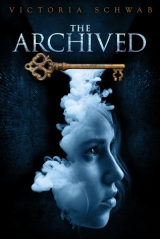

Текст книги "The Archived"

Автор книги: Victoria Schwab

Жанры:

Подростковая литература

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 4 (всего у книги 17 страниц)

SIX

I YAWN AS ROLAND leads me back through the Archive. I’ve been here for hours, and I can tell I’m running out of night. My bones ache from sitting on the floor, but it was worth it for a little time with Ben.

Not Ben, I know. Ben’s shelf.

I roll my shoulders, stiff from leaning so long against the stacks, as we wind back through the corridors and into the atrium. Several Librarians dot the space, busy with ledgers and notepads and even, here and there, open drawers. I wonder if they ever sleep. I look up at the arched stained glass, darker now, as if there were a night beyond. I take a deep breath and am starting to feel better, calmer, when we reach the front desk.

A man with gray hair, black glasses, and a stern mouth behind a goatee is waiting for us. Roland’s music has been shut off.

“Patrick,” I say. Not my favorite Librarian. He’s been here nearly as long as I have, and we rarely see eye to eye.

The moment he catches sight of me, his mouth turns down.

“Miss Bishop,” he scolds. He’s Southern, but he’s tried to obliterate his drawl by being curt, cutting his consonants sharp. “We try to discourage such recurrent disobedience.”

Roland rolls his eyes and claps Patrick on the shoulder.

“She’s not doing any harm.”

Patrick glares at Roland. “She not doing any good, either. I should report her to Agatha.” His gaze swivels to me. “Hear that? I should report you.”

I don’t know who this Agatha is, but I’m fairly certain I don’t want to know.

“Restrictions exist for a reason, Miss Bishop. There are no visiting hours. Keepers do not attend to the Histories here. You are not to enter the stacks without good reason. Are we clear?”

“Of course.”

“Does that mean you will cease this futile and rather tiresome pursuit?”

“Of course not.”

A cough of a laugh escapes from Roland, along with a wink. Patrick sighs and rubs his eyes, and I can’t help but feel a bit victorious. But when he reaches for his notepad, my spirits sink. The last thing I need is a demerit on my record. Roland sees the gesture, too, and brings his hand down lightly on Patrick’s arm.

“On the topic of attending to Histories,” he offers, “don’t you have one to catch, Miss Bishop?”

I know a way out when I see it.

“Indeed,” I say, turning toward the door. I can hear the two men talking in low, tense voices, but I know better than to look back.

I find and return twelve-year-old Thomas Rowell, fresh enough out that he goes without many questions, let alone a fight. Truth be told, I think he is just happy to find someone in the dark halls, as opposed to something. I spend what’s left of the night testing every door in my territory. By the time I finish, the halls—and several spots on the floor—are scribbled over with chalk. Mostly X’s, but here and there a circle. I work my way back to my two numbered doors, and discover a third, across from them, that opens with my key.

Door I leads to the third floor and the painting by the sea. Door II leads to the side of the stairs in the Coronado lobby.

But Door III? It opens only to black. To nothing. So why is it unlocked at all? Curiosity pulls me over the threshold, and I step through into the dark and close the door behind me. The space is quiet and cramped and smells of dust so thick, I taste it when I breathe in. I can reach out and touch walls to my left and right, and my fingers encounter a forest of wooden poles leaning against them. A closet?

As I slide my ring back on and resume my awkward groping in the dark, I feel the scratch of a new name on the list in my pocket. Again? Fatigue is starting to eat into my muscles, drag at my thoughts. The History will have to wait. When I step forward, my shin collides with something hard. I close my eyes to cut off the rising claustrophobia; finally, my hands find the door a few feet in front of me. I sigh with relief and turn the metal handle sharply.

Locked.

I could go back into the Narrows through the door behind me and take a different route, but a question persists: Where am I? I listen closely, but no sound reaches me. Between the dust in this closet and the total lack of anything resembling noise from the opposite side, I think I must be somewhere abandoned.

