the bridge; I identify the buildings to north and south from the dome of St Paul’s to the tower of Big Ben and I accompany my perorations with appropriate verses.’

‘I had marked your facility for poetic effusions,’ said Joe. ‘Look, can we stop all this nonsense, cut the cackle and get down to business?’

Arthur smiled. ‘You may be able to converse in the blunt transatlantic mode of recent fashion but I’m not sure I can change my style for a police interview. Though I will try.’

‘What were you in a previous existence? A schoolmaster? A butler?’

A flash of some emotion lit the old man’s eyes as he replied swiftly, ‘I employed both in my time. No matter.’

He quickened his pace and Joe plodded on, glad of the protection of the police cape as a chill breeze sprang up on nearing the middle. Arthur pointed to the central recess jutting out from the level bed of the nine-arched bridge, on the north-east side facing St Paul’s. Behind them, to the left, the lights of the Savoy Hotel shone out their seductive promise of warmth and comfort, a shimmering mirage when, yards away, under Joe’s feet, separated from them by a low balustrade, coiled the black river that had taken Audrey’s life. Joe hated crossing rivers. They were alive. They had a character, snake-like and sinister, which repelled him. He gripped the granite handrail tightly as they looked over. It eased his vertigo but could not dispel it. As they stood looking down with fascination Big Ben boomed out the twelve strokes of midnight.

‘That’s where she was standing.’

‘And where were you?’

‘There in the next recess. I was bedding down for the night.’ Arthur produced two penny coins from the depths of his hairy overcoat and held them in front of Joe’s face. ‘They can’t move you on if you’ve got visible means of support and twopence will pay for a night’s lodging. I always keep twopence handy.’

‘Very well. Let’s go to your recess then you can tell me what happened. Try to keep it short and clear, will you, Arthur? It’s been a long night already and it’s only just midnight.’

‘So I observe, Commander. Time first. You’ll need to establish the time,’ he began briskly. ‘Accuracy guaranteed by Big Ben over there. The lady came along this side of the bridge about two minutes before a quarter to nine sounded. I approached her and she was kind enough to give me a sixpence from her bag. Yes, she had a bag. It was not found with her body. They rarely are. They get washed away and picked up by mudlarks who do not turn them in. Pretty girl, in a good humour, I’d have said. I thought she might have been on her way to an assignation. She had that look of suppressed excitement about her.’

‘She didn’t strike you as a potential suicide?’

‘No. I would have taken strenuous steps to divert her from her intent, had I suspected that.’

Joe thought an intervention by Arthur might just well have tipped the balance. ‘And then?’

‘She stopped in the central bay and loitered. She looked at the river. She looked up and down the bridge. I assumed she was waiting for someone. As she stood there the nine strokes of the three-quarter hour sounded.’

‘Tell me what the conditions were? Light? Visibility? Were there people about?’

‘The gloomiest moment of the day. Exactly halfway between sunset at eight thirty and lighting-up time half an hour later. There was hardly anyone about. It’s a very still time. A couple passed. They crossed to the other side when they saw me. A few taxis went by. The eight forty-five omnibus clanged past on time. I began to bed down so I couldn’t see her any longer but I could hear.

‘A minute or two after she arrived, she greeted someone and held a brief conversation. A few minutes later, before the hour struck at any rate, I heard a shriek though at the time I thought it was a ship’s hooter and then there was a splash. I got up and looked about me and the bay was empty. The lights were not yet switched on and I could see only a few yards in the poor light. I assumed that she’d met her intended and gone onwards to the Embankment.

‘Just after half past nine o’clock I was disturbed by the river police and I volunteered to go with them to offer my observations. I expect they are also seeking the testimony of the last person to speak to her. The one she appeared to recognize. He passed the time of day with me before he approached her.’

‘Good Lord!’ said Joe. ‘Do you know what you’re saying?’

‘I do. I hope I express myself with clarity.’

‘Who was this man? Can you give me a description?’

‘Nothing easier, Commander!’ The old eyes twinkled with mischief. ‘It was a policeman.’

Chapter Seventeen

Joe fought down his surprise and irritation. He thought he would get the best out of Arthur if he showed a little patience and allowed the man to enjoy his moment in the limelight.

‘A policeman you say you know by sight?’

‘Of course. It was the beat bobby. Charming young chap. Always stops for a word. He’s Constable Horace Smedley and he bears the number 2382 on his collar.’

‘And you gave this information to the river police?’

‘Yes. Observe!’ He pointed to the southern end of the bridge. ‘They are acting on it at last. Do you see the red flashing light? They are signalling to Constable Smedley that there is an emergency. As soon as he sees it he will enter the mysterious confines of the blue box atop of which it glows and pick up the telephone therein. He is being summoned to return at once to the sub-station.’

