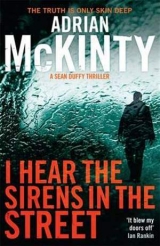

Текст книги "I Hear the Sirens in the Street"

Автор книги: Adrian McKinty

Жанры:

Триллеры

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 7 (всего у книги 19 страниц)

11: NO PROGRESS

A wet April morning in a small provincial city on the fringe of Europe. A bunch of cops carrying out one of the most basic of all cop activities: executing a search warrant. And although everywhere the serving of search warrants is a protocol driven, largely crepuscular activity, nowhere in the “civilised” world does the task come with so much palaver as in Northern Ireland.

Three grey armoured Land Rovers driving up a dreary motorway towards Dunmurry, a drab, soulless sink estate in West Belfast, recently saved from perfect entropy by the DeLorean Motor Company which had been established here precisely for the purpose of resurrection.

Elsewhere on Eurasia in this spring of 1982 men are working in factories, making consumer goods and cars, harvesting winter wheat and barley, toiling in terraced rice paddies; from Shanghai to Swansea there is order, work and discipline and only here, at the edge of the continent, is there war. Funny that.

Getting the warrant has been easy and the Chief has wielded his magic with the local brass. He gathers Crabbie, Matty and myself in his pungent office to share the news. “We have our warrant and we have an okay from the RUC and Army chiefs. This is how the system works, lads. You just gotta be nice and humble to the higher ups,” he says, presenting the wisdom of the ages as some kind of hard-won insider scoop.

Chief Inspector Brennan, Sergeant Burke and Inspector McCallister are in one Land Rover. In a second there are half a dozen police reservists dressed up in riot gear. In a third Matty, Crabbie and myself.

As we drive through the seething estates the locals make us welcome by throwing milk bottles filled with urine from tower blocks and the flat roofs of houses. Of course, if it was night time or an occasion of particular tension, burning vodka bottles filled with petrol would be arcing in our direction.

The convoy pulls up outside a bed and breakfast which lies at the end of a terrace. Reserve constables fan out of the second Land Rover to guard the perimeter. We get out of ours. I am not wearing full riot gear but a simple blue suit and a black raincoat.

Matty is unimpressed by the Dunmurry Country Inn, which looks like a bit of a shitehole. “What was O’Rourke staying here for?” he asks.

An excellent question, that will, no doubt, be asked many times before this investigation is over.

“This way, lads,” Chief Inspector Brennan announces, and we follow him down the path. Sergeant Burke is with him for protection. Sergeant McCallister is waiting back in the Rover with his machine gun at the ready.

We knock on the door.

We are expected.

The door opens. A man called Willy McFarlane opens it and stands there large as life and twice as ugly. He’s five eight, lean, with a handlebar moustache, a black comb-over, aviator sunglasses. He’s wearing a loud blue polyester sports jacket over a yellow Six Million Dollar Man T-shirt. Knife scars. Jail house ink. I dig the T-shirt.

“Are you gentlemen looking for a place to stay?” he says, with a chuckle.

“We’re looking for Richard Coulter,” I tell him.

“Mr Coulter is at a charity lunch in London. Princess Diana is going to be there,” Willy McFarlane says.

“Is this his place of business?” I ask.

“One of many.”

“Who are you?”

He tells us who he is.

“We have a warrant to search these premises, Mr McFarlane,” Brennan announces.

“Be my guest,” McFarlane says with another wee laugh.

“Work your way through from top to bottom and back again. I’ll question Mr McFarlane here.”

The bed and breakfast is small. Two terraced houses knocked into one. Four guest rooms. O’Rourke had been staying in room #4 and I know McCrabban will pay special attention there but I ask him to check all the bedrooms to look for any possible evidence. I’m letting Crabbie lead the search while I run the wheel on McFarlane.

“Upstairs, downstairs. Meet me in the back kitchen,” I tell him.

The back kitchen.

The smell of lard and Ajax. Flypaper hanging against the wall. Clothes drying on an internal clothes line. A checkered linoleum floor: the kind that blood cleans up easily from. Mrs McFarlane, a small birdlike woman, is making tea, humming to herself contentedly.

