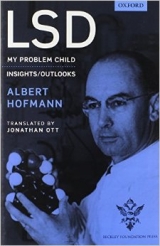

Текст книги "LSD — My Problem Child"

Автор книги: Albert Gofmann

Жанр:

Биографии и мемуары

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 4 (всего у книги 11 страниц)

It was obvious that a substance with such fantastic effects on mental perception and on the experience of the outer and inner world would also arouse interest outside medical science, but I had not expected that LSD, with its unfathomably uncanny, profound effects, so unlike the character of a recreational drug, would ever find worldwide use as an inebriant. I had expected curiosity and interest on the part of artists outside of medicine—performers, painters, and writers—but not among people in general. After the scientific publications around the turn of the century on mescaline—which, as already mentioned, evokes psychic effects quite like those of LSD—the use of this compound remained confined to medicine and to experiments within artistic and literary circles. I had expected the same fate for LSD. And indeed, the first non-medicinal self-experiments with LSD were carried out by writers, painters, musicians, and other intellectuals.

LSD sessions had reportedly provoked extraordinary aesthetic experiences and granted new insights into the essence of the creative process. Artists were influenced in their creative work in unconventional ways. A particular type of art developed that has become known as psychedelic art. It comprises creations produced under the influenced of LSD

and other psychedelic drugs, whereby the drugs acted as stimulus and source of inspiration. The standard publication in this field is the book by Robert E. L. Masters and Jean Houston, Psychedelic Art (Balance House, 1968). Works of psychedelic art are not created while the drug is in effect, but only afterward, the artist being inspired by these experiences. As long as the inebriated condition lasts, creative activity is impeded, if not completely halted. The influx of images is too great and is increasing too rapidly to be portrayed and fashioned. An overwhelming vision paralyzes activity. Artistic productions arising directly from LSD inebriation, therefore, are mostly rudimentary in character and deserve consideration not because of their artistic merit, but because they are a type of psychoprogram, which offers insight into the deepest mental structures of the artist, activated and made conscious by LSD. This was demonstrated later in a large-scale experiment by the Munich psychiatrist Richard P. Hartmann, in which thirty famous painters took part. He published the results in his book Malerei aus Bereichen des Unbewussten: Kunstler Experimentieren unter LSD [Painting from spheres of the unconscious: artists experiment with LSD], Verlag M. Du Mont Schauberg, Cologne, 1974).

LSD experiments also gave new impetus to exploration into the essence of religious and mystical experience. Religious scholars and philosophers discussed the question whether the religious and mystical experiences often discovered in LSD sessions were genuine, that is, comparable to spontaneous mysticoreligious enlightenment.

This nonmedicinal yet earnest phase of LSD research, at times in parallel with medicinal research, at times following it, was increasingly overshadowed at the beginning of the 1960s, as LSD use spread with epidemic-like speed through all social classes, as a sensational inebriating drug, in the course of the inebriant mania in the United States. The rapid rise of drug use, which had its beginning in this country about twenty years ago, was not, however, a consequence of the discovery of LSD, as superficial observers often declared. Rather it had deep-seated sociological causes: materialism, alienation from nature through industrialization and increasing urbanization, lack of satisfaction in professional employment in a mechanized, lifeless working world, ennui and purposelessness in a wealthy, saturated society, and lack of a religious, nurturing, and meaningful philosophical foundation of life.

The existence of LSD was even regarded by the drug enthusiasts as a predestined coincidence—it had to be discovered precisely at this time in order to bring help to people suffering under the modern conditions. It is not surprising that LSD first came into circulation as an inebriating drug in the United States, the country in which industrialization, urbanization, and mechanization, even of agriculture, are most broadly advanced. These are the same factors that have led to the origin and growth of the hippie movement that developed simultaneously with the LSD wave. The two cannot be dissociated. It would be worth investigating to what extent the consumption of psychedelic drugs furthered the hippie movement and conversely.

