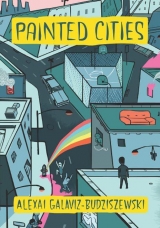

Текст книги "Painted Cities"

Автор книги: Alexai Galaviz-Budziszewski

Жанр:

Современная проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 2 (всего у книги 11 страниц)

PAINTED CITIES

HANGING GARDENS

Rom has his colors down like no one else in the hood. Turned the west face of Speedy’s corner store into a three-dimensional dreamscape, complete with galaxies, shooting stars, and black holes that appear to bore right through the brick wall they’re sprayed on. How he gets his colors to catch light like that, especially at night, when the orange of the streetlamps reflects off his murals in iridescent gleams, is a mystery to everyone. Awestruck, they watch him perform, red bandanna maroon with sweat, clothes and skin speckled with over-spray: baby blue, crimson red, hi-glo yellow.

Speedy had seen the job Rom did on the alley wall of Saint Stephen’s rectory. The Christ on the cross mural: overpowering not because of the crown of thorns, the blood-dripping wounds, or the long, pouting stare Catholics are accustomed to, but because of the way Christ looms above, as if frescoed on the concave surface of a spoon. Around Christ galaxies spin, shooting stars streak, and his white gown flows in a cosmic wind. To this day the mural is a routine stop on the North Side’s bus tours into the heart of the city.

Most of Rom’s pieces are commissioned by area businesses or churches – maybe even the public, if Rom takes to heart the suggestions he hears while working. “Hey, bro, how about dedicating to my girlfriend, Flaca?” “How about to my mother?” “My grandmother who died yesterday?” But his dedication to Arelia Rosas, a ten-year-old girl who disappeared the summer before last, simply appeared one morning without warning on the octagonal brick kiosk that sits before the old Lutheran church on Nineteenth and Peoria.

The neighbors called the mural “poignant,” though many were unsure of what the word meant. It wasn’t negative, though, most were sure of that, so they used the word over and over to describe the dedication until months later, when the word dropped from favor through sheer overuse.

In the mural, a caricature of Arelia sits alone on the wood bench her grandfather made for her many years before and placed in front of the ground-floor apartment he lived in. How Rom knew this intimate detail of the Rosas family, no one knows, but they chalk it up to an artist’s intuition. Anyone passing the scene sees the bench, the brick-molded asphalt siding of her grandfather’s building, and knows immediately the moment takes place in summer, that there is an open fire hydrant somewhere nearby and that the scents of the neighborhood – frying tacos, boiling pots of garlic-spiced frijoles, cool Lake Michigan breezes transported by miles of sewer pipe – layer the atmosphere.

She sits playing with her hair. Everyone remarks how Arelia could just sit for hours, contented, smiling to herself occasionally when something funny came to mind. “But she never cried,” her mother says. “No, never.” Yet in the dedication, as contented as Arelia seems, chrome tears run down her high cheeks. This is where poignancy takes place.

Within the basket of each tear a city appears, like a hanging garden. Upon close inspection the image is revealed as a portrait of the neighborhood itself, shot from above, minute down to steeples and the path of the L as it snakes down Twenty-First Street. How he got his spray down to such fine points no one will ever know, and this is an issue of contention among the local graffiti artists: whether or not Rom actually broke the rules and employed brush. But the haze is there, the over-spray, the telltale sign of aerosol art, which, in this case, enhances the already translucent tears, the cities held within glass bulbs like holiday paperweights filled with liquid, begging to be flipped and allowed to snow.

The tears don’t stop at the cheeks. They continue to fall: two are in midair. Eventually, one glances off Arelia’s white knee and multiplies in a flash, producing more tears, finer tears, smaller cities. The silver droplets reach the image’s painted cement sidewalk and sink into what now appears to be a vast city in and of itself, splayed out beneath the reflective sheen of Arelia’s black patent-leather shoes. Corridors of streetlights, side streets, meet at infinite points around the kiosk. At times, the neighbors say, the painted cities come alive, movement can be seen, the L’s slithering like hobby railroads. The neighborhood’s lowriders stop and go on the boulevards.

