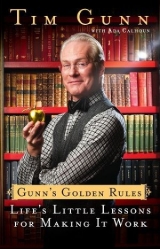

Текст книги "Gunn's Golden Rules"

Автор книги: Tim Gunn

Соавторы: Ada Calhoun

Жанр:

Психология

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 14 страниц)

GUNN’S GOLDEN RULES

GUNN’S GOLDEN RULES

Gallery Books

A Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Copyright © 2010 by Tim Gunn Productions, Inc.

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Gallery Books Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas,

New York, NY 10020.

First Gallery Books hardcover edition September 2010

GALLERY BOOKS and colophon are trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases,

please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales at 1-866-506-1949

or business@simonandschuster.com.

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your

live event. For more information or to book an event contact the

Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com.

Designed by Joy O’Meara

Manufactured in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Gunn, Tim.

Gunn’s golden rules : life’s little lessons for making it work / by Tim Gunn, with Ada Calhoun.

p. cm.

1. Gunn, Tim. Project runway (Television program). 2. Clothing and dress—United States. 3. Life skills—United States. I. Calhoun, Ada.

II. Title.

TT507 .G858 2010 746.9'2092—dc22

2010012417

ISBN 978-1-4391-7656-6

ISBN 978-1-4391-7767-9 (ebook)

Introduction

RULE 1

Make It Work!

RULE 2

The World Owes You … Nothing

RULE 3

Take the High Road

RULE 4

Don’t Abuse Your Power—or Surrender It

RULE 5

Get Inspired If It Kills You

RULE 6

Never Underestimate Karma

RULE 7

Niceties Are Nice

RULE 8

Physical Comfort Is Overrated

RULE 9

Talk to Me:

There’s Always Another Side to the Story

RULE 10

Be a Good Guest or Stay Home

(I Won’t Judge You—I Hate Parties)

RULE 11

Use Technology; Don’t Let It Use You

RULE 12

Don’t Lose Your Sense of Smell

RULE 13

Know What to Get Off Your Chest

and What to Take to the Grave

RULE 14

When in Rome … I Still Wouldn’t Eat

Monkey Brains

RULE 15

When You Need Help, Get It

RULE 16

Take Risks! Playing It Safe Is Never Really Safe

RULE 17

Give Back (but Know Your Limits)

RULE 18

Carry On!

Acknowledgments

GUNN’S GOLDEN RULES

GUNN’S GOLDEN RULES

On Project Runway,I enter the workroom and offer my thoughts—as a mentor, not a judge—on the designers’ work. The advice I give most often is to “make it work.”

That’s not just a catchphrase. It’s a philosophy I’ve followed my whole life, and I credit it with all the wonderful and surprising success I’ve had as a TV personality, teacher, and writer. What “make it work” means is that you should use what you have on hand to transform your situation. It’s always possible to use whatever tools you have at your disposal to create something that you’re proud of and that gets the job done.

Far too often in classes I’ve taught I’ve seen students throw out a lot of hard work and start again from scratch. They may wind up with a good garment, but they aren’t learning the skills that are essential to excelling in a creative field: patience, innovation, and diligence.

I love to see students trying to learn as they go along. The designers and artists I admire spend their whole lives learning. Everything they make may not be a commercial success, but every bit of effort they make gets them closer to realizing their vision.

One of the things I admire about Project Runwayis that it’s really about developing creative design work. I’ll never forget a woman coming up to me at an airport and saying that she loved Runwaybecause she felt it set such a good example for her nine-year-old daughter. “It demonstrates that good qualities of character—like hard work and persistence—pay off, and cheaters never prosper,” she said.

Well, that was one of the nicest things anyone’s ever said to me. I love to think that we’re setting a good example in that way.

Few people remember it now, but Project Runwaywas quite controversial in the beginning. It took the mystique out of the fashion world and said, “This is a demanding, gut-wrenching industry. You need a really strong drive and love for the work in order to be successful.”

I guess we shouldn’t have been shocked, but people in this industry did not react well. They thought we were taking the glamour out of fashion. The design world had been enshrouded in a kind of veil of mystery, and Project Runwaypulled it back to let the world see it for what it was, warts and all. We got some very nasty reviews and some very harsh comments from our colleagues.

