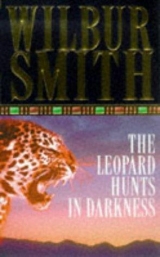

Текст книги "Leopard Hunts in Darkness"

Автор книги: Wilbur Smith

Соавторы: Wilbur Smith

Жанр:

Исторические приключения

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 12 (всего у книги 33 страниц)

in the middle of his chest, right over the heart.

Tungata dropped over backwards and lay still– Crai crawled to him and reached for his unprotected throat with both hands. He felt the ropes of muscle framing the sharp hard Jump of the thyroid cartilage and he drove his thumbs deeply into it, and, at the feet of ebbing life under his hands, his rage fell away he found he could not kill him.

He opened his hands and drew away, shaking and gasping.

He left Tungata lying crumpled on the rocky earth and crawled to where Sally-Anne lay. He picked her up and sat with her in his lap, cradling her head against his shoulder, desolated by the slack and lifeless feel of her body. With one hand he wiped away the trickle of blood before it reached her eyes.

Above them on the road the following truck pulled up with a metallic squeal of brakes and armed men came swarming down the slope, baying likea pack of hounds at the kill. In his arms I ikea child waking from sleep, Sally Anne stiffed and mumbled softly.

She was alive, still alive and he whispered to her, "My darling, oh my darling, I love you so!" our of Sally-Anne's ribs were cracked, her right ankle was badly sprained, and there was serious bruising and swelling on her neck from the blow she had received. However, the cut in her scalp was superficial and the X-rays showed no damage to the skull. Nevertheless, she was held for observation in the private ward that Peter Fungabera had secured for her in the overcrowded public hospital.

It was here that Abel Khori, the public prosecutor assigned to the Tungata Zebiwe case, visited her. Mr. Khori was a distinguished-looking Shana who had been called to the London bar and still affected the dress of Lincoln's Inn Fields, together with a penchant for learned, if irrelevant, Latin phrases.

"I am visiting you to clarify in my own mind certain points in the statement that you have already made to the police. For it would be highly improper of me to influence in any way the evidence that you will give," Khori explained.

He showed Craig and Sally-Arme the reports of spontaneous Matabele demonstrations for Tungata's release, which had been swiftly broken up by the police and units of the Third Brigade, and which the Shana editor of the Herald had relegated to the middle pages.

"We must always bear in mind that this man is ipso jure accused of a criminal act,. and he should not be allowed to become a tribal martyr. -You see the dangers. The sooner we can have the er*ire business settled mutatis mutandis, the better for everybody." Craig and Sally-Anne were at first astonished and then made uneasy at the despatch with which Tungata Zebiwe was to be brought to trial. Despite the fact that the rolls were filled for seven months ahead, his case was given a date in the Supreme Court ten days hence.

"We cannot nudis Verb keep a man of his stature in gaol for seven months," the prosecutor explaine "and to grant him bail and allow him liberty to inflame his followers would be suicidal folly." Apart from the trial, there were other lesser matters to occupy both Craig and Sally Anne Her Cessna was due for its thousand, hour check and 'certificate of airworthiness'. There were no facilities for this in Zimbabwe, and j they had to arrange for a fellow pilot to fly the machine down to Johannesburg for her. "I will feel likea bird with its wings clipped," she complained.

"I know the feeling," Craig grinned ruefully, and banged his crutch on the floor.

"Oh, I'm sorry, Craig."

"No, dorA be. Somehow I no longer mind talking about my missing pin. Not with you, anyway."

"When will it be back?"

"Morgan Oxford sent it out in the diplomatic bag and Henry Pickering has promised to chase up the technicians at Hopkins Orthopaedic – I should have it back for the trial." The trial. Everything seemed to come back to the trial, even the running of King's Lynn and the final preparations for the opening of the lodges at Zambezi Waters could not seduce Craig away from Sally-Anne's bedside and the preparations for the trial. He was fortunate to have Hans Groenewald at King's Lynn and Peter Younghusband, the young Kenyan manager and guide whom Sally-Anne had chosen, had arrived to take over the daily running of Zambezi Waters. Though he spoke to these two every day on either telephone or radio, Craig stayed on in Harare close to Sally-Anne.