The spread of LSD from medicine and psychiatry into the drug scene was introduced and expedited by publications on sensational LSD experiments that, although they were carried out in psychiatric clinics and universities, were not then reported in scientific journals, but rather in magazines and daily papers, greatly elaborated. Reporters made themselves available as guinea pigs. Sidney Katz, for example, participated in an LSD

experiment in the Saskatchewan Hospital in Canada under the supervision of noted psychiatrists; his experiences, however, were not published in a medical journal. Instead, he described them in an article entitled "My Twelve Hours as a Madman" in his magazine MacLean's Canada National Magazine, colorfully illustrated in fanciful fullness of detail.

The widely distributed German magazine Quick, in its issue number 12 of 21 March 1954, reported a sensational eyewitness account on "Ein kuhnes wissenschaftliches Experiment" [a daring scientific experiment] by the painter Wilfried Zeller, who took "a few drops of lysergic acid" in the Viennese University Psychiatric Clinic. Of the numerous publications of this type that have made effective lay propaganda for LSD, it is sufficient to cite just one more example: a large-scale, illustrated article in Look magazine of September 1959. Entitled "The Curious Story Behind the New Cary Grant," it must have contributed enormously to the diffusion of LSD consumption. The famous movie star had received LSD in a respected clinic in California, in the course of a psychotherapeutic treatment. He informed the Look reporter that he had sought inner peace his whole life long, but yoga, hypnosis, and mysticism had not helped him. Only the treatment with LSD had made a new, self-strengthened man out of him, so that after three frustrating marriages he now believed himself really able to love and make a woman happy.

The evolution of LSD from remedy to inebriating drug was, however, primarily promoted by the activities of Dr. Timothy Leary and Dr. Richard Alpert of Harvard University. In a later section I will come to speak in more detail about Dr. Leary and my meetings with this personage who has become known worldwide as an apostle of LSD.

Books also appeared on the U.S. market in which the fantastic effects of LSD were reported more fully. Here only two of the most important will be mentioned: Exploring Inner Space by Jane Dunlap (Harcourt Brace and World, New York, 1961) and My Self and I by Constance A. Newland (N A.L. Signet Books, New York, 1963). Although in both cases LSD was used within the scope of a psychiatric treatment, the authors addressed their books, which became bestsellers, to the broad public. In her book, subtitled "The Intimate and Completely Frank Record of One Woman's Courageous Experiment with Psychiatry's Newest Drug, LSD 25," Constance A. Newland described in intimate detail how she had been cured of frigidity. After such avowals, one can easily imagine that many people would want to try the wondrous medicine for themselves. The mistaken opinion created by such reports– that it would be sufficient simply to take LSD

in order to accomplish such miraculous effects and transformations in oneself—soon led to broad diffusion of self-experimentation with the new drug.

Objective, informative books about LSD and its problems also appeared, such as the excellent work by the psychiatrist Dr. Sidney Cohen, The Beyond Within (Atheneum, New York, 1967), in which the dangers of careless use are clearly exposed. This had, however, no power to put a stop to the LSD epidemic.

As LSD experiments were often carried out in ignorance of the uncanny, unforeseeable, profound effects, and without medical supervision, they frequently came to a bad end. With increasing LSD consumption in the drug scene, there came an increase in "horror trips"—LSD experiments that led to disoriented conditions and panic, often resulting in accidents and even crime.

The rapid rise of nonmedicinal LSD consumption at the beginning of the 1960s was also partly attributable to the fact that the drug laws then current in most countries did not include LSD. For this reason, drug habitués changed from the legally proscribed narcotics to the still-legal substance LSD. Moreover, the last of the Sandoz patents for the production of LSD expired in 1963, removing a further hindrance to illegal manufacture of the drug.

The rise of LSD in the drug scene caused our firm a nonproductive, laborious burden.

National control laboratories and health authorities requested statements from us about chemical and pharmacological properties, stability and toxicity of LSD, and analytical methods for its detection in confiscated drug samples, as well as in the human body, in blood and urine. This brought a voluminous correspondence, which expanded in connection with inquiries from all over the world about accidents, poisonings, criminal acts, and so forth, resulting from misuse of LSD. All this meant enormous, unprofitable difficulties, which the business management of Sandoz regarded with disapproval. Thus it happened one day that Professor Stoll, managing director of the firm at the time, said to me reproachfully: "I would rather you had not discovered LSD."

