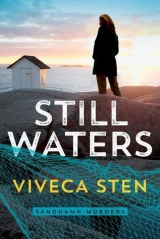

Текст книги "Still Waters"

Автор книги: Viveca Sten

Жанры:

Триллеры

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 2 (всего у книги 24 страниц)

CHAPTER 5

Nora cycled home deep in thought. She wondered if the man who had died had been a resident or a total stranger. If he lived on Sandhamn, then she should have heard that someone was missing. The island was small enough for most people to keep an eye on each other. The social network was strong. But she hadn’t heard a thing.

As she lifted Simon down and parked the bike by the fence, she saw her next-door neighbor, Signe Brand, watering her roses. The most glorious roses covered the south-facing wall of Signe’s house, pink interspersed with red. The rose bushes were several decades old, their stems as thick as a wrist.

Signe, or Auntie Signe as Nora called her when she was little, lived in the Brand house, one of the most beautiful houses on the island, right in the middle of Kvarnberget, just by the inlet to Sandhamn. When the old windmill that had stood on Kvarnberget was moved in the 1860s, Signe’s grandfather, the master pilot Carl Wilhelm Brand, saw an opportunity to make use of the land. After many years he built a truly imposing house right at the top of the hill.

Although the fashion at the time was to build houses close together in the village in order to protect each other from the wind, the master pilot built his house so that it stood alone in solitary majesty. It was the first thing visitors saw when the steamboat docked in Sandhamn, a landmark for all those who came to the island.

The master pilot had skimped on nothing when the house was being built. He used only the finest material. The National Romantic style was fully embraced, with narrow roof projections, wide decorative bargeboards, and gently curving lines in the attic and bay windows. Inside were lavish tiled stoves, specially ordered from the porcelain factory in Gustavsberg, and a huge claw-foot bathtub in what was an unusually modern bathroom for the time. There was even an indoor toilet, which provoked great surprise among the neighbors, who were used to the inconvenience of the outhouse.

Some of them had shaken their heads, muttering something about fancy city ways, but the master pilot had taken no notice. “I’ll shit where I like,” he had roared when the gossip reached him.

Signe had bought herself a television after resisting for many years, but that was the only thing that didn’t fit in with the style of the house. Everything was so beautifully preserved it was barely noticeable that a hundred years had passed since the house was furnished.

These days, Signe lived alone in the house with her dog, a Labrador named Kajsa. From time to time she complained about the cost of everything, but each time some fresh outsider tried to tempt her with an amazing offer for what had to be one of Sandhamn’s most beautiful buildings, she snorted and sent them packing.

“This is where I was born, and this is where I’m going to die,” she would say without a shred of sentimentality. “No rich kid from Stockholm is moving in here.”

Signe loved the house she had inherited, and Nora could understand why. When she was little, Signe had been like an extra grandmother, and Nora felt just as much at home in her house as in her parents’.

“Did you hear about what happened?” she asked Signe.

“No, what?” Signe said, putting down the watering can. She straightened up and came over to the fence.

“Somebody drowned—they found a body over on the west beach. The police are out in force.”

Signe looked at her in surprise.

“You can imagine how wound up the parents at the swimming school were,” Nora said.

“Somebody’s dead, is that what you said?”

“Yes. I bumped into Thomas down by Westerberg’s. He’s here to investigate the death.”

“Do they know who it is? Did you recognize the body?”

“I wasn’t there. Thomas said it was a man, and the body was in a really bad state. Apparently it’s been in the water for several months.”

“So Thomas is here on police business. To think he’s so grown up,” said Signe.

“So am I. He’s only a year older than me,” Nora said with a grin.

“It’s still hard to grasp. Time goes so quickly.” Signe looked sad. “I can hardly believe you’ve got children of your own. It seems like just yesterday you were as small as Adam and Simon.”

Nora smiled, said good-bye, and went inside. She loved her house, which she had inherited several years earlier from her grandmother. It wasn’t all that big, but it was charming and had held up really well, considering it was built in 1915. On the ground floor there was a large kitchen and a big room that served as a TV room and playroom as well as a sitting room for the adults.

A small tiled stove with a delicate flower pattern had been preserved over the years. In the winter it warmed the whole ground floor. Since there were power outages occasionally in the archipelago, it was a useful asset.

