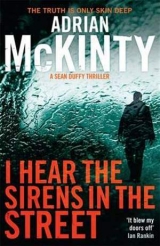

Текст книги "I Hear the Sirens in the Street"

Автор книги: Adrian McKinty

Жанры:

Триллеры

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 9 (всего у книги 19 страниц)

Larne RUC.

With one of their own gunned down, the atmosphere was apocalyptic and doom laden. We paid our respects to the duty sergeant and ostentatiously put a few coppers in the widows and orphans box.

We met with the Superintendent, expressed our condolences, told him that we wanted to look into Dougherty’s old cases and Tony explained that this was nothing more than Standard Operating Procedure.

The Super couldn’t have cared less. He was new on the job, had barely interacted with Dougherty and now he had a funeral to suss and with the Chief Constable and half a dozen VIPs coming it was going to be a friggin’ nightmare.

We left him to his drama and found Dougherty’s office.

A shining twenty-three-year-old detective constable called Conlon showed us in. I asked him to hang around to answer questions while Tony looked through Dougherty’s files.

“Was Inspector Dougherty a family man?” I asked conversationally.

“Wife and a grown daughter. Ex-wife. He was divorced.”

“Where’s she? The wife, I mean.”

“Wife and daughter are both over the water, I gathered.”

“Whereabouts?”

“I don’t know. London somewhere?”

“Was he a social man – did you all go out for drinks come a Friday night?”

Conlon hesitated, torn between loyalty to the dead man and a desire to tell me how it was.

“Inspector Dougherty wasn’t exactly a social drinker. When he drank, he drank, if you catch my meaning.”

“I catch your meaning. Was he the senior detective here?”

“Detective Chief Inspector Canning is the senior detective here. He’s in court today, I could try and page him?”

“No, no, you’ll be fine. Tell me more about Inspector Dougherty; what sort of a man was he?”

“What do you mean?”

“Friendly, dour, a practical joker, what?”

“Well, he was, uh, sort of semi-retired, so he was. Nobody really … I didn’t have much to do with him.”

“Was he working on anything in particular in the last couple of days?” I asked.

“I thought this was all a random IRA hit?” Conlon asked suspiciously.

“It was a random IRA hit,” Tony said, looking up from the filing cabinet.

“Did Dougherty mention any threats or anything that was troubling him?”

“Not to me.”

“To anybody else?”

“Not that I’m aware of.”

“What was he working on the last few days?”

“I didn’t know him very well,” he said, hesitated, and looked out the window.

“You don’t want to speak ill of the dead … is that the vibe I’m catching here?” I asked him.

DC Conlon reddened, gave a little half nod and said nothing.

“The Inspector didn’t do much but come in late, sit in his office, drink, leave early, drive home half drunk, is that it?” I wondered.

DC Conlon nodded again.

“But what about the last couple of days? Did he seem different? More fired up? Onto anything?”

“Not so I’d noticed,” Conlon said.

“Nothing out of the ordinary at all?”

Conlon shook his head. His hair seemed to move independently of his head when he did that and it made him look particularly stupid.

“How did he get assigned to the McAlpine murder if he was such a bloody lightweight?” I asked.

“Chief Inspector Canning was in for his appendix,” Conlon said.

“And after he came back from his appendix?”

“Well, that was an open and shut case, wasn’t it?”

“It’s hardly shut, son, is it? No prosecutions, no convictions?”

Conlon coughed. “What I mean is, I mean, we know who done it, don’t we?”

“Do we? Who done it? Gimme their names and I’ll have them fuckers in the cells within the hour,” I said.

“I mean, we know who done it in the corporate sense. The IRA killed him.”

“The corporate sense is it now? The IRA did it. Just like they killed Dougherty himself.”

“Well, didn’t they?” Conlon asked.

“Yes, they did,” Tony said. He waved a file at me.

I looked at Conlon. “That’ll be all. And do us a favour, mate, keep your mouth shut.”

“About what?”

“Exactly. Now fuck off.”

He exited the office and I closed the door.

“What did you find, mate?” I asked Tony.

