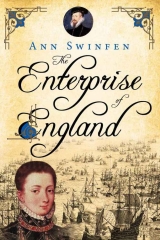

Текст книги "The Enterprise of England"

Автор книги: Ann Swinfen

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 5 (всего у книги 22 страниц)

I woke with a jerk and a shooting pain in my neck, as the door beside me was pushed open and four of the hospital servants carried in William Baker on his pallet, one to each corner. In the flickering light from the sconce on the wall above me, I could see that the leg was gone. William was in a dead swoon and the pallet was soaking with blood. I turned to Peter, who had followed them in. He was looking very green and his hands were shaking.

‘Peter, he must have fresh bedding. He cannot lie on that. Are there any more pallets to be had?’

‘I’ll see what I can find.’ He turned away, clearly glad of an excuse to escape.

‘And blankets,’ I said. ‘He will be cold from the shock. The mistress of the nurses should have some.’ Suddenly aware that it was not yet dawn, I added, ‘If she is still awake.’

‘I think I know where they are kept,’ he said. ‘If not, I will wake her.’

‘Brave man,’ I said, and he gave me a shaky smile.

‘I could dare anything, after that.’

‘Was it as bad as I suppose?’

‘Worse. I thought the poor bugger was going to die of the pain under our eyes.’

‘I gave him as much poppy as I dared.’

‘I know. I don’t think a barrelful would have helped. It was terrible, Kit.’

I nodded. ‘Once you have found some bedding and helped me make him comfortable, you should go to bed.’

‘Little point now,’ he said, gesturing towards the window, which had changed from black to the first lighter tinge of grey while we had been speaking.

The servants had deposited William in the empty space where he had lain before. There was nowhere else to put him. As soon as it was light I was determined to turn Goodman Watkins out of his bed and send him home, so William could have his bed. It would be too cruel to keep an amputee lying on the floor. I stood looking down at him. Unlike Andrew, he looked older, his face ashen with pain, the skin drawn tight over his cheekbones as though it had somehow shrunk. He had bitten his lips till they bled, so while I waited for Peter, I bathed his face and spread a little honey on his ravaged mouth. He did not even stir. It was the best thing for him. While the mind is deep asleep, the body can take its chance to mend itself.

When Peter returned, we struggled to lift William on to the clean pallet. The servants had retreated as soon as they had deposited him on the floor and there was very little room to move. In the end we managed to shift the men on either side a little way, so that we could lay the fresh pallet next to him. Then I took his shoulders and Peter – with nervous hesitation – took his remaining leg. We managed to lift him across. Then Peter removed the old pallet, which was so sodden it dripped blood along the floor as he carried it away. I tucked the two blankets around the soldier, taking care to avoid the stump, which had been cauterised and bound tightly to stop any further bleeding. Peter had even managed to find a small cushion, which I eased under William’s head. He moaned as I did so, and his eyelids fluttered, but did not open.

When I stood up, I saw that my father had returned with Peter and stood talking quietly to him near the door, so I went to join them.

‘Dr Stephens has gone home,’ my father said. ‘One of us at least should get some sleep.’

‘I’ve told Peter to do the same,’ I said. I turned to him. ‘You have a room in the hospital, don’t you?’

Peter was an orphan, with no family that he knew of. When he had come to St Bartholomew’s as a young servant, one of the licensed apothecaries, James Weatherby, had noticed his skill and intelligence, and took him on as an apprentice. I knew he had a room somewhere up in the attics.

‘Aye,’ he said, ‘but will I not be needed here?’

My father shook his head. ‘Master Weatherby is still here. He has said you may go.’

With that, Peter nodded to us and went off toward the staircase which led to the attics. Instead of his usual brisk step he plodded like an old man, hardly able to put one foot in front of another.

‘You should go home as well, Kit,’ my father said.

I shook my head. ‘I am so tired that I’m no longer tired. I feel like a swimmer come up for air.’

