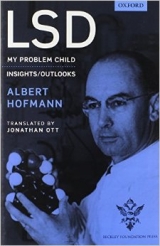

Текст книги "LSD — My Problem Child"

Автор книги: Albert Gofmann

Жанр:

Биографии и мемуары

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 7 (всего у книги 11 страниц)

Subjectively, I had no idea how long this condition had lasted. I felt my return to everyday reality to be a happy return from a strange, fantastic but quite real world to an old and familiar home.

This self-experiment showed once again that human beings react much more sensitively than animals to psychoactive substances. We had already reached the same conclusion in experimenting with LSD on animals, as described in an earlier chapter of this book. It was not inactivity of the mushroom material, but rather the deficient reaction capability of the research animals vis-à-vis such a type of active principle, that explained why our extracts had appeared inactive in the mouse and dog.

Because the assay on human subjects was the only test at our disposal for the detection of the active extract fractions, we had no other choice than to perform the testing on ourselves if we wanted to carry on the work and bring it to a successful conclusion. In the self-experiment just described, a strong reaction lasting several hours was produced by 2.4 g dried mushrooms. Therefore, in the sequel we used samples corresponding to only one-third of this amount, namely 0.8 g dried mushrooms. If these samples contained the active principle, they would only provoke a mild effect that impaired the ability to work for a short time, but this effect would still be so distinct that the inactive fractions and those containing the active principle could unequivocally be differentiated from one another. Several coworkers and colleagues volunteered as guinea pigs for this series of tests.

Psilocybin and Psilocin

With the help of this reliable test on human subjects, the active principle could be isolated, concentrated, and transformed into a chemically pure state by means of the newest separation methods. Two new substances, which I named psilocybin and psilocin, were thereby obtained in the form of colorless crystals.

These results were published in March 1958 in the journal Experientia, in collaboration with Professor Heim and with my colleagues Dr. A. Brack and Dr. H.

Kobel, who had provided greater quantities of mushroom material for these investigations after they had essentially improved the laboratory cultivation of the mushrooms.

Some of my coworkers at the time—Drs. A. J. Frey, H. Ott, T. Petrzilka, and F.

Troxler—then participated in the next steps of these investigations, the determination of the chemical structure of psilocybin and psilocin and the subsequent synthesis of these compounds, the results of which were published in the November 1958 issue of Experientia. The chemical structures of these mushroom factors deserve special attention in several respects. Psilocybin and psilocin belong, like LSD, to the indole compounds, the biologically important class of substances found in the plant and animal kingdoms.

Particular chemical features common to both the mushroom substances and LSD show that psilocybin and psilocin are closely related to LSD, not only with regard to psychic effects but also to their chemical structures. Psilocybin is the phosphoric acid ester of psilocin and, as such, is the first and hitherto only phosphoric-acid-containing indole compound discovered in nature. The phosphoric acid residue does not contribute to the activity, for the phosphoric-acid-free psilocin is just as active as psilocybin, but it makes the molecule more stable. While psilocin is readily decomposed by the oxygen in air, psilocybin is a stable substance.

Psilocybin and psilocin possess a chemical structure very similar to the brain factor serotonin. As was already mentioned in the chapter on animal experiments and biological research, serotonin plays an important role in the chemistry of brain functions. The two mushroom factors, like LSD, block the effects of serotonin in pharmacological experiments on different organs. Other pharmacological properties of psilocybin and psilocin are also similar to those of LSD. The main difference consists in the quantitative activity, in animal as well as human experimentation. The average active dose of psilocybin or psilocin in human beings amounts to 10 mg (0.01 g); accordingly, these two substances are more than 100 times less active than LSD, of which 0.1 mg constitutes a strong dose. Moreover, the effects of the mushroom factors last only four to six hours, much shorter than the effects of LSD (eight to twelve hours).

The total synthesis of psilocybin and psilocin, without the aid of the mushrooms, could be developed into a technical process, which would allow these substances to be produced on a large scale. Synthetic production is more rational and cheaper than extraction from the mushrooms.

Thus with the isolation and synthesis of the active principles, the demystification of the magic mushrooms was accomplished. The compounds whose wondrous effects led the Indians to believe for millennia that a god was residing in the mushrooms had their chemical structures elucidated and could be produced synthetically in flasks.