She’s not a stranger to unusual guests or peelers with machine guns.

McFarlane’s smoking Bensons. Relaxed.

Let’s unrelax the fucker.

“You know why we’re here?”

“No,” McFarlane says, unconcerned.

“Mr Coulter’s account charged seven hundred pounds on one of your guest’s American Express Cards last November. A Mr Bill O’Rourke from Boston, Massachusetts,” I say.

“What about it?”

“Your room rates are twenty pounds a night and he checked out after two nights. It doesn’t compute, does it?”

William McFarlane is not fazed. He rubs a greasy fist under his chin. “I charged that bill. Mr Coulter has nothing to do with it and I’ll thank you not to mention his name again.”

“You charged the bill? So you admit it?”

“Aye. I remember yon boy. He wanted Irish Punts. He wanted six hundred quid’s worth of Irish Punts. I got them for him, legally I might add, from the Ulster Bank in Belfast. In fact I think I might have the receipt right here.”

He produces a piece of paper from his trouser pocket.

What a joke. What a frigging laugh riot. He knew we were coming and why we were coming. Someone tipped off his boss and his boss tipped him.

I take the receipt and read it.

It’s exactly what he says it is. A receipt for six hundred and fifty Irish pounds from the Ulster Bank on Donegall Square, Belfast. Transaction dated 25 November 1981.

I bag it and put it in my jacket pocket.

“What did he want the money for?” I ask.

“He didn’t say.”

“He just stayed here two days and left?”

“That’s right.”

“Did he say where he was going?”

“No.”

“He paid his bill in full?”

“Aye. No problems.”

“How many other guests did you have?”

“At that time?”

“Yes.”

“None.”

“You’re a bit out of the way here, aren’t you? A bit off the tourist trail.”

“Aye, I suppose so.”

“How many guests do you get a month, would you say?”

“Well, it depends.”

“On average?”

“I don’t know. A dozen. Maybe more, maybe less.”

Hmmmm.

Mrs McFarlane brings me a mug of tea, a Kit Kat and a publication called Teetotal Monthly whose headline for April is “Hibernia Despoiled By Demon Gin”. I thank her.

“Eat that up, love, you’re skin and bones and you look hungry enough to eat the beard of Moses,” she says.

I drink the tea and light a cigarette. McFarlane and I look at one another and say nothing. I read Mrs McFarlane’s pamphlet. There’s a nice exegesis of the wedding feast at Cana which explains that Jesus Christ turned the water not into wine but into a form of non-alcoholic grape juice.

McCrabban comes back downstairs.

He shakes his head.

Brennan and Sergeant Burke appear from wherever they’ve been. Mrs McFarlane offers to make them tea. Brennan accepts. Sergeant Burke goes outside to have a smoke.

I let McCrabban ask McFarlane all the questions I have already attempted in order to ascertain if there are any inconsistencies.

There are none.

We drink our teas and assume that Edwardian Belfast fake politeness that coats this city like poison gas. Matty finally comes down with his fingerprint books and forensic samples.

“Are you all done, mate?”

“Aye,” he says. He’s got something in his hand. He shows it to me. It’s from the pantry. A Chicken Tikka Pot Noodle.

“Well done,” I tell him.

Perhaps a flash of concern flits across McFarlane’s eyes.

I go up to bedroom #4 and ask Crabbie to follow.

Chintz wallpaper on the staircase, thin orange carpet, pictures of Belfast that look as if they are framed postcards. There’s a smell too: vinegary and sour.

I pause on the top step.

“What was O’Rourke staying in a place like this for?”

Crabbie shrugs. “He was only here for two nights.”

“Why here? Why Dunmurry? No one visits Dunmurry.”

“Some people must do so otherwise there wouldn’t be a bed and breakfast,” Crabbie says.

“Wise up, mate, this place is clearly a money-laundering scheme.”

We go along the landing to room #4.