Craig's leg arrived back the day before Sally-Anne's discharge from hospital. He pulled up his trouser-cuff to show it to her.

"Straightened, panel-beaten, lubricated and thoroughly reconditioned," he boasted. "How's your head?"

"The same as your leg," she laughed. "Although the doctors have warned me off bouncing on it again for at least the next few weeks." She was using a cane for her ankle, and her chest was still strapped when he carried her bag down to the Land, Rover the following morning.

"Ribs hurting?" He saw her wince as she climbed into the vehicle.

"As long as nobody squeezes them, I'll pull through."

"No squeezing. Is that a rule?" he asked.

"I guess-" she paused and regarded him for a moment before she lowered her eyes and murmured demurely, "but then rules are for fools, and for the guidance of wise men." And Craig was considerably heartened.

umber Two Court of the Mashonaland division of the Supreme Court of the Republic of Zimbabwe still retained all the trappings of British justice.

The elevated bench with the coat of arms of Zimbabwe above the judge's seat dominated the courtroom; the tiers of oaken benches faced it, and the witness box and the dock were set on either hand. The prosecutors, the asses, sors and the attorneys charged with the defence wore long black robes, while the judpe was splendid in scarlet. Only the colour of the faces had changed, their blackness accentuated by the tight snowy curls of their wigs and the starched white swallow-tail collars.

The courtroom was packed, and when the standing room at the back was filled, the ushers closed the doors, leaving the crowd overflowing into the passages beyond.

The crowds were orderly and grave, almost all of them Matabele who had made the long bus journey across the Country from Matabeleland, many of them wearing the rosettes of the ZAPU party. Only when the accused was led into the dock was there a stir and murmur, and at the man dressed in ZAFU colours rear of the court a black wa cried hysterically "Bayete, Nkosi Nkulu!" and gave the clenched-fist salute.

r out The guards seized her immediately and hustled he through the doors. Tungata Zebiwe stood in the dock and watched impassively, by his sheer presence belittling every other person in the room. Even the judge, Mr. justice Domashawa, a tall, emaciated Mashona, with a delicately bridged atypical Egyptian nose and small, bright, birdlike eyes, although vested in all the authority of his scarlet robes, seemed ordinary in comparison. However, Mr. Justice Domashawa had a formidable reputation, and the prosecutor had rejoiced in his selection when he told Craig and SallyAxme of it.

"Oh, he is indeed persona grato and now it is very much in grentio legis, we will see justice done, never fear." While the country had still been Rhodesia, the British jury system had been abandoned. "The judge would reach a verdict with the assistance of the two black-robed assessors who sat with him on the bench. Both these assessors were Shana: one was an expert on wildlife conservation, and the other a senior magistrate. The judge could call upon but the final verdict their expert advice if he so wished would be his alone.

Now he settled his robes around him, the way an ostrich shakes out its feathers as it settles on the nest, and he fixed Tungata Zebiwe with his bright dark eyes while the clerk the charge sheet in English.

of the court read out There were eight main charges– dealing in and exporting the products of scheduled wild animals, abducting and holding a hostage, assault with a deadly weapon, assault with intent to do grievous bodily harm, attempted murder, violently resisting arrest, theft of a motor vehicle, and erty. There were also twelve malicious damage to state prop lesser charges.

By God," Craig whispered to Sally-Anne, "they are throwing the bricks from the walls at him."

"And the tiles off the floor," she agreed. "Good for them, I'd love to see the bastard swing."

"Sorry, my dear, none of them are capital charges." And yet all through the prosecution's opening address, Craig was overcome by a sense of almost Grecian tragedy, in which an heroic figure was surrounded and brought low by lesser, meaner men.

