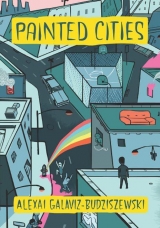

Текст книги "Painted Cities"

Автор книги: Alexai Galaviz-Budziszewski

Жанр:

Современная проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 10 (всего у книги 11 страниц)

SUPERNATURAL

Only a miracle could draw people to that canal. It has been forgotten about, shut off from the main river years ago, left as a depository of dumped appliances, cars, street-gang hits.

It’s the perfect ghetto miracle. The toxic haze glowing bright green as if its light were filtered through emeralds. Maybe the years of dumped chemical solvents from the factory alongside it have finally yielded the kind of catastrophe scientific experts have anticipated for years. But this catastrophe is beautiful. A fluorescent haze that comes into sight each night, deepening as the heat of the day settles around the neighborhood.

They’ve been coming here for a week, the crowds, getting larger each successive night. The canal banks can barely hold the masses of people now. The spectators have begun spilling over into the factory’s gravel parking lot, onto the bridge that spans the canal, onto Thirty-First Street, filling it in for blocks, as if in exodus.

Word has obviously gotten around. Probably passed along the front stoops of the neighborhood like hot merchandise. Down Twenty-Sixth Street, past the Cook County lockup, past the taco stands, the corner taverns, the story indulged a little more with every pass and reception: The glow’s deep, man, I mean deep. People are being cured and shit. Lil’ Ralphy can walk again.

The words would have sailed over the junkyards, the sleeping drunks, the trade school, the abandoned drive-in. They would’ve come to rest at Cicero Avenue, where the ghetto stops and a vast field of open prairie spans from there to the next neighborhood. The words would’ve mixed in with other marooned statements, the old news that had come to rest there, no one left to listen: Crazy Frankie shot Player. Got me some wicked shit. The bitch is dead.

Memo, everyone agrees, should’ve been the first to appear, charging money for canal-side seats, a dollar a pop, like he charges for his snow-cone raspas, his cucumber pepinos, every time there’s a police investigation. With his nose for disaster, kids spend their summer days following him around the neighborhood, cheering when he starts his sprints, which sometimes last for blocks, ending at the next brutal event. His swift parades flash between buildings. His handcart bells jingle. His red baseball cap beckons the kids to follow. Eventually they stop at some place where there’s blood in the street and Memo starts to call out, “ Raspas! Pepinos!” not even winded. The kids, panting, lean up against each other and savor the carnage. Sometimes, if they have money, they pitch in and actually buy something.

But Memo, even with his nose attuned as it is to moneymaking opportunities, couldn’t detect the event, didn’t. And the brujas didn’t either, the back-alley witches of K-Town, where all the witches are said to live, drawing power from the uniformity of the street names – Karlov, Kedvale, Keeler. And maybe, at the heart of it, this is the appeal of the green glow. How those normally attuned to the supernatural, those who seem to have a “sixth sense,” seem dumb-struck, as if it were beyond their comprehension.

The event has taken on an air of revival. Estranged family members are reunited, quarreling relatives embrace, old partners, gangbangers, are brought back together as if their differences, their knife fights, their nights spent hunting for each other with baseball bats, had never occurred. “Just like old times,” they say to each other. And this phrase permeates the crowd. Husbands are reunited with the mothers of their children. Boyfriends hug ex-common-law wives. The night becomes one big flashback. Everyone sliding one step back to a time when they were happy, or at least thought so.

Around nine o’clock, when the buzz of the insects turns to a strong throb, and the sun, somewhere behind all the haze, the buildings and church steeples, starts to set, the crowd quiets, and a flicker of green starts to snap at the center of the canal, just above the water. The flicker jerks and twists, then explodes into an opaque globe of light, strong, like a spirit, like you expect it to talk – but it doesn’t. It just hovers there, casting a white light that passes into green as it reaches the crowd. The pulse of the insects fades, conversations, thoughts, movements stop, and a dullness takes over.

A freeze-frame, a wide-angled freeze-frame showing the long expanse of Thirty-First Street, its corridor of streetlights stretching into the horizon, would show the crowds en route. It would show them all staring up, pointing as if at fireworks, a glaze across their eyes as if they were under mass hypnosis. Some would be caught with their mouths open, black gapes, white teeth catching the light, streetlight maybe, but maybe the light of the glow as well.