Typical Belfast terraced bedroom: small, damp, depressing, with an old fashioned bed covered in many layers of itchy woollen blankets. Also: a grainy window that does not open; a huge Duchess chest of drawers with a large fixed mirror; an elm desk and a plastic chair next to the window; fleur de lys wallpaper from a bygone age; sepia prints on the wall of 1920s Ireland. And that smell: mildew, vinegar, cheap cleaning products. I look under the bed and examine the Duchess chest of drawers which is a monstrosity of a thing, the wood dyed to look like mahogany, but really pine. The drawers are empty and the mirror could do with a good wipe down.

I examine the desk but there’s nothing there and again we look at the chest of drawers. There are strange wear marks on the carpet, an ugly case of rising damp on two of the walls.

“We found nothing, either,” Crabbie says.

“McFarlane says he wanted Irish currency. That’s why there was such a big bill,” I tell Crabbie.

“So he went down to the Republic?”

“Could be.”

“Maybe he was murdered down there?”

“How did the body end up here?”

“A million ways. They dump the suitcase in a truck or a bin lorry going north?”

I shake my head. “We’re not getting off that easy. The suitcase came from here and the body was found here. This is our problem.”

We take a last look around.

“What do you think those marks are on the carpet?” I ask Crabbie.

He shrugs. “Is that where people kick the chair over when they hang themselves from the light fitting?”

We go back downstairs.

Brennan looks at me. “Well?”

“Well what?”

“When do we depart this royal throne of shit, this cursèd plot?”

“We’ll go when I think we’re done,” I say.

“Some of these men are on overtime, Duffy.”

“I didn’t ask you to bring them, sir.”

“It’s a tough manor.”

“Everywhere’s a tough manor.”

Brennan pulls a pipe out of his raincoat pocket and begins to fill it.

“How long, Duffy?” he insists.

“Give me five more minutes. Let’s see if the bugger’s got a greenhouse at least … Matty, come with me!”

We push through the kitchen into the wash-house where more clothes are hanging out to dry and coal is piled high in coal buckets and an old bath.

Sergeant Burke is leaning against a wall, vomiting.

“Are you okay, mate?” I ask him.

“Have you got any hair of the dog, Duffy?” he asks.

I look at Matty, who shakes his head.

“Go get the hip flask from Inspector McCallister,” I tell Matty. “Tell him it’s for me.”

He nods and goes back inside.

“Are you okay?” I ask Burke.

“I’m all right. I’m all right. Collar’s too tight or something.”

“Shall I get a medic?”

“I’m fine!” he says.

Matty comes back with McCallister’s brandy. Burke grabs it and swallows half of it. He wipes his mouth and nods.

“Knew that would sort me,” he says, with a unpleasant smile.

He goes back inside on unsteady legs.

When he’s gone I whisper to Matty: “You and me a few years from now, if we don’t watch out.”

“I’ve got fishing, what have you got, mate?” Matty asks.

“Uh …”

“You should get a pet. A tortoise is good. They’re lots of fun. You can paint stuff on their shells. My sister’s looking to get rid of hers. Twenty quid. It’s got a great personality.”

“A tortoise isn’t my idea of—”

“Hey, boy! Does your warrant cover the back garden?” McFarlane yells at Matty from the kitchen window.

“Show him the warrant, will you, DC McBride? And tell him that if he calls you boy again you’ll lift him and bring the fucker in for a comprehensive cavity search.”

Matty shows McFarlane the legalese and yells back to me: “Inspector Duffy, it sounds like somebody’s not keen for us to investigate his back yard.”

“Aye, I wonder what we’ll find,” I say.

What we find is a back garden which is a dumping ground for assorted garbage: old beds, old tyres, mattresses. In many places thin reed trees and ferns are growing through a thicket of grass. Along the wall there seems to be an ancient motorbike; but more importantly, there in the north-west corner, there’s a greenhouse.

We open the door and go inside. It’s clean, humid, well-maintained and all the windows are intact. There are a dozen boxes of healthy tomato plants growing in pots along the south-facing glass.

“Tomatoes,” Matty says.