Da always said there were two ways to get through any locked door: by key or by force. And I don’t have a key, so…I lean back and lift my boot, resting the sole against the wood of the door. Then I slide my shoe left until it butts up against the metal frame of the handle. I withdraw my foot several times, testing to make sure I have a clear shot before I take a breath and kick.

Wood cracks loudly, and the door moves; but it takes a second strike before it swings open, spilling several brooms and a bucket out onto a stone floor. I step over the mess to survey the room and find a sea of sheets. Sheets covering counters and windows and sections of floor, dirty stone peering out from the edges of the fabric. A switch is set into the wall several feet away, and I wade through the sheets until I get near enough to flip the lights.

A dull buzzing fills the space. The light is faint and glaring at the same time, and I cringe and switch it back off. Daylight presses in with a muted glow against the sheets over the windows—it’s later than I thought—and I cross the large space and pull a makeshift curtain down, showering dust and morning light on everything. Beyond the windows is a patio, a set of suspiciously familiar awnings overhead—

“I see you’ve found it!”

I spin to find my parents ducking under a sheet into the room.

“Found what?”

Mom gestures to the space, its dust and sheets and counters and broken broom closet, as if showing me a castle, a kingdom.

“Bishop’s Coffee Shop.”

For a moment, I am genuinely speechless.

“The café sign in the lobby didn’t give it away?” asks Dad.

Maybe if I’d come through the lobby. I am still dazed by the fact that I’ve stepped out of the Narrows and into my mother’s newest pet project, but years of lying have taught me to never look as lost as I feel, so I smile and roll with it.

“Yeah, I had a hunch,” I say, rolling up the window sheet. “I woke up early, so I thought I’d take a look.”

It’s a weak lie, but Mom isn’t even listening. She’s flitting around the space, holding her breath like a kid about to blow out birthday candles as she pulls down sheets. Dad is still looking at me rather intently, eyes panning over my dark clothes and long sleeves, all the pieces that don’t line up.

“So,” I say brightly, because I’ve learned if I can talk louder than he can think, he tends to lose his train of thought, “you think there’s a coffee machine under one of these sheets?”

He brightens. My father needs coffee like other men need food, water, shelter. Between the three classes he’s set to teach in the history department and the ongoing series of essays he’s composing, caffeine ranks way up there on his priority list. I think that’s all it took for Mom to get him to support her dream of owning a café: an invitation from the local university and the guarantee of continuous coffee. Brew it, and they will come.

I try to stifle a yawn.

“You look tired,” he says.

“So do you,” I shoot back, pulling the covers off a piece of equipment that might have once been a grinder. “Hey, look.”

“Mackenzie…” he presses, but I flip the switch and the machinery does in fact grind to life, drowning him out with a horrible sound like it’s eating its own parts, chewing up metal nuts and bolts and gobbling down air. Dad winces, and I turn it off, sounds of mechanic agony echoing through the room, along with a smell like burning toast.

I can’t help glancing back at the cleaning closet, and Mom must have followed my gaze, because she heads straight for it.

“I wonder what happened here,” she says, swinging the door on its broken hinges.

I shrug and head over to an oven, or something like it, and pry the door open. The inside is stale and scorched.

“I was thinking that we should bake some muffins,” says Mom. “‘Welcome’ muffins!” She doesn’t say it like welcome but rather like Welcome! “You know, to let everyone know that we’re here. What do you think, Mac?”

In response, I nudge the oven door, and it swings shut with a bang. Something dislodges and lands with a tinktinktinktink across the stone before rolling up against her shoe.

Her smile doesn’t even falter. It turns my stomach, her sickly-sweet-everything’s-better-than-fine pep. I’ve seen the inside of her mind, and this is all a stupid act. I lost Ben. I shouldn’t have to lose her, too. I want to shake her. I want to say…But I don’t know what to say. I don’t know how to get through to her, how to make her see that she’s making it worse.