But we wanted to tell the truth. And the truth is that in this business, crazy crises happen, like when you’re waiting for the knits to get off the boat from China and the show is tomorrow and the boat doesn’t dock. What do you do? Remove fourteen looks from the show? You make it work, somehow. It’s a fashion 911, and you have to respond to it. You can’t pretend it doesn’t exist.

Now the industry has bought in to the show’s concept completely, and everyone pretends they loved Project Runwayall along. Well, I’m happy that the show’s become so popular and that everyone is so full of praise for it, but I do remember those early days, when we were treated as though we were magicians telling everyone how the rabbit got in the hat.

I like to think that my role in the fashion industry has been a bit like Project Runway’s position among reality shows, which is a voice of simple reason. Let others be shimmery and flashy and brilliant. (And no one loves daring geniuses more than I do.) I will always be there in the wings saying, “You need to be good to people. You need to take your work seriously. You need to have integrity. You need to work with what you’ve got.”

A woman behind me in line at Starbucks the other day introduced herself as an assistant at a popular women’s magazine.

“Are you taking a break?” I asked.

“No, I’m here getting coffee for everyone.” She laughed a bitter laugh and showed me a mile-long list.

“It’s all in the details,” I said. “Do everything one thousand percent. You could be editor in chief some day!”

I’m afraid she thought I was teasing her, but the fact is I am constitutionally incapable of being snarky. I’m not throwing out barbs and making fun of people. I believe in giving a dimension of seriousness to the whole enterprise of creating and talking about clothes, even to red-carpet reportage, and I’m very proud of that.

As anyone who’s been on the red carpet can tell you, the experience is terrifying.You’re always just a hair shy of enduring a humiliating moment or facing someone who’s just there to make fun of you. I thought: I need to be an antidote to all this horrible stuff.

As many people who watch Project Runwayknow, I am a stickler for good manners, and I believe that treating other people well is a lost art. In the workplace, at the dinner table, and walking down the street—we are confronted with choices on how to treat people nearly every waking moment. Over time these choices define who we are and whether we have a lot of friends and allies or none.

So how do we do this social thing well? And by “well,” I mean: How do we become more respectful and further our own goals at the same time? Dear reader, these two concepts are not mutually exclusive; they’re mutually beneficial—and that’s what this book is all about.

To maintain anything like a good working relationship with people, to get by in the world successfully, you need to have good manners. (And you need a sense of humor or you may as well slit your wrists.)

I reflect on manners, or the lack of them, each and every day. There are times when I want to stop the world for a moment and ask certain people some probing questions, such as: All of these people are trying to get off the subway train. Why do you six people think you should enter before we leave? Don’t you realize that if you just clear a path we can get off and you can get on?

In the Internet age, even the very word mannersseems antiquated.

Life moves so rapidly these days that it’s easy to feel justified in being rude.

“I’m rushing home to the babysitter. That’s why I didn’t say ‘thank you’ to the cashier.”

“If I treat my assistant humanely, maybe it will be taken as a sign of weakness and I will lose my job.”

“I get so many e-mails, there’s no time to respond, much less to be eloquent.”

With the advent of certain omnipresent technological devices, with chivalry long gone, with message boards teaching young people that anonymous rudeness is acceptable, we are looking at a great amount of change for the worse.

But let us not be swept up in this tide of rudeness. This book (in addition to being a fun excuse to tell some of my favorite fashion-world stories) is a call to arms, a manifesto for kindness, generosity, and integrity. I hope you will join me in trying to make society a friendlier, more polite, and less aggressive place.

Of course, it’s not like I am perfect. I’ve made many mistakes, and I continue to slip up now and then in my effort to behave well. And you’ll hear all about it!

And yet I always atone for my errors, and there are certain fundamental social protocols I’ve come to hold dear: I don’t believe in texting while dining, sending one-word e-mails in lieu of formal thank-you cards, wearing shorts to the theater, or settling for any of the modern trends that favor comfort over politeness, ease over style.

Being a good friend to other people, being glamorous and attractive, being a success are no accidents. Having a rich career and home life are the result of a great deal of hard work.