Despite his feelings, Craig was aware that Abel Khori was doing a good businesslike job of laying out his case in his opening address, even displaying restraint in his use of Latin maxims. The first of a long list of prosecution witnesses was General Peter Fungabera. Resplendent in full dress, he took the oath and stood straight-backed and martial with his swagger-stick held loosely in one hand.

His testimony was given without equivocation, so direct and impressive that the judge nodded his approval from time to time as he made his notes.

The Central Committee of the ZAPU party had briefed a London barrister for the defence, but even Mr. Joseph Petal QC could not shake General Fungabera and very soon realized the futility of the effort, so he retired to wait for more vulnerable prey.

The next witness was the driver of the truck containing the contraband. He was an ex-ZIPRA guerrilla, recently released from one of th. rehabilitation centres and his testimony was given, I ire the vernacular and translated into English by the court interpreter.

"Had you ever met the accused before the night you were arrestedf Abel Khori demanded of him after establishing his identity.

"Yes. I was with him in the fighting."

"Did you see him again after the war?"

"Yes."

"Will you tell the court when that was?"

_aWm

"Last year in the dry season."

"Before you were placed in the rehabilitation centrer "Yes, before that."

"Where did you meet Minister Tungata Zebiwe?"

"In the valley, near the great river."

"Will you tell the court about that meeting?"

"We were hunting elephant for the ivory."

"How did you hunt them?"

"We used tribesmen, Batonka tribesmen, and a helicopeld." ter, to drive them into the old minefi object to this line of questioning, my lord." Mr. Petal QC jumped up. "This has nothing to do with the charges."

"It has reference to the first charge," Abel Khori insisted.

"Your objection is overruled, Mr. Petal. Please continue Mr. Prosecutor."

"How many elephant did you kill?" many, many elephant." "Can you estimate how many?"

"Perhaps two hundred elephant, I am not sure." that the Minister Tungata Zebiwe was "And you state there?"

"He came after the elephant had been killed. He came to count the ivory and take it away in his helicopter-2

"What helicopter?"

"A government helicopter." 41 object, your lordship, the Point is irrelevant."

"Objection overruled, Mr. Petal, please continue." When his turn came for crossexamination, Mr. Joseph Petal went into the attack immediately.

u that you were never a member of 11 put it toyo e fighters. That you Minister Tungata Zebiwe's resistanc never, in fact, met the minister until that night on the Karoi road–2

"I object, your lordship," Abel Khori shouted indigthe witness in nantly. "The defence is trying to discredit the knowledge that no records of patriotic soldiers exist and that the witness cannot, therefore, prove his gallant service to the cause."

"Objection sustained. Mr. Petal, please confine your questions to the matter in hand and do not bully the witness."

"Very well, your lordship." Mr. Petal was rosy-faced with frustration as he turned back to the witness.

"Can you tell the judge when you were released from the rehabilitation centre?"

"I forget. I cannot remember."

"Was it a long time or a short time before your arrest?"

"A short time," the witness replied sulkily, looking down at his hands in his lap.

"Were you not released from the prison camp on the condition that you drove the truck that night, and that you aereed to 2I've evidence-" "My lord!" shrieked Abel Khori, and the judge's voice was as shrill and indignant.

"Mr. Petal, you will not refer to state rehabilitation centres as prison camps."

"As your lordship pleases." Mr. Petal continued, "Were You made any promises when you were released from the rehabilitation centre?"

"No. "The witness looked about him unhappily.

"Were you visited in the centre, two days before your release, by a Captain Timon Nbebi of the Third Brigade?"

"No.

"Did you have anyovisitors in the camp?"

"No! NaP "No visitors at all, are you sure?"

"The witness has already answered that question," the judge stopped him, and Mr. Petal sighed theatrically, and threw up his hands.

"No further questions, my lord."