Matty puts on his latex gloves and begins digging through them to see if there’s anything else growing in there, but in pot after pot he comes up only with soil.

“Nowt,” Matty says.

“Look through those bags of fertilizer.”

Nothing in there either. We stand there looking at the rain running down the thirty-degree angled roof in complicated rivulets.

He looks at me.

“You’re feeling it, too?” I ask him.

“What?”

“A feeling that we’re missing something?”

“No.”

“What were you looking at me like that for?”

“I just noticed all those grey hairs above your ears.”

“You’re an eejit.” I examine the plants, but Matty’s right: these really are genuine tomato plants and there is nothing secreted in the pots.

McFarlane gurns at us through the glass before going back towards the house.

“He’s lying about something, Matty, but what?”

“I don’t know. Maybe he’s Lord Lucan. Maybe he shot someone once from a grassy knoll. Do we head now? The Chief’s getting shirty,” Matty asks.

I walk outside the greenhouse and do a thorough three-sixty perimeter scan – and low and behold, between the greenhouse and the wall I spot a plant pot sitting on a compost heap: red plastic, hastily thrown away. There’s no plant in it now but clearly there once was and perhaps residue remains.

“What do we have here?”

“What is it?”

“Gimme a bag, quick,” I tell him.

We put the plant pot in a large Ziploc to protect it from the rain.

We march back into the house.

“What have you got?” the Chief asks.

“Evidence, boss!” Matty says with an unconcealed note of triumph.

I look at McFarlane.

His face is blank.

The complaining, however, has dried up, which can only be a good sign.

I thank Mrs McFarlane for the tea and her hospitality.

We file outside.

A crowd.

A rent-a-mob. Three dozen youths in denim jackets.

The reserve constables looking nervous.

“SS RUC!” a kid yells and the chant is half-heartedly taken up by the others. Someone from the back throws a stone.

“Time to head, gentlemen, these fenian scum will make it hairy in a minute or two,” Brennan says.

These fenian scum.

The word throws me. Gives me a strange out-of-body dissonance for the second time today. How did it happen that I’m on the side of the Castle, on the side of the Brits? One of the oppressors, not the oppressed …

“Come on lads, let’s go!” Chief Inspector Brennan says.

We get back into the vehicles as a hail of bricks, bottles and stones came raining down on the Land Rover’s steel roof.

We make straight for the M2 motorway, the shore road, Carrickfergus Police Station.

“What now, boss?” Matty asks.

“Take a Land Rover and a driver and get this plant pot up to the lab. I want it examined by the best forensic boys on the force and I want you to stay with those fuckers until the job is done. If they find any rosary pea material in here at all it’ll be enough to hang McFarlane.”

Matty takes the plant pot and streaks off like Billy Whizz.

The rest of us head home.

#113 Coronation Road.

I put on “For Your Pleasure” by Roxy Music.

I fry some bacon and onions.

I eat my dinner and listen to both sides of the LP which I haven’t played in seven or eight years.

When it’s over I put on my raincoat walk back down to the station to wait for Matty. He shows up at nine.

“Good news?”

He shakes his head. “The only organic material in that pot was a withered tomato plant.”

“Are you sure?”

“The lads were 100 per cent sure. A dead tomato plant. Nothing else.”

“No rosary pea or indeed anything weird?”

“No.”

“Shit.”

“Sorry, boss.”

“Thanks, Matty.”

No rosary pea. No Abrin.

“Do you want to go next door to the pub?” I ask him.

“Is that an order?”

“No.”

“Well, in that case I’d rather not, if you don’t mind.”

“All right, I’ll catch you another time. I’ll go myself.”

I juke next door and order a pint of Guinness and a double Scotch. A redhead called Kerry asks me if I will buy her a drink. She drinks a blackcurrant snakebite, which apparently is equal parts lager and cider with a dash of blackcurrant in a pint glass. After two she’s toast. I tell her the joke about the monkey and the pianist in the bar. She thinks it’s hilarious. She asks what I do for a living and I let slip that I’m a copper … And that, my friend, is it. She’s either Catholic or has your bog standard hatred of the police. When I come back from the toilet she’s gone. She’s been through my wallet, but she’s only taken a twenty-pound note to get a taxi, which, when you think about it, isn’t so bad.

