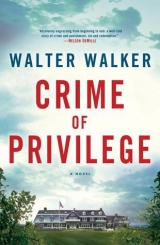

Текст книги "Crime of Privilege"

Автор книги: Walter Walker

Соавторы: Walter Walker

Жанры:

Триллеры

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 26 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

1

.

CAPE COD, September 2008

IT WAS AFTER 8:00 ON THE NIGHT FOLLOWING JAMIE GREGORY’S death when I got to South Station in Boston. The shooting was one of two major stories in the newspapers. The other had to do with the collapse of a pair of financial institutions, including the very one that had employed Jamie. It seemed something had gone terribly wrong with sub-prime mortgages. The newspapers thought the two stories were related.

There was a car and driver waiting for me when I got off the train. I did not know the driver, and he did not ask me any questions. If he knew what I had been through, he did not acknowledge it. We rode in silence for the hour and fifteen minutes it took to get from Boston to Barnstable.

The triumvirate were still in the office when I arrived: Mitch in his short-sleeved shirt, Dick with his belly hanging over his belt, Reid with his steel-gray eyeglasses. None of them was concerned with my physical or mental well-being. But they very much wanted to hear what I had to say. I did what I had tried and failed to do in New York, laid out the entire case against Jamie, laid it out painstakingly, starting in Palm Beach. Dick showed shock. Mitch looked uncomfortable. Reid was impassive.

“According to New York,” Reid said when I was done, “they contacted Mr. Powell in Delaware and he claims not only to have never employed a Roland Andrews but never to have heard of him. NYPD says they have searched databases for the entire country and can come up with no one by that name who fits your description.” He picked up a piece of paper, what appeared to be a faxed letter. “They tell me,” he said, holding it by its corner, letting it swing back and forth between us, “there is no record of a Roland Andrews ever serving in the Special Forces.”

“Check the fingerprints on the gun,” I urged. “Andrews had to have served in some branch of the armed forces. There ought to be a match somewhere.”

“There were no prints on the gun,” Reid said. He did not act surprised or even disappointed.

“We think,” said Dick O’Connor, his round face filled with innocent goodwill, “you might be best off going with the story that the shooter was a disgruntled investor.”

When I didn’t say anything, he went further. “Big collapse on Wall Street yesterday. A lot of angry people out there. People who lost everything.”

I looked at the others. Reid appeared to be nodding, although with such economy of movement it was hard to tell. Mitch was neither speaking nor moving. He was just staring.

2

.

IT WAS DECIDED I WOULD TAKE A LEAVE OF ABSENCE, WITH PAY. There would be no explanation and, I was told, if I was smart I wouldn’t offer one myself. “Let the New York cops continue their investigation,” said Reid. “They haven’t disclosed your identity in any way. Leave it at that. The alternative, you know, the alternative is they parade you in front of the bimbo, let her identify you.”

When I pointed out that it had been my job to find the killer of Heidi Telford and that I had done just that, Dick O’Connor shook his head until his jowls shimmied. “What you got is not enough to meet our burden of proof,” he said. “You know how it is: We’ve got to show beyond a reasonable doubt. But here, what do you have, really? Some gal in New York says it wasn’t Peter; you figure that means it was Jamie. You go to Jamie, try to beat a confession out of him. Only he doesn’t confess. ’Least, nobody hears him confess.”

He shrugged helplessly. “Which means, all we’ve got is you.”

“And,” added Reid, “you’re tainted.”

3

.

I WENT HOME AND I WAITED. I WASN’T SURE FOR WHAT.

Every day I listened to the radio: the local Cape stations, WBZ in Boston, NPR. The airwaves were filled with talk about the economic crisis. Every day I read The New York Times, The Boston Globe, the Cape Cod Times. There were articles about Jamie’s death, about the funeral, about his family. There continued to be speculation about the connection between his killer and the money that Jamie had lost for investors. Both the police and the FBI claimed to be investigating. “But,” explained one NYPD spokesman, “there were just so many people who were wiped out, it may take years.”

Every day I got out my bike and rode as far as I could, for as long as I could.

I HAD A CALL from Barbara. She wanted to know how I was doing.

She also wanted to tell me that with my office door closed and locked, there were rumors flying around the office about where I was and what was happening to me. Sean Murphy, she said, was telling people it was not just a coincidence that I had disappeared on the very day Jamie Gregory was shot.

I hung up with Barbara and immediately called Dick O’Connor. He told me I needed to lie low, let the process take its course. I repeated what I had heard about the rumors and Dick agreed that it was unfortunate. He said he would speak to Sean and urged me to be patient. “Things are being taken care of, Georgie,” he insisted.