"Do you intend calling any further witnesses, Mr. Khorir Craig knew that the next witness should have been Timon Nbebi, but unaccountably Abel Khori passed over him and called instead the trooper who had been knocked down by the Land-Rover.

Craig felt an uneasy little chill Of doubt at the change in the prosecution's tactics. Did the prosecutor want to protect Captain Nbebi from cross examination? Did he want to prevent Mr. Petal from pursuing the question of a visit by Timon Nbebi to the rehabilitation centre? If this was so, the implications were so Craig forced himself to put his doubts unthinkable, aside.

The necessity for all questions and replies to be translated made the entire court process long-drawn-out and tedious, so it was only on the third day that Craig was called to the witness stand.

and before Abel after Craig had taken the oath, illation, he glanced Khori had begun his exam towards the dock. Tungata Zebiwe was watching him intently and as their eyes locked, Tungata made a sign with his right hand.

In the old days when they had worked together as rangers in the Game Department, Craig and Tungata had developed this sign language to a high degree. During the dangerous work of closing in on a breeding herd to begin the bloody elephant culls during which it had been their -populating duty to destroy surplus animals that were over the reserves, or when they were stalking a marauding cattle-killing pride of lions, they had communicated silently and swiftly with this private language.

Now Tungata gave him the clenched fist, his powerful black fingers closing over the clear pink of his palm in the sign that said "Beware! Extreme danger." The last time Tungata had given him that sign, he had had only microseconds to turn and meet the charge of the enraged lung-wounded lioness as she came grunting in bloody pink explosive gasps of breath out of heavy brush cover, launching herself likea golden thunderbolt upon him, so that even though the bullet from his458 magnum had smashed through her heart, her momentum had hurled Craig off his feet.

Now Tungata's sign made his nerves tingle and the hair on his forearms rise, at the memory of danger past and the promise of danger present. Was it a threat or a warning, Craig wondered, staring at Tungata. He could not be certain, for Tungata was now expressionless and unmoving.

Craig gave him the signal, "Query? I do not understand," but Tungata ignored it, and Craig abruptly realized that he had missed Abel Khori's opening question.

"I'm sorry will you repeat that?" Swiftly Abel Khori led him through his questions.

"Did you see the driver of the truck make any signal as the Mercedes approached?"

"Yes, he flashed his lights."

"And what was the response?"

"The Mercedes stopped and two of the occupants left the vehicle and went to speak with the driver of the truck."

"In your opinion, was this a prearranged meeting?"

"Objection, your lordship, the witness cannot know that."

"Sustained. The witnes will disregard the question."

"We come now to ydhr gallant rescue of Miss Jay from the evil clutches of tl* accused."

"Objection the word "evil"."

"You will discontinue the use of the adjective "evil"."

"As your lordship pleases." After that hand-signal, and during the rest of Craig's testimony, Tungata Zebiwe sat immovable as a figure carved in the granite of Matabeleland, with his chin sunk in his chest, but his eyes never left Craig's face.

As Mr. Petal rose to cross-examine, he moved for the first time, leaning forward to rumble a few terse words. Mr. Petal seemed to protest, but Tungata made a commanding gesture.

"No questions, your lordship," Mr. Petal acquiesced, and sank back in his seat, freeing Craig to leave the witness box without harassment.

Sally-Anne was the last of the prosecution witnesses and, after Peter Fungabera, perhaps the most telling.

She was still limping with her sprained ankle, so that Abel Khori hurried forward to help her into the witness box. The dark shadow of the bruise on her neck was the only blemish on her skin, and she gave her evidence without hesitation in a clear pleasing voice.

"When the accused seized you, what were your feelings?"

"I was in fear of my life."

"You say the accused struck you. Where did the blow land?"

"Here on my neck you can see the bruise."

"You state that the accused aimed the stolen rifle at Mr. Mellow. What was your reaction?

will you tell the court whether you sustained any tAnd other injuries." Abel Khori made the most of such a lovely witness, and very wisely, Mr.

Petal once again declined to crossexamine.