Even as I said it, I had a sudden flash of memory. My sister Isabel and my brother Felipe and I, swimming in the stream that ran beside the meadow at my grandfather’s solar, his estate in the foothills some miles above Coimbra. We used to dare each other to stay under water as long as we could, but we would pop up at last, breaking the surface like corks, gasping and laughing.

‘Caterina?’ My father was looking at me oddly, for I must have seemed far away.

‘Ssh!’ I said, glancing over my shoulder. There was no one near but the sleeping soldiers. That was twice tonight he had risked giving me away. Fatigue was making him incautious. ‘Be careful, Father.’

He passed a tired hand over his face. ‘I am sorry, Kit. It has been a long and weary night.’

‘It has. If anyone should go home, it is you.’

‘No, no. We will both stay on until Dr Stephens returns in the morning. Though I don’t think we will be needed. They are mostly asleep. Thomas Derby will be back in the morning.’

Thomas was Dr Stephens’s assistant, as I was my father’s. He had been away for three days, fetching a shipment of supplies from Dover.

‘I am going to watch over William Baker,’ I said.

‘Who?’ My father had not caught the name before.

‘The amputee. And there was that one soldier with the high fever, up at the top end of the ward. He may need more febrifuge tincture.’

‘Aye, you are right. I will sit up there, in case he wakes.’

Although the first fading of the night had shown in the window, the rest of the time seemed to drag sluggishly on to dawn. I found a stool which I could fit between the rows of men beside William Baker and sat there, willing myself to stay awake. I knew if I sat where I could lean against the wall, I would fall asleep again. Even so, several times my head fell forward till my chin hit my chest and a sharp stab in my spine woke me just as I drifted into sleep. I could make out my father dimly at the far end of the ward, seated, as I had been before, with his back propped against the wall. I hoped he would be able to doze a little, for he was showing his age, and was a little frail these days, however he tried to put on a brave face.

At last the long rectangles of the windows grew a paler grey, then gradually took on a tinge of pink, about the same time as I heard some of the town roosters beginning to greet the day. I wasn’t often awake as early as this. I could see, in the growing light, that my father was asleep. I was stiff with sitting so long on the hard stool, so I stood up and stretched, then slipped out of the ward and out of the hospital itself. In the courtyard the air smelled wonderfully fresh after the stench of so many sick and wounded bodies crowded together, and I drew in deep lungfuls of it. One of the hospital cats, kept to chase away any rats and mice from the storerooms, was washing himself in a pale yellow patch of morning sun, licking first one hind leg and then the other with meticulous care. Catching sight of me, he strolled over with the nonchalant benevolence of a monarch and rubbed against my leg. I tickled him behind the ears and was rewarded with a throaty rumble. When he stalked off on business of his own, I returned to the hospital, where the nursing sisters were just coming to take up their duties. Tonight we must make sure that some stayed in the wards over night, for the extra numbers we had taken in were going to need care and feeding.

When I reached the ward, I saw that my father was awake and so were some of the patients. Together, we got Goodman Watson out of his bed and dressed, and told him firmly that he was quite well enough to go home, despite his peevish protests. Then we sent for some of the men servants to lift William Baker into the vacated bed. He was still unconscious, but there was no bleeding from the stump of his leg. We could only pray that the surgeon had operated in time and that the gangrene would not spread any further.

The serving women brought porridge and small ale for the patients and we went round the ward, deciding whether any of the men were able to leave. Very few were well enough. Even those with less serious injuries were so weak from starvation that their recovery would be slow, so in the end we only sent three away, all of them with homes in London. When I came to Andrew, I saw that his fever had abated somewhat, but his skin was still dry and hot.

‘How do you find yourself this morning?’ I asked.

‘Better,’ he said. ‘Last night it felt as though a blacksmith was hammering on the inside of my skull. Now it’s just a tinsmith.’

He grinned at me and I smiled back. This was more like the old Andrew.

‘Well, once there’s only a sparrow pecking there, we’ll let you go home and try to grow your hair over that groove in your skull.’