At that time, I was now and again assailed by doubts whether the valuable pharmacological and psychic effects of LSD might be outweighed by its dangers and by possible injuries due to misuse. Would LSD become a blessing for humanity, or a curse?

This I often asked myself when I thought about my problem child. My other preparations, Methergine, Dihydroergotamine, and Hydergine, caused me no such problems and difficulties. They were not problem children; lacking extravagant properties leading to misuse, they have developed in a satisfying manner into therapeutically valuable medicines.

The publicity about LSD attained its high point in the years 1964 to 1966, not only with regard to enthusiastic claims about the wondrous effects of LSD by drug fanatics and hippies, but also to reports of accidents, mental breakdowns, criminal acts, murders, and suicide under the influence of LSD. A veritable LSD hysteria reigned.

Sandoz Stops LSD Distribution

In view of this situation, the management of Sandoz was forced to make a public statement on the LSD problem and to publish accounts of the corresponding measures that had been taken. The pertinent letter, dated 23 August 1965, by Dr. A. Cerletti, at the time director of the Pharmaceutical Department of Sandoz, is reproduced below: Decision Regarding LSD 25 and Other Hallucinogenic Substances

More than twenty years have elapsed since the discovery by Albert Hofmann of LSD

25 in the SANDOZ Laboratories. Whereas the . fundamental importance of this discovery may be assessed by its impact on the development of modern psychiatric research, it must be recognized that it placed a heavy burden of responsibility on SANDOZ, the owner of this product.

The finding of a new chemical with outstanding biological properties, apart from the scientific success implied by its synthesis, is usually the first decisive step toward profitable development of a new drug. In the case of LSD, however, it soon became clear that, despite the outstanding properties of this compound, or rather because of the very nature of these qualities, even though LSD was fully protected by SANDOZ-owned patents since the time of its first synthesis in 1938, the usual means of practical exploitation could not be envisaged.

On the other hand, all the evidence obtained following the initial studies in animals and humans carried out in the SANDOZ research laboratories pointed to the important role that this substance could play as an investigational tool in neurological research and in psychiatry.

It was therefore decided to make LSD available free of charge to qualified experimental and clinical investigators all over the world. This broad research approach was assisted by the provision of any necessary technical aid and in many instances also by financial support.

An enormous amount of scientific documents, published mainly in the international biochemical and medical literature and systematically listed in the "SANDOZ

Bibliography on LSD" as well as in the "Catalogue of Literature on Delysid" periodically edited by SANDOZ, gives vivid proof of what has been achieved by following this line of policy over nearly two decades. By exercising this kind of "nobile officium" in accordance with the highest standards of medical ethics with all kinds of self-imposed precautions and restrictions, it was possible for many years to avoid the danger of abuse (i.e., use by people neither competent nor qualified), which is always inherent in a compound with exceptional CNS activity.

In spite of all our precautions, cases of LSD abuse have occurred from time to time in varying circumstances completely beyond the control of SANDOZ. Very recently this danger has increased considerably and in some parts of the world has reached the scale of a serious threat to public health. This state of affairs has now reached a critical point for the following reasons: (1) A worldwide spread of misconceptions of LSD has been caused by an increasing amount of publicity aimed at provoking an active interest in laypeople by means of sensational stories and statements; (2) In most countries no adequate legislation exists to control and regulate the production and distribution of substances like LSD; (3) The problem of availability of LSD, once limited on technical grounds, has fundamentally changed with the advent of mass production of lysergic acid by fermentation procedures. Since the last patent on LSD expired in 1963, it is not surprising to find that an increasing number of dealers in fine chemicals are offering LSD

from unknown sources at the high price known to be paid by LSD fanatics.

Taking into consideration all the above-mentioned circumstances and the flood of requests for LSD which has now become uncontrollable, the pharmaceutical management of SANDOZ has decided to stop immediately all further production and distribution of LSD. The same policy will apply to all derivatives or analogues of LSD with hallucinogenic properties as well as to Psilocybin, Psilocin, and their hallucinogenic congeners.