Rom takes no credit for his murals. Never signs them, unless somewhere in the jumble of letters at the bottom of his pieces the name ROM is encoded. The neighbors call this humility, though many are unsure of what the word means. They use it anyway, while they wait for miracles.

RESIDUE

Could’ve been Death himself, the grim reaper, descending into the basketball court that night. Could’ve been ready to pull out any number of weapons, automatics, pumps, side-by-sides – everyone knows the grim reaper don’t use sickles no more.

Grim reaper lookedlike he grew up South Side, way he pimped down the alley ramp into Barrett Park. Even though ol’ boy was walking slow, that slight bump in his step was all South Side, Twenty-Second and Damen to be exact. Could name the street corner by that walk alone.

First thought was he’d been living in somebody’s basement. Jose Morales, valedictorian at Juarez High School, thought it, and Sleepy too, twelve-year-old, droopy eyed Party Boy in training. Everyone in the park that night thought it. That, and how the world got awful small sometimes. Like just last week, when Beany from the Two-Ones found out his old lady was fucking some dude where she worked downtown. Xerox repairman wound up being Juice from the Party People over on Allport, Beany’s best friend when they came up together on Eighteenth. Two days later Juice was found tied to an alley lamppost, alive but beaten. Beany’s out hunting for his old lady now; he’s got something more serious in mind for her.

Jr. Chine stood at the far end of the basketball court watching the scene develop. He wasn’t afraid of anything he could see, at least that’s what he liked to tell himself. He’d heard Juice’s story, how Beany was now after his girlfriend. “Motherfuckers should’ve seen it coming,” he’d told Joker, his Party Boy brother, his best friend in the neighborhood. “You look for trouble, shit’s going to find you first.” Joker’s only response had been to laugh. Joker was a thief, of everything.

But it figured the grim reaper was living in the neighborhood. Probably renting out a musty concrete basement for a buck fifty a month, utilities included, stolen from a next-door neighbor. Might have assumed the name Julio Ramirez, or Juan Calderon, one of those generic Mexican names nobody’d suspect it was Death himself, coming in at strange hours. Whoever owned the building, the landlord living in the front, highest apartment, like they always do, probably thought Death was just a good worker. Probably thought he was some mojadobusting his ass making calculators in Elgin for fourteen hours a day, wiring cash back home to Mexico, supporting seven growing children and a wife named Iris, or Esmeralda, some name that brought to mind young beauty, though she herself was tired and worn. Landlord probably thought to hire Death too, being he was such a good worker. Give him twenty bucks to patch the front sidewalk, holes so big kids be falling down there, assumed kidnapped until someone heard the screaming.

And all along it was the grim reaper, filling in holes, living in the neighborhood, existing incognito.

Jr. Chine said it first, to no one in particular: “Hey, bro, that’s Joker.” Exactly how he knew the grim reaper was really Joker was impossible to tell, but they were good friends, and good friends can generally sense one another, like when you know a hit’s pulling down the street five minutes before you actually see the car, cab darker than the street itself, orange street light thick as humidity.

It had been Jr. Chine’s shot. He’d had the ball on the low post, about to release his patented baseline jumper, dramatic for its disregard of the backboard, its confidence as it cycled through the air and then swooped the chain-mesh net. The ball dropped from his hands like a whistle’d been blown. It trotted toward the field house, down the slope of the compressed basketball court, each bounce accompanied by the twang of an overinflated ball, into the slot between the cyclone retaining fence and the back of the brick building, where ball players, drunks, and wicky-stick fiends pissed, the piss collecting over generations, reeking, giving the field house its neighborhood moniker, “Stinky.”

