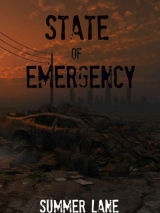

Текст книги "State of Emergency"

Автор книги: Summer Lane

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 14 страниц)

Summer Lane

STATE OF EMERGENCY

For Mom & Dad.

Thanks for believing that writing is a “real” job.

Prologue

I don’t know how it happened. Nobody does. There are only theories, empty rhetoric and doomsday prophecies. None of them are right, but none of them are completely wrong, either. They all have a grain of truth. All I know is where I was and what I was doing when it happened.

The day had started out like every other day of my life. I hit the snooze button on my alarm about five times before dragging myself out of bed. I combed back my unruly red hair, threw on some clothes, and went into the kitchen. As usual, my dad hadn’t gone to the grocery store, so breakfast consisted of burnt toast and a teaspoon of olive oil.

Because fatty acids are supposed to be healthy for you.

And because there’s nothing else to eat in my house except a can of string beans from 1999.

Being nineteen, graduated from high school and unemployed, I didn’t have much to do besides surf the internet looking for interesting stories and reading my stack of books from the library. Lately I had applied for a multitude of different jobs, including a flight attendant, car washer and hotel manager. Needless to say, none of those positions panned out for me.

I’m more of the independent type, getting paid by my dad to help him out with his job as a Los Angeles detective. He’s been letting me poke around in his cases since I was a freshman in high school. I’m good at it, too. Criminal justice, that is. I even wanted a degree in it, but since I’m flat busted broke and stuck in a two-bedroom home with an empty refrigerator, my options are kind of slim.

Anyway, after I looked for a few jobs online, I closed my laptop and started cleaning the house systematically. My dad and I lived in a small house in the middle of the outer suburbs of Los Angeles. Culver City, to be exact. It’s about ten minutes away from Hollywood. The land of spray-on tans and yoga classes.

It’s a nice place to live as long as you don’t drive about five miles in the opposite direction. In that case you’ll end up in the middle of a ghetto. A visit to the grocery store might end up becoming a drive-by shooting.

Unsurprisingly, I’m an introvert.

So that day, that regular, average day, turned out to be a day that not only changed my life – but everybody else’s.

It was the day technology turned on us.

It was the beginning of a major pain in the butt.

Chapter One

It’s exactly 6:32 p.m. on December 10th. I know, because I’m texting my dad, telling him that I’m going to bring home Chinese takeout for dinner when the screen goes dead.

I’m talking died.

The battery gets hot in my hand and the digital clock in my car disappears. I am idling on the side of a busy curb in Culver City. I pop the battery out of my phone and put it back in, getting zero results.

And that’s when I notice that the car is silent. Off. Nada.

I turn the key a few times in the ignition but I can’t get anything from the engine. It won’t even try to turn over. Freaked, I look out my window. Unfortunately for me, that doesn’t do anything to ease my conscience. Every streetlight, lamp, apartment window and neon bar sign shuts off simultaneously.

I watch as an entire boulevard of cars die. Headlights disappear, engines cut out and there are vehicles crashing and smashing against everything in sight. Somebody screams. It’s probably me, but I’m not cool with admitting something like that.

I crawl out of my car and stand on the sidewalk. Everybody is reaching for their cellphones, looking to call 9-1-1. But it’s a no-go. Everybody else’s phones are dead, too.

That isn’t the worst of it.

I turn. Los Angeles is clearly visible in the distance, its signature round skyscraper lit up like a Christmas tree. I have a brief feeling of comfort knowing that the electricity is still on over there. Emphasis on brief. The tower goes black, as does the rest of the city, and just like that the entire region is plummeted into complete, utter darkness.

People are relatively calm at first. I mean, power outages do happen. But cars dying? Cell phones melting? Digital watches flickering out?

What kind of a freak thing is that?

I have an idea, but I didn’t want to voice it out loud. I’m smart enough to know that a panicked crowd can turn into a mob pretty quickly so I keep my big mouth shut and remain on the sidewalk. Motionless. Cautious. Wondering how I’m going to get home when a sea of unmoving cars stretches from here to the city limits – if not farther. It’s been a good twenty minutes since everything died and I’m getting worried. Any cop or ambulance should have been here in ten minutes.

Are their cars dead, too?

What about traffic helicopters? Those babies are always hovering over LA, doing regular traffic checkups. Instead it’s like everything is silent. Like a graveyard of cars and the unlit buildings are headstones.

I’ve got to stop reading horror novels, I think.

As confusion rises, people get out of their cars and start walking around. One lady starts crying, unable to get her cellphone to work or her car to start.

Welcome to the club, sister.

I don’t notice anybody injured but…suddenly I hear a distant humming sound. I strain to tell what it is, wondering if it’s the cavalry finally on its way. It’s about time. But it doesn’t get any louder, just closer. Like wind whistling through an empty tunnel. I search the skies for a helicopter or something, coming up short.