But that doesn’t mean the work isn’t fun.

In this book, I will share my thoughts on what constitutes a life well lived. These rules are what I’ve always tried to impart to my students and have tried to follow in my own career and social life. In writing these chapters, I’ve tried to think of you, the readers, as beloved students who have come to me during office hours to ask advice, talk over a dilemma, or just hang out.

Good manners lead to better relationships, more career success, and less personal stress. Manners are a relief, not a terrible obligation. It’s my belief that etiquette isn’t cold and formal; it’s warm and flexible. I am very concerned with manners, but I am not a robot. Manners are simply about asking yourself, What’s the right thing to do?

I deeply believe that if we all have this simple question in our minds, we will do right by one another. We won’t always succeed … As you will learn from this book, in the course of trying to do the right thing, I have let a closet full of unopened gifts pile up in my apartment, overextended myself to the point where I almost had a nervous breakdown, and even put a dear old lady in the hospital!

But I’ve learned from every mistake, and I’m eager for you to learn from them, too. In that spirit, I will be offering my thoughts on manners, reminiscing about my own experiences adhering or failing to measure up to them, and telling what I hope are entertaining stories—not toomany scandalous ones, but I do have a few doozies …

So please, pull up a chair and let’s start our chat!

Make It Work!

AS A LITTLE KID, when confronted with a difficult situation, I would run and hide somewhere in our Washington, D.C., house. I wanted to escape from the world. School, sports, church, birthday parties—anything social terrified me. All I wanted to do was hole up until the event had passed and I could go back to reading alone in my room.

Unfortunately, I couldn’t stay hidden for very long, because the house wasn’t that big and eventually my mother figured out my favorite hiding places. But usually it would be long enough to scare the living daylights out of her, which for me was not an unhappy side effect.

As my mother caught on to each new scheme, I got more creative. I think it was maybe the third or fourth time I hid, I actually ran away outside and found a good secluded spot in the yard. I was thrilled when I heard her inside tearing the house apart. Finally, I had really succeeded in terrorizing her. I could have stayed out in that yard forever.

Well, unfortunately for my escapist fantasies, we had a basset hound, Brandy. My mother sent Brandy out to find me, and she did so immediately.

This made me more determined. I thought: I need to get smarter about this. I need to run awaywith Brandy.

That didn’t work, either, because my parents would yell for me and Brandy would bark back.

Then it became a challenge to run away with her andto keep my hand over her mouth.

The whole project got more and more complicated until, ultimately, I decided it was less trouble just to stay home and be miserable.

In that moment, the seeds of “make it work!” were born. Running away from my problems didn’t help. I had to face up to whatever it was that I didn’t want to deal with—my homework, an angry parent, a fight with a friend—rather than just trying to put it off until it went away. Until you address them, I have since learned, such problems never truly vanish.

I had to make the best of the bad situation. What I found was that if I did that, the situation would rapidly become less bad, whereas if I hid from it or tried to make it go away, I would get more and more anxious and the situation would get worse and worse. I learned very early the wisdom of making it—whatever itwas—work.

The phrase “make it work!” came later, but it didn’t originate on Project Runway. I began using it in my classroom when I was a design teacher at Parsons, the celebrated design college in Manhattan where I worked for twenty-four years. I found it to be an extremely useful mantra when my students were in trouble.

One such example came during a later phase of my academic career. I was teaching Concept Development to seniors. This was a six-hour class that met once a week for the entire academic year—two fifteen-week semesters. It was a long time to work on a single project, and students learned a lot by having to go deep into their own unique concepts.

The year began with the crystallization of each student’s thesis: five to seven head-to-toe looks that represented their point of view as a designer. (It was Joan Kaner, the celebrated style maven and former vice president of Neiman Marcus, who once said to me, “I can tell everything that I need to know about a designer from five looks.” I think about that all the time.)

Those looks were executed in muslin (an unbleached cotton fabric used for prototyping) in a corresponding course that was appropriately called Studio Methods. I would visit that class on a regular basis, especially during fittings, which happened every two weeks.

