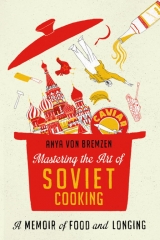

Текст книги "Mastering the Art of Soviet Cooking"

Автор книги: Anya von Bremzen

Жанры:

Биографии и мемуары

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 4 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

Then one Friday Liza returned from school and sat at the Shabbos table staring down at the floor, lips pursed, not touching a thing. She was fourteen years old and had just joined the Komsomol, the youth division of the Communist Party. After dinner she rose and declared: “Mother, your fish is vile religious food. I will never eat it again!”

And that was it for the Brokhvis family’s Friday gefilte fish. Deep in her heart, Maria understood that the New Soviet Generation knew better.

I had no idea about any of this. Not the baby dead in the pogrom, not Grandma Liza’s ban on Maria’s religious food. Only when Mom and I were in her kitchen making our gefilte tribute to Maria did I find out.

Suddenly I understood why Grandma Liza had looked pensive and hesitant whenever she mentioned the dish. She too had run from her Jewishness back in Odessa. To her credit, Liza, who was blond and not remotely Semitic-looking, became enraged, proclaiming herself Jewish, if ever anyone made an anti-Semitic remark. Granddad Naum… not so much. About his family past Mom knows almost nothing—only that his people were shtetl Zionists and that Naum ran away from home as a teen, lied about his age to join the Red Army, and never looked back.

In Jackson Heights, Mom and I are both ecumenical culturalists. We light menorahs next to our Christmas trees. We bake Russian Easter kulich cake and make ersatz gefilte fish balls for Passover. But our gefilte fish this time was different—real Jewish food. We skinned a whole pike, hand-minced the flesh, cried grating the onion, sewed the fish mince inside the skin, and cooked the whole reconstituted beast for three hours.

The labor was vast, but for me it was a small way of atoning for that August day in Odessa.

Returning to twenties Bolshevik policies, I reflected again on how kitchen labor, particularly the kind at Maria’s politically equivocal NEP home canteen, got so little respect in the New Soviet vision. Partly this was pragmatic. Freeing women from the household pot was a matter of lofty principle, but it was also meant to push them into the larger workforce, perhaps even into the army of political agitators.

I haven’t mentioned her yet, this New Soviet Woman. Admittedly a lesser star than the New Soviet Man, she was still decidedly not a housewife-cook. She was a liberated proletarka (female proletarian)—co-builder of the road to utopia, co-defender of the Communist International, avid reader of Rabotnitsa (Female Worker), an enthusiastic participant in public life.

Not for her the domestic toil that “crushes and degrades women” (Lenin’s words). Not for her nursery drudgery, so “barbarously unproductive, petty, nerve-racking, stultifying” (Lenin again). No, under socialism, society would assume all such burdens, eventually eradicating the nuclear family. “The real emancipation of women, real communism, will begin,” predicted Lenin in 1919, “only where and when an all-out struggle begins… against… petty… housekeeping.”

In one of my favorite Soviet posters, a fierce New Soviet proletarka makes like a herald angel under the slogan DOWN WITH KITCHEN SLAVERY, rendered in striking avant-garde typography. She’s grinning down at an aproned female beleaguered by suds, dishes, laundry, and cobwebs. The red-clad proletarka opens wide a door to a light-flooded vision of New Soviet byt. Behold a multistoried Futurist edifice housing a public canteen, a kitchen-factory, and a nursery school, all crowned with a workers’ club.

The engine for turning such utopian Bolshevik feminist visions into reality was the Zhenotdel, literally “women’s department.” Founded in 1919 as an organ of the Party’s Central Committee, the Zhenotdel and its branches fought for—and helped win—crucial reforms in childcare, contraception, and marriage. They proselytized, recruited, and educated. The first head of Zhenotdel was the charismatic Inessa Armand—Paris-born, strikingly glamorous, and by many accounts more than simply a “comrade” to Lenin (Krupskaya being strikingly not glamorous). Ravaged by overwork, Armand died of cholera in 1920, desperately mourned by Vladimir Ilyich. The Zhenotdel mantle then passed to Alexandra Kollontai, who was perhaps too charismatic. Kollontai stands out as one of communism’s most dashing characters. A free-love apostle and scandalous practitioner of such (the likely model for Garbo’s Ninotchka), Kollontai essentially regarded the nuclear family as an inefficient use of labor, food, and fuel. Wife as homebody-cook outraged her.

“The separation of marriage from kitchen,” preached Kollontai, “is a reform no less important than the separation of church and state.”

In our family, we had our own Kollontai.