‘Aye, I noticed you chopped away my locks last night.’

‘You wouldn’t want them sticking to the wound, I promise you. Where is your home?’

‘Gloucestershire. But I won’t go home, I’ll go back to my barracks in Dover.’

‘You won’t be fit for duty yet awhile.’

‘Tell my commander that.’

‘If it is the same commander as last year, he seemed a sensible man.’

‘No, he has been transferred to the Low Countries. We have a regular Tartar of a fellow now.’

‘Then we will send a letter with you, saying that you are not fit for work for another three weeks. Three weeks after we release you.’

‘You make the hospital sound like prison.’

‘You’d not be fed so well in any prison I’ve heard of. It is one of the provisions of Barts, to feed the patients well. Make the most of it. Here is your breakfast coming. I’m off home myself soon, but I will see you later today.’

He looked at me seriously for the first time. ‘I thank you for your care, Kit. You had a terrible night of it last night. How is that poor lad, William?’

I didn’t realise he had been aware of what had happened.

‘So far, he seems well enough. It’s a bad shock to the body, an amputation.’

‘It’s a fearful thing. The army will turn him away and forget that he lost his leg serving his country. It’s a cruel world out there for a one-legged man.’

‘I know. I am going to find his sister today and tell her what has happened.’ It was a task I was not looking forward to.

‘Well, it is good he has a sister. I hope she is a loving one.’ There was a touch of bitterness in his tone, but I did not probe him.

‘Eat your breakfast and then rest. Sleep is the best healer.’

‘It isn’t easy on this b’yer lady floor,’ he said, moving his shoulders irritably. I realised his dislocated shoulder would still be giving him pain, as well as the injury to his head.

‘I know, but we weren’t expecting four hundred extra patients. Now eat. I will come to see you later.’

Dr Stephens was talking to my father, who gestured to me that we should leave. I checked once more on William Baker, but he had not woken. However, his sleep seemed more natural now. I found myself yawning as if my jaw would break. Time to go home and to bed myself.

When I woke in my own bed I was momentarily confused by the broad swathe of light falling across the room. Then I remembered why I was still abed so late. I threw back the covers and rubbed my eyes. Although I had slept well, I still felt the exhaustion and horrors of the night before. I knew that when I returned to the hospital I would find that some of the soldiers had died while I was away, and others would be in a worse state than yesterday, not better.

I dressed slowly, my fingers fumbling with garters and buttons. Even in this warm summer weather I wore a doublet, for it was the best garment for concealing my shape and keeping up my pretence. I was still thin and flat-chested, though my breasts were beginning to swell. The time might come when I would need to bind them.

Down in the kitchen I found Joan on her knees, scrubbing the floor. She looked up at me, pushing a stray lock of hair out of her eyes.

‘Your father has gone this half hour, but he said I was to let you sleep. And he said you had some errand in Eastcheap, so not to go to the hospital until that was done. Dr Stephens’s assistant will have returned.’

‘Aye, thank you, Joan. Is there anything to eat?’

‘Bread and cheese and apples. Or do you want me to cook something?’ She looked pointedly around at the half of the floor not yet scrubbed.

‘No, no. This will suit.’

I picked my way over her bucket and brush. Putting a piece of cheese and two apples on a plate, and adding a chunk of bread which I spread with honey, I carried my breakfast outside and sat on the step to eat it, out of the way of her scrubbing. I was not looking forward to finding William Baker’s sister, but I had promised, so I must go.

The city was busy. Pushing along the roads, blocking the way for carters and the occasional horseman, the crowds were making the most of the late summer sun, shopping or gossiping. Apprentice boys in their blue tunics lounged in groups at street corners, as if they had no work to do. One man led a sad looking bear on a chain and stopped from time to time, playing on a pipe to make the creature dance. The poor beast had had his claws torn out and his coat was patched with mange. There were scars of old fights on his muzzle, so I guessed he was one of the old creatures from the bear pits. If they survive but become reluctant to put on a show, the owners will sell them off cheap. A bear keeper like this man would render the bear harmless by removing his claws and most of his teeth, then make him dance for a living. This one was unwilling. He rose up on his hind legs and shuffled his feet a few steps, then sank down on his haunches and refused to move. His keeper tucked his pipe in his waistband and began lashing the bear viciously with a whip, cursing him the while.