The figure’s hands were hidden in his sweatshirt pockets. The deep hood hung low over his brow and his arms were locked at the elbows. The material was being stretched down as if the figure were cupping his balls, making the body seem even more ominous, an open mouth screaming, melting. If the crowd on the court could’ve seen the hands, a positive identification could’ve been made. They would’ve known for sure it was Death: long, white fingers, black fingernails. Or they would’ve known it was really Joker: bleeding crucifix tattoo on the web of his right hand, PARTY BOYS etched in Old English script like a banner over the crucifix. Jr. Chine approached the descending figure cautiously, his own right hand gripping the.25 automatic stuffed in the pocket of his cutoff jeans. He flipped the safety off, though, like always, he questioned immediately whether he’d actually flipped it on, and was now about to die feeling stupid. If he lived, he vowed, he’d memorize which action was the correct one, get the safety situation down pat, like he had the clip-loading maneuvers down pat, practicing for hours as he lay in bed, popping the clip in and out, in the dark, sightless, the clicks of the release mechanism like second nature. He sidestepped toward the figure. His steps shortened as he neared. And suddenly Jr. Chine’s vision went third-person. Everything – the game, those standing behind, the cigarette Jr. Chine had left smoldering until he was back downcourt – disappeared from view, and he could see it all as if he was living his own movie.

“Joker, what the fuck are you doing?” Jr. Chine said. And a tiny voice came from the hooded figure.

“Hey, bro, we need to find Angel.”

“Who the fuck are you?” Jr. Chine said, now loud and boisterous, his adrenaline sky-high. He bobbed and weaved as he moved around the figure. “Take off that hood so I can hear you.” Jr. Chine’s hands were wet. His right hand around the grip of the gun had become cold, though the rubber grip itself remained hot. He pulled the gun from his pocket and held it stiff-armed at his leg.

“It’s me, bro,” the voice said a little louder, the hooded head following Jr. Chine as he juked and stuck.

“Joker?” Jr. Chine asked.

“Yeah.”

Jr. Chine cocked his body, ready to spring into action, then reached out and peeked under the hood. It wasJoker, though with all the welts, the fluvial bruises around his eyes, the fresh slices to his cheeks, it was hard to tell. Jr. Chine’s trigger arm went limp, his elbow finally unlocked after what had felt like hours. Vision reeled itself back in. The burning in his arm remained, but he relaxed and put the small gun back in his pocket.

“Hey, bro,” Joker said. “Angel’s on his way to kill Susan.”

“Susan who?” Jr. Chine said.

“His lady, bro.”

UNDERGROUND

There are cities down there, Little Egypt said so. He said they’re smaller cities, not nearly as many people, but they have traffic and L’s, just like we do up here.

The subway used to connect. Little Egypt said that too. That the Douglas-Park B Line used to take a steep dive right after LaSalle Street and descend into the cities below, neighborhoods stacked on top of one another deep into the earth, like department-store floors. “But then,” he said, “they built downtown, John Hancock and all that. Now the subway just flies right over, Jackson Boulevard, Monroe. People up here don’t even care anymore.”

I saw Little Egypt’s suitcase once. He kept it stored beneath his bed, packed and ready to go if he ever got the call to leave. “My grandfather took this baby all around the world,” Little Egypt said; he hoisted the suitcase onto his bed. “Should handle a trip below, I’d think.” He patted the swollen hide, then curled out his bottom lip and nodded.

Inside were a lot of shorts. On the underside of the top flap a ziplock bag had been taped. A thick purple cross had been drawn on it, and beneath the cross, FIRST AID was written in large block letters. He untaped the bag and split the seal. Band-Aids, gauze, a spray-can of Bactine, a pamphlet on snake bites poured out over his blue comforter. A few sets of chopsticks from Jade of the East Chinese spilled out as well. I lifted a set. Along the paper wrapper JADE OF THE EAST was written in familiar Oriental script. A local address followed, then a picture of a Chinese temple, layered, like a playing-card house.

