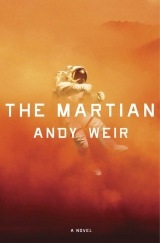

Текст книги "The Martian"

Автор книги: Andy Weir

Жанры:

Научная фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 13 (всего у книги 22 страниц)

“A near-Earth rendezvous with Hermes is more doable?” Teddy asked.

“Much more doable,” Venkat confirmed. “With sub-second transmission delays, we can control the probe directly from Earth rather than rely on automated systems. When the time comes to dock, Major Martinez can pilot it remotely from Hermes with no transmission delay at all. And Hermes has a human crew, able to overcome any hiccups that may happen. And we don’t have to do a reentry; the supplies don’t have to survive a three-hundred-meters-per-second impact.”

“So,” Bruce offered, “we can have a high chance of killing one person, or a low chance of killing six people. Jeez. How do we even make this decision?”

“We talk about it, then Teddy makes the decision,” Venkat said. “Not sure what else we can do.”

“We could let Lewis—” Mitch began.

“Yeah, other than that,” Venkat interrupted.

“Question,” Annie said. “What am I even here for? This seems like something for you nerds to discuss.”

“You need to be in the loop,” Venkat said. “We’re not deciding right now. We’ll need to quietly research the details internally. Something might leak, and you need to be ready to dance around questions.”

“How long have we got to make a decision?” Teddy asked.

“The window for starting the maneuver ends in thirty-nine hours.”

“All right,” Teddy said. “Everyone, we discuss this only in person or on the phone; never e-mail. And don’t talk to anyone about this, other than the people here. The last thing we need is public opinion pressing for a risky cowboy rescue that may be impossible.”

•••

Beck:

Hey, man. How ya been?

Now that I’m in a “dire situation,” I don’t have to follow social rules anymore. I can be honest with everyone.

Bearing that in mind, I have to say…dude…you need to tell Johanssen how you feel. If you don’t, you’ll regret it forever.

I won’t lie: It could end badly. I have no idea what she thinks of you. Or of anything. She’s weird.

But wait till the mission’s over. You’re on a ship with her for another two months. Also, if you guys got up to anything while the mission was in progress, Lewis would kill you.

•••

VENKAT, MITCH, Annie, Bruce, and Teddy met for the second time in as many days. “Project Elrond” had taken on a dark connotation throughout the Space Center, veiled in secrecy. Many people knew the name, none knew its purpose.

Speculation ran rampant. Some thought it was a completely new program in the works. Others worried it might be a move to cancel Ares 4 and 5. Most thought it was Ares 6 in the works.

“It wasn’t an easy decision,” Teddy said to the assembled elite. “But I’ve decided to go with Iris 2. No Rich Purnell Maneuver.”

Mitch slammed his fist on the table.

“We’ll do all we can to make it work,” Bruce said.

“If it’s not too much to ask,” Venkat began, “what made up your mind?”

Teddy sighed. “It’s a matter of risk,” he said. “Iris 2 only risks one life. Rich Purnell risks all six of them. I know Rich Purnell is more likely to work, but I don’t think it’s six times more likely.”

“You coward,” Mitch said.

“Mitch…,” Venkat said.

“You god damned coward,” Mitch continued, ignoring Venkat. “You just want to cut your losses. You’re on damage control. You don’t give a shit about Watney’s life.”

“Of course I do,” Teddy replied. “And I’m sick of your infantile attitude. You can throw all the tantrums you want, but the rest of us have to be adults. This isn’t a TV show; the riskier solution isn’t always the best.”

“Space is dangerous,” Mitch snapped. “It’s what we do here. If you want to play it safe all the time, go join an insurance company. And by the way, it’s not even your life you’re risking. The crew can make up their own minds about it.”

“No, they can’t,” Teddy fired back. “They’re too emotionally involved. Clearly, so are you. I’m not gambling five additional lives to save one. Especially when we might save him without risking them at all.”

“Bullshit!” Mitch shot back as he stood from his chair. “You’re just convincing yourself the crash-lander will work so you don’t have to take a risk. You’re hanging him out to dry, you chickenshit son of a bitch!”