So I tell the truth. “I think it’s falling apart.”

She misses my meaning. Or steps around it. “Well then,” she says cheerfully, stooping to fetch the metal bolt, “we’ll just use the apartment oven until we get this one in shape.”

With that she turns on her heel and bobs away. I look around, hoping to find Dad, and with him some measure of sympathy or at least commiseration, but he’s on the patio, staring up at the awnings.

“Chop chop, Mackenzie,” Mom calls through the door. “You know what they say—”

“I’m pretty sure no one says it but you—”

“Up with the sun and just as bright.”

I look out the window at the light and cringe, and follow.

We spend the rest of the morning in the apartment baking Welcome! muffins. Or rather, Dad ducks out to run some errands, and Mom makes muffins while I do my best to look busy. I could really use a few hours of sleep and a shower, but every time I make a move to leave, Mom thinks up something for me to do. While she’s distracted pulling a fresh batch from the oven, I dig the Archive list from my pocket. But when I unfold it, it’s blank.

Relief washes over me before I remember that there should be a name on it. I could swear I felt the scrawl of a new History being added when I was stuck in the café closet. I must have imagined it. Mom sets the tray of muffins on the counter as I refold the paper and tuck it away. She drapes a cloth over them, and out of nowhere I remember Ben standing on his toes to peek beneath the towel and steal a pinch even though it was always too hot and he burned his fingers. It’s like being punched in the chest, and I squeeze my eyes shut until the pain passes.

I beg off baking duty for five minutes just to change clothes—mine smell like Narrows air and Archive stacks and café dust. I pull on jeans and a clean shirt, but my hair refuses to work with me, and I finally dig a yellow bandana out of a suitcase and fashion a headband, trying to hide the mess as best I can. I’m tucking Da’s key beneath my collar when I catch sight of the dark spots on my floor and remember the bloodstained boy.

I kneel down, trying to tune out the clatter of baking trays beyond the door as I slide off my ring and bring my fingertips to the floorboards. The wood hums against my hands as I close my eyes and reach, and—

“Mackenzie!” Mom calls out.

I sigh and blink, pushing up from the floor. I straighten just as Mom knocks briskly on the door. “Have I lost you?”

“I’m coming,” I say, shoving the ring back on as her footsteps fade. I cast one last glance at the floor before I leave. In the kitchen, the muffins are already wrapped in blossoms of cellophane. Mom is filling a basket, chattering about the residents, and that’s when I get an idea.

Da was a Keeper, but he was a detective too, and he used to say you could learn as much by asking people as by reading walls. You get different answers. My room has a story to tell, and as soon as I can get an ounce of privacy, I’ll read it; but in the meantime, what better way to learn about the Coronado than to ask the people in it?

“Hey, Mom,” I say, pushing up my sleeves, “I’m sure you’ve got a ton of work to do. Why don’t you let me deliver those?”

She pauses and looks up. “Really? Would you?” She says it like she’s surprised I’m capable of being nice. Yes, things have been rocky between us, and I’m offering to help because it helps me—but still.

She tucks the last muffin into a basket and nudges it my way.

“Sure thing,” I say, managing a smile, and her resulting one is so genuine that I almost feel bad. Right up until she wraps me in a hug and the high-pitched strings and slamming doors and crackling paper static of her life scratches against my bones. Then I just feel sick.

“Thank you,” she says, tightening her grip. “That’s so sweet.” I can barely hear the words through the grating noise in my head.

“It’s…really…nothing,” I say, trying to picture a wall between us, and failing. “Mom,” I say at last, “I can’t breathe.” And then she laughs and lets go, and I’m left dizzy but free.

“All right, get going,” she says, turning back to her work. I’ve never been so happy to oblige.

I start down the hall and peel the cellophane away from a muffin, hoping Mom hasn’t counted them out as I eat breakfast. The basket swings back and forth from the crook of my arm, each muffin individually wrapped and tagged. BISHOP’S, the tag announces in careful script. A basket of conversation starters.