“That’s my grandmother’s favorite restaurant,” Little Egypt said. He took the set of chopsticks from me and tore off the temple end. He split the sticks. “They make great splints.” He placed one along his thin forearm. “And communication tools.” He tapped out Morse code: “SOS,” he whispered. “And great weapons too.” He did a pirouette, then waved the chopsticks in my face. “Hi-ya,” he snarled. “But they don’t really fight down there.” He straightened and put the chopsticks back in their paper sleeve. “Really, it’s a more peaceful society.”

Double-D batteries were taped like shotgun shells along the inside wall of the suitcase. From between his piles of T-shirts and shorts he pulled a red plastic flashlight. He offered it to me and I flicked it on, casting a sharp yellow beam against his white wall. “I’ve had that puppy for years,” Egypt said. “Never failed me. Not once.” He curled out his lower lip again and shook his head. “Never.” I flicked off the lamp and handed it back to him, grip first, the way one does a pistol or switchblade. “I mean, they have lights down there and everything,” Little Egypt said. He tucked his flashlight back in between his clothes. “But it’s better to be safe than sorry.” He pulled a roll of clear packing tape from a bureau drawer and retaped the first-aid kit to its position on the underside of the top flap.

Sometime later, one morning before school, Little Egypt was at my door, suitcase at his side. He was dressed in his church clothes: a red knit sweater, tan slacks, brown loafers so polished they seemed wet. It was early spring, the sun was unusually high and bright.

“Just wanted to say bye,” Egypt said. He smiled, his row of tiny teeth nearly fluorescent. I offered to walk him, and I quickly dressed and washed my face. Over the running water of our kitchen sink, I heard Egypt on our front stoop, whistling.

We walked down May Street.

“I left a note for my grandmother,” Little Egypt said. “She should see it when she gets back from church. I’ll write her, of course. I just didn’t want to be too specific, tell her exactly where I’m going. Sometimes,” Little Egypt said, “a man just has to break free.” I nodded.

We passed the graffiti-covered field house of Dvorak Park, the pool, shards of broken glass catching sunlight along the concrete deck.

“That’s one thing I won’t miss,” Little Egypt said, looking to the pool. “The pollution. They got a system down there, you know. Cleans all the streets. They never even heardof graffiti.” He gave a nod as if there were a valuable lesson in this. Our field house’s shower-room walls held messages: Ambrose Love. Flaca, You Know I Still Love You, Junebug.

At Twenty-First Street we turned the corner and walked toward the abandoned junkyard. “Well,” Egypt sighed. He put his suitcase down. “I guess this is it.” He stuck out his hand. “I’ll be sure to write, and I hope to see you again sometime.” He clicked his tongue twice and winked. Then he lifted his suitcase, turned, and walked down the quiet street. As he walked, the heavy suitcase bounded off his short leg; he held out his opposite arm like a cantilever. I realized then how small he was.

He stopped halfway down the block in front of the junkyard office. He stepped off the curb to a familiar sewer grate, one I myself had looked into often as I combed our neighborhood for loose change. The smell of wet metal spilled over the junkyard’s corrugated walls – rust, oil. In the distance an L rumbled across Eighteenth Street, traffic whined on the Dan Ryan, a truck ground through its gears on Twenty-Second. I heard everything in echo, my ear to the city, one giant seashell.

“Hello!” Egypt called down into the grate. He was in a squat, his suitcase alongside him. He looked to me and smiled, then waved. The brown of his church shoes stood out red in the morning sun.

“Hello,” he called again. “Anyone down there?” At that moment I realized I was about to lose my only friend.

THE CITY THAT WORKS

Puppet plays guitar. He strums his strings on Eighteenth Street and Wolcott, in the narrow gangway between Zefran Funeral Home and the El Milagro tortilla factory. There at night, the notes bounce up the brick walls around him and create an echo that Puppet believes he’ll one day record and sell for millions of dollars.