Young women would be caught looking innocent. Those with tattooed tears, those holding babies, would be caught looking like their children, sharing their defenselessness, their vulnerability. And the young men too would be caught smiling the way gangsters do when some truth is revealed – innocently, giving one the slightest hope that they could be reasoned with, “saved,” as some of their mothers might say. Of course, they never can be. Gangster faces change like masks. They’re defense mechanisms. But in the freeze-frame the gangsters would be caught red-handed, smiling like bashful teenagers, as if they’ve suddenly found the right answer to a math problem on the blackboard before a class of schoolmates raised from the dead.

In the freeze-frame, Thirty-First Street would be crowded, ready to burst its sides and collapse the walls of the abandoned buildings that line its sidewalks. The exodus might be confused with any other pilgrimage, quests to view saints, kiss the feet of monks, to discover the meaning of life in deserts in Saudi Arabia, atop mountains in South America.

At the bottom of the freeze-frame, those closest to the glow have begun to take seats, resigned to the thought that they won’t get any closer, overwhelmed by whatever the green glow holds.

And this goes on all night, through the heat. The drunks stay awake. The clergy from the local churches lead prayer sessions. Memo, the vendedor, stands there, his band of children crowded around him. The witches’ assistants scan the crowd for more faces, those of the dead, the forgotten, more of whom seem to appear each night.

As morning comes, the very first tinges of light sliding up the horizon, the green glow begins to fade, and so does the mystery of whatever brought the people here. Shadows give way to starkness, reality, and slowly the people begin to move, some slower than others, embarrassed by their own gullibility. As they make their way back up Thirty-First Street to their sweatbox apartments, they crowd in closer, like cattle, seeking safety in numbers. They avoid eye contact, slouch as if hung over. They carry their sleeping children, the mothers following the fathers, everything in reverse. There is an aura of defeat to the crowd. Truth becomes apparent. There is only heat to look forward to, days spent at work, in factories, as secretaries, days spent in bed, days spent watching Memo charge up and down side streets, days spent believing in God, witches, prayer, the coming of another night.

ICE CASTLES

On the south side of Chicago, at Harlem Avenue and Archer, Joe and Frank’s Meat Market pumps out smoked kielbasas like clockwork. Every Wednesday and Friday the smell of burning hickory fills the intersection. If the air is stagnant, smoke billows from Joe and Frank’s chimney and fills the street corner like fog. But when the wind is up, the smoke carries. I live in Berwyn, a full three miles north of Joe and Frank’s, and still, on a good day, with a gust of wind from the Bedford Park Intermodal, a blast of air from the Sanitary and Ship Canal, I can pick up the scent of Joe and Frank’s. It reminds me of my childhood and of Pilsen.

Pilsen was marooned by relics, locked in by ancient industry. To the north was the old C, B & Q Railroad yard, rusted arrays of tracks twenty or thirty sets wide. To the east was the Chicago River and its permanently raised bridges. And to the south was Twenty-Second Street and its mile-long stretch of power plants, vacant warehouses, and junkyards. Pilsen was tall, dense, massive. The only reprieve was the uniformity: the open-air gangways that matched up perfectly from block to block, the side streets that ran uninterrupted through Pilsen. At any point in the neighborhood, down these corridors, our borders were in full view: the abandoned bridges at the river, the terrifyingly dark viaducts at Seventeenth Street, and above it all the fuming smokestacks of Twenty-Second Street.

Our houses were our reflections, cramped, utilitarian. We lived atop one another in wood-frame, two– and three-flat apartment buildings, clapboard siding like stereo-sundials as the sun rose and set. All of our houses were off-kilter somehow, a limping back porch, front steps crumbling and broken like ancient ruins. In some cases the flaws were inside, like in our apartment, where I could roll a penny in the kitchen and have it continue through the living room, pick up speed in the bedroom, and, if the back door was open, hop the threshold right out onto the porch. Pilsen had its share of stone-faced buildings, storefronts, brick churches, corner tenements, but these were torn up as well, mortar dark and broken like rotting teeth, soot rising in columns from wall-mounted chimneys. Pilsen was dark, forever. We lived in shadows with railroad tracks beneath our feet, tracks that ended at walled-off docks or rusted-over bumpers or sometimes at nothing at all, two lines side by side cut off in the middle of a street, traffic beating the ends into the asphalt, burying them slowly, inch by inch, like the whole city was sinking, Pilsen first.