Joe was annoyed to have police procedure explained to him by a down-and-out but he pressed on, keeping his tone polite. ‘Where may we find you if we need to refer to you again for a testimony, Arthur? Are you always to be found here?’

‘In the daytime hours, yes. At night, if trade has been good, I make my way to a Rowton House. It costs one and sixpence a night or six and sixpence for a week for decent, if plain, accommodation and the opportunity to take a bath.’

Joe was familiar with the excellent hostels for the out-of-pocket dotted around London. ‘And which one do you favour?’ he asked, thinking he could guess the answer.

‘The Bond Street branch, of course,’ said Arthur with a smile.

‘Well, here’s a retainer,’ said Joe, fishing two ten shilling notes out of his inner pocket. ‘I would be most obliged if you would make yourself available to the force by residing in Bond Street for the next fortnight.’

‘It will be my pleasure, Commander,’ said Arthur.

Constable Smedley, Officer 2382, presented himself, breathless, at the sub-station minutes after Joe got back there himself. Intrigued and articulate, he was eager to answer Joe’s questions, and, Joe guessed, to enliven what had been a dull beat.

‘So you passed the time of day with Arthur and moved on down the bridge? Tell me about the lady you observed in the central bay.’

Smedley gave a succinct police-approved, training-manual description of Audrey.

‘Tell me why you approached her.’

‘Always do, sir. Lonely lady. She was looking a bit lost. Always the danger of jumpers from this bridge, sir. It’s a favourite. Whichever side they pick, they go down looking at the best view in the city. And the balustrade’s low. Suicides fell off – sorry! no pun intended, sir – while it was being repaired but they’re back now the scaffolding’s been removed. I can always spot ’em!’

‘And you took this lady for a potential suicide, did you?’

The constable considered this. ‘Well, obviously I got it wrong . . . but no . . . she can’t have struck me as such because I let her be and passed on. She greeted me with a smile and some words . . . “Oh, there you are” or something like that as though she was expecting to see someone she knew. Then, realizing her mistake, she fumbled about a bit in her pocket and took out a calling card and looked at it. Checking the details. Even looked at her watch. A bit of pantomime, I thought. Establishing her bona fides on the bridge. For a suicide she was a damn good actress, sir.’

‘Oh, yes, that’s exactly what she was. And it was in her pocket, not her bag?’

‘Yes, sir. Sort of, at the ready. She did have a bag over her arm.’

‘No bag has yet been found.’

‘Wouldn’t expect it. They normally throw their bags over first and then jump.’

‘Good Lord! But, tell me, who else did you see on the bridge as you proceeded on your beat?’

‘No one, sir. I was aware of figures passing along on the other side but nothing out of the ordinary. The eight forty-five omnibus went by. It doesn’t stop on the bridge, sir. It was just about dark and a mist coming up. No lighting for another few minutes. If you didn’t want to be observed throwing yourself off, it was the best time to choose.’

He looked at Joe thoughtfully for a moment, wondering whether to speak out. This Commander, or whatever he was, might look like a music hall turn but he was quiet-spoken, interested and asked the right questions. Smedley chanced it. ‘And a good time to choose if you wanted to help someone off, sir.’

Minutes later Joe was gratefully climbing aboard a tram he’d managed to flag down. It was clanking its way back along the Embankment, returning to the depot, and Joe seemed to be the only passenger. The lonely conductor launched into a cheerful conversation. ‘I won’t tell if you won’t, Constable,’ he said, using Armitage’s tap to the side of the nose to indicate conspiracy.

Joe thought he understood the jibe. He grinned and looked down at his borrowed slicker and the spare peaked cap he’d been kindly handed by the sergeant with the promise that he’d ‘be needing it in five minutes’.

‘’Sawright, mate,’ he said. ‘Don’t ’ave ter plod this next bit. Special dooties. Give us a ticket to the Yard, will you? And don’t spare the ’orses!’

In a spirit of mischief, Joe waited until the stroke of one before ringing Sir Nevil.

‘Sandilands here. Got a little problem, sir.’

‘Sandilands? Joe? What the hell! You’re supposed to be off duty!’ The voice was irritated but not sleepy.

‘I am off duty. I’ve spent the evening at the Kit-Cat and now I’m sitting here in my dinner jacket, full to the gunwales with Pol Roger ’21. You’d say:

“Gilbert the filbert, the nut with a K,

The Pride of Piccadilly, the blasé roué,”

if you could see me.’

‘You’re tipsy! You’re ringing me at this unearthly hour to tell me you’re tipsy? Where are you?’

‘At the Yard. In my office. Just finishing a report for you.’