Just what progress in scientific knowledge was accomplished by natural products research in this case? Essentially, when all is said and done, we can only say that the mystery of the wondrous effects of teonanácatl was reduced to the mystery of the effects of two crystalline substances—since these effects cannot be explained by science either, but can only be describe.

A Voyage into the Universe of the Soul with Psilocybin

The relationship between the psychic effects of psilocybin and those of LSD, their visionaryhallucinatory character, is evident in the following report from Antaios, of a psilocybin experiment by Dr. Rudolf Gelpke. He has characterized his experiences with LSD and psilocybin, as already mentioned in a previous chapter, as "travels in the universe of the soul."

Where Time Stands Still

(10 mg psilocybin, 6 April 1961, 10:20)

After ca. 20 minutes, beginning effects: serenity, speechlessness, mild but pleasant dizzy sensation, and "pleasureful deep breathing."

10:50 Strong! dizziness, can no longer concentrate .

10:55 Excited, intensity of colors: everything pink to red.

11:05 The world concentrates itself there on the center of the table. Colors very intense.

11:10 A divided being, unprecedented—how can I describe this sensation of life?

Waves, different selves, must control me.

Immediately after this note I went outdoors, leaving the breakfast table, where I had eaten with Dr. H. and our wives, and lay down on the lawn. The inebriation pushed rapidly to its climax. Although I had firmly resolved to make constant notes, it now seemed to me a complete waste of time, the motion of writing infinitely slow, the possibilities of verbal expression unspeakably paltry – measured by the flood of inner experience that inundated me and threatened to burst me. It seemed to me that 100 years would not be sufficient to describe the fullness of experience of a single minute. At the beginning, optical impressions predominated: I saw with delight the boundless succession of rows of trees in the nearby forest. Then the tattered clouds in the sunny sky rapidly piled up with silent and breathtaking majesty to a superimposition of thousands of layers—heaven on heaven—and I waited then expecting that up there in the next moment something completely powerful, unheard of, not yet existing, would appear or happen -

would I behold a god? But only the expectation remained, the presentiment, this hovering, "on the threshold of the ultimate feeling." . . . Then I moved farther away (the proximity of others disturbed me) and lay down in a nook of the garden on a sun-warmed wood pile—my fingers stroked this wood with overflowing, animal-like sensual affection. At the same time I was submerged within myself; it was an absolute climax: a sensation of bliss pervaded me, a contented happiness—I found myself behind my closed eyes in a cavity full of brick-red ornaments, and at the same time in the "center of the universe of consummate calm." I knew everything was good—the cause and origins of everything was good. But at the same moment I also understood the suffering and the loathing, the depression and misunderstanding of ordinary life: there one is never "total,"

but instead divided, cut in pieces, and split up into the tiny fragments of seconds, minutes, hours, days, weeks, and years: there one is a slave of Moloch time, which devoured one piecemeal; one is condemned to stammering, bungling, and patchwork; one must drag about with oneself the perfection and absolute, the togetherness of all things; the eternal moment of the golden age, this original ground of being—that indeed nevertheless has always endured and will endure forever—there in the weekday of human existence, as a tormenting thorn buried deeply in the soul, as a memorial of a claim never fulfilled, as a fata morgana of a lost and promised paradise; through this feverish dream

"present" to a condemned "past" in a clouded "future." I understood. This inebriation was a spaceflight, not of the outer but rather of the inner man, and for a moment I experienced reality from a location that lies somewhere beyond the force of gravity of time.

As I began again to feel this force of gravity, I was childish enough to want to postpone the return by taking a new dose of 6 mg psilocybin at 11:45, and once again 4

mg at 14:30. The effect was trifling, and in any case not worth mentioning.

Mrs. Li Gelpke, an artist, also participated in this series of investigations, taking three self-experiments with LSD and psilocybin. The artist wrote of the drawing she made during the experiment:

Nothing on this page is consciously fashioned. While I worked on it, the memory (of the experience under psilocybin) was again reality, and led me at every stroke. For that reason the picture is as many-layered as this memory, and the figure at the lower right is really the captive of its dream.... When books about Mexican art came into my hands three weeks later, I again found the motifs of my visions there with a sudden start....