Upstairs there were two bedrooms, one for her and Henrik and one for the boys. When they’d moved in they had treated the house to a complete and much-needed renovation of the kitchen and bathroom. Nothing too over the top, just enough to make it functional and inviting.

The best thing about the house, however, was the sunny, old-fashioned greenhouse; she had filled the windowsills with Mårbacka pelargoniums. From there, it was possible—with a little bit of effort—to catch a glimpse of the sea to the west. The main thing visible, however, was Signe’s house, rising up on the hill and making Nora’s place look like a little hut by comparison.

“Hi, we’re home,” Nora shouted up the stairs to Henrik, but the house was silent. She had been nursing a faint hope that he might have gotten Adam up while she was out with Simon, but obviously they were still asleep. Despite the fact that Henrik was used to going without sleep for many hours when he was on duty at the hospital, he had no problem making up for it when they were on vacation.

With a sigh she started up the stairs.

“Boo!”

Nora jumped as Adam leaped out from behind the bathroom door.

“Were you scared?” He was beaming. “Daddy’s still asleep. But I made my bed.”

Nora gave him a hug. She could feel his ribs under his T-shirt. Where had her chubby baby gone, and where had this skinny little creature come from?

“Come on, you need something to eat before your swimming lesson.”

She took him by the hand and went down to the kitchen. As she got out the fresh rolls she’d bought on the way home, Adam set the table.

“Don’t forget your insulin, Mom,” he reminded her.

Nora smiled and tried to sneak an extra hug. He was a typical big brother, responsible and caring. Since he’d been old enough to understand how important it was for a type 1 diabetic like her to take her insulin before every meal, he had made it his job to remind her. Whenever she was a little careless, particularly when they weren’t at home and were eating snacks, he got terribly anxious and told her off.

She opened the fridge and took out the pen-like device she used to inject herself with insulin. With an exaggerated gesture she held it up and showed it to Adam.

“There we are, General! Mission accomplished!”

With practiced hands she fitted the ampule to the syringe and injected the insulin into her stomach just below the navel. To her relief it appeared that neither Simon nor Adam showed any sign of developing diabetes, but it was impossible to be completely certain until they were fully grown.

She could hear Simon running in to Henrik and doing his best to wake him up by jumping up and down on the bed, which was fine by her. If she took Simon early in the morning, Henrik could at least make sure Adam got off to his lesson. And besides, Thomas was coming for coffee.

CHAPTER 6

The police station on Sandhamn shared its accommodation with the post office. It was a buff-colored building that looked like a typical vacation home, situated just below the old sandpit, known as Gropen, or the Hollow.

Inside was a modern office with a dozen workstations and a meeting room. About fifteen people worked there, mainly women, and they dealt with most things, from violent crime and robbery to stolen cell phones and bicycles. The station opened early in the morning and didn’t close until ten o’clock at night.

As the station was linked to the police intranet, it was no problem for Thomas to use one of the terminals to write up and send his report on the dead man. There wasn’t much to say, apart from the fact that they had found a body, cause of death unknown.

While he was there, he took a look at the register of missing persons.

In the district of Stockholm, two men had been reported missing. One was retired, aged seventy-four, with dementia. The report had come in two days ago.

He’s probably lost in some clearing in the forest, poor guy, thought Thomas. If they didn’t find him soon, he’d die of exhaustion and dehydration. It wasn’t particularly unusual.

The other was a man in his fifties, Krister Berggren, who worked in an off-license that was part of the state-owned alcohol monopoly, Systembolaget, commonly known as Systemet. His employer had contacted the police at the beginning of April when he’d failed to turn up for work for ten days. He hadn’t been seen since Easter weekend, the last week in March. Krister Berggren was of medium height, had dark-blond hair, and had worked at Systemet since 1971, immediately after leaving school, if Thomas’s calculation was correct.

Thomas took out his cell phone and called Carina, the DCI’s surprisingly pretty daughter, who worked as an administrative assistant with the police in Nacka as experience for her application to the police training academy.

“Hi, Carina, it’s Thomas. Can you get in touch with the pathologists and tell them the body that’s coming in might be a match for one Krister Berggren from Bandhagen, who’s been missing for a few months?” Thomas gave her Berggren’s ID number and address. “And you might as well find out who we’ll need to contact if it is a match. If we’re lucky, they might find a driver’s license or ID card on him when they do the preliminary exam.”