Most people simply walked past but I stopped and caught hold of the man’s whip arm. ‘I will give you a shilling if you will give me your whip and buy food for yourself and your animal.’

I could see that the man himself was gaunt with hunger and had a withered leg. He looked at me as if I were mad, his mouth hanging open. I don’t suppose anyone had ever given him more than a penny before. I held up two sixpenny pieces in one hand and reached out my other hand for the whip. Still gaping he grabbed the coins and bit them to be sure they were genuine.

‘The whip,’ I said.

He shrugged and handed it to me. I knew he would soon be able to get another, but at least they would both eat and the bear would be spared a whipping for the moment.

‘Be sure and feed the bear as well,’ I said.

‘Aye,’ he growled. ‘I’m no fool. He’s my livelihood.’

I left him staring at me as I walked away. The whip I snapped into four pieces and threw into the Fleet River.

There were three saddlers and leatherworking shops in Eastcheap. At the first one I was told that Jake Winterly’s shop was across the street and a hundred yards further on, at the sign of the Brown Bull and Scissors. I found the sign – a remarkably placid looking bull standing next to an enormous pair of scissors, as tall as he was. The door stood open, as did most doors in the street, to let in a little air on this hot day, and the counter was folded down from the front of the shop. Over the top I could see a woman and a small boy moving about inside, setting out a row of leather beer tankards along a shelf.

‘Mistress Winterly?’ I said as I walked in.

She turned and smiled at me, a plump, rosy-faced woman of about forty. The boy was about seven or eight and had the same yellow curls as William.

‘Aye, sir. That’s me. What can I do for you?’ She came forward, wiping her hands, which looked perfectly clean, on her apron.

There was no point weaving about the subject. Best to get it over with.

‘I am a doctor at St Bartholomew’s,’ I said. ‘Your brother, William Baker, was brought in yesterday.’

Her hand flew to her mouth to stifle a faint cry and she sank down on a bench.

‘Was he one of those at Sluys, sir? We couldn’t be sure. Last we heard, he was posted to Dover. He’s a poor hand at writing letters.’

‘I don’t suppose many letters made their way out of Sluys,’ I said, ‘except official despatches slipped out by a few brave messengers. Aye, he’s one of the survivors.’

‘Oh, Jesu be praised!’ She had gone quite white. Now her face flushed again. ‘Will, go and fetch your father.’

The boy ran to a curtain which covered the door to the back shop and slipped through.

‘Please, sir, take a seat. I’ve been that worried, not knowing whether he had been sent with those men to the Low Countries, or whether he was in that terrible siege. Is he hurt?’

I sat down on a three-legged stool facing her. ‘I think all of those who survived were hurt. They made a brave stand to the very end.’ I was more reluctant than ever to break the news.

‘William was always determined to be a soldier. Our father was a saddler, and Jake – that’s my man – was his journeyman. We wanted William to stay in the business, but there was nothing for it but he must become a soldier. He said that way he would see the world. He couldn’t go for a sailor, for he’d be sick just in a wherry crossing the Thames.’ She gave an indulgent sister’s chuckle. ‘And then, after all, he’s spent most of his time guarding the Tower or down at Dover castle. I don’t suppose he saw much of the world down in Kent.’

She seemed to have forgotten her question in her memories of her brother, and I was uncertain how to answer it now, but at that moment a big man pushed the curtain aside and stepped into the shop. Like his wife he was at least fifteen years older than William Baker, his hair already grizzled at the temples. I noticed that his hands were stained from the leather dyes. I stood up and made a slight bow.