“Nothing of interest in any of them. Dougherty has nothing in his ‘active’ file and there’s a layer of dust on everything else.”

“I take it that’s the McAlpine file?”

He slid it across the table to me.

The last notes on it had been made in December. He’d added nothing since my visit.

I shook my head. Tony squeezed my arm again. “Everybody can’t be as impressed by you as I am, mate. I’m afraid you didn’t wow Dougherty as much as you would have liked.”

“I suppose not.”

Tony was almost laughing now. “Maybe you should have worn your medal or told him about that time you met Joey Ramone.”

“All right, all right. No point in raking me. Let’s skedaddle.”

We straightened the desk, closed the filing cabinets.

“And look, if you find a case notebook in the house or the car or anything, I’d be keen to take a look at it,” I said to Tony.

“You got it, mate,” Tony assured me.

“And I did see Joey Ramone, he was right across from me in the subway.”

“Big stars don’t ride the fucking subway.”

We had almost made it out of the incident room when young Conlon approached us diffidently. “Yes?” Tony wondered.

“Well, it’s probably nothing.”

“Go on,” I said encouragingly.

“There was one thing that was a wee bit of the ordinary,” Conlon began.

“What was it?” I asked, my heart rate quickening.

“Well, Dougherty knows that I’m from Islandmagee, doesn’t he? And he knows that I take the ferry over here every morning, instead of driving round through Whitehead. It saves you twenty minutes.”

“Go on.”

“Well, I suppose that’s why he asked me how much it cost.”

“He asked you how much the ferry cost from Larne to Islandmagee?”

“Aye.”

“And that was strange, was it?” Tony asked.

“A wee bit. Because he hadn’t spoken to me at all this year. You know?”

I looked at Tony. “He was going to take the ferry over to Islandmagee and he wanted to check the price.”

Tony nodded.

“Did he say anything else?” I asked.

“Nope. I told him it was twenty pence for pedestrians and a quid for cars. And he thanked me and that was that.”

I looked at Tony. He gave me a half nod.

“You done good, son,” I told DC Conlon.

Tony and I did the rounds, said hello to a couple of sergeants and left the station. We got in the Beemer and headed out into the street.

“When he investigated McAlpine’s murder he would have had a driver. He would have gone over there in a police Land Rover the long way round through Whitehead. But he was going over himself in his own car,” Tony said.

“Going to question Mrs McAlpine,” I said.

“Possibly. What time is it?”

I looked at my watch. “Nine thirty.”

“I feel like that ad for the army: ‘We do more things before breakfast than you’ll do all day.’”

“Aye, more stupid things.”

“Yeah.”

“Shall we go do one more stupid thing?”

“Aye.”

I drove the Land Rover down into Larne and easily found the ferry over the Lough to Islandmagee. We paid the money and drove on. It left on the half hour and five minutes later we docked in Ballylumford, Islandmagee. “Let’s go see what alibi this bint of yours has cooked up for her whereabouts last night,” Tony said.

15: SIR HARRY

I drove the car over the cattle grid and up the lane marked “Private Road No Entry”.

“What’s all this?” Tony asked, pointing out the window.

“It’s a private road on private land.”

“The IRA drove all the way up here on private land just to murder this woman’s husband?” Tony asked.

“That’s what we’re supposed to believe.”

“Well, I’ve seen stranger things.”

“Me too.”

The trail wound on, over a hill and down into the boggy valley.

Tony sighed. “So, what about you, Sean? I haven’t really seen you since the hospital.”

“I’m okay. What about you? How’s the missus? Any kids on the way?”

“Nah, not yet. She’s keen as mustard but I’d rather wait until, uh, we’re more settled. You can’t bring kids up in a place like this…What about you and yon nurse lady?”

“Doctor lady. She’s gone. Over the water.”

“Over the water? Well, you can’t blame her, can you?”

“No. You can’t.”

“Hopefully that’ll be me in about a year. Then we can do kids, mortgage, the whole shebang.”

“You’ve actually put in for a transfer?”

“The Met. Keep it between us for now. There’s no future here, Sean. Bright young lad like yourself should consider it too. How tall are you?”