He plays old tunes: Ritchie Valens ballads, Santo & Johnny’s “Sleep Walk.” He thinks he’s romantic. When the L’s rumble by, he continues playing, convinced somehow that his music is affecting the travelers: making a pickpocket reconsider as he slips his trigger hand toward a sleeping passenger’s pocket.

Puppet can play the first few bars of Ritchie Valens’s “Donna” like an expert. The rest he fumbles through, and he returns to the chorus like it’s his lifeboat. The hair on the back of his neck stands on end. He wonders if those on the outside, those at either end of the dark gangway, where the orange of the streetlights glows in long, vertical slits, are feeling it too. Often, when he steps out of the gangway, he expects entranced crowds to be gathered there: beautiful women with tears in their eyes and a love for him undying. Of course, there never are – just the hum of the city at night, things on autopilot, neon signs, streetlights, the clicking of stoplights. Overhead another L rumbles by like a strip of film, only one or two of the yellow frames actually holding a silhouette.

Across the alley, in a bedroom on the top floor of a three-flat, a young girl sighs. She turns from her open window and faces the darkness. She hugs her pillow. “I love you, Ritchie Valens,” she says. “I love you.”

FREEDOM

Iknew Buff before he was a Latin Count, before he was shot dead. His real name was David. I heard his aunt call him that once, when we were on top of the old pierogi factory. “David!” she called out. And Buff looked at me. “Shit,” he said. He dropped the rock he had in his hand and went running across the gravel roof. He climbed over the air-conditioning unit and disappeared. I was up there alone then. I looked over the ledge onto Twenty-Second Street, the traffic. I looked at the kids playing swifties in the school playground across the street. I dropped my rock and climbed down as well. Throwing rocks wasn’t fun unless you did it with someone.

David, or Buff, thought different. I had first met him a few months before, when my father had sent me to the A&P to get some milk. I was approaching the pierogi factory, just across Oakley Avenue. It was hot out that day; the sun felt somehow closer. WHACK!I heard. Across the street, a CTA bus screeched to a stop. The driver turned and stared back at me. Behind him, one of the large safety-glass windows had been shattered – a cool, spiderweb-like pattern spread over the entire pane. I looked to the sidewalk and continued walking. Finally, the bus moved on.

After it had crossed Western Avenue I turned and looked behind me. There, on the pierogi factory roof, standing at the ledge, was a boy my age, maybe a little younger, wearing a white T-shirt. His head was shaved. He had big ears and a smile that made him look something like Dopey from Snow White. He nodded at me as if he knew who I was.

“How’d you get up there?” I asked him.

“Around the back,” he said. His speech was quick, almost hyper. At the end of his sentence he sucked his tongue, like he was fighting back saliva. Then he disappeared beyond the ledge.

I continued on to the A&P. I kept looking back. I imagined couches up there, tables, a secret hideaway. I was jealous. The pierogi factory roof was one of the last frontiers of my neighborhood. It was only two cinder-block stories high, but its remoteness, its sheer walls, made hiding up there seem equal to never having been born.

The second time we met we became friends. I had figured out how to get up onto the roof myself. The key was the chain-link fence that enclosed the factory’s dumpster – at one corner the fence could be scaled, and then it was a matter of balance, a tightroper’s balance, skirting lines of barbed wire to the factory’s air ducts. After a leap to the thin sheet metal of the ducts, it was like climbing playground slides in reverse. Once, twice, three times, and suddenly you were there. It was amazing how easy it was. The pierogi factory roof had always seemed so impenetrable. I’d scaled garages. I’d scaled abandoned warehouse fire escapes. I’d even scaled the Western Avenue L stop, using the steel straps that held the support beams together as footholds. But I’d only ever dreamed about gaining the roof of the pierogi factory. That first time up there I surveyed the terrain: blank, empty, a white-gravel roof with a huge, green-painted air-conditioning unit. I was disappointed. Still, no one else I knew had ever been up there. Except, of course, for Buff, whose name I didn’t even know yet.