He looked back at the description of Krister Berggren on the screen. Through the window he could hear the laughter of a group of children cycling past. Another reminder that it was summer, and he’d soon be able to take off to Harö, the only place he’d found a sense of calm since Emily died. He suddenly felt a powerful longing to be sitting alone in peace on the jetty.

“It would be nice if we could solve the case this quickly and easily,” he said to Carina. “It’s nearly vacation time, after all.”

THURSDAY, THE FIRST WEEK

CHAPTER 7

When Thomas walked into Nacka station on Thursday morning, Carina was ready and waiting. She pushed over the report that had just arrived, stamped with the pathology department logo.

“This just came in. The dead man on Sandhamn was Krister Berggren, as you thought. His wallet was in his pocket, and it was possible to make out the text on his driver’s license, even though it had been in the water for so long.”

As Thomas read through the report, Carina studied him. Ever since she’d started at Nacka she had been stealing glances at him. There was something about him that attracted her, but she couldn’t quite put her finger on it.

He had thick blond hair, cut very short, and she had the feeling it would grow wild if it weren’t tamed. There was something outdoorsy about him; it was obvious he liked to spend time in the fresh air. Around his eyes there was a mass of tiny lines, from years of squinting into the sun. He was fit and tall. She was quite a bit shorter than Thomas.

He was reputed to be an excellent policeman, sympathetic and fair. An honorable man who was good to work with. His likeable personality made him a popular member of the team, despite the fact that he kept a good deal of distance. He didn’t allow anyone to get too close.

According to what Carina had heard, he had lost a child about a year ago. After that, there had been no hope for his marriage, and it had ended in divorce. There had been talk in the office about the little girl who had died of sudden infant death syndrome, but nobody knew the details.

For a long time he had been very depressed, but lately his spirits had begun to rise. At least if you believed the office gossip.

She hadn’t been with anyone special recently, just dated a little. Boys her own age who bored her. Thomas—who was approaching forty—was completely different. He didn’t just look good; he was a grown man, not an immature boy. On top of that, there was something about Thomas that struck a chord with Carina, although she couldn’t really explain it. Perhaps it was that sense of sorrow just beneath the surface. Or the fact that he didn’t really seem to notice her, which merely served to increase her interest.

She knew she didn’t look too bad; she was small and neat and had a dimple in her left cheek that people often mentioned. She usually had all the approval she needed from guys, but Thomas treated her just like everyone else, in spite of the little hints she dropped.

Carina had begun to find herself errands that took her into Thomas’s office. Sometimes she would treat him to a Danish pastry or a piece of cake to go with his morning coffee. She tried to make sure she was sitting close to him when they had a briefing and made every effort to attract his attention. But so far it hadn’t made a bit of difference.

She lingered in the doorway as Thomas studied the report. Her eyes rested on his hand, holding the papers. She thought he had such beautiful fingers, long and slender with attractively shaped nails. From time to time she wondered what it would feel like to be touched by those fingers. Before she fell asleep she would fantasize about his hands, caressing her. How it would feel to lie close by his side, skin on skin.

Completely oblivious to Carina’s thoughts, Thomas was absorbed in the report. It was written in cold, clinical language, with no emotional nuances revealing anything about the man in the descriptions. Short, clipped phrases efficiently summarized the results.

Death by drowning. Water in the lungs. Injuries to the body sustained during the time spent in the sea, as far as they could judge. Several fingers and toes missing. No trace of chemical substances or alcohol in the blood. The old fishing net was made of the same cotton fiber as Swedish fishing nets usually were. The loop of rope around the upper body had been ordinary rope. It appeared that something had been attached to the rope; the end was frayed, and traces of iron indicated that it had been in contact with a metal object.

Nothing in the report indicated that death had been caused by another person.

Suicide or an accident, in that case.

The only strange thing was the rope around the body. Thomas considered this. Why would someone have a rope around his body if he’d drowned accidentally? Had Krister Berggren tried to get out of the water after falling in? Or, if he’d committed suicide, had he made a bungled attempt to hang himself, then regretted it and jumped in instead? In which case, wouldn’t he have removed the rope? Why just push it down his body? Perhaps that kind of question was unimportant given a person’s state of mind just before a suicide attempt.

The fishing net could be explained away as a simple mishap. The body could have drifted into someone’s net and gotten entangled in it. The loop of rope was more difficult to understand. On the other hand, his years as a police officer had taught him that certain things cannot be explained. It didn’t necessarily mean anything.