Everybody else is doing the same thing, some of them wigging out a little more than necessary. That is, until it hits. I feel the ground shake underneath me as a hulking mass streaks above our heads, barely visible against the night sky.

I am so shocked, so terrified, that I can’t even move. I just watch in horror as a plane descends like a missile a few miles past the city, hitting the ground. The impact is unbelievable. It’s like having a meteor or a bomb hit the guy standing next to you. I am thrown off my feet and yes, my eardrums start to ring.

A mammoth volley of flames erupts in the distance.

It lights up the dark city like a bonfire. I can feel the heat on my face all the way from here. People start screaming. Los Angeles International Airport isn’t too far away. If the airplanes are dying, it could be a long night of falling stars.

I scramble to my feet, my terror palpable, turning my mouth cotton dry. I don’t know what’s happening but I do know this: I have to get off the streets.

I wrap the strap of my body purse around my wrist a few times and stumble forward several steps, my head still ringing from the distant explosion. People are doing the same thing everywhere, shuffling around like a bunch of zombies. It’s kind of creepy, actually. Everything is bathed in a dull orange light. People arestarting to look more than a little terrified at this point. Panicked.

To keep myself from losing it, I count to one hundred over and over as I walk down the streets, moving with purpose. I move as fast as I can, breaking into a sprint as I round the corner. The street here goes underneath the 405, LA’s busiest freeway. There are people standing on the edges of the overpass, pointing and yelling, looking at the airplane in the distance.

By now I’m breathing hard. I keep moving under the freeway, running along the sidewalk. People are climbing out of their cars. Some guy wearing baggy pants and a backwards baseball cap steps onto the road.

“What’s going on, man?” he asks somebody next to him.

“I don’t know. I don’t understand…” the stranger replies, fear in his eyes.

I concentrate on walking, avoiding eye contact, just one thing on my mind: Get home. Get home and find dad.

Home is about three miles from here. I can make it if I move quickly. When emergency vehicles get here the streets will be blocked and locked for hours. I need to squeeze through now.

“Oh, my god!” A woman in a beanie exclaims. “It’s another one!”

I turn around, watching as another airplane descends dangerously low over the city. The same screeching, ripping sound fills the air. Despite my ringing eardrums I can feel it. I break out into a dead run.

A few beats later another airplane strikes the ground. The impact isn’t as intense as the first one because it’s further away. It still shakes the ground and sends a shockwave across the city. I stagger a little bit, feeling like a seasick sailor stumbling around on the deck of a ship.

“Come on…” I mutter, looking at my cell phone again. It’s still dead, and every Google-ready solution to turning on a dead phone isn’t working. I stuff it back in my pocket, delving onto a side street off the main boulevard. People are coming out of their apartments, restaurants and nail salons. The air is crisp and cold, burning my throat with every breath.

And every block it’s the same. Lights are off, cars are frozen on the streets, people are forming into crowds, looking to the skies as another plane passes over the city. Streets are becoming gridlocked, panicked people who don’t know how to escape whatever’s happening.

I just avoid them. Avoid the busier streets, the gridlocks, the people starting to panic. I manage to turn over a three-mile walk in less than an hour despite the crowds.

By the time I reach my neighborhood the entire city is bathed in white noise: The sound of people yelling, calling for help and things blowing up. My street is totally dark. Usually I can see the cheery facades of the old houses lit up from the inside by residents that have been here since the 1950s. Not tonight. Tonight everything is dark.

I start jogging until I reach our house. It’s blue and white with a little garden of flowers in the front yard. I take the keys out of my purse with shaking hands, jam it into the lock and open the front door. I slam it shut behind me.

“Candles, candles,” I say aloud, feeling my way into the kitchen. I open the cupboard under the sink and pull out some emergency candles. I light the wicks with some matches hidden the utensil drawer, illuminating the dull yellow paint on the walls. I flick the light switches, try the TV, mess with the radio. Nothing, nothing, nothing.

Okay, what do I do? The power is out. The cellphones are dead. The cars are busted. The airplanes are falling out of the sky. Things aren’t exactly looking rosy.

I stop and sit on the couch, holding my head in my hands in the dark.

“Breathe in, breathe out,” I say. “Don’t panic.”

I think about all the conversations I’ve had with my dad about emergency protocol. As a cop, he’s seen plenty of people in high-stress situations. It always pays to be ready, he told me. Most people are unprepared for an emergency, so they get scared and start raiding grocery stores for food and water when a crisis hits. They’ll start breaking into houses and acting like wild savages.

One minute, civilized. The next? A bunch of psycho rioters.

I get up, common sense hitting me in the head like a hammer. I take a candle to my bedroom and open up the closet. I have a go-bag inside, compliments of my father’s insistence that I have an emergency plan in the event of a nuclear attack. Or in this case, a random power outage and malfunctioning technology.