Back then my father was a cab driver. He was in school studying to be a social worker. I didn’t see him much. My mother was a secretary. She worked at an insurance agency, a social-service agency, the phone company: she changed jobs so often I stopped wondering where she worked. She would sigh as we ate dinner alone in our tiny kitchen. Sometimes I would sigh back. “Bad day?” my mother would ask.

“Yes,” I would answer.

“Me too,” she would say.

There was nothing excessive about my family’s existence. We didn’t go out for breakfast. We didn’t order Chinese food. We ate beans and tortillas, fried potatoes, the occasional egg with my mother’s green salsa. My mother made one thing each Sunday without fail, a pot of frijoles, and in the winter the kitchen window would fog over with steam and the house would smell of garlic and onions. In the summer when all the windows of the neighborhood were open and all of Pilsen was making its frijolesfor the week, the whole neighborhood smelled of garlic and onions.

Memories of my father during this time are sparse. I used to see him asleep on the couch as I got ready for school. Sometimes I would wake to use the bathroom and he would be at the kitchen table eating leftovers. The streetlight outside would illuminate our white curtain; our white table would reflect the dim light of the kitchen. My father would watch me walk across the kitchen and into the bathroom. Then, when I was done, he’d watch me walk back across the kitchen, everything in total silence, like he was afraid to speak. As it stands, most of our encounters during this period seem more like dreams than actual memories. And really what seems most stark about those memories is the checkered-flag floor in our old kitchen, the tall, rotted step to get up into the bathroom, the painted-over hook on the door, the orange streetlight shining through my mother’s sheer curtain. The image of my father sitting there is so vague I’ve nearly forgotten it: my father is a forgotten dream, how much more detached can I be? But we had the fires, him and me. If not for the fires I might have forgotten who my father was altogether.

I am sure he spotted them while out on his route or maybe on his way home from the garage. What alerted me were his whispers: “Hey, want to go check out a fire?” With that I would sit up, throw on whatever clothes I could find, and off we’d go, down our apartment building’s steps, out the front door, out into Pilsen. That first breath, that first inhale of charred wood, brought me back into the world. It was like morning coffee or that TV ad for hand soap where “ the scent opens your eyes.” With that first breath of burning wood, I could tell where I was again: Pilsen, early morning, with my father. A house was burning.

A big fire added halos around the streetlamps, smoke hanging in the air like the three-flats were skyscrapers. An even bigger fire brought flurries of ash like black snowflakes falling to the sherbet-tinted sidewalk. If the fire was close enough, it looked like a premature sunrise as we walked down May Street. Emergency lights, red, blue, white, filtered down the long, deep gangways like panels on a revolving lamp. We’d turn a corner or two and then we were there, flames roaring from windows, from roofs. Ladders, streams of water, wet pavement like sheets of polished glass cut by the thick, dark, inflated fire hoses.

There were no small fires in Pilsen. Our houses were like matchsticks, flammable and close together. Asphalt roofs, asphalt siding on wood frames, wood-framed porches, wood-beam floors: inevitably, during a fire, flames would jump to one or two neighboring buildings and then, as smoothly as a train leaves a station, the firefighters would pull their hoses across the mouth of the gangway, toss up new ladders, crash in windows, and begin the battle all over again.

Warehouse fires were the largest: three or four engines, water cannons, platforms, snorkels. The approach was different as well, constant streams of water, calm delivery. Floors collapsed, roofs collapsed, walls collapsed, but the firefighters took it all in stride, let it happen, talked, drank coffee, let the blaze wear itself out. In a house fire, a tenement fire, chaos was always about to break free. Windows were punched out, roofs were ripped open, walls were pulled down, all while melting asphalt dripped globs of flame from two– or three-story eaves. In a house fire, ladders got put up against windows and firefighters came down with squirming pets, crying survivors. Sometimes they came down with bodies, limp and unconscious. Sometimes the bodies were quite small. My father and I watched all this from a distance, in the galley of other witnesses, neighbors, aunts, uncles, unprepared fathers, sons, fire chasers, folks on the way home from third-shift jobs they took just to get by, to survive, paying rent on a lopsided, creaking-in-the-wind, tinderbox apartment. We stood shoulder to shoulder, saw each other sometimes twice a week, in the winter when the kerosene heaters started up and the fires got more frequent, but we never spoke, barely exchanged a glance. The galley was anonymous. We were all from Pilsen, that much I knew.