The prosecution closed its case on the evening of the third day, leaving Craig troubled and depressed.

ourite steakhouse, and He and Sally-Anne ate at her fay a bottle of good Cape wine did not cheer him.

even "That business about the driver never having met Tungata before, and being released only on a promise to drive the truck-"

"You didn't believe that?" Sally-Anne scoffed. "Even the judge made no secret of how far-fetched he thought that I was.

After he dropped her at her apartment, Craig walked alone through the deserted streets, feeling lonely and AA

betrayed though he could not find a logical reason for the feeling.

r Joseph Petal QC opened his defence by calling Tungata Zebiwe's chauffeur.

He was a heavily built Matabele, although young, already running to fat, with a round face that should have been jovial and smiling, but was now troubled and clouded. His head had been freshly shaved, and he never looked at Tungata once during his time on the witness stand.

"On the night of your arrest, what orders did Minister Zebiwe give you?"

"Nothing. He told me nothing." Mr. Petal looked genuinely puzzled and consulted his notes.

"Did he not tell you where to drive? Did you not know where you were going?"

"He said "Go straight", "Turn left here,"

"Turn right here"," the driver muttered, "I did not know where we were going." Obviously Mr. Petal was not expecting this reply.

"Did Minister Zebiwe not order you to drive to Tuti Mission?"

"Oh ection, your lordship."

"Do not lead the witness, Mr. Petal." Mr. Joseph Petal was clearly thinking on his feet. He shuffled his papers, glanced at Tungata Zebiwe, who sat completely impassive, and then switched his line of questioning.

"Since the night of your arrest, where have you been?"

"In prison."

"Did you have any visitors?"

"MY wife came."

"No others?" "No. "The chauffeur ducked his head defensively.

"What are those marks on your head? Were you beaten?" For the first time Craig noticed the dark lumps on the chauffeur's shaven pate.

"Your lordship, I object most strenuously," Abel Khori cried plaintively.

"Mr. Petal, what is the purpose of this line of questioning?" Mr. justice Domashawa demanded ominously.

"My lord, I am trying to find why the witness's evidence conflicts with his previous statement to the police." Mr. Petal struggled to obtain a clear reply from the sulky and uncooperative witness, and finally gave up with a gesture of resignation.

"No further questions, your lordship." And Abel Khori rose smiling to cross-examine.

"So the truck flashed its lights at you?"

"Yes."

"And what happened then?" I do not understand."

"Did anybody in the Mercedes say or do anything when you saw the truck?"

"My lord-2 Mr. Petal began.

"I think that is a fair question the witness will answer." all, and The chauffeur frowned with the effort of rec "Comrade Minister Zebiwe said, "There it then mumbled, is pull over and stop.""

""There it is'T Abel Khori repeated slowly and clearly.

""Pull over and stop'I That is what the accused said when he saw the truck, is that correct?"

"Yes. He said it." No further questions, your lordship." all Sarah Tandiwe Nyoni." Mr. Joseph Petal introduced his surprise witness, and Abel Khori frowned and conferred agitatedly with his two assistant prosecutors. One of them rose, bowed to the bench and hurriedly left the court.

Sarah Tandiwe Nyoni entered the witness stand and took the oath in perfect English. Her voice was melodious and sweet, her manner as reserved and shy as the day that Craig and Sally-Anne had first met her at Tuti Mission.

She wore a lime-green cotton dress with a white collar and simple low-heeled white shoes. Her hair was elaborately braided in traditional style, and the moment she finished reading the oath, she turned her soft gaze onto Tungata Zebiwe in the dock. He neither smiled nor altered his expression, but his right hand, resting on the railing of the dock, moved slightly, and Craig realized that he was using the secret sign-language to the girl.

"Courage!" said that signal. "I am with you!" And the girl took visible strength and confidence from it. She lifted her chin and faced Mr. Petal squarely.

"Please state your name."

"I am Sarah Tandiwe Nyoni," she replied.