He stormed out of the room, slamming the door behind him.

After a few seconds, Venkat followed behind, saying, “I’ll make sure he cools off.”

Bruce slumped in his chair. “Sheesh,” he said nervously. “We’re scientists, for Christ’s sake. What the hell!?”

Annie quietly gathered her things and placed them in her briefcase.

Teddy looked to her. “Sorry about that, Annie,” he said. “What can I say? Sometimes men let testosterone take over—”

“I was hoping he’d kick your ass,” she interrupted.

“What?”

“I know you care about the astronauts, but he’s right. You are a fucking coward. If you had balls, we might be able to save Watney.”

•••

Lewis:

Hi, Commander.

Between training and our trip to Mars, I spent two years working with you. I think I know you pretty well. So I’m guessing you still blame yourself for my situation, despite my earlier e-mail asking you not to.

You were faced with an impossible scenario and made a tough decision. That’s what commanders do. And your decision was right. If you’d waited any longer, the MAV would have tipped.

I’m sure you’ve run through all the possible outcomes in your head, so you know there’s nothing you could have done differently (other than “be psychic”).

You probably think losing a crewman is the worst thing that can happen. Not true. Losing the whole crew is worse. You kept that from happening.

But there’s something more important we need to discuss: What is it with you and disco? I can understand the ’70s TV because everyone loves hairy people with huge collars. But disco?

Disco!?

•••

VOGEL CHECKED the position and orientation of Hermes against the projected path. It matched, as usual. In addition to being the mission’s chemist, he was also an accomplished astrophysicist. Though his duties as navigator were laughably easy.

The computer knew the course. It knew when to angle the ship so the ion engines would be aimed correctly. And it knew the location of the ship at all times (easily calculated from the position of the sun and Earth, and knowing the exact time from an on-board atomic clock).

Barring a complete computer failure or other critical event, Vogel’s vast knowledge of astrodynamics would never come into play.

After completing the check, he ran a diagnostic on the engines. They were functioning at peak. He did all this from his quarters. All onboard computers could control all ships’ functions. Gone were the days of physically visiting the engines to check up on them.

Having completed his work for the day, he finally had time to read e-mail.

Sorting through the messages NASA deemed worthy to upload, he read the most interesting first and responded when necessary. His responses were cached and would be sent to Earth with Johanssen’s next uplink.

A message from his wife caught his attention. Titled “unsere kinder” (“our children”), it contained nothing but an image attachment. He raised an eyebrow. Several things stood out at once. First, “kinder” should have been capitalized. Helena, a grammar school teacher in Bremen, was very unlikely to make that mistake. Also, to each other, they affectionately called their kids die Affen.

When he tried to open the image, his viewer reported that the file was unreadable.

He walked down the narrow hallway. The crew quarters stood against the outer hull of the constantly spinning ship to maximize simulated gravity. Johanssen’s door was open, as usual.

“Johanssen. Good evening,” Vogel said. The crew kept the same sleep schedule, and it was nearing bedtime.

“Oh, hello,” Johanssen said, looking up from her computer.

“I have the computer problem,” Vogel explained. “I wonder if you will help.”

“Sure,” she said.

“You are in the personal time,” Vogel said. “Perhaps tomorrow when you are on the duty is better?”

“Now’s fine,” she said. “What’s wrong?”

“It is a file. It is an image, but my computer cannot view.”

“Where’s the file?” she asked, typing on her keyboard.

“It is on my shared space. The name is ‘kinder.jpg.’”

“Let’s take a look,” she said.

Her fingers flew over her keyboard as windows opened and closed on her screen. “Definitely a bad jpg header,” she said. “Probably mangled in the download. Lemme look with a hex editor, see if we got anything at all.…”

After a few moments she said, “This isn’t a jpeg. It’s a plain ASCII text file. Looks like…well, I don’t know what it is. Looks like a bunch of math formulae.” She gestured to the screen. “Does any of this make sense to you?”