‘Master Winterly? I am Christoval Alvarez, a physician at St Bartholomew’s. I have brought word of your brother-in-law.’

He bowed his head, then moved swiftly to his wife’s side and laid his hand on her shoulder.

‘He’s one of the men from Sluys?’ he said. ‘I saw them being carried off the ship yesterday. How bad is William?’

I swallowed. ‘His leg had been smashed by a Spanish cannon ball several weeks ago. I don’t suppose they had much medical care in the garrison. When I saw him last night, he had developed gangrene.’

The woman pressed both hands to her mouth and tears welled up in her eyes.

‘Is he dead?’ The man’s tone was not abrupt. I could see that he just needed to know the worst, without any more hesitation.

‘We had to amputate,’ I said. ‘We fetched the best surgeon in London. Master Hawkins. He thinks it is clean now, and when I left the hospital early this morning, William was sleeping peacefully. But I am sure you understand. Until the leg has healed, we cannot be sure the gangrene will not return.’

The woman was weeping openly now, but silently, covering her face with her apron. I saw her husband tighten his grip on her shoulder. The child had slipped behind her and was looking first at his father and then at me.

The man cleared his throat. ‘So he will be crippled. The army will throw him out.’

‘Aye.’ I wasn’t prepared to lie to these people. I could see that they wanted the truth. ‘Otherwise, he is unharmed. If he recovers, as I hope he will, he will be able to get about on crutches, but certainly he can no longer be a soldier.’

I left it hanging in the air. The woman lifted her tear stained face from her apron and looked up at her husband. Neither said anything, but he gave a small nod.

‘William will come here,’ he said, ‘once he is able to leave the hospital. There is plenty of work that he can do. The navy is needing ale jacks and scabbards and quivers and the Saints only know what else.’

‘Uncle William can share your room, Will,’ the woman said, ‘and he can tell you all about his adventures. Won’t that be grand?’

The child nodded solemnly, then suddenly grinned. I realised that the family probably lived in the cramped quarters above the shop, but their warmth warmed me and I suddenly felt a flood of relief. This had not been quite the ordeal I had dreaded. I stood up.

‘If you would like to visit, William,’ I said, ‘I think it would do him good.’ I was sure the knowledge that he would have a home and an occupation, to come to when he left the hospital, would help him recover as much as anything I could do.

‘I’ll come now!’ The woman sprang to her feet and rubbed her face dry on her apron. ‘Will, you must mind the shop for Mama – can you so that?’

The child, flushed with pride, nodded.

‘Are you going back to the hospital now, Doctor? May I walk with you?’

‘Certainly.’

As she took off her apron and fetched her hat from a hook at the back of the shop, I turned to her husband. ‘Thank you, Master Winterly,’ I said, barely above a whisper. ‘That is the best medicine I can bring him. He is near despair.’

‘He need not despair.’ His voice was as soft as mine. ‘There will always be a home for him here.’

Mistress Winterly and I crossed the city together, saying little. In her anxiety to see her brother she walked hurriedly, almost breaking into a run from time to time, then, recalling herself, slowed down again.

‘Forgive me, Doctor,’ she said. ‘I am afraid that, if I don’t hurry . . .’

‘Nothing to forgive,’ I said. ‘But do not be afraid. There was no sign of the gangrene this morning. I am sure he will be alive when we get there.’

I hoped I was speaking the truth. Sometimes it can happen, after a very severe injury, or an amputation, that a patient may simply die of shock. It is as if the heart cannot endure any more. But William was young and, apart from his injury and the privations of the siege, he was probably strong enough. Yet sometimes, too, a mind full of despair can end a man’s life, if he no longer wants to live.

The ward was not much changed from last night, though several of the regular patients had been sent home and the most badly injured of the soldiers moved into their beds. There was a little more space between the pallets on the floor. Clearly the mistress of the nursing sisters had stood firm against any women of the neighbourhood being allowed near the patients, but some of the sewing women were assisting and the women servants were just clearing away the midday meal.