THE RESULTS OF the autopsy were released. It turned out Darra Lane had done me an enormous favor. In her press conference, in her stories to the police, on television and in magazines, she had insisted that a man in a suit had shot Jamie Gregory from just a couple of feet away. The autopsy confirmed that Jamie had been shot from a distance, at least twenty-five feet, said the coroner, who commented that it was a rather remarkable feat of marksmanship for a nine-millimeter pistol. The shooter must have been well trained, he said.

I waited for a call from Dick. It didn’t come. I tried calling him. He wasn’t available. His secretary said he would call me back. He didn’t.

I placed three more calls: one to Dick, one to Reid, one to Mitch. Nobody took them.

4

.

I RODE MY BIKE ALL THE WAY TO PROVINCETOWN. I HAD NOT MEANT to go that far. I had ridden the Rail Trail, taken the Chatham route, then continued on through Orleans until I got to the roundabout that marked the transition from Mid-Cape to Lower Cape. I could have gone one hundred eighty degrees around the rotary, then on to Rock Harbor, where I could have stopped and looked at the fishing boats, maybe bought a lobster roll at a place called Cap’t Cass on the edge of the Harbor parking lot, then gotten back on the Brewster leg of the Rail Trail and returned to my car in Dennis. This time of year I wasn’t sure Cap’t Cass was still open, and so I decided to head east instead, go to Arnold’s Lobster and Clam Bar along Route 6. It was closed for the season, so I kept going, through Eastham, with a vague idea that there were more roadside lobster shacks and one of them was bound to be open. I kept riding through Wellfleet, and by the time I got to Truro I decided to go all the way.

It was almost dark when I got to the end of the continent. I wasn’t going to be able to ride back. I didn’t have a light, didn’t even have a windbreaker, and it was getting cold. I booked a room at a motel at the far end of town, out on a jetty, the very edge of the world.

IT WAS FOGGY WHEN I got up in the morning, and still cold. I had walked partway along Commercial Street the night before, looking for something to eat. I had gotten some catcalls from men who had enjoyed my spandex outfit, and now I was going to have to make the walk again if I wanted to buy something warm to wear for the long ride back.

I reminded myself that the catcallers were unlikely to be out first thing in the morning and left the dankness of the room to begin my trek. I had walked for no more than thirty seconds when a black vehicle that looked like a giant Jeep began blinking its lights. The clouds were at ground level and all around me. I could hear foghorns out on the water, and I could not see one hundred feet in any direction, but I could see those flashing headlights. I stopped, thinking it might be police or a national park ranger, somebody warning me it was dangerous to be trying to navigate on foot when visibility was this poor. Maybe warning me it was dangerous to walk through town dressed the way I was.

But this was P’town. People could wear anything they wanted.

The vehicle’s door opened, and I realized it was not a Jeep but a Hummer, the smaller model, the one they called the Hummer 3. “Hey, Georgie!” a voice called. A male voice.

I squinted, trying to get a better look.

The man was holding something in his hand, something like a bag. I remembered the hood in Tamarindo and it occurred to me that I should run. Except there was nothing behind me but the motel and the long rock jetty. I stood my ground while the man approached. A big man, wearing shorts. Red shorts. Nantucket Reds, knee-length, salmon-colored, popular among the summer crowd on the islands. The object in the man’s hand was a piece of dangling cloth, a blanket maybe, or a jacket. Below the shorts he was wearing Top-Siders; above them he had on a sweater and a polo shirt with the collar popped. The man was grinning. He was grinning because he knew me and he had not seen me in twelve and a half years.

He stopped when he got an arm’s length away from me. He did not try to embrace. He did not even offer his hand. What he offered was the cloth, which turned out to be a sweatshirt. A crimson sweatshirt.

“Penn guy like you probably doesn’t want this, but it’s better than freezing your ass off.” He tossed it to me.

I caught the sweatshirt in one hand, looked down at it, saw the word “Harvard” emblazoned with white letters and continued holding it, dumbstruck.

“Want some coffee?” He slung a thumb over his shoulder. “I got a whole Thermos. Got some Dunkin’ Donuts, too, if you’re hungry.”

I was hungry. I did want some coffee. I said, “No, thank you, Peter.”

He nodded. He looked as if he was going to try some other friendly acts, suggestions, gestures, and then he wiped the condensation from his brow and said, “I was wondering if I could talk to you.”

“We’re talking now, aren’t we?” I still had not put on the sweatshirt.

“I guess you don’t want to get in the car, huh?” Then he answered himself. “Yeah. I don’t blame you. You’ve been through a lot because of us, and that’s what I wanted to talk about. To apologize, really. Listen, can we go for a walk at least? You mind? How about out on that jetty?”

Go out on the jetty. In the fog. With Peter Gregory Martin.