Vogel leaned in, looking at the text. “Ja,” he said. “It is a course maneuver for Hermes. It says the name is ‘Rich Purnell Maneuver.’”

“What’s that?” Johanssen asked.

“I have not heard of this maneuver.” He looked at the tables. “It is complicated…very complicated.…”

He froze. “Sol 549!?” he exclaimed. “Mein Gott!”

•••

THE HERMES crew enjoyed their scant personal time in an area called “the Rec.” Consisting of a table and barely room to seat six, it ranked low in gravity priority. Its position amidships granted it a mere 0.2 g.

Still, it was enough to keep everyone in a seat as they pondered what Vogel told them.

“…and then mission would conclude with Earth intercept two hundred and eleven days later,” he finished up.

“Thank you, Vogel,” Lewis said. She’d heard the explanation earlier when Vogel came to her, but Johanssen, Martinez, and Beck were hearing it for the first time. She gave them a moment to digest.

“Would this really work?” Martinez asked.

“Ja.” Vogel nodded. “I ran the numbers. They all check out. It is brilliant course. Amazing.”

“How would he get off Mars?” Martinez asked.

Lewis leaned forward. “There was more in the message,” she began. “We’d have to pick up a supply near Earth, and he’d have to get to Ares 4’s MAV.”

“Why all the cloak and dagger?” Beck asked.

“According to the message,” Lewis explained, “NASA rejected the idea. They’d rather take a big risk on Watney than a small risk on all of us. Whoever snuck it into Vogel’s e-mail obviously disagreed.”

“So,” Martinez said, “we’re talking about going directly against NASA’s decision?”

“Yes,” Lewis confirmed, “that’s exactly what we’re talking about. If we go through with the maneuver, they’ll have to send the supply ship or we’ll die. We have the opportunity to force their hand.”

“Are we going to do it?” Johanssen asked.

They all looked to Lewis.

“I won’t lie,” she said. “I’d sure as hell like to. But this isn’t a normal decision. This is something NASA expressly rejected. We’re talking about mutiny. And that’s not a word I throw around lightly.”

She stood and paced slowly around the table. “We’ll only do it if we all agree. And before you answer, consider the consequences. If we mess up the supply rendezvous, we die. If we mess up the Earth gravity assist, we die.

“If we do everything perfectly, we add five hundred and thirty-three days to our mission. Five hundred and thirty-three days of unplanned space travel where anything could go wrong. Maintenance will be a hassle. Something might break that we can’t fix. If it’s life-critical, we die.”

“Sign me up!” Martinez smiled.

“Easy, cowboy,” Lewis said. “You and I are military. There’s a good chance we’d be court-martialed when we got home. As for the rest of you, I guarantee they’ll never send you up again.”

Martinez leaned against the wall, arms folded with a half grin on his face. The rest silently considered what their commander had said.

“If we do this,” Vogel said, “it would be over one thousand days of space. This is enough space for a life. I do not need to return.”

“Sounds like Vogel’s in,” Martinez grinned. “Me, too, obviously.”

“Let’s do it,” Beck said.

“If you think it’ll work,” Johanssen said to Lewis, “I trust you.”

“Okay,” Lewis said. “If we go for it, what’s involved?”

Vogel shrugged. “I plot the course and execute it,” he said. “What else?”

“Remote override,” Johanssen said. “It’s designed to get the ship back if we all die or something. They can take over Hermes from Mission Control.”

“But we’re right here,” Lewis said. “We can undo whatever they try, right?”

“Not really,” Johanssen said. “Remote override takes priority over any onboard controls. It assumes there’s been a disaster and the ship’s control panels can’t be trusted.”

“Can you disable it?” Lewis asked.

“Hmm…” Johanssen pondered. “Hermes has four redundant flight computers, each connected to three redundant comm systems. If any computer gets a signal from any comm system, Mission Control can take over. We can’t shut down the comms; we’d lose telemetry and guidance. We can’t shut down the computers; we need them to control the ship. I’ll have to disable the remote override on each system.… It’s part of the OS; I’ll have to jump over the code.… Yes. I can do it.”