As Russian families go, mine represented a rich sampling of the pre-Soviet national pot. Mom’s people came from the Ukrainian shtetl. Dad’s paternal ancestors were Germanic aristocracy who married Caspian merchants’ daughters. And Dad’s mom, my extravagant and extravagantly beloved grandmother Alla, was raised by a fiery agitator for women’s rights in remote Central Asia.

When I was little, Alla cooked very infrequently, but when she bothered, she produced minor masterpieces. I particularly remember the stew my mom inherited from her and cooks to this day. It’s an Uzbek stew. A stew of burnished-brown lamb and potatoes enlivened with an angry dusting of paprika, crushed coriander seeds, and the faintly medicinal funk of zira, the Uzbek wild cumin. “From my childhood in Ferghana!” Alla would blurt over the dish, then add, “From a person very dear to me…” And then the subject was closed. But I knew whom she meant.

Alla Nikolaevna Aksentovich, my grandmother, was born a month before the October Revolution in what was still called Turkestan, as czarist maps labeled Central Asia. She was an out-of-wedlock baby, orphaned early and adopted by her maternal grandmother, Anna Alexeevna, who was a Bolshevik feminist in a very rough place to be one.

Turkestan. Muslim, scorchingly hot, vaster than modern India, much of it desert. One of the czars’ last colonial conquests, it was subjugated only in the 1860s. A decade later, Anna Alexeevna was born in the fertile Ferghana valley, Silk Road country from which the Russian Empire pumped cotton—as would the Soviet Empire, even more mercilessly. The lone photo we have of her, taken years later and elsewhere, shows Anna with a sturdy round Slavic face and high cheekbones. Her father was a Ural Cossack, definitely no supporter of Reds. In 1918, when she was already forty, a midwife by training, she defied him and joined the Communist Party. By 1924, she and little orphaned Alla were in Tashkent, the capital of the new republic of Uzbekistan. The Soviets by then had carved up Central Asia into five socialist “national” entities. Anna Alexeevna was the new deputy head of the “agitation” department of the Central Asian Bureau of the Central Committee.

There was much agitating to be done.

The civil war thereabouts had dragged on for extra years, Reds pitched against the basmachi (Muslim insurgents). With victory came—as elsewhere—staggering challenges. Unlike the Jews, Uzbeks weren’t easy converts to the Bolshevik cause. If Russia itself lacked the strict Marxian preconditions for communism—namely, advanced capitalism—agrarian former Turkestan, with its religious and clan structures, was downright feudal. How does one build socialism without a proletariat? The answer was women. Subjugated by husbands, clergy, and ruling chiefs, the women of Central Asia were “the most oppressed of the oppressed and the most enslaved of the enslaved,” as Lenin put it.

So the Soviets switched their rallying cry from class struggle and ethno-nationalism to gender. In the “women of the Orient” they found their “surrogate proletariat,” their battering ram for social and cultural change.

Anna Alexeevna and her fellow Zhenotdel missionaries toiled against the kalym (bride fee) and underage marriage, against polygamy and female seclusion and segregation. Most dramatically, they battled the most literal form of seclusion: the veil. In public Muslim women had to wear a paranji, a long, ponderous robe, and a chachvan, a veil. But veil sounds so flimsy. Imagine instead a massive, primeval head-to-knee shroud of horsehair, with no openings for eyes or mouth.

“The best revolutionary actions,” Kollontai reportedly once pronounced, “are pure drama.” Anna Alexeevna and the feminists had their coup de théâtre: The veil had to go! Few Soviet revolutionary actions were more sensational than the hujum (onslaught), the Central Asian campaign of unveiling.

March 8, 1927: International Women’s Day. In Uzbek cities veiled women go tramping en masse, escorted by police. Bands and native orchestras play. Stages set up on public squares swarm with flowers. There are fiery speeches by Zhenotdelki. Poems. Anna is on Tashkent’s main stage no doubt when the courageous first ones step up, pull off their horsehair mobile prisons, and fling them into bonfires. Thousands are inspired to do the same then and there—ten thousand veils are reportedly cast off on this day. Unveiled women surge through the streets shouting revolutionary slogans. Everyone sings. An astounding moment.

The backlash was wrathful and immediate.

Trapped between Lenin and Allah, Moscow and Mecca, the unveiled became social outcasts. Many redonned the paranji. Many others were raped and murdered by traditionalist males or their families, their mutilated bodies displayed in villages. Zhenotdel activists were threatened and killed. The firestorm lasted for years.

By decade’s end the radical theatrics of unveiling were abandoned. And all over the country the Zhenotdeli were being dismantled because Stalin pronounced the “women’s question” solved. By the midthirties, traditional family values were back, with divorce discouraged, abortions and homosexuality banned. On propaganda posters the Soviet Woman had a new look: maternal, full-figured, and “feminine.” And for the rest of the USSR’s existence, female comrades were expected to carry on their shoulders the infamous “double burden” of wage labor and housework.