I focus on the task at hand. The Coronado has seven floors—one lobby and six levels of housing—with six apartments to a floor, A through F. That many rooms, odds are someone knows something.

And maybe someone does, but nobody seems to be home. There’s the flaw in both my mother’s plans and in mine. Late morning on a weekday, and what do you get? A lot of locked doors. I slip out of 3F and head down the hall. 3E and 3D are both quiet, 3C is vacant (according to a small slip of paper stuck to the door), and though I can hear the muffled sounds of life in 3B, nobody answers. After several aggressive knocks on 3A, I’m getting frustrated. I drop muffins on each doorstep and move on.

One floor up, it’s more of the same. I leave the baked goods at 4A, B, and C. But as I’m heading away from 4D, the door swings open.

“Young lady,” comes a voice.

I turn to see a vast woman filling the door frame like bread in a loaf pan, holding the small, cellophaned muffin.

“What is your name? And what is this adorable little treat?” she asks. The muffin looks like an egg, nested in her palm.

“Mackenzie,” I say, stepping forward. “Mackenzie Bishop. My family just moved in to 3F, and we’re renovating the coffee shop on the ground floor.”

“Well, lovely to meet you, Mackenzie,” she says, engulfing my hand with hers. She is made up of low tones and bells and the sound of ripping fabric. “My name is Ms. Angelli.”

“Nice to meet you.” I slide my hand free as politely as possible.

And then I hear it. A sound that makes my skin crawl. A faint meow behind the wall that is Ms. Angelli, just before a clearly desperate cat finds a crack somewhere near the woman’s feet and squeezes through, tumbling out into the hall. I jump back.

“Jezzie,” scorns Ms. Angelli. “Jezzie, come back here.” The cat is small and black, and stands just out of reach, gauging its owner. And then it turns to look at me.

I hate cats.

Or really, I just hate touching them. I hate touching any animal, for that matter. Animals are like people but fifty times worse—all id, no ego; all emotion, no rational thought—which makes them a bomb of sensory input wrapped in fur.

Ms. Angelli frees herself from the doorway and nearly stumbles forward onto Jezzie, who promptly flees toward me. I shrink back, putting the basket of muffins between us.

“Bad kitty,” I growl.

“Oh, she’s a lover, my Jezzie.” Ms. Angelli bends to fetch the cat, which is now pretending to be dead, or is paralyzed by fear, and I get a glimpse of the apartment behind her.

Every inch is covered with antiques. My first thought is, Why would anyone have so much stuff?

“You like old things,” I say.

“Oh, yes,” she says, straightening. “I’m a collector.” Jezzie is now tucked under her arm like a clutch purse. “A bit of an artifact historian,” she says. “And what about you, Mackenzie—do you like old things?”

Like is the wrong word. They’re useful, since they’re more likely to have memories than new things.

“I like the Coronado,” I say. “That counts as an old thing, right?”

“Indeed. A wonderful old place. Been around more than a century, if you can believe it. Full of history, the Coronado.”

“You must know all about it, then.”

Ms. Angelli fidgets. “Ah, a place like this, no one can know everything. Bits and pieces, really, rumors and tales…” She trails off.

“Really?” I brighten. “Anything unusual?” And then, worried my enthusiasm is a little too strong, I add, “My friend is convinced a place like this has to have a few ghosts, skeletons, secrets.”

Ms. Angelli frowns and sets Jezzie back in the apartment, and locks the door.

“I’m sorry,” she says abruptly. “You caught me on my way out. I’ve got an appraisal in the city.”

“Oh,” I fumble. “Well, maybe we could talk more, some other time?”

“Some other time,” she echoes, setting off down the hall at a surprising pace.

I watch her go. She clearly knows something. It never really occurred to me that someone would know and not want to share. Maybe I should stick to reading walls. At least they can’t refuse to answer.