I order a double Bush for the road, hit it and walk back through the rain.

My head’s splitting. I stop to urinate outside the Presbyterian Church and an old lady walking her mutt tells me that I’m a sorry excuse for a human being. “I agree with you, love,” I say but when I turn round to make the argument there’s no one there at all.

12: A MESSAGE

A week went by without any developments. Like the majority of murder cases in Northern Ireland this one was starting to die. No new information from America. No eyewitness testimony. No calls on the Confidential Telephone. Mr O’Rourke had last been seen in Dunmurry. He’d got some Irish money, checked out of his crummy B&B and then he’d turned up dead. In another week or so the Chief would tell me to put the O’Rourke case on the back burner. A week after that, we’d move it to the yellow folders: open but not actively pursuing …

It was a Wednesday. The rain was hard and cold and coming at a forty-five-degree angle from the mountains. The sound of shotguns somewhere up country woke me at seven. I listened for a moment or two but there was no return fire and it was probably just a farmer going after foxes.

I put on the radio.

The local news was bad. An army base in Lurgan had been attacked with mortars, a firebomb had destroyed a bus depot in Armagh and an off-duty police reservist had been shot dead at the wheel of his tractor in Fermanagh.

The national news was about the Falklands War. Ships were still sailing south, the Pope wanted a peaceful resolution, the Americans were doing something, the EEC was calling for sanctions against Argentina.

I lay under the sheets for a while and finally wrapped myself in the duvet and dragged my ass downstairs.

I called my mother. She said she was just going off to play bridge. Dad was also on his way out, going birding up the Giant’s Causeway.

“What do you see up there?” I asked, faking interest.

“Buzzards, kestrels, peregrines, sparrowhawks, gannets, occasional black and common guillemots, razorbills, eider ducks, purple sandpipers, colonies of fulmar, kittiwakes, Manx shear-waters, puffins, twites.”

“You’re making half those up.”

“I am not.”

“There’s no such bird as a fulmar or a twite. I wasn’t born yesterday.”

“Fulmar from the Norse ‘full’, meaning foul, ‘mar’ meaning gull, ‘fulmar’, because of their oily bills. They’re a type of seagull. Highly pelagic birds …”

“Which means?”

“They spend most of their life out at sea, like albatrosses.”

“And a twite?”

“A small passerine bird in the finch family.”

We both knew that I didn’t know what a passerine bird was, but an explanation would weary me. “I have to go, Dad.”

“Okay, son, see you, take care of yourself.”

“I will.”

I hung up and put on Radio Albania to get a Maoist version of the world news. I put Veda bread in the toaster and made a Nescafé. I ate the toast at the kitchen table and thought about my folks. They’d never spoken about why they’d only ever had one kid. I hadn’t been deprived of love, but I’d just never really connected with either of them. Dad was into fishing, bird watching, hare coursing, fell walking, hiking, that kind of thing, and as a wean I’d thought that I was interested in it too, but I was only fooling myself. When I told them I was going to be a cop they neither approved or disapproved. If I’d told them I was going to be a terrorist I probably would have gotten the same reaction.

I carried the coffee into the living room.

I put on all three bars of the electric heater and stared out stupidly at the front garden. Radio Albania’s spin on the Falklands War was that it was a struggle between two fascist regimes in an attempt to repress revolt among their own working classes.

I trudged back into the kitchen, changed the channel to Radio Four to get confirmation that this really was a Wednesday. I had accumulated a lot of leave and in a deal with Dalziel in clerical I was taking two Wednesdays a month off until my leave was back down to manageable levels.

I made another cup of coffee and when I discovered that it was indeed a Wednesday I retired to the living room with a Toffee Crisp and my novel.

I was reading a book called Shoeless Joe which had gotten a good review in the Irish Times and was about a man obsessed by baseball and J.D. Salinger – but not in a creepy Mark David Chapman way.