I have also mentioned the occurrence of Mexican motifs in psilocybin inebriation during my first self-experiment with dried Psilocybe mexicana mushrooms, as was described in the section on the chemical investigation of these mushrooms. The same phenomenon has also struck R. Gordon Wasson. Proceeding from such observations, he has advanced the conjecture that ancient Mexican art could have been influenced by visionary images, as they appear in mushroom inebriation.

The "Magic Morning Glory" Ololiuhqui

After we had managed to solve the riddle of the sacred mushroom teonanácatl in a relatively short time, I also became interested in the problem of another Mexican magic drug not yet chemically elucidated, ololiuhqui. Ololiuhqui is the Aztec name for the seeds of certain climbing plants (Convolvulaceae) that, like the mescaline cactus peyotl and the teonanácatl mushrooms, were used in pre-Columbian times by the Aztecs and neighboring people in religious ceremonies and magical healing practices. Ololiuhqui is still used even today by certain Indian tribes like the Zapotec, Chinantec, Mazatec, and Mixtec, who until a short time ago still led a genuinely isolated existence, little influenced by Christianity, in the remote mountains of southern Mexico.

An excellent study of the historical, ethnological, and botanical aspects of ololiuhqui was published in 1941 by Richard Evans Schultes, director of the Harvard Botanical Museum in Cambridge, Massachusetts. It is entitled "A Contribution to Our Knowledge of Rivea corymbosa, the Narcotic Ololiuqui of the Aztecs." The following statements about the history of ololiuhqui derive chiefly from Schultes's monograph. [Translator's note: As R. Gordon Wasson has pointed out, " ololiuhqui" is a more precise orthography than the more popular spelling used by Schultes. See Botanical Museum Leaflets Harvard University 20: 161-212, 1963.]

The earliest records about this drug were written by Spanish chroniclers of the sixteenth century, who also mentioned peyotl and teonanácatl. Thus the Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagun, in his already cited famous chronicle Historia General de las Cosas de Nueva Espana, writes about the wondrous effects of ololiuhqui: "There is an herb, called coatl xoxouhqui (green snake), which produces seeds that are called ololiuhqui. These seeds stupefy and deprive one of reason: they are taken as a potion."

We obtain further information about these seeds from the physician Francisco Hernandez, whom Philip II sent to Mexico from Spain, from 1570 to 1575, in order to study the medicaments of the natives. In the chapter "On Ololiuhqui" of his monumental work entitled Rerum Medicarum Novae Hispaniae Thesaurus seu Plantarum, Animalium Mineralium Mexicanorum Historia, published in Rome in 1651, he gives a detailed description and the first illustration of ololiuhqui. An extract from the Latin text accompanying the illustration reads in translation: " Ololiuhqui, which others call coaxihuitl or snake plant, is a climber with thin, green, heart-shaped leaves.... The flowers are white, fairly large.... The seeds are roundish. . . . When the priests of the Indians wanted to visit with the gods and obtain information from them, they ate of this plant in order to become inebriated. Thousands of fantastic images and demons then appeared to them...." Despite this comparatively good description, the botanical identification of ololiuhqui as seeds of Rivea corymbosa (L.) Hall. f. occasioned many discussions in specialist circles. Recently preference has been given to the synonym Turbina corymbosa (L.) Raf.

When I decided in 1959 to attempt the isolation o the active principles of ololiuhqui, only a single report on chemical work with the seeds of Turbina corymbosa was available. It was the work of the pharmacologist C. G. Santesson of Stockholm, from the year 1937. Santesson, however, was not successful in isolating an active substance in pure form.

Contradictory findings had been published about the activity of the ololiuhqui seeds.

The psychiatrist H. Osmond conducted a self-experiment with the seeds of Turbina corymbosa in 1955. After the ingestion of 60 to 100 seeds, he entered into a state of apathy and emptiness, accompanied by enhanced visual sensitivity. After four hours, there followed a period of relaxation and well-being, lasting for a longer time. The results of V. J. Kinross-Wright, published in England in 1958, in which eight voluntary research subjects, who had taken up to 125 seeds, perceived no effects at all, contradicted this report.

Through the mediation of R. Gordon Wasson, I obtained two samples of ololiuhqui seeds. In his accompanying letter of 6 August 1959 from Mexico City, he wrote of them:

. . . The parcels that I am sending you are the following: . . .