For a while the distribution of LSD and psilocybin was stopped completely by Sandoz.

Most countries had subsequently proclaimed strict regulations concerning possession, distribution, and use of hallucinogens, so that physicians, psychiatric clinics, and research institutes, if they could produce a special permit to work with these substances from the respective national health authorities, could again be supplied with LSD and psilocybin.

In the United States the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) undertook the distribution of these agents to licensed research institutes.

All these legislative and official precautions, however, had little influence on LSD

consumption in the drug scene, yet on the other hand hindered and continue to hinder medicinal-psychiatric use and LSD research in biology and neurology, because many researchers dread the red tape that is connected with the procurement of a license for the use of LSD. The bad reputation of LSD—its depiction as an "insanity drug" and a

"satanic invention" – constitutes a further reason why many doctors shunned use of LSD

in their psychiatric practice.

In the course of recent years the uproar of publicity about LSD has quieted, and the consumption of LSD as an inebriant has also diminished, as far as that can be concluded from the rare reports about accidents and other regrettable occurrences following LSD

ingestion. It may be that the decrease of LSD accidents, however, is not simply due to a decline in LSD consumption. Possibly the recreational users, with time, have become more aware of the particular effects and dangers of LSD and more cautious in their use of this drug. Certainly LSD, which was for a time considered in the Western world, above all in the United States, to be the number-one inebriant, has relinquished this leading role to other inebriants such as hashish and the habituating, even physically destructive drugs like heroin and amphetamine. The last-mentioned drugs represent an alarming sociological and public health problem today.

Dangers of Nonmedicinal LSD Experiments

While professional use of LSD in psychiatry entails hardly any risk, the ingestion of this substance outside of medical practice, without medical supervision, is subject to multifarious dangers. These dangers reside, on the one hand, in external circumstances connected with illegal drug use and, on the other hand, in the peculiarity of LSD's psychic effects.

The advocates of uncontrolled, free use of LSD and other hallucinogens base their attitude on two claims: (l) this type of drug produces no addiction, and (2) until now no danger to health from moderate use of hallucinogens has been demonstrated. Both are true. Genuine addiction, characterized by the fact that psychic and often severe physical disturbances appear on withdrawal of the drug, has not been observed, even in cases in which LSD was taken often and over a long period of time. No organic injury or death as a direct consequence of an LSD intoxication has yet been reported. As discussed in greater detail in the chapter "LSD in Animal Experiments and Biological Research," LSD

is actually a relatively nontoxic substance in proportion to its extraordinarily high psychic activity.

Psychotic Reactions

Like the other hallucinogens, however, LSD is dangerous in an entirely different sense.

While the psychic and physical dangers of the addicting narcotics, the opiates, amphetamines, and so forth, appear only with chronic use, the possible danger of LSD

exists in every single experiment. This is because severe disoriented states can appear during any LSD inebriation. It is true that through careful preparation of the experiment and the experimenter such episodes can largely be avoided, but they cannot be excluded with certainty. LSD crises resemble psychotic attacks with a manic or depressive character.

In the manic, hyperactive condition, the feeling of omnipotence or invulnerability can lead to serious casualties. Such accidents have occurred when inebriated persons confused in this way—believing themselves to be invulnerable—walked in front of a moving automobile or jumped out a window in the belief that they were able to fly. This type of LSD casualty, however, is not so common as one might be led to think on the basis of reports that were sensationally exaggerated by the mass media. Nevertheless, such reports must serve as serious warnings.

On the other hand, a report that made the rounds worldwide, in 1966, about an alleged murder committed under the influence on LSD, cannot be true. The suspect, a young man in New York accused of having killed his mother-in-law, explained at his arrest, immediately after the fact, that he knew nothing of the crime and that he had been on an LSD trip for three days. But an LSD inebriation, even with the highest doses, lasts no longer than twelve hours, and repeated ingestion leads to tolerance, which means that extra doses are ineffective. Besides, LSD inebriation is characterized by the fact that the person remembers exactly what he or she has experienced. Presumably the defendant in this case expected leniency for extenuating circumstances, owing to unsoundness of mind.