“How about we go into town?” I said.

“Yeah.” He nodded. “We could. Except you can never tell who’s around.” He looked around. “Always seems to be somebody with a camera when you least expect it.” He inclined his head toward the jetty as if it were the only possible place for two men to walk if they wanted a little privacy.

“Which begs the question: What are you doing here, Peter? Outside my motel at eight in the morning? You follow me here?”

“Not really.” He grinned some more, harder this time. It was still a friendly grin, not a sick one like Jamie’s, but not a charming one like the Senator’s, either.

I tried to think. Nobody had followed me. At least I had not seen anybody follow me. “Peter, I didn’t know I was coming here. It’s just where I ended up.”

He waved his hand in the direction of Route 6, as if that was where somebody had seen me. Of course, it was also the direction of everything else in the country, everything except the motel itself. I looked at the motel office. He saw me looking.

“Nah,” he said, interpreting. “What, do you think we have some big network of informers or something? You check in someplace and the desk clerk immediately calls us up?”

He acted like it was a joke, but that was exactly what I was thinking. It didn’t make a lot of sense, but neither did the idea that someone could have been with me on a trail that did not allow motor vehicles and then tailed me all along Route 6, where I had not seen a single other cyclist. And then it came to me.

“You put a tracking device on my bike, didn’t you?”

“C’mon, Georgie.” Peter Martin swatted me playfully on the shoulder.

I recoiled. “Where is it? Under the seat?”

Peter stopped grinning. He looked away. There was not much he could look at. “I don’t do these things myself, George.”

“You wanted to talk to me, you could have come to my house. Called me on the phone.”

“I wanted to see you in person. That’s why I came across country. Didn’t think it was going to be fucking winter.” He wiped his brow a second time. The fog was so wet it was matting our hair into strands that plastered our skulls and created little follicular runways for drops of water. “I didn’t want to come to your house because, like I said before, you never know who’s around.”

Peter Martin did not want to be seen with me. Peter Martin was standing with me in a fog so thick there could have been a troop of soldiers arrayed fifty yards from us and I would not have known.

“Could be anyone,” I said.

He agreed.

“Could even be Josh David Powell.”

“His people, yeah.”

“All kinds of folks following me, aren’t there, Peter?”

“It’s part of what I want to apologize about. Look, can we please walk? Just in case Powell does have somebody around, can we not stand here like this?”

He wanted to go on that jetty. I looked and couldn’t see anything. Just the first few gray-black boulders that made up the riprap that curved its way into the ocean. A foghorn sounded again, warning me away.

Prosecutor found dead floating off Provincetown jetty. He must have slipped on the rocks and hit his head. He was wearing bicycle shoes with metal plates on the soles.

“No,” I said. “This is as good a place as any.”

Prosecutor found dead in parking lot. Strangled, garroted, beaten to a pulp. I would take Peter down with me. I would make him pay. Hit me, motherfucker, and I will carve you up. With what, I didn’t know. My fingers, if that was all I had.

Peter sighed. He shrugged. “At least put on that sweatshirt if we’re going to stand here. You don’t need to freeze to death.”

Prosecutors don’t freeze to death in September on Cape Cod. Nevertheless, I draped the sweatshirt over my shoulders, crossed my arms, and waited.

“I know,” Peter said, starting slowly, “that you were there when Jamie was murdered.” He threw up his palm quickly to stop me from responding. “I even know what you said to him. I’m not here to argue about it. What I am thinking, however, what the family’s thinking, is, okay, Jamie’s dead, what good does it do to drag all this out?”

Now? Did he want me to answer now? No.

“Powell and his thug there,” he went on, “they’re not going to admit what they did, and we’re asking ourselves if we really want to go after them.”

Yeah, right. And bring into the open why Powell’s man would want to shoot Jamie. I might have been sneering as I stood in the street at the end of the world.

“So,” he said, “the next thing we have to consider is you, and how you feel about it. And we’re thinking, you know, we’ve always been able to count on Georgie, count on his discretion. So what about now?”

“I’ve already talked, Peter.”

“Yes. But you’ve talked to the police, to the folks in the D.A.’s office. That can all be taken care of. The question is, what do you really want to do?”

Peter, his neck extended, his head pointing toward me, seemed really to want to know. It took me a moment to understand he was not just asking my opinion, my preference, he was offering me something.

“What do you have in mind?” I said.

“You know,” he answered, his eyes on mine, keeping contact, “Mitch White would like nothing better than to get out of here, go back to D.C. He’s up for reelection in a couple of weeks and everybody figures he’s a shoo-in, but the right job came along, he’d leave the Cape in a minute.”

“Senate Judiciary Committee, perhaps?”