“You’re sure?” Lewis asked. “You can turn it off?”

“Shouldn’t be hard,” Johanssen said. “It’s an emergency feature, not a security program. It isn’t protected against malicious code.”

“Malicious code?” Beck smiled. “So…you’ll be a hacker?”

“Yeah.” Johanssen smiled back. “I guess I will.”

“All right,” Lewis said. “Looks like we can do it. But I don’t want peer pressure forcing anyone into it. We’ll wait for twenty-four hours. During that time, anyone can change their mind. Just talk to me in private or send me an e-mail. I’ll call it off and never tell anyone who it was.”

Lewis stayed behind as the rest filed out. Watching them leave, she saw they were smiling. All four of them. For the first time since leaving Mars, they were back to their old selves. She knew right then no one’s mind would change.

They were going back to Mars.

•••

EVERYONE KNEW Brendan Hutch would be running missions soon.

He’d risen through NASA’s ranks as fast as one could in the large, inertia-bound organization. He was known as a diligent worker, and his skill and leadership qualities were plain to all his subordinates.

Brendan was in charge of Mission Control from one a.m. to nine a.m. every night. Continued excellent performance in this role would certainly net him a promotion. It had already been announced he’d be backup flight controller for Ares 4, and he had a good shot at the top job for Ares 5.

“Flight, CAPCOM,” a voice said through his headset.

“Go, CAPCOM,” Brendan responded. Though they were in the same room, radio protocol was observed at all times.

“Unscheduled status update from Hermes.”

With Hermes ninety light-seconds away, back-and-forth voice communication was impractical. Other than media relations, Hermes would communicate via text until they were much closer.

“Roger,” Brendan said. “Read it out.”

“I…I don’t get it, Flight,” came the confused reply. “No real status, just a single sentence.”

“What’s it say?”

“Message reads: ‘Houston, be advised: Rich Purnell is a steely-eyed missile man.’”

“What?” Brendan asked. “Who the hell is Rich Purnell?”

“Flight, Telemetry,” another voice said.

“Go, Telemetry,” Brendan said.

“Hermes is off course.”

“CAPCOM, advise Hermes they’re drifting. Telemetry, get a correction vector ready—”

“Negative, Flight,” Telemetry interrupted. “It’s not drift. They adjusted course. Instrumentation uplink shows a deliberate 27.812– degree rotation.”

“What the hell?” Brendan stammered. “CAPCOM, ask them what the hell.”

“Roger, Flight…message sent. Minimum reply time three minutes, four seconds.”

“Telemetry, any chance this is instrumentation failure?”

“Negative, Flight. We’re tracking them with SatCon. Observed position is consistent with the course change.”

“CAPCOM, read your logs and see what the previous shift did. See if a massive course change was ordered and somehow nobody told us.”

“Roger, Flight.”

“Guidance, Flight,” Brendan said.

“Go, Flight,” was the reply from the guidance controller.

“Work out how long they can stay on this course before it’s irreversible. At what point will they no longer be able to intercept Earth?”

“Working on that now, Flight.”

“And somebody find out who the hell Rich Purnell is!”

•••

MITCH PLOPPED down on the couch in Teddy’s office. He put his feet up on the coffee table and smiled at Teddy. “You wanted to see me?”

“Why’d you do it, Mitch?” Teddy demanded.

“Do what?”

“You know damn well what I’m talking about.”

“Oh, you mean the Hermes mutiny?” Mitch said innocently. “You know, that’d make a good movie title. The Hermes Mutiny. Got a nice ring to it.”

“We know you did it,” Teddy said sternly. “We don’t know how, but we know you sent them the maneuver.”

“So you don’t have any proof.”

Teddy glared. “No. Not yet, but we’re working on it.”

“Really?” Mitch said. “Is that really the best use of our time? I mean, we have a near-Earth resupply to plan, not to mention figuring out how to get Watney to Schiaparelli. We’ve got a lot on our plates.”

“You’re damn right we have a lot on our plates!” Teddy fumed. “After your little stunt, we’re committed to this thing.”