‘What are you doing at the Yard? You were told –’

‘I came to pick up my motor car. I shall need it tomorrow when I set off for Surrey as per orders. Someone was watching out for me and when I arrived I was shanghaied by the river police who escorted me to their awful lair by Waterloo Bridge to identify a drowned person. It turned out to be Audrey Blount.’

There was a silence at the other end while Sir Nevil rummaged through this mixed bag of information.

‘Audrey was –’ Joe began helpfully.

‘I know who Audrey was. I’m familiar with the file. Get a grip if you can and tell me what happened.’

Joe filled in the details, encouraged by an occasional ‘And then?’ or ‘Tut, tut.’

As he finished, Sir Nevil said heavily, ‘Sad story. But, you know, Father Thames accounts for more murderers each year than the public hangman.’

‘Murderers, sir?’

‘Oh yes. It’s remorse and fear that push them over the edge. Now . . . let me tell you how this sorry business will be construed by the powers-that-be over the road and over our heads . . . It’ll go something like this: Audrey quarrelled with her employer, pursued her to London, as she admitted to you, with the object of killing her and did, indeed, in a fit of rage, achieve her aim. She faked up signs of a robbery and, still harbouring a grievance against her employer, she defiled the corpse in a somewhat unimaginative manner. Very tasteless and amateur attempt! In character, I would have thought. She was seen in the vicinity by a police witness no less. Disguised as a maid, she could have secreted her discarded bloodstained overall in the dirty linen on the trolley and trundled her way, unregarded, out of the hotel.’

He sighed and with affected tetchiness added: ‘Do you expect me to do all your work for you?’

Caught up in the flow of his reasoning, he rattled on: ‘Shortly after, pursued by CID and fearing arrest or simply the victim of conscience, she flees to London and does what hundreds of guilty people have done before her. Leaps off a bridge. Neat, Joe. Neat. This closes the case with a bang. A distressing domestic incident but no more than that. No need now to go on searching the rooftops of London for homicidal burglars. Hotel guests all over the capital may sleep easy in their beds. All round good solution, I’m sure you’ll agree. Have your notes sent to my office, will you? . . . Oh, and, Joe, do take care if you’re driving your car back across London in your state. You sound a bit wobbly to me and some of those traffic police are sharp lads . . . 1921, eh? Excellent year! Excellent! Goodnight, Joe.’

The connection was cut before Joe could protest or question.

Joe was thoughtful. Earlier in the day, Sir Nevil had been accepting but disapproving of the pressure put on them to close the case. Now Joe would have said he was eager to connive in the official clampdown. Something was going on that he was not being told about. He sighed. What to do? Give in and go along with the theories being cooked up?

Beatrice and Audrey. He had looked into two dead faces in the space of two days. He felt the weight of two albatrosses around his neck and sighed.

He was on his own. He could call on help from no one. Tilly and Bill had been discharged from the case and were heaven knows where by now. Cottingham would have to be informed by note that he was to do no further work. Cottingham. Perhaps not quite on his own, yet. There was an envelope lying on his desk addressed to him in Ralph’s hand.

Inside was a sheet dated and headed ‘Informal (underlined) notes for the attentn. of Comm. Sandilands.’ Below this were further confirmatory notes of times and locations of various guests around the hotel on the night of the murder. A follow-up interview with the lift operator revealed nothing new. The inspector had even swabbed the interior of the lift but failed to find bloodstains. The maids’ trolleys were equally clear of blood traces – Sir Nevil would not be pleased! – and the hotel laundry turned up nothing but the usual assortment of human effluvia. ‘Nose bleed in Room 318 duly verified,’ Cottingham had added carefully.

Joe turned at last to Donovan’s alibi. Just as he had told them, the boot-boy had conveniently spent the vital hour with him in his office. Cottingham had put a note in the margin: ‘Give me ten minutes and an extra fiver on expenses and I could break this. Something tells me the rogue Donovan would have a spare alibi up his sleeve, however. Shall I pursue it?’

He went on: ‘Work pattern. Employment not as implied by D. Very much a part-time job. Manager reveals his real work is with the Marconi Company. On leaving navy, he joined this wireless firm. Many did when guns fell silent. The manager of the Marconi Co. confirms that D. works for them in their electronics research department. Does the expression “thermionic valve” mean anything to you, sir? They say this is a full-time 9–5 job but the subject insists on taking time off at irregular intervals. He has a dependent relative who needs his support. (Ho! Ho!) The firm goes along with this because he’s apparently invaluable. A whizz with the wires or air waves or whatever they use nowadays. If he’s moonlighting at the Ritz he’s a busy boy! But he probably still puts in fewer hours than us, wouldn’t you say?’