And my great-great-grandmother, the New Soviet feminist?

In 1931 Anna Alexeevna moved with the teenage Alla to Moscow, to follow her boss Isaak Zelensky. A longtime Party stalwart, Zelensky was one of the engineers of War Communism’s grain requisitioning; he’d been brought back now to the capital from Central Asia to run the state’s consumer cooperatives. In 1937, in the midst of the purges, Zelensky was arrested. A year later he was in the dock with Bolshevik luminary Nikolai Bukharin at Stalin’s most notorious show trial. As ex-head of cooperative food suppliers, Zelensky breathtakingly “confessed” to sabotage, including the spoiling of fifty trainloads of eggs bound for Moscow, and the ruining of butter shipments by adding nails and glass.

He was promptly shot and deleted from Soviet history.

A year later my great-great-grandmother Anna was arrested as Zelensky’s co-conspirator and also deleted from history. From our family history, by my grandma Alla, who destroyed all photographs of her and stopped mentioning her name. Then one day, after the end of World War II, shaking with fear, Alla opened a letter from the gulag, from Kolyma in furthest Siberia. With blood-chilling precision, Anna Alexeevna had detailed the tortures she’d been subjected to and pleaded with the granddaughter she’d adopted and raised to inform Comrade Stalin. Like millions of victims, she was convinced the Supreme Leader knew nothing of the horrors going on in the prison camps. In my dad’s various retellings, Alla immediately burned the letter, flushed it down the communal apartment toilet, or ate it.

Only when drunk, very drunk, and much later, when I was a child, would Alla chase her shot glass of vodka with herring and crocodile tears and bellow how her grandma Anna Alexeevna had been stripped naked in minus-forty-degree weather, beaten in the cellars of the secret police’s Lubyanka Prison, kept from sleep for weeks. Then Dad would whisper to me the inheritance story. How Anna Alexeevna had been released in 1948 at the age of seventy, without a right of return to Moscow, and had lived in the Siberian city of Magadan. How Alla never visited her, not once. How Anna died in 1953, a few months before Stalin.

So imagine Alla’s surprise when in the mail arrived a death certificate; the photo of her grandmother, the only one that remains, taken in the gulag; and a money order for a whopping ten thousand rubles, most likely Anna Alexeevna’s hoardings from performing black market abortions in the prison camps.

Alla and Sergei burned through the inheritance at Moscow’s best restaurants. Alla favored the soaring dining room at the Moskva Hotel, fancying it for its green malachite columns and famously tender lamb riblets—and not, incidentally, because the mustachioed maestro of the gulags had liked to celebrate his birthdays there. Dad spent his gulag money at Aragvi, the Georgian hot spot on Gorky Street, again not because it was a favorite of Stalin’s last chief of secret police, Lavrenty Beria. It was just that the iron rings of Soviet life overlapped with all others.

With the rest of Anna Alexeevna’s rubles Alla bought a pair of suits for Sergei, which he wore for two decades. Also two blankets under which I slept when I stayed at Alla’s kommunalka near the mausoleum as a kid. They were wondrous blankets, one green, the other blue: feather-light and exquisitely silky-soft.

And there it was: two Chinese silk coverlets, two fancy suits, and a dish of Uzbek lamb—the only legacy of a Bolshevik feminist with her round, high-cheekboned Slavic face, a fierce crusader for women’s rights in the early days who helped in the assault, so dramatic, so ill-conceived, against the horsehair veil. And then disappeared.

The radical Bolshevik identity policies expanded rights for women, for Jews, for even the most obscure ethnic minorities, be they Buryat, Chuvash, or Karakalpak.

But one category of the disempowered got pushed off into the shadows of the Radiant Future, treated as an incorrigible menace. They happened to be 80 percent of the population, the ones feeding Russia. The peasants.

The “half-savage, stupid, ponderous people of the Russian villages,” as Maxim Gorky, village-born himself, called them in 1920.

“Avaricious, bloated, and bestial,” as Lenin termed them—specifically the kulaks, whose proportion was small, but whose name made an easily spread ideological tar.

The NEP offered a temporary lull in the ongoing conflict between town and country, but by the end of 1927, a full-blown grain crisis erupted once more.

Cue the cunning Georgian: Iosif Vissarionovich Dzhugashvili.

Stalin, as he was known (his Bolshevik pseudonym derived from “steel”), had since 1922 been the Party’s general secretary—a supposedly inconsequential post by which he’d maneuvered to be Lenin’s successor. (Trotsky, his chief rival, thought him slow-witted. It was brilliant, arrogant Trotsky, however, who was banished in 1929, and who had an ice ax driven into his skull in 1940.)