“Alleged stunt,” Mitch said, raising a finger. “I suppose Annie will tell the media we decided to try this risky maneuver? And she’ll leave out the mutiny part?”

“Of course,” Teddy said. “Otherwise we’d look like idiots.”

“I guess everyone’s off the hook then!” Mitch smiled. “Can’t fire people for enacting NASA policy. Even Lewis is fine. What mutiny? And maybe Watney gets to live. Happy endings all around!”

“You may have killed the whole crew,” Teddy countered. “Ever think of that?”

“Whoever gave them the maneuver,” Mitch said, “only passed along information. Lewis made the decision to act on it. If she let emotion cloud her judgment, she’d be a shitty commander. And she’s not a shitty commander.”

“If I can ever prove it was you, I’ll find a way to fire you for it,” Teddy warned.

“Sure.” Mitch shrugged. “But if I wasn’t willing to take risks to save lives, I’d…” He thought for a moment. “Well, I guess I’d be you.”

CHAPTER 17

LOG ENTRY: SOL 192

Holy shit!

They’re coming back for me!

I don’t even know how to react. I’m choked up!

And I’ve got a shitload of work to do before I catch that bus home.

They can’t orbit. If I’m not in space when they pass by, all they can do is wave.

I have to get to Ares 4’s MAV. Even NASA accepts that. And when the nannies at NASA recommend a 3200-kilometer overland drive, you know you’re in trouble.

Schiaparelli, here I come!

Well…not right away. I still have to do the aforementioned shitload of work.

My trip to Pathfinder was a quick jaunt compared to the epic journey that’s coming up. I got away with a lot of shortcuts because I only had to survive eighteen sols. This time, things are different.

I averaged 80 kilometers per sol on my way to Pathfinder. If I do that well toward Schiaparelli, the trip’ll take forty sols. Call it fifty to be safe.

But there’s more to it than just travel. Once I get there, I’ll need to set up camp and do a bunch of MAV modifications. NASA estimates they’ll take thirty sols, forty-five to be safe. Between the trip and the MAV mods, that’s ninety-five sols. Call it one hundred because ninety-five cries out to be approximated.

So I’ll need to survive away from the Hab for a hundred sols.

“What about the MAV?” I hear you ask (in my fevered imagination). “Won’t it have some supplies? Air and water at the very least?”

Nope. It’s got dick-all.

It does have air tanks, but they’re empty. An Ares mission needs lots of O2, N2, and water anyway. Why send more with the MAV? Easier to have the crew top off the MAV from the Hab. Fortunately for my crewmates, the mission plan had Martinez fill the MAV tanks on Sol 1.

The flyby is on Sol 549, so I’ll need to leave by 449. That gives me 257 sols to get my ass in gear.

Seems like a long time, doesn’t it?

In that time, I need to modify the rover to carry the “Big Three”: the atmospheric regulator, the oxygenator, and the water reclaimer. All three need to be in the pressurized area, but the rover isn’t big enough. All three need to be running at all times, but the rover’s batteries can’t handle that load for long.

The rover will also need to carry all my food, water, and solar cells, my extra battery, my tools, some spare parts, and Pathfinder. As my sole means of communication with NASA, Pathfinder gets to ride on the roof, Granny Clampett style.

I have a lot of problems to solve, but I have a lot of smart people to solve them. Pretty much the whole planet Earth.

NASA is still working on the details, but the idea is to use both rovers. One to drive around, the other to act as my cargo trailer.

I’ll have to make structural changes to that trailer. And by “structural changes” I mean “cut a big hole in the hull.” Then I can move the Big Three in and use Hab canvas to loosely cover the hole. It’ll balloon out when I pressurize the rover, but it’ll hold. How will I cut a big chunk out of a rover’s hull? I’ll let my lovely assistant Venkat Kapoor explain further:

[14:38] JPL: I’m sure you’re wondering how to cut a hole in the rover.

Our experiments show a rock sample drill can get through the hull. Wear and tear on the bit is minimal (rocks are harder than carbon composite). You can cut holes in a line, then chisel out the remaining chunks between them.