A small parcel of seeds that I take to be Rivea corymbosa, otherwise known as ololiuqui well-known narcotic of the Aztecs, called in Huautla "la semilla de la Virgen."

This parcel, you will find, consists of two little bottles, which represent two deliveries of seeds made to us in Huautla, and a larger batch of seeds delivered to us by Francisco Ortega "Chico," the Zapotec guide, who himself gathered the seeds from the plants at the Zapotec town of San Bartolo Yautepec....

The first-named, round, light brown seeds from Huautla proved in the botanical determination to have been correctly identified as Rivea (Turbina) corymbosa, while the black, angular seeds from San Bartolo Yautepec were identified as Ipomoea violacea L.

While Turbina corymbosa thrives only in tropical or subtropical climates, one also finds Ipomoea violacea as an ornamental plant dispersed over the whole earth in the temperate zones. It is the morning glory that delights the eye in our gardens in diverse varieties with blue or blue-red striped calyxes.

The Zapotec, besides the original ololiuhqui (that is, the seeds of Turbina corymbosa, which they call badoh), also utilize badoh negro, the seeds of Ipomoea violacea. T.

MacDougall, who furnished us with a second larger consignment of the last-named seeds, made this observation.

My capable laboratory assistant Hans Tscherter, with whom I had already carried out the isolation of the active principles of the mushrooms, participated in the chemical investigation of the ololiuhqui drug. We advanced the working hypothesis that the active principles of the ololiuhqui seeds could be representatives of the same class of chemical substances, the indole compounds, to which LSD, psilocybin, and psilocin belong.

Considering the very great number of other groups of substances that, like the indoles, were under consideration as active principles of ololiuhqui, it was indeed extremely improbable that this assumption would prove true. It could, however, very easily be tested. The presence of indole compounds, of course, may simply and rapidly be determined by colorimetric reactions. Thus even traces of indole substances, with a certain reagent, give an intense blue-colored solution.

We had luck with our hypothesis. Extracts of ololiuhqui seeds with the appropriate reagent gave the blue coloration characteristic of indole compounds. With the help of this colorimetric test, we succeeded in a short time in isolating the indole substances from the seeds and in obtaining them in chemically pure form. Their identification led to an astonishing result. What we found appeared at first scarcely believable. Only after repetition and the most careful scrutiny of the operations was our suspicion concerning the peculiar findings eliminated: the active principles from the ancient Mexican magic drug ololiuhqui proved to be identical with substances that were already present in my laboratory. They were identical with alkaloids that had been obtained in the course of the decades-long investigations of ergot; partly isolated as such from ergot, partly obtained through chemical modification of ergot substances.

Lysergic acid amide, lysergic acid hydroxyethylamide, and alkaloids closely related to them chemically were established as the main active principles of ololiuhqui. (See formulae in the appendix.) Also present was the alkaloid ergobasine, whose synthesis had constituted the starting point of my investigations on ergot alkaloids. Lysergic acid amide and lysergic acid hydroxyethylamide, active principles of ololiuhqui, are chemically very closely related to lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), which even for the non-chemist follows from the names.

Lysergic acid amide was described for the first time by the English chemists S. Smith and G. M. Timmis as a cleavage product of ergot alkaloids, and I had also produced this substance synthetically in the course of the investigations in which LSD originated.

Certainly, nobody at the time could have suspected that this compound synthesized in the flask would be discovered twenty years later as a naturally occurring active principle of an ancient Mexican magic drug.

After the discovery of the psychic effects of LSD, I had also tested lysergic acid amide in a self-experiment and established that it likewise evoked a dreamlike condition, but only with about a tenfold to twenty-fold greater dose than LSD. This effect was characterized by a sensation of mental emptiness and the unreality and meaninglessness of the outer world, by enhanced sensitivity of hearing, and by a not unpleasant physical lassitude, which ultimately led to sleep. This picture of the effects of LA-111, as lysergic acid amide was called as a research preparation, was confirmed in a systematic investigation by the psychiatrist Dr. H. Solms.

When I presented the findings of our investigations on ololiuhqui at the Natural Products Congress of the International Union for Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) in Sydney, Australia, in the fall of 1960, my colleagues received my talk with skepticism.