“Five ten.”

“You’d be fine. I think.”

“What if I stood on tip toes.”

“What’s keeping you here, Sean?” he asked, ignoring my facetiousness.

“I wanna stay and be part of the solution.”

“Jesus. They must be putting something in the water or planting subliminal messages in those health and safety films.”

I laughed and we were about to turn into the McAlpines’ farm when a man with a shotgun came hurrying towards us.

I put the Beemer in neutral and wound the window down.

Tony put his hand on his service revolver.

“Oi, youse! This is a private road,” the man yelled.

“Put the gun down!” I yelled at him.

“I will not!” he yelled back.

“We’re police! Break open that gun this instant!” I howled at the fucker.

He hesitated for a moment, but didn’t break open the shotgun and kept coming towards us at a jog. He was in green Wellington boots, khaki trousers, a white shirt, tweed shooting jacket and a flat cap. He was dressed in a previous generation’s get up but he was only about forty if he was a day.

We got out of the Beemer, drew our weapons and put the car between him and us.

“First time I’ve drawn my gun in two years,” Tony said.

“A man shot at me with a shotgun just the other week,” I said.

“I’ve been on the job eight years and I’ve never had anyone shoot at me.”

“I’ve been shot at half a dozen times.”

“What does that tell you about yourself?”

“What does it tell you?”

“It tells me that people don’t like you. You rub them the wrong way.”

“Thanks, mate.”

The man jogged along the track towards us. He had a couple of beagles with him. Beagles I noted, not border collies, so he wasn’t a farmer, or at least he wasn’t farming today. He arrived at the Beemer slightly out of breath but not in too bad nick considering his little run down the hill. He had a grey thatch, a long angular face and ruddy cheeks. His eyes were blue and squinty as if he spent all his down-time reading and rereading Country Life.

“This is private property and you are trespassing,” he said.

“We’re the police,” I said again.

“So you claim,” he said, and then after a brief pause he added, “and even if you are, you’ll still need a warrant to come onto my land.”

His accent was a little peculiar. Not Islandmagee, not local. It sounded 1930s Anglo-Irish. He’d clearly been educated at an expensive private school, one where they learned you to say “leand” instead of “land”.

“We’re here to see the widow McAlpine,” I said.

“She’s a tenant on my property and this is a private residence. I would prefer it if you would come back stating the precise nature of your business on a warrant.”

I ignored him and turned to Tony. “This is the influence of American TV. Second time this week I’ve been told to get a warrant by some joker. Not like this in the old days.”

Tony cleared his throat. “Listen, mate, you don’t want to mess with us. We’re conducting inquiries into a murder investigation. We can go wherever the hell we like.”

The geezer shook his head. “No, you cannot. It was my younger brother who was murdered and I have seen the efficacy or lack thereof in your procedures. The RUC have not impressed me with their competence these last months.”

“You’re Dougherty’s brother?” I asked.

“Who’s Dougherty? I am speaking of Martin McAlpine, Captain Martin McAlpine. My brother.”

“No, sir, we’re not investigating that murder. Not as such. We’re looking into the death of Detective Inspector Dougherty who was murdered last night in Larne. We wanted to ask Mrs McAlpine a few questions.”

“What on earth for?” the man asked.

“We’d like to speak to her about it, sir,” I insisted.

“I’ll not have Emma disturbed. She’s already had several visits from so-called detectives coming out to see her this week on various wild goose chases. I suppose her name popped up on one of your computers – well, let me tell you something, young man, I am not going to stand for it. She’s been very upset by all this. She’s a strong woman but this nonsense has taken a toll. You fellows are messing with people’s lives.”

“Sir, it’s our duty to investigate Inspector Dougherty’s murder and we know for a fact that he came here recently to see Mrs McAlpine. We need to find out what they were talking about and so we will be questioning Mrs McAlpine and there is nothing, sir, that you can do about it,” I said with authority.

His cheeks reddened and he made a little grunting sound like a sow rooting for truffles. He rummaged in one of the pockets of his shooting jacket and removed a notebook and pencil.

“And what is your name, officer?” he asked me.