Tandiwe Nyoni, her Matabele name, meant' Beloved Bird'and Craig translated softly to Sally-Anne.

"It suits her perfectly," she whispered back.

"What is your profession?"

"I am the headmistress'bf Tuti State Primary School."

"Will you tell the c&lrt your qualifications." Joseph Petal established swiftly that she was an educated and responsible young woman. Then he went on: "Do you know the accused, Tungata Zebiwe?" She looked at Tungata again before answering, and her face seemed to glow. "I do, oh yes, I do, she whispered huskily.

"Please speak up, my dear." 11 know him."

"Did he ever visit you at Tuti Mission Station?"

"Yes" she nodded.

"How often?"

"The Comrade Minister is an important and busy man, I am a school-teacher-" Tungata made a small gesture of denial with his right hand. She saw it and a little smile formed on her perfectly sculptured lips.

"He came as often as he could, but not as often as I would have wished."

"Were you expecting him on the night in question?" I was." "Why?) "We had spoken together, on the telephone, the previous morning.

He promised me he would come. He said he would drive up, and arrive before midnight." The smile faded from her lips, and her eyes grew dark and desolate. "I waited until daylight but he did not come."

"As far as you know was there any particular reason that he was going to visit you that weekend?"

"Yes." Sarah's cheeks darkened, and Sally-Anne was fascinated. She had never seen a black girl blush before.

"Yes, he said he wished to speak to my rathe r. I had arranged the meeting."

"Thank you, my dear," said Joseph Petal gently.

During Mr. Petal's examination, the prosecutor's assistant had slipped back into his seat and handed Abel Khori a handwritten sheet of notes. Abel Khori was holding these in his hand as he rose to crossexamine.

"Miss Nyoni, can you tell the court the meaning of the Sindebele word, Isifebi?" Tungata Zebiwe growled softly and began to rise, but the police guard laid a hand on his shoulder to restrain him.

it means a harlot," Sarah answered quietly.

"Does it not also mean an unmarried woman who lives with a man-" "My lord!" Joseph Petal's plea was belated but outraged, and Mr. Justice Domashawa sustained it.

"Miss Nyoni," Abel Khori tried again. "Do you love the accused? Please speak up. We cannot hear you." This time Sarah's voice was firm, almost defiant. "I do."

"Would you do anything for him?"

"I

would."

"Would you lie to save him?"

"I object, your lordship. "Joseph Petal leapt to his feet.

"And I withdraw the question." Abel Khori forestalled the judge's intervention. "Let me rather put it to you, Miss Nyoni, that the accused had asked you to provide a warehouse at your school where illegal ivory and leopard skins could be stored!"

"No." Sarah shook her head. "He never would-"

"And that he had asked you to supervise the loading of those tusks into a truck, and the despatch of the truck-" "No! NoVshe cried.

"When you spoke to" him on the telephone, did he not order you to prepare a shipment of-2

"No! He is a good man, Sarah sobbed. "A great and good man. He would never have done that."

"No further questions, your lordship." Looking very pleased with himself, A441 Khori sat down and his assistant leaned over to whisp! his congratulations.

"call the accusd, the Minister Tungata Zebiwe, to the stand." That was a risky move on Mr. Petal's part. Even as a layman, Craig could see that Abel Khori had shown himself to be a hardy scrapper.

Joseph Petal began by establishing Tungata's position in the community, his services to the revolution, his frugal life-style.

"Do you own any fixed property?"

"I own a house in Harare." (Will you tell the court how much you paid for it?"

"Fourteen thousand dollars."

"That is not a great deal to pay for a house, is it?"

"It is not a great deal of house." Tungata's reply was deadpan, and even the judge smiled.

"A motor-car?"

"I have a ministerial vehicle at my disposal." "Foreign bank accounts?"

"None."

"Wives?"

"None–2 he glanced in the direction of Sarah Nyoni who sat in the back row of the gallery" yet," he finished.