In the discussions following my lecture, some persons voiced the suspicion that the ololiuhqui extracts could well have been contaminated with traces of lysergic acid derivatives, with which so much work had been done in my laboratory.

There was another reason for the doubt in specialist circles concerning our findings.

The occurrence in higher plants (i.e., in the morning glory family) of ergot alkaloids that hitherto had been known only as constituents of lower fungi, contradicted the experience that certain substances are typical of and restricted to respective plant families. It is indeed a very rare exception to find a characteristic group of substances, in this case the ergot alkaloids, occurring in two divisions of the plant kingdom broadly separated in evolutionary history.

Our results were confirmed, however, when different laboratories in the United States, Germany, and Holland subsequently verified our investigations on the ololiuhqui seeds.

Nevertheless, the skepticism went so far that some persons even considered the possibility that the seeds could have been infected with alkaloid-producing fungi. That suspicion, however, was ruled out experimentally.

These studies on the active principles of ololiuhqui seeds, although they were published only in professional journals, had an unexpected sequel. We were apprised by two Dutch wholesale seed companies that their sale of seeds of Ipomoea violacea, the ornamental blue morning glory, had reached unusual proportions in recent times. They had heard that the great demand was connected with investigations of these seeds in our laboratory, about which they were eager to learn the details. It turned out that the new demand derived from hippie circles and other groups interested in hallucinogenic drugs.

They believed they had found in the ololiuhqui seeds a substitute for LSD, which was becoming less and less accessible.

The morning glory seed boom, however, lasted only a comparatively short time, evidently because of the undesirable experiences that those in the drug world had with this "new" ancient inebriant. The ololiuhqui seeds, which are taken crushed with water or another mild beverage, taste very bad and are difficult for the stomach to digest.

Moreover, the psychic effects of ololiuhqui, in fact, differ from those of LSD in that the euphoric and the hallucinogenic components are less pronounced, while a sensation of mental emptiness, often anxiety and depression, predominates. Furthermore, weariness and lassitude are hardly desirable effects as traits in an inebriant. These could all be reasons why the drug culture's interest in the morning glory seeds has diminished.

Only a few investigations have considered the question whether the active principles of ololiuhqui could find a useful application in medicine. In my opinion, it would be worthwhile to clarify above all whether the strong narcotic, sedative effect of certain ololiuhqui constituents, or of chemical modifications of these, is medicinally useful.

My studies in the field of hallucinogenic drugs reached a kind of logical conclusion with the investigations of ololiuhqui. They now formed a circle, one could almost say a magic circle: the starting point had been the synthesis of lysergic acid amides, among them the naturally occurring ergot alkaloid ergobasin. This led to the synthesis of lysergic acid diethylamide, LSD. The hallucinogenic properties of LSD were the reason why the hallucinogenic magic mushroom teonanácatl found its way into my laboratory. The work with teonanácatl, from which psilocybin and psilocin were isolated, proceeded to the investigation of another Mexican magic drug, ololiuhqui, in which hallucinogenic principles in the form of lysergic acid amides were again encountered, including ergobasin—with which the magic circle closed.

In Search of the Magic Plant "Ska María Pastora" in the Mazatec Country R. Gordon Wasson, with whom I had maintained friendly relations since the investigations of the Mexican magic mushrooms, invited my wife and me to take part in an expedition to Mexico in the fall of 1962. The purpose of the journey was to search for another Mexican magic plant. Wasson had learned on his travels in the mountains of southern Mexico that the expressed juice of the leaves of a plant, which were called hojas de la Pastora or hojas de María Pastora, in Mazatec ska Pastora or ska María Pastora (leaves of the shepherdess or leaves of Mary the shepherdess), were used among the Mazatec in medico-religious practices, like the teonanácatl mushrooms and the ololiuhqui seeds.

The question now was to ascertain from what sort of plant the "leaves of Mary the shepherdess" derived, and then to identify this plant botanically. We also hoped, if at all possible, to gather sufficient plant material to conduct a chemical investigation on the hallucinogenic principles it contained.