Waking up after a fire was always rough. It was like I needed a breath of charred wood, a first inhale, to ease me back into life. Instead it was the doldrums of a regular day, my father on the couch, puffed-rice cereal, my mother driving me to school. Sometimes we would pass the night’s burned-out remains and for a moment I’d have a flash, a spark of memory that brought me back to reality, though which reality I wasn’t quite sure. I was standing here a few hours ago. I saw this building in flames. The blackened space was sometimes a confirmation, more so if the actual structure was still intact, but the memory never seemed any more real than a dream, any more real than my memories of my father. As we drove past I would intentionally turn away. Back then it seems I lived life night to night rather than day to day.

The blaze I remember most happened during the winter. The building was a four-flat with a stone facade. It had a straight roofline with brackets holding up the ledge, like on an Old West saloon. As far as Pilsen goes, it was one of the more modern buildings. Across the street was Gracie’s, the laundromat my mother used when Mable’s on Eighteenth was crowded. While waiting for clothes, I’d look directly out onto the building, watch families pass, walk into Zemsky’s next door, then walk out and pass the building again. The building was taller than either of its neighbors. It looked squeezed in, muscled in, like it was taller only because of the pressure to either side. When you took in the panoramic view, the building’s situation seemed even more unfair. Blue Island Avenue was an angled street. The blocks were extra long, extra crowded. This was the only stretch of Pilsen with no gangways to separate buildings, no breathing room. The building was crammed, suffocated. Pilsen was crowded enough without angled streets thrown into the mix.

I can’t remember seeing anyone specific living there. I am sure there were children in there, old folks, laborers. It was a Pilsen flat. There were probably eight apartments, ten including the basement boiler room and attic space, which the landlord would have rented out for less than full rent. There was one front door. One center staircase, I’m sure, accessed by long hallways. It was a real tenement. The kind that had a common bathroom at one point. The kind of invisible building that you stepped into and disappeared. The kind of time-warp building that made people say “Damn, where have you been?” when they saw you back on the street.

I knew it was big. When my father and I stepped out of our building I could smell the cinder, strong and hard rather than soft and sweet. Black snowflakes were falling and the cold was sharp enough that I was relieved to climb into the car, which was still warm from my father’s drive home. My father said there was lots of equipment there already, and when we pulled up there were at least three ladder trucks, plus three pumper trucks. But the building was a lost cause. Flames were shooting through the windows. The roof had disintegrated, flames were flapping above the roofline. The white facade of the building stood out gray and dingy in the spotlights from the squad cars, the fire engines. Against the cold the fire seemed to bite even more. Each lick of fire seemed like a slice against the winter sky. And the water didn’t seem to help. Firefighters shot water through the windows. Up high there was a cannon shooting water down through what used to be the roof. But the fire kept on burning, blazing, like it wantedto burn. Or maybe it was Pilsen. Maybe Pilsen needed the burn, just for the heat.

The usual collection of victims with blankets, in nightgowns, pajamas, wasn’t there. Instead it was just us, the residents of Pilsen, the galley, some of us sitting in cars, some of us standing, steam highlighting our exhalations. Whoever was in the building was still in there, had to be, and as the minutes wore on a column of flame took hold. By the time we left, the building looked like a four-story jack-o’-lantern.

We went home, and while my father warmed up his dinner I climbed into bed. I knew he would not want to disturb my mother. That he would sleep on the couch and that my mother would wake up and our awkwardness as a family would continue for one more day. I could smell the fire, the charred wood, in my nose, on my arms, like I was burning, like I had been in the blaze myself. A building that tall and narrow was complicated to navigate even without fire. It was a wormhole, a building you stepped into and never came out of.

The next morning I awoke and found my father still asleep on the couch. I went to the table, got my bowl of puffed rice. I could still smell the blaze. My jacket was hanging on the chair but the smell was something stronger, like my father was also coated with it, the whole house, like the smell had finally become a part of all three of us.

“Did you guys go out last night?” my mother asked me.

“Yes,” I said.

“Which building was it?”

“The one across from the laundromat,” I said. “The tall one by Zemsky’s.”

“I never saw anyone go in there,” my mother answered.

“Me neither,” I said.

My mother and I exited our building out into the cold morning. We climbed into the car, the same one I had been in just a few hours before, though now it was cold, needing time to warm up. We drove down Eighteenth Street, turned onto Blue Island. There was the building, the shell of the building, coated in ice, transformed, glimmering, beautiful in the morning sun, an ice castle waiting to be occupied by anyone desperate enough to live there.