I hope you like drilling. The drill bit is 1 cm wide, the holes will be 0.5 cm apart, and the length of the total cut is 11.4 m. That’s 760 holes. And each one takes 160 seconds to drill.

Problem: The drills weren’t designed for construction projects. They were intended for quick rock samples. The batteries only last 240 seconds. You do have two drills, but you’d still only get 3 holes done before needing to recharge. And recharging takes 41 minutes.

That’s 173 hours of work, limited to 8 EVA hours per day. That’s 21 days of drilling, and that’s just too long. All our other ideas hinge on this cut working. If it doesn’t, we need time to come up with new ones.

So we want you to wire a drill directly to Hab power.

The drill expects 28.8 V and pulls 9 amps. The only lines that can handle that are the rover recharge lines. They’re 36 V, 10 amp max. Since you have two, we’re comfortable with you modifying one.

We’ll send you instructions on how to step down the voltage and put a new breaker in the line, but I’m sure you already know how.

I’ll be playing with high-voltage power tomorrow. Can’t imagine anything going wrong with that!

LOG ENTRY: SOL 193

I managed to not kill myself today, even though I was working with high voltage. Well, it’s not as exciting as all that. I disconnected the line first.

As instructed, I turned a rover charging cable into a drill power source. Getting the voltage right was a simple matter of adding resistors, which my electronics kit has in abundance.

I had to make my own nine-amp breaker. I strung three three-amp breakers in parallel. There’s no way for nine amps to get through that without tripping all three in rapid succession.

Then I had to rewire a drill. Pretty much the same thing I did with Pathfinder. Take out the battery and replace it with a power line from the Hab. But this time it was a lot easier.

Pathfinder was too big to fit through any of my airlocks, so I had to do all the rewiring outside. Ever done electronics while wearing a space suit? Pain in the ass. I even had to make a workbench out of MAV landing struts, remember?

Anyway, the drill fit in the airlock easily. It’s only a meter tall, and shaped like a jackhammer. We did our rock sampling standing up, like Apollo astronauts.

Also, unlike my Pathfinder hatchet job, I had the full schematics of the drill. I removed the battery and attached a power line where it used to be. Then, taking the drill and its new cord outside, I connected it to the modified rover charger and fired it up.

Worked like a charm! The drill whirled away with happy abandon. Somehow, I had managed to do everything right the first try. Deep down, I thought I’d fry the drill for sure.

It wasn’t even midday yet. I figured why not get a jump on drilling?

[10:07] Watney: Power line modifications complete. Hooked it up to a drill, and it works great. Plenty of daylight left. Send me a description of that hole you want me to cut.

[10:25] JPL: Glad to hear it. Starting on the cut sounds great. Just to be clear, these are modifications to Rover 1, which we’ve been calling “the trailer.” Rover 2 (the one with your modifications for the trip to Pathfinder) should remain as is for now.

You’ll be taking a chunk out of the roof, just in front of the airlock in the rear of the vehicle. The hole needs to be at least 2.5 m long and the full 2 m width of the pressure vessel.

Before any cuts, draw the shape on the trailer, and position the trailer where Pathfinder’s camera can see it. We’ll let you know if you got it right.

[10:43] Watney: Roger. Take a pic at 11:30, if you haven’t heard from me by then.

The rovers are made to interlock so one can tow the other. That way you can rescue your crewmates if all hell breaks loose. For that same reason, rovers can share air via hoses you connect between them. That little feature will let me share atmosphere with the trailer on my long drive.

I’d stolen the trailer’s battery long ago; it had no ability to move under its own power. So I hitched it up to my awesomely modified rover and towed it into place near Pathfinder.

Venkat told me to “draw” the shape I plan to cut, but he neglected to mention how. It’s not like I have a Sharpie that can work out on the surface. So I vandalized Martinez’s bed.

The cots are basically hammocks. Lightweight string woven loosely into something that’s comfortable to sleep on. Every gram counts when making stuff to send to Mars.