"Common-law wives? Other women?"

"My elderly aunt lives in my home. She supervises my household."

"Coming now to the night in question. Can you tell the court why you were on the Karoi road?"

"I

was on my way to Tuti Mission Station."

"For what reason?"

"To visit Miss Nyoni and to speak to her father on a personal matter."

"Your visit had been arranged?"

"Yes, in a telephone conversation with Miss Nyoni."

"You have visited her before on more than one occasion?" "That is so."

"What accommodation did you use on those occasions?" "There was a thatched ffidlu set aside for my use."

"A hut? With a sleeping-mat and open fire?"

"Yes.

"You did not find such lodgings beneath you?"

"On the contrary, I enjoy the opportunity of returning to the traditional ways of my people."

"Did anyone share these lodgings with you?"

"My driver and my bodyguards."

"Miss Nyoni did she visit you in these lodgings?"

"That would have been contrary to our custom and tribal law."

"The prosecutor used the word isifebi what do you make of that?"

"He might aptly apply that word to women of his acquaintance. I know nobody whom it might fit." Again the judge smiled, and the prosecutor's assistant nudged Abel Khori playfully.

"Now, Mr. Minister, was anybody else aware of your intention of visiting Tuti Mission?"

"I made no secret of my intention. I wrote it down in MY desk-diary."

"Do you have that diary?"

"No. I requested my secretary to hand it over to the defence. It is, however, missing from my desk."

"I see. When you ordered your chauffeur to prepare the car, did you inform him of your destination?"

"I did."

"He says you did not."

"Then his memory is at fault or has been affected." Tungata shrugged.

"Very well. Now, on the night that you were driving on the road between Karoi ajl Tud Mission, did you encounter any other vehicle?", "Yes. There was a– truck parked in darkness, off the road, but facing in our direction."

"Will you tell the court what transpired then?"

"The truck-driver switched on his lights, and then flicked them three times.

At the same time he drove forward into the road."

"In such a way as to force your car to halt?"

"That is correct."

"What did you do then?"

"I

said to my driver, "Pull over but be careful. This could be an ambush.""

"You were not expecting to meet the truck then?"

"I was not." "Did you say, "There it is! Pull over!"I "I did not."

"What did you mean by the words: "This could be an ambush'T "Recently, many vehicles have been attacked by armed bandits, shufta, especially on lonely roads at night."

"So what were your feelings?"

"I was anticipating trouble." "What happened then?"

"Two of my bodyguards left the Mercedes, and went to speak to the driver of the truck."

"From where you were seated in the Mercedes, could you see the truck-driver?"

"Yes. He was a complete stranger to me. I had never seen him before."

"What was your reaction to this?"

"I was by this time extremely wary."

"Then what happened?" "Suddenly there were other headlights on the road behind us. A voice on a bull-horn ordering my men to surrender and throw down their arms. My Mercedes was surrounded by armed men and I was forcibly dragged from it."

"Did you recognize any of these men?"

"Yes. When I was pulled from the Mercedes, I recognized General Fungabera."

"Did this allay your suspicions?"

"On the contrary, I was now convinced that I was in danger of my life."

"Why was that, Mr. Minister?"

"General Fungabera commands a brigade which is notorious for its ruthless acts against prominent Matabele-"

"I object, your lordship the Third Brigade is a unit of the regular army of the state, and General Fungabera a well-known and respected officer, "Abel Khori cried.

"The prosecution is totally justified in its objection." The judge was suddenly trembling with anger. "I cannot allow the accused to use this courtroom to attack a prominent soldier and his gallant men. I cannot allow the accused to stand before me and disseminate tribal hatreds and prejudices. Be warned I will not hesitate to find you guilty of gross contempt if you continue in this vein." Joseph Petal took fully thirty seconds to let his witness recover from this tirade.

"You say you felt that your life was in danger?"

"Yes," said Tungata quietly.

"You were strung up and on edge?"