It was a beautiful view, Twenty-Second Street, the street I lived on. I’d walked Twenty-Second so many times I knew every crack and buckle of its dilapidated sidewalks. But seeing it from two stories up, seeing each expanse of concrete imperfection, was awesome. The sidewalks seemed to make sense from up there; one could almost read the streets, the way they dipped and turned, how the sidewalk simply followed suit. I took a seat on the ledge of the roof and picked up a rock. I dropped it down to the sidewalk, waited for the sharp snap.

Across the street a large group of gangbangers, Disciples, were playing basketball. Their voices echoed loud and clear off the school building behind. “Ball! Ball!” they called out. “Foul, motherfucker! Goddamn!” It occurred to me that from up there I could be a spy if I wanted to. I could climb the roof late at night when the Disciples were having their meetings and overhear plans for drive-bys, cocaine sales, turf wars. It occurred to me that I could go to the Laflin Lovers or the Bishops, archrivals of the Disciples, and sell their secrets. I was hatching plans, schemes, when suddenly, behind me, the gravel churned.

He was there, standing. He was short, much shorter than he looked from two stories down. He was younger-looking as well.

“Ha!” he said. “I knew it, bro! I knew you’d find the way up here.” He sucked spit. “You climbed the fence, didn’t you?”

“Yes,” I said.

“Ha, I knew it!” he said. “No one else knows how to get up here. Just you and me.”

I thought about this. In the end the climb hadn’t seemed that difficult.

“Yeah,” he said. “No one knows…”

He sat down next to me. He scooped up a handful of rocks. He had blue eyes. This was strange. He was Mexican, just like me; he had dark skin, dirty summerskin, but he also had these almost pastel-blue eyes. His face was lit up. He was smiling.

He shook his handful of rocks, loosing a couple. He looked down to the street. The noise of the basketball players came to us. “Center. Ball!” His eyes moved to the kids on the court.

“That’s my cousin over there,” he said. “Right there, see, the one with the ball.” He looked down to his handful of rocks, shook another couple free. “His name is Junebug. He’s a D. He’s a little crazy.”

I studied the kid with the ball. I’d seen him before. He looked like the type that liked to corner younger kids against the walls and ask them, “ What you be about?” I avoided kids like him, crossed the street when I saw them coming.

“He shot me with a BB gun,” Buff said. “Like three days ago.” He pulled up his T-shirt and showed me. On his belly were three small welts, each holding a tiny, deep, dark pit in its center.

“He shot you?” I said.

“Yeah,” Buff said. He laughed. He let his shirt down. “Ha ha, it didn’t even hurt!” He looked down to his handful of rocks, shook out another two.

“You should go to the doctor,” I told him.

“I should, right?” he said. “Aaaa.”

Buff looked out over the ledge. By this time there was only one rock left from his handful. He looked far down the street.

“All right, bro, here it comes,” he said. And then, in a split second, Buff jumped to his feet, fired his rock over the ledge, and ducked back down. I followed him, ducking too. I heard a loud POP, then a long screech of tires.

“Damn, bro, that was a cop car!” Buff said. “I got them, bro! I got the Law!”

I stayed low. I didn’t want to see.

After a few moments I couldn’t help it. If it wasthe cops, I thought it might be better if I turned myself in. I peeked over. Down on the street, a fat man wearing a red baseball cap was inspecting the shattered windshield of a rusted green station wagon. The man was dirty, sweaty, like he’d been working all day. His car didn’t appear to have any backseats, only chunks of concrete filling the space from the driver’s seat all the way to the tailgate. Stuck out of the back window was a bent metal pole with a red bandanna tied to its end. Two other people were down there, a couple. “ Pinche cabrones,” the man said. He shook his head and took his cap off. “ Pendejos,” he said. He rested his forearms on the roof of his car and then brought his head down. The couple walked away.