I unraveled Martinez’s bed and took the string outside, then taped it to the trailer hull along the path I planned to cut. Yes, of course duct tape works in a near-vacuum. Duct tape works anywhere. Duct tape is magic and should be worshiped.

I can see what NASA has in mind. The rear of the trailer has an airlock that we’re not going to mess with. The cut is just ahead of it and will leave plenty of space for the Big Three to stand.

I have no idea how NASA plans to power the Big Three for twenty-four and a half hours a day and still have energy left to drive. I bet they don’t know, either. But they’re smart; they’ll work something out.

[11:49] JPL: What we can see of your planned cut looks good. We’re assuming the other side is identical. You’re cleared to start drilling.

[12:07] Watney: That’s what she said.

[12:25] JPL: Seriously, Mark? Seriously?

First, I depressurized the trailer. Call me crazy, but I didn’t want the drill explosively launched at my face.

Then I had to pick somewhere to start. I thought it’d be easiest to start on the side. I was wrong.

The roof would have been better. The side was a hassle because I had to hold the drill parallel to the ground. This isn’t your dad’s Black & Decker we’re talking about. It’s a meter long and only safe to hold by the handles.

Getting it to bite was nasty. I pressed it against the hull and turned it on, but it wandered all over the place. So I got my trusty hammer and screwdriver. With a few taps, I made a small chip in the carbon composite.

That gave the bit a place to seat, so I could keep drilling in one place. As NASA predicted, it took about two and a half minutes to get all the way through.

I followed the same procedure for the second hole and it went much smoother. After the third hole, the drill’s overheat light came on.

The poor drill wasn’t designed to operate constantly for so long. Fortunately, it sensed the overheat and warned me. So I leaned it against the workbench for a few minutes, and it cooled down. One thing you can say about Mars: It’s really cold. The thin atmosphere doesn’t conduct heat very well, but it cools everything, eventually.

I had already removed the drill’s cowling (the power cord needed a way in). A pleasant side effect is the drill cools even faster. Though I’ll have to clean it thoroughly every few hours as dust accumulates.

By 17:00, when the sun began to set, I had drilled seventy-five holes. A good start, but there’s still tons to do. Eventually (probably tomorrow) I’ll have to start drilling holes that I can’t reach from the ground. For that I’ll need something to stand on.

I can’t use my “workbench.” It’s got Pathfinder on it, and the last thing I’m going to do is mess with that. But I’ve got three more MAV landing struts. I’m sure I can make a ramp or something.

Anyway, that’s all stuff for tomorrow. Tonight is about eating a full ration for dinner.

Awww yeah. That’s right. I’m either getting rescued on Sol 549 or I’m dying. That means I have thirty-five sols of extra food. I can indulge once in a while.

LOG ENTRY: SOL 194

I average a hole every 3.5 minutes. That includes the occasional breather to let the drill cool off.

I learned this by spending all damn day drilling. After eight hours of dull, physically intense work, I had 137 holes to show for it.

It turned out to be easy to deal with places I couldn’t reach. I didn’t need to modify a landing strut after all. I just had to get something to stand on. I used a geological sample container (also known as “a box”).

Before I was in contact with NASA, I would have worked more than eight hours. I can stay out for ten before even dipping into “emergency” air. But NASA’s got a lot of nervous Nellies who don’t want me out longer than spec.

With today’s work, I’m about one-fourth of the way through the whole cut. At least, one-fourth of the way through the drilling. Then I’ll have 759 little chunks to chisel out. And I’m not sure how well carbon composite is going to take to that. But NASA’ll do it a thousand times back on Earth and tell me the best way to get it done.

Anyway, at this rate, it’ll take four more sols of (boring-ass) work to finish the drilling.

I’ve actually exhausted Lewis’s supply of shitty seventies TV. And I’ve read all of Johanssen’s mystery books.

I’ve already rifled through other crewmates’ stuff to find entertainment. But all of Vogel’s stuff is in German, Beck brought nothing but medical journals, and Martinez didn’t bring anything.

I got really bored, so I decided to pick a theme song!