“Detective Inspector Sean Duffy, Carrickfergus RUC.”

“And yours?” he asked Tony.

“Detective Chief Inspector Antony McIlroy, Special Branch.”

“Good,” he said, writing the names in his book. “You will both be hearing from my solicitors.”

“I’ll look forward to that,” Tony said, and then went on: “May we inquire as to your name, sir?”

“I am Sir Harry McAlpine,” he announced, as if that was supposed to make us fall to our knees or genuflect or something.

“Fine, now if you’ll kindly move to one side, we’ll be about our business,” Tony said.

He moved. We got back in the BMW.

“Watch your dogs,” I said, and turned the key in the ignition.

“Funny old git,” Tony said.

“I’ll tell you something funny,” I began.

“What?”

“He lets two armed men go to his sister-in-law’s house only a couple of months after her husband, his brother, has been shot by a couple of armed men on a motorbike.”

“We told him we were police,” Tony protested.

“Aye, we told him, but he didn’t actually ask to see our warrant cards and he wasn’t surprised to see us, was he?”

“Which means?”

“He knew we were the police and he knew we were coming.”

“Because of Dougherty?”

“Because of Dougherty.”

“Why fuck with us, then?”

“He wanted to introduce himself, he wanted us to know that Emma McAlpine was the sister-in-law of Sir Harry McAlpine.”

“What good does that do?”

“He wanted to put the fear of God up us.”

“It didn’t work because neither of us have bloody heard of him.”

“I have an ominous feeling that we’re going to though, eh?”

Tony nodded and we drove into the familiar McAlpine farmyard.

Cora was chained up under an overhang, but soon began barking and snapping at us.

“Friendly dog,” Tony said.

“She does that, when she’s not tearing your throat out or watching calmly while two terrorists shoot her master.”

We got out of the car and walked across the muddy farmyard.

The hens were out, pecking at crumbs, and a proprietary rooster gave us the evil eye from a fence post.

There was a note on the front door:

“Gone to get salt. Back soon.”

I took it off and showed it to Tony, who was a little nearsighted.

“You think she means that literally?” Tony asked.

“What else could she mean?”

“I don’t know. Could be a country euphemism for something.”

Tony looked at his watch. This had been fun and all. But he was a man in a hurry and he had things to do. It didn’t matter about my time but his was valuable.

“I suppose we’ll wait for her,” I said.

“Aye,” Tony answered dubiously.

“Speaking of notes … Uhm, in your long and storied career has anyone ever sent you an anonymous note about a case?”

“All the time, mate. Happens all the time. In fact, I’d say that I get more anonymous tips than ones from people who actually come forward to be identified. Why, what did you get? You look worried.”

“Some character left me a note that was a verse from the Bible.”

Tony laughed. “Ach, shite, is that all? You should see the bollocks we get in Special Branch. Bible verses, tips about who may or not be a Soviet agent or the Antichrist … you name it, Sean. Last week we had a boy who got passed up to us from Cliftonville RUC, who had convinced them that he was ‘the real Yorkshire Ripper’. The cops in Cliftonville actually thought we might want to interview him.”

“‘Now I see through a glass darkly’ was the verse.”

“I remember that one. That’s popular with the nuts. Is that from the Book of Revelation?”

“Corinthians. It was a woman who left me the note. English accent maybe. She left me a note at Victoria Cemetery and then she went off on a motorbike.”

Tony pulled out his smokes and offered me one. We went over to the stone wall and sat down on it. Two fields over a horse was tied up against a tumbledown shed. Three fields the other way there was chimney smoke coming from the big house at the top of a hill – almost certainly the home of the lord of the manor. The rain, thank God, had taken a momentary breather in its relentless guerrilla war against Ireland.

“Go on,” Tony said.

“I called it in and they found the girl and arrested her and took her to Whitehead RUC. She spent a few hours in the cells and then she was supposedly taken away by a couple of goons from Special Branch. One of them was a guy called McClue – a fake name if ever I heard it – and of course when I called up Special Branch there was no McClue and no one had been sent to get her in Whitehead.”