The danger of a psychotic reaction is especially great if LSD is given to someone without his or her knowledge. This was demonstrated in an episode that took place soon after the discovery of LSD, during the first investigations with the new substance in the Zurich University Psychiatric Clinic, when people were not yet aware of the danger of such jokes. A young doctor, whose colleagues had slipped LSD into his coffee as a lark, wanted to swim across Lake Zurich during the winter at -20!C (-4!F) and had to be prevented by force.

There is a different danger when the LSD-induced disorientation exhibits a depressive rather than manic character. In the course of such an LSD experiment, frightening visions, death agony, or the fear of becoming insane can lead to a threatening psychic breakdown or even to suicide. Here the LSD trip becomes a "horror trip."

The demise of a Dr. Olson, who had been given LSD without his knowledge in the course of U.S. Army drug experiments, and who then committed suicide by jumping from a window, caused a particular sensation. His family could not understand how this quiet, well-adjusted man could have been driven to this deed. Not until fifteen years later, when the secret documents about the experiments were published, did they learn the true circumstances, whereupon the president of the United States publicly apologized to the dependents.

The conditions for the positive outcome of an LSD experiment, with little possibility of a psychotic derailment, reside on the one hand in the individual and on the other hand in the external milieu of the experiment. The internal, personal factors are called set, the external conditions setting.

The beauty of a living room or of an outdoor location is perceived with particular force because of the highly stimulated sense organs during LSD inebriation, and such an amenity has a substantial influence on the course of the experiment. The persons present, their appearance, their traits, are also part of the setting that determines the experience.

The acoustic milieu is equally significant. Even harmless noises can turn to torment, and conversely lovely music can develop into a euphoric experience. With LSD experiments in ugly or noisy surroundings, however, there is greater danger of a negative outcome, including psychotic crises. The machine– and appliance-world of today offers much scenery and all types of noise that could very well trigger panic during enhanced sensibility.

Just as meaningful as the external milieu of the LSD experience, if not even more important, is the mental condition of the experimenters, their current state of mind, their attitude to the drug experience, and their expectations associated with it. Even unconscious feelings of happiness or fear can have an effect. LSD tends to intensify the actual psychic state. A feeling of happiness can be heightened to bliss, a depression can deepen to despair. LSD is thus the most inappropriate means imaginable for curing a depressive state. It is dangerous to take LSD in a disturbed, unhappy frame of mind, or in a state of fear. The probability that the experiment will end in a psychic breakdown is then quite high.

Among persons with unstable personality structures, tending to psychotic reactions, LSD experimentation ought to be completely avoided. Here an LSD shock, by releasing a latent psychosis, can produce a lasting mental injury.

The psyche of very young persons should also be considered as unstable, in the sense of not yet having matured. In any case, the shock of such a powerful stream of new and strange perceptions and feelings, such as is engendered by LSD, endangers the sensitive, still-developing psycho-organism. Even the medicinal use of LSD in youths under eighteen years of age, in the scope of psychoanalytic or psychotherapeutic treatment, is discouraged in professional circles, correctly so in my opinion. Juveniles for the most part still lack a secure, solid relationship to reality. Such a relationship is needed before the dramatic experience of new dimensions of reality can be meaningfully integrated into the world view. Instead of leading to a broadening and deepening of reality consciousness, such an experience in adolescents will lead to insecurity and a feeling of being lost. Because of the freshness of sensory perception in youth and the still-unlimited capacity for experience, spontaneous visionary experiences occur much more frequently than in later life. For this reason as well, psychostimulating agents should not be used by juveniles.

Even in healthy, adult persons, even with adherence to all of the preparatory and protective measures discussed, an LSD experiment can fail, causing psychotic reactions.

Medical supervision is therefore earnestly to be recommended, even for nonmedicinal LSD experiments. This should include an examination of the state of health before the experiment. The doctor need not be present at the session; however, medical help should at all times be readily available.