The phone rang.

I trudged into the hall and picked it up.

“Hello?”

“Is this Duffy?”

“It is.”

“Can you be at the shelter in Victoria Cemetery in ten minutes?” a woman asked. A young woman, with an odd voice. English. Old fashioned. So old fashioned it sounded like she was doing an accent or something.

“Sorry?”

“Can you be at the Victoria Cemetery shelter in ten minutes?” she repeated.

“I can, but I’m not going to be.”

“I’ve got information about one of your cases.”

“Come down my office, love, anytime,” I said.

“I’d like to meet with you in person.”

“I don’t do graveyards. It’ll have to have to be at the office.”

“This will be worth your while, Duffy. It’s information about a case.”

“Listen, honey, they pay me the same wages whether I solve the cases or not.”

The lass, whoever she was, thought about that for a second or two and then hung up.

She didn’t call back.

I looked out the window at the starlings for ten seconds. One of the little bastards shat on my morning paper.

“Fuck it,” I muttered, ran upstairs, pulled on a pair of jeans and gutties. I threw a raincoat over my Thin Lizzy T-shirt and shoved my Smith and Wesson .38 service piece in the right hand coat pocket.

“I don’t like it,” I said to myself and sprinted out the front door.

The graveyard was on the other side of Coronation Road, over a little burn and across a slash of waste ground known as the Cricket Field – the de facto play area for every unsupervised wean in the estate.

The sky was black.

The wind and rain had picked up a little.

I jumped the stream and scrambled up the bank into the Cricket Field: burnt-out cars and a gang of feral boys throwing cans and bottles into a bonfire.

“Hey, mister, have ye got any fags?” one of the wee muckers asked.

“No!” I replied and hopped the graveyard wall.

I circled to where I could see the concrete shelter that had been built to give protection to the council gravediggers while they waited for funeral services to be concluded. This part of Carrick was on a high flat escarpment exposed to polar winds, Atlantic storms and Irish Sea gales. I’d been to half a dozen funerals here and it had been pissing down at every one of them.

I had envied the men in the shelter, although I had never actually been in it myself. It was large and could easily accommodate a dozen people. If I remembered correctly there were several wooden benches that ran along the wall. There were no doors to get into it as it was open to the elements on the south side like a bus shelter.

If I could circle due south through the petrified forest of graves I could easily see if someone was waiting in there or not.

I ran at a crouch through the Celtic crosses and granite headstones and the various family plots and monuments.

I made it to the perimeter wall on Victoria Road due south of the building. I looked across the cemetery and squinted to see into the shelter and moved a little closer and looked again.

No one was there.

I walked a few paces forward until I was behind a large monument to a family called Beggs who had all been killed in a house fire in the ’30s.

I watched the cemetery gates and the shelter.

No one came in, nobody left.

There appeared to be no one else here but me.

Rain was pouring down the back of my neck.

It was cold.

And yet I knew that the place was not deserted.

She was here, whoever she was.

She had called me from the phone box on Victoria Road and now she was here, waiting for me.

Why?

I put my hand in my pocket and clicked back the hammer on the revolver and stepped out from behind the Beggs family headstone.

I walked slowly to the graveyard shelter, scanning to the left and right and whirling one-eighty behind me. I raised my weapon and carried it two-handed in front of me.

She was here. She was watching. I could feel it.

I entered the shelter and turned round to look back at the graveyard.

Nothing moved but there were many hiding places behind the trees, the tombstones and the stone walls.

There was no glint from a pair of binoculars or a rifle scope.

“I came. Isn’t that what you wanted?” I said aloud.

A crow cawed.

A car drove past on Victoria Road.

I sat on a long bench that had been vandalised down to a couple of wooden slats.

I stared out at the dreary rows of headstones, Celtic crosses and monuments.

Nope. There was nothing and nobody.

She was more patient than me and that was not a good thing. Impatient coppers got themselves killed in this country.

Thunder rumbled over the lough.