Tony frowned. “Several things occur to me. First, if you had found her, what would you have charged her with? Leaving you a strange message and riding away on her motorbike? What crime is that? You’d be looking at a bloody lawsuit, mate. Secondly, who is she? Certainly not a lone nut if she had a couple of friends who were willing to pose as Special Branch agents to come get her.”

“So, not a nutter.”

“Or maybe she could be a very persuasive nutter. It’s the sort of thing a student would do, or a bored paramilitary or …”

“Or what?”

“You know what. A ghost. A fucking spook. Northern Ireland is thick with them.”

“MI5?”

“MI5, Army Intel, MI6. Or, like I say, a nutter, a student, one of your no doubt many dissatisfied lovers, a bored paramilitary playing you for a sap or a very bored spook also playing you for a sap.”

Tony’s pager went. He picked it up and examined the red flashing light.

“They’re looking for me. You think I could break into the widow McAlpine’s house and use her phone?”

“What would Sir Harry think? He’s probably watching us through a set of field glasses.”

“I doubt that. I’ll bet he’s furiously writing a letter to the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland who, no doubt, is a second cousin twice removed.”

I nodded and blew a double smoke ring. Tony’s pager went again.

“Fucksake!” Tony said. “I should never have left the bloody crime scene. The fuck was I thinking?”

“Tony mate, go back in the BMW, tell them you were following a lead and send some reservist back here with the car. I’ll wait until the widow McAlpine shows up.”

“I can take your wheels?” Tony asked.

“Sure.”

“I wouldn’t normally, but I am lead and maybe we shouldn’t be buggering off round the countryside like Bob Hope and Bing Crosby.”

“Hope and Crosby? Christ, Tony, you need new material, mate. Have you heard about this rock and roll phenomenon that’s sweeping the land?”

“You’re sure I can take the car?”

“Aye!”

“You’re a star. And you’ll be okay?”

“I’ll be fine.”

The deal was done. Tony pumped my hand and got in the Beemer.

He wound the window down. “Stay away from trouble,” he said.

“You should warn trouble to stay away from me.”

“Young widows in lonely farmhouses …” he said with a sigh, revved the Beemer and forced the clutch into an ugly second gear start.

16: SALT

I was glad that he was gone. I wanted to talk to Mrs McAlpine alone and to follow up with Sir Harry alone. Tony was too much of an equal. It required weight to deal with him and I needed the emotional space to think.

I walked to the farmhouse again and tried the door.

She’d locked it.

What country person locks their door?

“Maybe one who’s just had her husband gunned down by strangers,” I said to myself.

Cora barked at me.

The rooster gave me the eye.

I looked at the horse tied up across the fields and I looked at the track up to the manor.

The latter was less muddy than the former.

“The big house first, I think,” I said.

The slope was on a one in seven gradient that was a little taxing and I had to catch my breath at the top of it when I reached the stone wall around the house and the estate. There was an old lodge that had been boarded up but no actual gate itself.

There were assorted farm buildings along the wall and a short drive to the house lined with palm trees. Coconut palms, by the look of them, always an odd sight in Ireland but not uncommon: sailors had been bringing them back in pots for centuries.

A brisk walk underneath them brought me to the house. There were two cars parked outside: an Irish racing green Bentley S2 Continental and a black Rolls-Royce Silver Cloud. Both vehicles were about twenty years old and had certainly not been designed for country living. They were the worse for wear, particularly the Bentley, which was rusted almost to scrap. I wondered if the engine still turned over, but if it did the best you could have done with it was drive it to the junk yard. The Roller was in better nick but not much: the rear suspension was gone, the fenders were dinged and the original paint job had been touched up with what looked like house paint. Both vehicles were caked with mud and bird shit. I loved cars and this was a crying shame.

I gave the house a butcher’s: mid-century Georgian, red sandstone, three floors, a steep slate roof and a large wooden door that once had been painted a garish bright blue but which now had faded into a pleasing mottled indigo. The original, elegantly high, curved windows had been replaced by squat square jobs in brown frames. A black, sinister ivy was growing over two thirds of the house and all the third-floor windows were a suffocated tenebrous jungle. At least the ivy helped conceal the house’s shambolic condition, but if you looked closely you could see the unrepaired cracks in the walls, the missing tiles in the roof and the strange lean of the entire structure a good ten degrees off the verticle.