The 1927 grain crisis arose partly from fears of war—of an attack by Britain or some other vile capitalist power—that seized the country that year. Panic hoarding flared; peasants shied from selling grain to the state at low prices. Raising these prices might well have solved things. Instead, crying sabotage, the government turned again to repression and violence. On a notorious 1928 trip to Siberia, Stalin personally supervised coercive requisitioning. As his henchman Molotov later explained: “To survive, the State needed grain. Otherwise it would crack up. So we pumped away.”

The NEP market approach was effectively dead. About to replace it was Stalin’s final solution to the “peasant problem”—the problem of a reliable supply of cheap grain.

In 1929 the Soviet Union wrenched into Veliky Perelom (The Great Turn). As embodied in the first Five-Year Plan, this fantastically, fanatically ambitious project aimed to industrialize the country full throttle—at the expense of everything else. Long-backward Russia was to be transformed into “a country of metal, an automobilizing country, a tractorized country,” in Stalin’s booming phrases. Rationing reappeared, privileging industrial workers and leaving poorer peasants to fend for themselves.

The first thing to be rationed was bread. “The struggle for bread,” growled Stalin, with an echo of Lenin, “is the struggle for socialism.” Meaning the Soviet State would brook no more trouble from its 80 percent.

The furies of collectivization and “dekulakization” were unleashed now on the countryside. Up to ten million kulaks (that toxically elastic term) were thrown off their land, either killed or shipped to prison-labor settlements known after 1930 as the gulags, where great numbers died. The rest of the peasant households were forced onto kolkhozes (giant collective farms overseen by the state), from which the industrial engine could be dependably fed (or at least that was the idea). Peasants resisted this “second serfdom” by force, destroying their livestock on a catastrophic scale. By 1931 more than twelve million peasants had fled to the towns. In 1933 the country’s breadbasket, the fertile Ukraine, would plunge into man-made famine—one of the great tragedies of the twentieth century. Roads were blocked, peasants forbidden to leave, reports of the ongoing devastation suppressed. A dead peasant mother’s dribble of milk on her emaciated infant’s lips had a name: “the buds of the socialist spring.” Out of the estimated seven million who died in the Soviet famine, some three million perished in the Ukraine.

From these horrors Soviet agriculture would never recover.

By this point Lenin had been dead for almost ten years.

Dead—but not buried.

Following his long, mysterious illness (the “syphilis” whispers of many decades have lately reintrigued historians) Lenin expired in effective isolation on January 21, 1924. Stalin, a seminarian in his youth, understood the power of relics and was one of the early proponents of keeping the cadaver “alive.” At a 1923 Politburo session he’d already proposed that “contemporary science” offered a possibility of preserving the body, at least temporarily. Some Bolsheviks howled at the reek of deification. Krupskaya objected too, but nobody asked her.

From January 27 on, Lenin’s body lay in state at the unheated Hall of Columns in Moscow. The weather was so bitter that the palm trees laid on inside for the funeral froze. An icy fog hung over Red Square; mourners were treated for frostbite. But the cold helped preserve the “mournee” for a while.

The idea to replace the temporary embalmment with something eternal apparently arose spontaneously among the Funeral Commission—swiftly renamed the Immortalization Commission. Refrigeration was being mulled over, but as the weather warmed the body deteriorated, and the Commission panicked. Enter Boris Zbarsky, a self-promoting biochemist, and Vladimir Vorobyev, a gifted provincial pathologist. The pair proposed a radical embalming method. Miraculously, their wild gambit worked. Even a reluctant Krupskaya later told Zbarsky: “I’m getting older and he looks just the same.”

So the USSR had a New Soviet Eternal Man. Proof in the flesh that Soviet science could defeat even the grave. Socialist reshaping of humanity, it seemed, had soared beyond wildest imagining—far beyond a new everyday life. The antireligious Bolshevik of Bolsheviks, who had ordered clergy murdered and churches destroyed, was now a living relic, immortal in the manner of Orthodox saints.

From August 1924 on, the miraculous Object No. 1 (as it would later be code-named) preened for Red Square crowds inside a temporary wooden shrine created by the Constructivist architect Alexei Shchusev. Shchusev would go on to build the permanent mausoleum, the now iconic ziggurat of red, gray, and black stone the inner sanctum of which I was so desperate to penetrate as a child. The mavzoley was unveiled in 1930, but without particular fanfare. By then the USSR had a successor-God, one who was relegating Lenin to hazy Holy Spirit status.

Lenin, incidentally, transmigrated from this distant, idealized Spirithood into warm and fuzzy dedushka-hood during the Brezhnevian phase of his cult. That’s when the didactic cake stories became popular, along with that silly iconographic cap on his bald head—asserting Ilyich’s modest, friendly, proletarian nature.

The country would by then be wary of God-like personality cults.