On the topic of fittings, I forbade my students from designing for themselves or using themselves as fit models for their collection. Why? Because when you wear your own designs, you lose objectivity. It’s important that each designer maintain a well-honed ability to critically analyze his or her own work. If you’re only ever designing for your own body, you’d better be prepared to have a clientele of one.

I like the Project RunwaySeason 7 designer Ping Wu, who famously used herself as a mannequin, as a person even though she’s exhausting to be around. She has so much personality. When I told her at the end of Episode 3, “The workroom won’t be the same without you,” I meant it! I had to talk Jesse LeNoir off a ledge during their team challenge. He’s a lovely guy and quite talented. He recognized many of the problems the judges saw, but he couldn’t convince Ping to fix them.

When we had the auditions, I found her work compelling but her pieces were all hand knits. I said, “How do you translate this to Project Runway? Would you do sewn knits? They won’t have the same Möbius-strip quality.”

In some ways I think she was handicapped by being a hand-knit designer, and by using herself as a dress form. As you may remember, in Episode 2, the model’s rear end was hanging out of her skirt. It was vulgar. Ping’s practice of using herself as a model clouded her objectivity. I think that’s a big part of why she made it only to Episode 3.

One instance in which “make it work!” came in particularly handy was during the spring semester of 2002. One of my students, Emma, was seriously struggling with the silhouette and proportions of the items that made up the looks in her collection. We had three fit models before us, and frankly, the collection was a hot mess.

I was struggling, too, in my efforts to get Emma to see solutions. What exactly was it that was so wrong? Even I couldn’t describe it. The only word that came to mind was everything.She was frustrated to the point of tears when she declared that she was going to throw everything away and begin again from scratch.

“You are not starting over,” I responded. “Besides, even if I agreed that you should, you’ve put twenty-five weeks into this collection, and it will be presented to the thesis jury in a month. It will be impossible to present anything of quality in that short amount of time.” (This was before Project Runway,which would recalibrate my thinking about time!)

“Then what am I going to do?” Emma asked, looking at me helplessly.

“You don’t have time to reconceive your designs, to shop for new fabric, or to make new muslins,” I replied. “You’re going to diagnose the issues with your collection and offer up a prescription for how to fix it. You don’t need to start from scratch! What’s at the core of this is working. The problems have to do with fit and proportion. Do you need to create new patterns? No! You need to take these existing pieces and retool them. You’re going to make it work!”

And she did. Emma’s collection was a success, and she learned so much from seeing it through.

If you look at the process of creating a work of art or a design as a journey of one hundred steps, steps one through ninety-five are relatively easy. It’s the last five that are hard. How do you achieve closure? How do you finish it? That’s the hard part.

MAKING IT WORK MEANS finding a solution to a dilemma, whether it’s a senior-year thesis collection, a difficult boss, or a flat tire. When my students made it work, they reached a new level of understanding about their abilities to successfully problem solve, and that gave them additional resources when moving forward to the next task at hand. When we figure a way out of a tricky situation in our own lives, we learn something and gain confidence in ourselves. Making it work is empowering.

On Project Runway,the phrase serves as a constant reminder of the seriousness of our deadlines and of the finite limitations of each designer’s material resources; in other words, when we return from shopping at Mood, that’s it. Whatever they purchased is what they have to execute the challenge. If they discover that they’re without some critical ingredient, then they’re stuck, and it’s “make-it-work” time.

There’s a big difference between my relationship with my students and my relationship with the Project Runwaydesigners. When my students were in a jam, I could tell them what to do to get out of it. By decree, I cannot tell the Project Runwaydesigners what to do, nor can I assist them in any way other than through words. I learned this the hard way.

During Season 1, Austin Scarlett was having difficulty threading one of the sewing machines. In my then state of naïveté, I sat down at the machine to help. After all the years I’ve spent around designers, I can thread a sewing machine with my eyes closed.

Within seconds, one of the producers called me out of the sewing room.

“What are you doing?” she asked. “You can’t do that.”

“It’s just a sewing machine,” I said. “It will take me one minute to fix.”

“But if you do that for Austin, then all of the other designers will expect you to do it for them,” she said. “And if you don’t, then it may be perceived that Austin had an unfair advantage.”