I was vibing a classic case of the aristo fallen on hard times: big empty rooms, mad woman in the attic, eldest daughter marrying some garish Yank with money.

I crunched on the gravel and walked up moss-covered granite steps to the porch.

I rang an ancient-looking push bell and contemplated a sour-looking cat who was sleeping on a heap of old newspapers. At least, I assumed he was sleeping, as he didn’t seem to breathe once.

A middle-aged woman came to the door. She was wearing an apron and looked annoyed. “He’s not in, so he’s not,” she said in a pissed-off West Belfast accent.

“Where is he?”

“Out with the dogs, so he is.”

I showed her my warrant card.

“Poliss, is it? Is there anything wrong? Will I get Betty?”

“Who’s Betty?”

“The housekeeper, Mrs Patton.”

“And who are you?”

“Cook. Aileen.”

“Who is else is in the house?”

“No one else. Ned will be with the horses.”

“Is that everyone?”

“Yes.”

I wrote the names in my notebook.

“Is there a wife, girlfriend?”

“No.”

“Can I come in?” I asked.

“I suppose so,” Aileen said.

I followed into her a rather gloomy looking hall with dark wood panelling and a staircase curving to the upper floors. There were hunting trophies on the wall, something I had not seen before anywhere in Ireland. Huge stags but also lions, leopards, a cheetah – all from another age.

The place was dusty and it smelled of mildew. The smell was so bad, in fact, that I gagged, and to cover my embarrassment I pointed at the beheaded animals.

“Do they not give you the willies, love? All them eyes looking down at you,” I said in the demotic.

She laughed. “Aye, they’re desperate so they are.”

“Is it from himself?” I asked.

I could tell now that Aileen was a Catholic. It was hard to say how I could tell but I could. Accent, body language, who knew? Sir Harry wasn’t a raging bigot then.

“No, no. From his da or his grand da more than likely,” she said.

“What does he do for fun?”

“When he’s not in his office in Belfast he just likes the quiet time. Potters around the garden, reads in his library.”

“Terrible about his brother, the captain in the army.”

“Shocking, so it was. Shocking.”

“I suppose you didn’t hear the killing from here?”

“Oh, no. It’s too far away. We didn’t hear anything.”

“And there were no witnesses?”

“From up here? No.”

“Was Sir Harry at home that day?”

“He was out in the garden, I think. He went over straight away. Of course there was nothing he could do.”

“No. Martin was his younger brother?”

“Yes. Eight or nine years between them, I think.”

I shook my head. “Must have been awful that morning.”

“Oh yes, I’ll never forget that day. Shocking, so it was. Such a cowardly act. They’re vermin. Vermin shooting a man in the back.”

“He was shot in chest,”

Her eyes scolded me. “What does it matter! What does that matter? What are you here for, anyway? I told you Sir Harry was out. Wait here.”

Before I could call her back she vanished through a door and a rather different woman appeared in blue suit, white pearls and a black bouffant. She was about forty, thin, thin-lipped, and there was a touch of old Hollywood in her heavy lidded eyes and defiant unfeminine chin.

She walked towards me, all systems bristling. “May I see your identification?” she asked.

I showed her the warrant card.

“I take it that you’re Mrs Patton?” I asked.

She nodded. She was from Derry, by the sound of it. Brisk and business-like. I dug the whole Rebecca scene, but if she was Mrs Danvers and Sir Harry was Max de Winter, what did that make me – Joan fucking Fontaine?

I took out my fags.

“Oh, there’s no smoking in here,” Mrs Patton said.

I put the cigarettes back in my pocket with a mumbled “Excuse me”.

A little victory for the home team, there.

“And how can we be of service today?” she asked.

“I need to see Sir Harry. I was wondering if I could, uh, if I could wait for him in your lovely garden,” I said, putting on a bit of my Glens accent.