Acute LSD psychoses can be cut short and brought under control quickly and reliably by injection of chlorpromazine or another sedative of this type.

The presence of a familiar person, who can request medical help in the event of an emergency, is also an indispensable psychological assurance. Although the LSD

inebriation is characterized mostly by an immersion in the individual inner world, a deep need for human contact sometimes arises, especially in depressive phases.

LSD from the Black Market

Nonmedicinal LSD consumption can bring dangers of an entirely different type than hitherto discussed: for most of the LSD offered in the drug scene is of unknown origin.

LSD preparations from the black market are unreliable when it comes to both quality and dosage. They rarely contain the declared quantity, but mostly have less LSD, often none at all, and sometimes even too much. In many cases other drugs or even poisonous substances are sold as LSD. These observations were made in our laboratory upon analysis of a great number of LSD samples from the black market. They coincide with the experiences of national drug control departments.

The unreliability in the strength of LSD preparations on the illicit drug market can lead to dangerous overdosage. Overdoses have often proved to be the cause of failed LSD

experiments that led to severe psychic and physical breakdowns. Reports of alleged fatal LSD poisoning, however, have yet to be confirmed. Close scrutiny of such cases invariably established other causative factors.

The following case, which took place in 1970, is cited as an example of the possible dangers of black market LSD. We received for investigation from the police a drug powder distributed as LSD. It came from a young man who was admitted to the hospital in critical condition and whose friend had also ingested this preparation and died as a result. Analysis showed that the powder contained no LSD, but rather the very poisonous alkaloid strychnine.

If most black market LSD preparations contained less than the stated quantity and often no LSD at all, the reason is either deliberate falsification or the great instability of this substance. LSD is very sensitive to air and light. It is oxidatively destroyed by the oxygen in the air and is transformed into an inactive substance under the influence of light. This must be taken into account during the synthesis and especially during the production of stable, storable forms of LSD. Claims that LSD may easily be prepared, or that every chemistry student in a half-decent laboratory is capable of producing it, are untrue. Procedures for synthesis of LSD have indeed been published and are accessible to everyone. With these detailed procedures in hand, chemists would be able to carry out the synthesis, provided they had pure lysergic acid at their disposal; its possession today, however, is subject to the same strict regulations as LSD. In order to isolate LSD in pure crystalline form from the reaction solution and in order to produce stable preparations, however, special equipment and not easily acquired specific experience are required, owing (as stated previously) to the great instability of this substance.

Only in completely oxygen-free ampules protected from light is LSD absolutely stable.

Such ampules, containing 100 µg (= 0.1 mg) LSD-tartrate (tartaric acid salt of LSD) in 1

cc of aqueous solution, were produced for biological research and medicinal use by the Sandoz firm. LSD in tablets prepared with additives that inhibit oxidation, while not absolutely stable, at least keeps for a longer time. But LSD preparations often found on the black market—LSD that has been applied in solution onto sugar cubes or blotting paper—decompose in the course of weeks or a few months.

With such a highly potent substance as LSD, the correct dosage is of paramount importance. Here the tenet of Paracelsus holds good: the dose determines whether a substance acts as a remedy or as a poison. A controlled dosage, however, is not possible with preparations from the black market, whose active strength is in no way guaranteed.

One of the greatest dangers of non-medicinal LSD experiments lies, therefore, in the use of such preparations of unknown provenience.

The Case of Dr. Leary

Dr. Timothy Leary, who has become known worldwide in his role of drug apostle, had an extraordinarily strong influence on the diffusion of illegal LSD consumption in the United States. On the occasion of a vacation in Mexico in the year 1960, Leary had eaten the legendary "sacred mushrooms," which he had purchased from a shaman. During the mushroom inebriation he entered into a state of mystico-religious ecstasy, which he described as the deepest religious experience of his life. From then on, Dr. Leary, who at the time was a lecturer in psychology at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, dedicated himself totally to research on the effects and possibilities of the use of psychedelic drugs. Together with his colleague Dr. Richard Alpert, he started various research projects at the university, in which LSD and psilocybin, isolated by us in the meantime, were employed.