I tucked back down behind the ledge.

“It wasthe cops, wasn’tit, bro?” Buff asked.

“Yes,” I told him. “I think it was the narcs or something.” I swallowed hard.

“I knew it, bro,” Buff said. “I knew it was the cops. My name is Buff,” he said. He sucked spit.

“Jesse,” I told him. I shook his hand.

That summer we were inseparable. I found out Buff was ten, the same age as me, although he looked like he could be a year younger, maybe even two. I found out that he lived on the North Side, but that he was spending the summer with his aunt on Twenty-Fourth Place because “people” were after him. I asked who the “people” were but he didn’t want to tell me. He said: “Maybe you know them. I don’t want to start any shit.”

I also found out that Buff was going to be a father. That he had a girlfriend named Letty who occasionally visited him. She was seven months’ pregnant, Buff said.

“Isn’t your family mad?” I asked him.

“Yeah, but what are they going to do?” Buff said. “Besides, we’re in love.” I nodded like I knew love could be the reason for anything.

One afternoon we were up on the roof drinking some Cokes I had bought from Midwest corner store. I was staring up into the sky, listening to the traffic. Buff was looking over the ledge. We were talking about cars, maybe, or what prison was like. And then Buff said: “Look, there she is. There she is, bro. That’s Letty.” I turned and looked over the ledge. Across the street a group of girls were talking to some of the basketball players. “The one with the white shirt,” Buff said. I looked to her. She was pretty. In fact, to me, at my age then, she was beautiful. She was thin, tall. She had short, dark hair. She looked like an older girl, like she was in high school. She smiled a lot, seemed genuinely happy about things. When she talked she moved her hands. When the boys spoke to her, she rolled her eyes. She did not look pregnant.

“That’s Letty?” I asked Buff.

“Yeah, bro,” he said. “I forgot to tell you she was coming down here today.”

“She’s talking to all those D’s,” I told him.

“I know,” he said. “That’s her cousins. Most of those guys down there.”

I watched the girl move. I watched her pull back her hair as if she could put it in a ponytail. I heard her laugh out loud once. It was a deep laugh, like she had never been unhappy.

Finally, she and her friends walked away. When they were in the middle of the block Buff yelled out, “ Let-ty!” He tucked down behind the ledge. “I don’t want her to see me, bro,” he whispered. “She doesn’t like it when I call out her name like that.” I lowered my head but continued to watch. The girl turned and looked behind her. In the playground the boys were already back to their game. She looked in front of her, across the street. She looked to her friends. They all laughed together.

“Did she look?” Buff asked.

“Yes,” I told him.

“Damn, she knew it was me,” he said. “She’s going to be pissed later.” He shook his head.

I rested my chin on the ledge and watched as the group of girls walked away. Buff came up and watched as well.

“Those girls are bitches,” he said. “They talk too much.”

This is how we spent our time. Sometimes throwing rocks, but mostly just talking. Buff showing me things, telling me what it was like to sniff cocaine. In truth, I don’t think I believed much of what Buff said. I simply went along with it.

One afternoon he asked me if I’d ever smoked angel dust. “Yes,” I said. “It’s crazy, right?” Buff asked. “Yes,” I answered.

I often wonder if Buff knew I was lying. But up on the roof, between the two of us, it didn’t seem to matter. Sometimes I even question whether I actually spent a summer on that gravel roof, but then I think about what happened, and I know that I did.

The idea came to us at night. Back then my rule for coming home was the streetlights. When the streetlights came on I was to start heading home, no matter where I was. I followed the same rule when I was up on the roof, but I dawdled. I was only a block away from home. When I arrived and my father asked where I had been, I told him that I had been at Harrison Park, or some other place that took equally long to return from.