“The garden? Why?” she said, both disarmed and suspicious.

“I’m a bit of flower nut and I thought I could spend some time there until Sir Harry comes back. I’ve heard wonders about his garden.”

“You wish to wait for Sir Harry in his garden?”

“If it doesn’t put anyone out.”

“No … I, uh, I don’t expect that it would.”

She looked at me and nodded curtly. “Follow me,” she said.

We went through a spotless kitchen, all gleaming surfaces and pots on hooks. The appliances had all been brand new in about 1975. Sir Harry didn’t seem like the sort of man who would let his cars rot but get expensive kitchen gear. It must be a feminine influence. His wife had bought that kit, a wife who was, now, where exactly?

I walked through the back door and out into the kitchen garden.

“Here you go,” she said.

I pretended to be fascinated by an ugly yellow smudge of daffodils – the only thing at all growing back here.

Of course I had already seen the greenhouse through the kitchen window.

Mrs Patton said “I’ll leave you to it,” and disappeared back inside. I lit a cigarette. I knew that she’d be spying on me but there was a hedge blocking the rear entrance to the greenhouse from the back windows of the residence. I finished my smoke, inspected more of the flowers and walked behind the hedge. I waited a moment for a cry or footsteps hurrying towards me but I heard nothing. I turned a rusted iron handle and went inside the greenhouse. I didn’t know what I was expecting to find but I was not counting on a completely empty space. No plants, no pots, nothing. I wrote “a clean concrete floor, a few gardening tools”, in my notebook. The gardening tools were one rake and one hoe.

I had got what I came for on this trip.

I wrote “Down at heel scion. Hiding something or just an arse? No rosary pea or anything else in the greenhouse” in my notebook and walked into the house again.

Mrs Patton intercepted me in the gloomy hall.

“Inspector Duffy, is anything amiss?” she asked.

“No, nothing’s amiss, Mrs Patton. However, I’ve just remembered that I have to be somewhere else. I was so taken with your daffodils that I completely forgot. You’ll have to excuse me, ma’am. Thank you for your hospitality.”

“Oh … oh, what shall I tell Sir Harry?”

“No message, thank you,” I said.

I walked briskly out of the hall and onto the crunchy gravel drive. I gave the Bentley and the Roller a sympathetic look and I juked under the palm trees.

Thunder rumbled in a grey skin and it began to rain with big heavy, sporadic drops. At the hill’s summit I surveyed the broad wet valley filled with cows and sheep and fields too boggy to accommodate man or beast.

The prospect to the north was of Larne Lough and Magheramorne on the far shore.

The widow McAlpine’s farm was a good mile off on the far side of a hill. You wouldn’t be able to see it even from the third floor of this house. No one inside could possibly have witnessed Martin’s murder. There would be no teenage maids too frightened to testify but who could be broken by the age-old tactics of question after question after question.

I dandered down the hill and in twenty minutes I was back at the farm.

I went round the back of the house and tried the rear door.

It too was locked. Cora was barking herself hoarse now. A side window was open, but it was too small for me to squeeze through. I lit my last ciggy, climbed a style over the stone wall and strode out across the fields in the direction of the tied-up horse.

The pasture was little better than a bog with some tuft grass and sodden heather, and in a few moments my DMs were soaked through. Sheep pellets were everywhere and in a slurry pond there was the carcass of an old ewe, suspended just beneath the surface.

The horse was an old white mare who barely registered my presence as I approached. I stroked her head, but I had no sugar to offer her. I grabbed some moist dandelion leaves and held them under her nose but she turned her head away disdainfully. “Spoiled rotten, so you are,” I said, and gave her a pat on the neck.

I was curious about the shed so I knocked on the door, but there was no answer. I opened it and saw a lantern hanging from the ceiling and a ladder leading underground.

“What’s all this?” I muttered, but the mare kept her thoughts to herself.

I looked down into the hole. It was a vertical tunnel lit by a series of incandescent bulbs. The walls were white, chalky and crumbly and I wasn’t encouraged that the rickety metal ladder was bolted to them. There was a slightly unpleasant, sulphurous smell which also boded ill.