The rain grew heavier. Rivers of water were gushing down the Antrim Plateau and forming little pools in the cemetery. I pulled out me Marlboros and lit a cigarette.

I walked to the edge of the shelter and looked out. Worms by the hundred were disgorging themselves from their human feast and writhing on the emerald grass.

Grass so green here that it hurt to look at it.

Why? Why had she called me? What was this about? Had I disrupted her plans by coming over the wall and not through the gates? Had she got cold feet? Was it just a regular crank call?

I sat there, waited, watched.

She waited too.

The sky darkened.

Magpies descended to feast on the snails and earthworms.

“Hello!” I yelled out into the weather. “Hello!”

Silence.

I turned and walked back and it was only then that I noticed the envelope duct-taped to the back of the bench.

I immediately looked away and lit another cigarette.

When the cigarette was done, I turned round with my back to the exposed south entrance. If she was watching she wouldn’t know what I was doing. Perhaps she would think that I was pissing against the wall.

I took out a pair of latex gloves from inside my raincoat pocket and put them on.

I checked for wires or booby traps and finding none ripped the envelope off. I examined it. It was a green greeting card envelope. Keeping my back facing south, I opened it. Inside there was a Hallmark greeting card with a shamrock on the cover.

I opened it. “Happy Saint Patrick’s Day” was the message printed inside.

At first I thought there was no message at all but then I saw it opposite the greeting.

“1CR1312”, she had written in capital letters in black pen on the top of the page.

You could, perhaps, have mistaken it for a serial number.

I noticed that actually there was a space between the 3 and the 1 so that really it read: “1CR 13 12.”

Even a non-Bible-reading Papist like me knew what it was.

It was a verse from the New Testament.

Paul’s first epistle to the Corinthians, chapter 13, verse 12.

And not only that – it was something familiar. Something I should know.

The answers would be in my King James Bible back home. My house was only two minutes away, but there was something I had to do here first.

I put the card back in the envelope and retaped it to the seat back.

I pretended to zip up my fly, then I turned round and lit another cigarette.

I did up the collar on my coat and walked out of the shelter towards the cemetery exit. I didn’t look to the left or right, instead I hurried on down Coronation Road and only when I was at Mrs Bridewell’s house did I stop and turn and look: two kids playing kerby, a woman pushing a pram, a stray dog sleeping in the middle of the street; no one else, no strangers, no unknown cars.

I ran up the path and knocked on Mrs Bridewell’s door.

She opened it almost immediately. She had curlers in and she was smoking a cigarette. She was wearing a pink bathrobe, pink fuzzy slippers and no make up. She seemed about twenty. She was really very good-looking.

“Oh, Mr Duffy, I thought it was the milk man come back to replace those bottles that the—”

“I’m sorry to bother you, Mrs Bridewell, but your front bedroom must have an unobstructed view of the graveyard – from mine the big chestnut tree at the cricket field is in the way.”

“We can see into the graveyard – what’s this all about?”

“Do you mind if I run up there? We’ve been getting reports about vandals spray-painting the shelter and stealing flowers from the graves and I think I just saw one of the little buggers go in there.”

“Of course. Of course. That’s shocking, so it is. I’ve complained about them weans to the police but nobody ever pays any mind.”

I ran upstairs to her bedroom. Her husband wasn’t here as he was still over in England looking for work. The bedroom smelled of lavender, there was a white chest of drawers, the bed sheets were peach, the wallpaper had flowers on it. A black lacy bra was sitting at the top of a laundry basket. It distracted me for a second, before the bra’s owner followed me into the room.

“Why didn’t you just wait for him in the cemetery?” she asked.

“It’s a she. And if she sees me in the graveyard she won’t do anything, will she? But if I can catch her in the act from up here, then Bob’s your uncle, I’ll have physical evidence and we can haul her up before the magistrate.”

“Won’t it just be your word against hers? You should have brought a camera,” Mrs Bridewell said, which was her way of letting me know that she was not going to be dragged into this. Like everyone else on Coronation Road, testifying against criminals – be they paramilitary mafia or mere teenage vandal – was not an option.