I hadn’t thought of that. She was right. I had to let go and watch the designers struggle. It took a little while, but eventually I got used to this new role as a hands-off mentor.

But I still enjoy being a hands-on instructor whenever I get the chance. I love how fresh young minds are, and I love watching them grow to take in new information. It’s so satisfying to see them come out the other end of the school year more sophisticated and closer to knowing what they need to know in order to accomplish their goals.

Truth be told, I never dreamed that I would become a career educator. In fact, it’s ironic, because growing up I hated school. And I do mean hated.

Don’t misunderstand me: I loved learning. As a child, I always had a million creative projects going on at home. But I hated the social aspects of school. I was a classic nerd with a terrible stutter. I preferred the sanctuary of my bedroom, and I was crazy about books because they transported me to another time and place (one far less oppressive than Beauvoir, the National Cathedral Elementary School in the 1960s, I can assure you). I was also crazy about making things: I was addicted to my Lincoln Logs, Erector Set, and especially my Legos.

I would spend almost all of my weekly allowance on Legos. And in my youth, Legos weren’t packaged in the prescriptive way they are now; they came as a bunch of anonymous blocks that you would purchase according to size and color, plus doors, windows, and, later—be still my beating heart—roof tiles.

As you can probably imagine, between my stutter and my fetishizing of Lego textures, at school I was taunted and teased. I knew that I wasn’t one of the cool kids, and I never tried to pretend otherwise. I was always the last kid picked for games at recess. (Perhaps it’s no wonder that I hate, loathe, and despise team sports even to this day.)

My big macho FBI-agent father, George William Gunn, was J. Edgar Hoover’s ghostwriter, and he not entirely happy about the oddness of his only son. He coached the Little League team and did everything he could to get me on a sports field. It was a disaster. I was bullied. I was beaten up.

Looking back, it seems like having a tough-guy father would have been helpful, but the truth was, he really never seemed to understand me, so we never had much of a relationship. And oddly enough, even when he knew I was getting pummeled at school, he didn’t teach me how to fight back. He never once said, “Let me show you how to sock someone.”

The result was that I was a terrible fighter. I thought I was going to be a concert pianist (yes, I was every kind of nerd), so I would not hit for fear of breaking a hand. That meant I was a biter and a hair puller. If you got into a tangle with me, that’s what would happen. You’d get bitten and have your hair pulled. I wouldn’t even know what I was biting. I would just be in a frenzy, biting anything I could get a hold of.

An interviewer once asked me, “Who would win in a fight, you or Michael Kors?”

“Oh, that’s easy: Michael Kors,” I said. “Because I’m a hair puller, and he barely has any hair. There’s not enough to hold on to.”

When I was older and had to declare a sport, it was swimming. I loved swimming primarily because it’s solitary—that and you don’t sweat. (My sense of propriety was off the charts even back then.) Furthermore, I was good at it, especially the breaststroke and backstroke. In an unexpected and extremely appreciated show of support, my father took up coaching the swim team.

So I had swimming and my grades to be proud of. I also had the piano, which I studied for twelve years and became quite good at, but there was no reason to share that tease-worthy tidbit with my classmates. And yet, I was flailing. What was I going to be truly good at? What would it take to prove to my peers that I did in fact have value other than as a punching bag? For a long time I had no idea.

My teaching career began in an innocent enough way. When I was twenty-five years old, a former and much beloved teacher, Rona Slade, invited me to be her teaching assistant for a summer course for high school students at the Corcoran School of Art (now the Corcoran College of Art), one of the nation’s last remaining museum schools and my alma mater (class of ’76).

They really care about craft there. The Pre-College Intensive Workshop met six hours a day, five days a week, for a month. Rona and I had a great time and played off each other well. I felt proud that I could help someone for whom I had so much respect.

At that point I was a financially strapped sculptor who made ends meet by building models for architecture firms in Washington. Although I enjoyed model making, it wasn’t very lucrative when one factored in the vast amount of time required to make each model. I was probably making about a dollar an hour.