If the rope hadn’t been there, the death would have been written off as either an accident or suicide right away, but it was chafing Thomas’s thoughts like a tiny stone in his shoe.

He decided to go over to Krister Berggren’s flat. There might be a suicide note or some other information to help explain things.

Krister Berggren had lived on the far side of Bandhagen, a suburb just south of Stockholm.

Thomas parked his car, an eight-year-old Volvo 945, by the curb and looked around. The buildings were typical of the 1950s, made of buff-colored brick, four stories, and no lift. Row after row of blocks of flats met his gaze. There were a few cars parked on the street. An elderly man in a cap was making his way with the help of a walker.

Thomas opened the outer door and walked into the entrance hall. The tenants’ names were listed on a board to the right. Krister Berggren had lived two floors up. Thomas walked quickly up the stairs. On each floor there were three doors made of pale-brown wood, which had become scratched over the years. The walls were painted in a nondescript shade of beige gray.

Beneath the nameplate that said “K. Berggren” was a piece of paper with No Junk Mail written on it in pencil. Despite this, someone had tried to shove a huge bundle of advertisements through the letterbox.

The locksmith had arrived a few minutes earlier; when he opened the door for Thomas, a stale smell immediately surged toward them in a mixture of old food and enclosed air.

Thomas started with the kitchen. On the dish rack stood several empty wine bottles and a dried-up loaf of bread. There were dirty plates in the sink. He opened the old fridge, and the stench of sour milk hit him. Moldy cheese and ham lay next to it. It was obvious nobody had been there for months.

There were no surprises in the living room. A black leather sofa, dreary sea-grass carpet that had clearly been there for some time. On the glass table, various rings left by glasses and bottles bore witness to a predilection for alcohol, coupled with a lack of interest in taking care of the furniture. A few dead potted plants stood on the windowsill. It was obvious that Krister Berggren had lived alone for many years; there was no sign that a woman had shared his life.

The bookcase was crammed with DVDs. Thomas noticed an entire shelf filled with Clint Eastwood films. A few books—some looked as if they might have been inherited, because they had old-fashioned, worn leather spines with gold lettering. On one wall hung a poster showing Formula One cars at the starting grid.

On the table were a pile of assorted catalogs, one copy of Motor Sport, and a TV listings magazine. There was also a brochure for the ferry company Silja Line in the pile. Thomas picked it up and looked at it more closely. Perhaps Krister Berggren had simply fallen overboard from a ferry to Finland. All the big shipping companies passed the western point of Sandhamn at around nine each evening.

He went into the bedroom and looked around. The quilt was pulled over the bed, but there were dirty clothes lying around. An old copy of the evening paper Aftonbladet was on the nightstand. Thomas picked it up and looked at the date: March 27. Could that be the last time Krister was at home? It matched the best-before date on the carton of sour milk in the fridge.

On a bureau stood a black-and-white photograph of a girl with a 1950s hairstyle, wearing a twinset. Thomas picked it up and turned it over. Cecilia—1957, it said in ornate handwriting. The girl was pretty in an old-fashioned way. Pale lipstick, beautiful eyes gazing far into the distance. She had a neat, clean air about her. Presumably she was Krister’s mother. According to the records, she had died at the beginning of the year.

Thomas carried on looking for a suicide note or anything else that might explain the death but found nothing. He went back into the hall and flicked through the pile of mail. Mostly advertisements, a few envelopes that looked like bills. A postcard with a picture of a white beach on the front, and the name Kos covering half the card.

Call me so we can talk! Love, Kicki, it said on the back.

Thomas wondered if Kicki was Kicki Berggren, Krister’s cousin, who was the only living relative they had managed to track down. He had tried to call her earlier on her home number and her cell phone but had only gotten voice mail in both cases.

A quick glance in the bathroom revealed nothing.

The toilet seat had been left up, just as you would expect from a man living on his own. A few dried-up splashes of yellow urine showed up against the white porcelain.

Thomas took a final walk around the flat. He didn’t really know what he’d been expecting. If not a note, then at least something that might show that Krister Berggren had tried to take his own life one cold day in March.

Unless it had been an accident, after all.

![Книга Legendary Moonlight Sculptor [Volume 1][Chapter 1-3] автора Nam Heesung](http://itexts.net/files/books/110/oblozhka-knigi-legendary-moonlight-sculptor-volume-1chapter-1-3-145409.jpg)