My footsteps echo on the concrete stairs as I ascend to the fifth floor, where not a single person appears to be home. I leave a trail of muffins in my wake. Is this place empty? Or just unfriendly? I’m already reaching for the stairwell door at the other end of the hall when it swings open abruptly and I run straight into a body. I stumble back, steadying myself against the wall, but I’m not fast enough to save the muffins.

I cringe and wait for the sound of the basket tumbling, but it never comes. When I look up, a guy is standing there, the basket safely cradled in his arms. Spiked hair and a slanted smile. My pulse skips.

The third-floor lurker from last night.

“Sorry about that,” he says, passing me the basket. “No harm, no foul?”

“Yeah,” I say, straightening. “Sure.”

He holds out his hand. “Wesley Ayers,” he says, waiting for me to shake.

I’d rather not, but I don’t want to be rude. The basket’s in my right hand, so I hold out my left awkwardly. When he takes it, the sounds rattle in my ears, through my head, deafening. Wesley is made like a rock band, drums and bass and interludes of breaking glass. I try to block out the roar, to push back, but that only makes it worse. And then, instead of shaking my hand, he gives a theatrical bow and brushes his lips against my knuckles, and I can’t breathe. Not in a pleasant, butterflies-and-crushes way. I literally cannot breathe around the shattering sound and the bricklike beat. My cheeks flush hot, and the frown must have made its way onto my face, because he laughs, misreading my discomfort, and lets go, taking all the noise and pressure with him.

“What?” he says. “That’s custom, you know. Right to right, handshake. Left to right, kiss. I thought it was an invitation.”

“No,” I say curtly. “Not exactly.” The world is quiet again, but I’m still thrown off and having trouble hiding it. I shuffle past him toward the stairs, but he turns to face me, his back to the hall.

“Ms. Angelli, in Four D,” he continues. “She always expects a kiss. It’s hard with all the rings she wears.” He holds up his left hand, wiggles his fingers. He’s got a few of his own.

“Wes!” calls a young voice from an open doorway halfway down the hall. A small, strawberry-blond head pops out of 5C. I want to be annoyed that she didn’t answer when I knocked, but I’m still resisting the urge to sit down on the checkered carpet. Wesley makes a point of ignoring her, his attention trained on me. Up close I can confirm that his light brown eyes are ringed with eyeliner.

“What were you doing in the hall last night?” I ask, trying to bury my unease. His expression is blank, so I add, “The third-floor hall. It was late.”

“It wasn’t that late,” he says with a shrug. “Half the cafés in the city were still open.”

“Then why weren’t you in one of them?” I ask.

He smirks. “I like the third floor. It’s so…yellow.”

“Excuse me?”

“It’s yellow.” He reaches out and taps the wallpaper with a painted black nail. “Seventh is purple. Sixth is blue. Fifth”—he gestures around us—“is clearly red.”

I wouldn’t go so far as to say it’s clearly any color.

“Fourth is green,” he continues. “Third is yellow. Like your bandana. Retro. Nice.”

I bring a hand up to my hair. “What’s second?” I ask.

“It’s somewhere between brown and orange. Ghastly.”

I almost laugh. “They all look a bit gray to me.”

“Give it time,” he says. “So, you just move in? Or do you enjoy roaming the halls of apartment buildings, hocking”—he peers into the basket—“baked goods?”

“Wes,” the girl says again, stamping her foot, but he ignores her pointedly, winking at me. The girl’s face reddens, and she disappears into the apartment. A moment later she emerges, weapon in hand.

She sends the book spinning through the air with impressive aim, and I must have blinked, or missed something, because the next minute, Wesley’s hand has come up and the book is resting in it. And he’s still smiling at me.

“Be right there, Jill.”

He brushes the book off and lets it fall to his side while he peers into the muffin basket. “This basket nearly killed me. I feel I deserve compensation.” His hand is already digging through the cellophane, past ribbons and tags.