But I loved sculpture. One of my favorite artists is the sculptor Anne Truitt. When I first saw her work in 1974, I was transformed. It was like the first time I saw a painting by the abstract expressionist Mark Rothko. I felt physically lifted off the ground. I’ve always thought the reason Truitt wasn’t as well known as she deserves to be is that she doesn’t easily fit into any particular genre—neither in the Washington Color School nor the Minimalists. There’s not a box to put her in, so she gets lost. I was so lucky later to study under her and then to speak at the opening of her posthumous retrospective at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in 2009.

In any case, when Rona asked me to stay on at the end of the summer of 1978 to work at the college, I jumped at the chance. The position would include teaching a three-dimensional design course as part of the first year of studies. Furthermore, it was full-time, which meant that it came with benefits. Even better, it paid a whopping $6,000 per academic year. Needless to say, I was ecstatic.

But then, when it got closer to my start date, I was terrified.

I realized I had no idea how I would fare in the classroom without Rona at my side. Would I be teased as I had been in grade school? Would the students throw paper planes and spitballs? Would they tie me up and hurl me out the window and into the parking lot? The more I thought about it, the more gothic the scenarios became, and the more I was struck mute and paralytic with terror.

Attempting to drive to work on that first day, I found that I was incapable of pushing down on the accelerator. I sat for a good ten minutes or so before I rallied sufficiently to get the car to move. When I arrived in the school’s parking lot, directly across the street from the White House, I got out of the car and … promptly threw up on the asphalt.

Ah, the dawn of a glorious career,I thought, vomiting in front of my new place of employment.

I washed up and walked dizzily into my classroom to greet my new students. I found that the only way that I could appear to be even remotely composed before them was to stand with my back braced against the blackboard, because my knees were shaking so badly that I knew I would topple over without the wall’s support.

I would like to tell you that the next day was better and that the day after that was better still, but that would be a lie. This same horrible scenario of fear and sickness was repeated for several days in a row.

Finally, I gathered up enough courage to share my terror with Rona. I was sure she would tell me I should quit immediately. But instead, she said very matter-of-factly with her Welsh accent, “Oh, I’m familiar with this malady. It will either kill you or cure you. I’m counting on the latter.” And she smiled tenderly, my very own Florence Nightingale!

Indeed, it cured me—eventually—and I was able to make it through the year without dying or passing out in front of my class. And the students didn’t throw airplanes or hurl me out the window. From then on, I was even able to keep down my breakfast. Talk about make it work!

I’m not built to be a public persona, but through sheer force of will, I’ve made myself step up to the plate. I’m really fortunate. I had parents who believed in education and a mother in particular who nurtured and fostered culture in our home. She wanted her children exposed to as much as possible. We went to museums all the time. We read books. I wasn’t born with a silver spoon in my mouth, but I was extremely lucky, because in our home education and exposure to culture were everything. Either one can help you through life.

Everything got better when I became a teacher. I found an apartment and moved out of my parents’ house. I was part of a new community and made new friends.

The only sad thing was giving up my sculpture studio, which I’d long shared with the painter and my dear friend Molly Van Nice. In fact, I gave up sculpture altogether. I thought I was going to miss it, but I found that the teaching experience was creative in its own way. It was so thoroughly satisfying and rewarding that I no longer felt the need to make my own artwork.

Within the hallowed walls of the distinguished institution in which I worked, it was the precedent that one practiced what one taught. Rona did not. She had been a textile artist, but she was no longer engaged in that work. I decided to embrace her as my role model, and even though my not being a practicing artist or designer raised some eyebrows, I thought: I’m not apologizing for this. And I’m not pretending that I’m doing something that I’m not. Besides, I can always return to sculpting if I hear the call. It’s not going anywhere.

One spectacular experience from my time teaching at the Corcoran was a classic “make-it-work” moment. In late October 1979, the school received a call from the White House requesting that our students make original ornaments for the Christmas tree in the Blue Room. The president at the time was Jimmy Carter.

My reaction: How exciting! The catch was that we had a mere week to create everything, because whoever had made an earlier commitment had backed out, or perhaps had made something horrible and unacceptable. (We heard a rumor that the Jimmy Carter White House perceived the work of this original ornament maker to be “inappropriate,” and we had a wonderful time trying to imagine what in the world those ornaments had looked like.)