I led Mistress Winterly over to William’s bed. To my relief, he was still there. I had feared we might find him dead already. He lay quite still, his eyes closed, his face very pale. When I laid my hand on his brow I could find no trace of fever, which augured well. I fetched a stool and placed it beside the bed.

‘Sit here,’ I said. ‘Take care not to lean on the bed. He will still be feeling much pain.’

Dr Stephens’s assistant, Thomas Derby, came across to us.

‘How is he faring, Thomas?’ I asked.

‘Quiet. No sign of fever yet.’ He glanced at Mistress Winterly and raised his eyebrows in question.

‘This is his sister, come to see him.’

‘I doubt if he will wake.’

At that moment William stirred and gave a soft moan. I leaned over him. His breathing was regular, but a look of agony passed over his face like a wave and his eyes opened. He stared at me until his eyes focused.

‘Doctor?’

‘You are doing well, William. And see, I have brought your sister to see you. She has much to tell you.’

As we had walked, I had warned her not to weep over him, if she could forebear. I saw now with what courage she smiled cheerfully.

‘Well, William, how good it is to see you at last! You are to come to us when you leave the hospital. Jake needs your help, for we are quite overwhelmed with business. So you see, you must get well, for our sake. I do not know how we can manage without you.’

I saw an incredulous look come over William’s face and he reached out to take his sister’s hand. I jerked my head at Thomas and we retreated.

‘That is one fellow who is likely to recover,’ he said. ‘That’s a brave woman. Does she know?’

‘Aye, she knows.’

I went the rounds of my more seriously injured patients. The young boy with the crushed hand was in a high fever, but I managed to dribble some of the febrifuge tincture into his mouth, although he thrashed about and spilt much of it. The hand was still very inflamed, so I salved it again, but did not remove the splints I had fixed the night before. They were still in place and were best not disturbed. He had been moved to a bed and next to him was Andrew.

‘And how do you find yourself today?’ I said, perched on the edge of his bed and unwinding the dressing on his head. It was a relief not to have to kneel on the floor to do it.

‘Still the tinsmiths in here,’ he said, tapping the uninjured side of his head. ‘Ouch, Kit, don’t tear my scalp off as well!’

‘Don’t squall like an infant,’ I said. I leaned over and sniffed the long gouge that ran above his ear. ‘No nasty smells, you’ll be glad to know. The ear is healing already. And the rest is beginning to dry up. It looks better than it did yesterday, even in this bright sunlight. You’ll live.’

‘That’s good to know. So I’ll soon be fit to be sent back to the Low Countries.’

I looked at him soberly as I rebandaged his head. ‘Is that what will happen, do you think?’

He shrugged, and winced at the pain in his shoulder. ‘Either that or fighting the Spanish at sea. Everything depends on what King Philip intends.’

‘Aye. Well, Drake has bought us some time.’

‘They will come some time next year,’ he said with conviction. ‘That is why they wanted to take Sluys. Parma is establishing his bases all along the coast of the Low Countries, facing us across the Channel. I believe they will send their army across from there, while the Spanish navy comes up from the west. Snipping us like a pair of shears.’

I nodded. ‘That is what Walsingham believes as well. And he says we must defeat them at sea.’

Andrew nodded, then regretted it and put a hand to his brow. ‘I forgot. I must not do that. Aye, your master is right. On land we have no hope. We trained soldiers are so few.’ He cast a look around at the patients lying on the floor. ‘A thousand fewer now. No, our only hope is our navy.’

‘And will you be posted on shore?’ I asked.

‘Oh, no. We will be aboard the ships, ready to fight if we can board theirs, though I expect most of the fighting will be a cannon shot apart. We’ll use our archers, of course, both to attack their crews and to shoot fire arrows. The rest of us have our muskets.’

I shivered. ‘And then it will be left to us to put you all back together again.’

He gave a grim smile. ‘Let us hope we both survive long enough to do just that.’