“Help yourself,” I say. “You live here, then?”

“Can’t say that I do—Oooooh, blueberry.” He lifts a muffin and reads the label. “So you are a Bishop, I presume.”

“Mackenzie Bishop,” I say. “Three F.”

“Nice to meet you, Mackenzie,” he says, tossing the muffin into the air a few times. “What brings you to this crumbling castle?”

“My mother. She’s on a mission to renovate the café.”

“You sound so enthused,” he says.

“It’s just old…” That’s enough sharing, warns a voice in my head.

One dark eyebrow arches. “Afraid of spiders? Dust? Ghosts?”

“No. Those things don’t worry me.” Everything is loud here, like you.

His smile is teasing, but his eyes are sincere. “Then what?”

I’m spared by Jill, who emerges with another book. Part of me wants to see this Wesley try to stave off a second blow while holding a book and a blueberry muffin, but he turns away, conceding.

“All right, all right, I’m coming, brat.” He tosses the first book back to Jill, who fumbles it. And then he casts one last look at me with his crooked smile. “Thanks for the muffin, Mac.” He just met me and he’s already using a nickname. I’d kick his ass, but there’s a slight affection to the way he says it, and for some reason I don’t mind.

“See you around.”

Several moments after the door to 5C has closed, I’m still standing there when the scratch of letters in my pocket brings me to my senses. I head for the stairs and pull the paper from my jeans.

Jackson Lerner. 16.

This History is old enough that I can’t afford to put it off. They slip so much faster the older they get—distress to destruction in a matter of hours; minutes, even. I get back to the third floor, ditching the basket in the stairwell, and pocket my ring as I reach the painting of the sea. I pull the key’s cord over my head, wrapping it several times around my wrist as my eyes adjust to make out the keyhole in the faint wall crack. I slot the key and turn. A hollow click; the door floats to the surface, lined in light, and I head back into the forever night of the Narrows.

I close my eyes and press my fingertips against the nearest wall, reaching until I catch hold of the memories, and behind my eyes the Narrows reappear, bleak and bare and grayer, but the same. Time rolls away beneath my touch, but the memory sits like a picture, unchanging, until the History finally flickers in the frame, blink-and-you-miss-it quick. The first time, I do miss it, and I have to drag time to a stop and turn it forward, breathing out slow, slow, inching frame by frame until I see him. It goes like empty empty empty empty empty empty body empty empty—gotcha. I focus, holding the memory long enough to identify the shape as a teenage boy in a green hoodie—it must be Jackson—and then I nudge the memory forward and watch him walk past from right to left, and turn the first corner. Right.

I blink, the Narrows sharpening around me as I pull back from the wall, and follow Jackson’s path around the corner. Then I start again, repeating the process at each turn until I close the gap, until I’m nearly walking in his wake. Just as I’m reading the fourth or fifth wall, I hear him, not the muddled sounds of the past but the shuffling steps of a body in the now. I abandon the memory and track the sound down the hall, whipping around the corner, where I find myself face-to-face with—

Myself.

Two distorted reflections of my sharp jaw and my yellow bandana pool in the black that’s spreading across the History’s eyes, eating up the color as he slips.

Jackson Lerner stands there staring at me with his head cocked, a mop of messy reddish brown hair falling against his cheeks. Beneath his bright green hoodie, he has that gaunt look boys sometimes get in their teens. Like they’ve been stretched. I take a small step back.

“What the hell’s going on here?” he snaps, hands stuffed into his jeans. “This some kind of fun house or something?”

I keep my tone empty, even. “Not really, no.”

“Well, it blows,” he says, a thin layer of bravado masking the fear in his voice. Fear is dangerous. “I want to get out of here.”

He shifts his weight, as solid as flesh and blood on the stained floor. Well, as solid as flesh, anyway. Histories don’t bleed. He shifts again, restless, and then his blackening eyes drift down to my hand, to the place where my key dangles from the cord wrapped around my wrist. The metal glints.