“Maybe even better than that. Democrat gets elected to the White House, a number of favors can be called in.” Peter shrugged. That’s the way things work, he was saying.

“And you’re thinking perhaps I might like to take Mitch’s place, be district attorney for the Cape and Islands.”

“Somebody’s got to. If the door’s thrown open at the last minute, whoever is the best organized, has the best backing, is going to get it.”

“Suppose somebody else is already out there getting ready? Somebody independent of the Gregory family?”

“That can be taken care of.” Peter shifted his feet, moved in a little closer as if to make sure that nobody lurking in the fog would hear him. “You want the support of the Macs, all you have to do is come out in favor of the Mashpee Indian casino and they’re yours.”

“It’s all arranged?”

“It could be.”

“I just have to keep my mouth shut about Jamie.”

“Look, George.” Peter kept his eyes focused on mine. “I don’t blame you for what happened there, in New York. Nobody does. You did what you thought should be done.” He reached out to touch my shoulder.

Once again I twisted out of the way and he lowered his hand.

“Jamie was a difficult person,” he said, a touch of sadness in his voice. “Brilliant, but he was missing a—I don’t know, a moral compass, I guess you’d call it.”

“Unlike you.”

“Yeah, well, I know what you’re talking about, George. I’ve got a lot of guilt built up in me about that.”

“About Kendrick Powell, you mean.” I wanted him to say it.

“I was drunk. I was young. None of that is an excuse, but it’s true. And you pulled me off her, George, and for that I’ll forever be grateful. I mean it.” He once again started to reach out to me and then drew back his hand before I could move.

I said, “You guys raped her, Peter. And then you lied and insisted it never happened.”

His face warped with confusion, as if he had misheard. “We tried to make it up to her,” he said. “We really did. Offered her a great deal of money, in fact. Her father would have none of it. So that’s when we had to ask ourselves—”

He hesitated, gauging what he should say, how he should say it. Small drops of water were making their way down his forehead.

“—what good was it going to do to confess? What, we maybe go to prison? At the least, the whole world was going to know. The family’s name gets dragged through the mud. My uncle once again is kept from doing all the good things he could do for the country. Jamie and I are kept from doing all the good things that we, as Gregorys, could do.”

“Like sell worthless mortgages to friends who are trusting you with their life savings?”

This was not going the way Peter Martin had envisioned. He shifted his weight, stuck his hands in the pockets of his shorts, moved his eyes from mine to the tarmac at our feet. “Yeah, well, that was Jamie.”

“The one whose honor we’re trying to preserve.”

“Not just his, George. I mean, I tried, I really tried to dedicate myself to the betterment of humanity.” His head lifted sharply, as if appalled at his own words. “I don’t want that to sound pretentious, George. It’s just … there were lots of things I could have done, but I chose to go to med school and to specialize in infectious diseases, and then I chose to go to San Francisco and work with AIDS victims. I didn’t have to do any of that.”

“You also didn’t have to help Jamie dispose of Heidi Telford’s body and pretend he didn’t kill her.”

Noises were coming out of Peter Martin. Noises that made me think of a steam engine. They were, I realized, rapid breaths of air. He was acting as if I had just punched him in the gut. Peter, the big bear, whose arm had been soft when I squeezed it in Palm Beach, who looked even softer now, did not know what to do. I could see him searching for words. I could see words starting to form in his mouth and then disappear.

“When you’re in my family,” he said at last, “and so many tragic things have happened, you learn from the time you’re able to walk that you have to stick together. That’s all we have—”

“That and money and connections and opportunity and rules that apply to everyone else except you.”

Peter started to defend himself and I cut him off. “You and Jamie treated Heidi Telford the same way you treated Kendrick Powell. She didn’t count. Not when it came to your pleasure, not when it came to your well-being. Justify it in your own mind all you want, you fat fuck. You molested and raped a young woman, then watched her life go down the drain because you didn’t want people to know what you had done and because as far as you were concerned she wasn’t worth what a Gregory was worth. Then three years later you let your cousin bash in the head of another young woman and you treated her like she wasn’t worth anything, either.”

I took the sweatshirt off my shoulders and threw it in his face. “You didn’t care about Kendrick, you didn’t care about Heidi, you didn’t care about what you did to their parents. All you cared about was how you looked and when you tell me now about what a great humanitarian you are, I know the truth.” I jammed my thumb into my chest. “Me, Peter. I know the truth.”

The sweatshirt had slid the length of his body until he caught it somewhere around his stomach. Now he held it there while he stared at me in disbelief. His was the face of a man looking at the unknown; as if, standing here at the end of the continent, he had just discovered that the world really was flat, that the waters were rushing off the edge and taking him with them.

Very slowly, he began to back away.