Ride through the Sierra Mazateca

On 26 September 1962, my wife and I accordingly flew to Mexico City, where we met Gordon Wasson. He had made all the necessary preparations for the expedition, so that in two days we had already set out on the next leg of the journey to the south. Mrs. Irmgard Weitlaner Johnson, (widow of Jean B. Johnson, a pioneer of the ethnographic study of the Mexican magic mushrooms, killed in the Allied landing in North Africa) had joined us. Her father, Robert J. Weitlaner, had emigrated to Mexico from Austria and had likewise contributed toward the rediscovery of the mushroom cult. Mrs. Johnson worked at the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City, as an expert on Indian textiles.

After a two-day journey in a spacious Land Rover, which took us over the plateau, along the snow-capped Popocatépetl, passing Puebla, down into the Valley of Orizaba with its magnificent tropical vegetation, then by ferry across the Popoloapan (Butterfly River), on through the former Aztec garrison Tuxtepec, we arrived at the starting point of our expedition, the Mazatec village of Jalapa de Diaz, lying on a hillside.

There we were in the midst of the environment and among the people that we would come to know in the succeeding 2 1/2 weeks.

There was an uproar upon our arrival in the marketplace, center of this village widely dispersed in the jungle. Old and young men, who had been squatting and standing around in the half-opened bars and shops, pressed suspiciously yet curiously about our Land Rover; they were mostly barefoot but all wore a sombrero. Women and girls were nowhere to be seen. One of the men gave us to understand that we should follow. him. He led us to the local president, a fat mestizo who had his office in a one-story house with a corrugated iron roof. Gordon showed him our credentials from the civil authorities and from the military governor of Oaxaca, which explained that we had come here to carry out scientific investigations. The president, who probably could not read at all, was visibly impressed by the large-sized documents equipped with official seals. He had lodgings assigned to us in a spacious shed, in which we could place our air mattresses and sleeping bags.

I looked around the region somewhat. The ruins of a large church from colonial times, which must have once been very beautiful, rose almost ghostlike in the direction of an ascending slope at the side of the village square. Now I could also see women looking out of their huts, venturing to examine the strangers. In their long, white dresses, adorned with red borders, and with their long braids of blue-black hair, they offered a picturesque sight.

We were fed by an old Mazatec woman, who directed a young cook and two helpers.

She lived in one of the typical Mazatec huts. These are simply rectangular structures with thatched gabled roofs and walls of wooden poles joined together, windowless, the chinks between the wooden poles offering sufficient opportunity to look out. In the middle of the hut, on the stamped clay floor, was an elevated, open fireplace, built up out of dried clay or made of stones. The smoke escaped through large openings in the walls under the two ends of the roof. Bast mats that lay in a corner or along the walls served as beds. The huts were shared with the domestic animals, as well as black swine, turkeys, and chickens.

There was roasted chicken to eat, black beans, and also, in place of bread, tortillas, a type of cornmeal pancake that is baked on the hot stone slab of the hearth. Beer and tequila, an Agave liquor, were served.

Next morning our troop formed for the ride through the Sierra Mazateca. Mules and guides were engaged from the horsekeeper of the village. Guadelupe, the Mazatec familiar with the route, took charge of guiding the lead animal. Gordon, Irmgard, my wife, and I were stationed on our mules in the middle. Teodosio and Pedro, called Chico, two young fellows who trotted along barefoot beside the two mules laden with our baggage, brought up the rear.

It took some time to get accustomed to the hard wooden saddles. Then, however, this mode of locomotion proved to be the most ideal type of travel that I know of. The mules followed the leader, single file, at a steady pace. They required no direction at all by the rider. With surprising dexterity, they sought out the best spots along the almost impassable, partly rocky, partly marshy paths, which led through thickets and streams or onto precipitous slopes. Relieved of all travel cares, we could devote all our attention to the beauty of the landscape and the tropical vegetation. There were tropical forests with gigantic trees overgrown with twining plants, then again clearings with banana groves or coffee plantations, between light stands of trees, flowers at the edge of the path, over which wondrous butterflies bustled about.... We made our way upstream along the broad riverbed of Rio Santo Domingo, with brooding heat and steamy air, now steeply ascending, then again falling. During a short, violent tropical downpour, the long broad ponchos of oilcloth, with which Gordon had equipped us, proved quite useful. Our Indian guides had protected themselves from the cloudburst with gigantic, heart-shaped leaves that they nimbly chopped off at the edge of the path. Teodosio and Chico gave the impression of great, green hay cricks as they ran, covered with these leaves, beside their mules.