“You got a key.” Jackson points, gaze following the key’s small, swinging movements. “Why don’t you just let me out? Huh?”

I can hear the change in tone. Fear twists into anger.

“All right.” Da would tell me to stay steady. The Histories will slip; you can’t afford to. I glance around at the nearest doors.

But they all have chalk X’s.

“What are you waiting for?” he growls. “I said, let me out.”

“All right,” I say again, sliding back. “I’ll take you to the right door.”

I steal another step away. He doesn’t move.

“Just open this one,” he says, pointing to the nearest outline, X and all.

“I can’t. We need to find one with a white circle and then—”

“Open the damn door!” he yells, lunging for the key around my wrist. I dodge.

“Jackson,” I snap, and the fact that I know his name causes him to pause. I try a different approach. “You have to tell me where you want to go. These doors all go to different places. Some don’t even open. And some of them do, but the places they lead are very bad.”

The anger written across his face fades into frustration, a crease between his shining eyes, a sadness in his mouth. “I just want to go home.”

“Okay,” I say, letting a small sigh of relief escape. “Let’s go home.”

He hesitates.

“Follow me,” I press. The thought of turning my back on him sends off a slew of warning lights in my head, but the Narrows are too, well, narrow for us to pass through side by side. I turn and walk, searching for a white circle. I catch sight of one near the end of the hall, and pick up my pace, glancing back to make sure Jackson is with me.

He’s not.

He’s stopped, several feet back, and is staring at the keyhole of a door set into the floor. The edge of an X peeks out beneath his shoe.

“Come on, Jackson,” I say. “Don’t you want to go home?”

He toes the keyhole. “You aren’t taking me home,” he says.

“I am.”

He looks up at me, his eyes catching the thin stream of light coming from the keyhole at his feet. “You don’t know where my home is.”

That is, of course, a very good point. “No, I don’t.” A wave of anger washes over his face when I add, “But the doors do.”

I point to the one at his feet. “It’s simple. The X means it’s not your door.” I point to the one just ahead, the filled-in circle drawn on its front. “That one, with the chalk circle. That’s your door. That’s where we’re going.”

Hope flickers in him, and I might feel bad about lying if I had any choice. Jackson catches up, then pushes past me.

“Hurry up,” he says, waiting by the door, running a finger over the chalk as his gaze continues down the hall. I reach out to slide the key into the lock.

“Wait,” he says. “What’s that?”

I look up. He’s pointing at another door, one at the very end of the hall. A white circle has been drawn above the keyhole, large enough to see from here. Damn.

“Jackson—”

He spins on me. “You lied. You’re not taking me home.” He steps forward, and I step back, away from the door.

“I didn’t—”

He doesn’t give me a chance to lie again, but lunges for the key. I twist out of the way, catching his sleeved wrist as he reaches out. I wrench it behind his back, and he yelps, but somehow, by some combination of fighter’s luck and sheer will, twists free. He turns to run, but I catch his shoulder and force him forward, against the wall.

I keep my arm firmly around his throat, pulling back and up with enough force to make him forget that he is six inches taller than I am, and still has two arms and two legs to fight with.

“Jackson,” I say, trying to keep my voice level, “you’re being ridiculous. Any door with a white circle can take you—”

And then I see metal, and jump back just in time, the knife in his hand arcing through the air, fast. This is wrong. Histories never have weapons. Their bodies are searched when they’re shelved. So where did he get it?

I kick up and send him reeling backward. It only buys a moment, but a moment is long enough to get a good look at the blade. It gleams in the dark, well-kept steel as long as my hand, a hole drilled in the grip so it can be spun. It is a lovely weapon. And there is no way it belongs to a punk teen with a worn-out hoodie and a bad attitude.

But whether it’s his, or he stole it, or someone gave it to him—a possibility I don’t even want to consider—it doesn’t change the fact that right now he’s the one holding a knife.

And I’ve got nothing.