I grab the backpack and run around the room like hyper dog, grabbing things like a photo album, a stuffed animal from when I was nine, and a warmer coat. I drag the stuff into the living room and throw open the hall closet.

Boom.

A powerful impact shakes the house. I grab the wall to keep from falling over, horrified as a blast of orange light ignites about three miles away from my house. Another airplane. They’re falling faster, now.

I can’t stay here. I can’t wait for dad. I have to get out.

Calm, calm, calm, I repeat internally. Don’t panic. I got this.

I pull a smaller bag from the closet and throw it on the couch, unzipping it as fast as I can. There are two weapons inside. A semi-automatic and my grandpa’s cowboy pistol. I take the semi-auto and strap the holster around my waist, hiding it under my jacket. I know my father is already armed wherever he is, so I put Grandpa’s pistol into my backpack and dump all of the ammo into the side pocket.

Don’t panic, don’t panic.

That’s my mantra.

I zip everything up, toss in some candles and lace up my combat-style boots. I bought them this year because I thought they’d look trendy. Now I’m glad I have them because they’re going to be practical.

The radio!

I suddenly remember our emergency radio. I slide into the kitchen and open one of the shallow drawers. In the back there is a small, metallic box. I pop it open and take the radio out. A satisfied smile crosses my face for a brief moment. The box is made out of ferrite, a type of metal resistant to technological attacks, or as my dad would say, “e-bombs.”

I wind up the radio for a few minutes and turn it on. At first there is no sound, only static. And then I turn it to another station, and another, and another. Because every single one is all saying the same thing.

“If you can hear this, this is not a drill. Stay inside and seek shelter. If you are not in your homes, find shelter immediately…”

My blood runs ice cold as I shut the stupid thing off and shove it into my coat pocket. The only piece of technology is the house that’s working is the radio: The one thing that was protected in the ferrite case. I grab the backpack, take one last look at the house and head towards the back door.

Once outside, I pause and listen. Usually right now is about the time you would hear sirens or helicopters or bullhorns telling people to shut up and let the emergency workers do their job.

Instead I’m still just hearing the sound of unorganized panic.

Shuddering, I head to towards the alley, where my dad and I built a little garage. I open it up and step inside, using the flashlight to navigate through the piles of tools and machinery.

And I look at my escape vehicle.

It’s a 78 Mustang dad and I worked on together. While I’m not an automobile expert by any stretch, I do know that this baby should run as long as I have gasoline in the tank. My dad and I installed ferrite cores, a protective cage made out of the same metal that was keeping the radio safe in the kitchen drawer. Its main purpose is to guard a piece of technology from an electromagnetic pulse – which is what I think just wiped out every piece of computer-based technology in Los Angeles. Because that’s what an EMP does. It kills computers.My Mustang doesn’t use a computer chip to start up, unlike most of the cars on the road. It should be unaffected.

To think that my dad’s casual hobby of emergency prepping would come in handy. How did that happen?

I throw my backpack in the passenger seat and check the trunk. There are a few sealed canisters of gasoline, a box of tools with replacement parts for the truck and three cases of bottled water.

Always be prepared, my dad used to say.

Why do parents always have to know everything?

I slam the trunk shut and get in the driver’s seat.

“Please start,” I pray. “Please, please, please…”

I turn the key in the ignition. It feels like a million years go by before the engine turns over and it rumbles to life, smelling like gas.

I never thought I’d think gas smelled wonderful, but I do right now.

I open the garage door and back up, coasting into the alley. I keep my headlights off, not wanting to draw attention to the fact that I’m probably the only person in the city with a working car. That could be seriously dangerous.

I hit the road and step on the gas, doing sixty on the boulevard. As I get closer to the more populated areas I have to avoid stopped cars on the road. People perk up and start pointing and yelling when my car roars by. It makes me nervous. Way nervous. I’ve seen War of the Worlds before.

“Okay, dad,” I say, holding the steering wheel with a death grip. “I know where to find you. You’d better know where to find me.”

Chapter Two

I had a pretty normal family. My mom was the manager of a chain hotel in Culver City, which meant her work was about five minutes from our house. She would spend all her time there, only coming home to eat, drink and sleep.

Oh, and occasionally speak to me.

I didn’t see her very much. My dad was a Los Angeles cop, so he kept weird hours, too. He worked at night and slept during the day, which meant that the curtains in our house were pretty much closed all the time.

As for myself? My mom wanted to send me to some fancy boarding school in Europe, but of course my parents couldn’t afford that, so her dream of dumping me off in a foreign country was canned. My dad was more old fashioned in his thinking. He wanted me to be at home more often, so he enrolled me in a charter school program. I only had to go to a class three times a week, while all my other homework was done at home.

I loved that setup. I was a shy kid. Terrified of my own shadow, as my dad would always tell me. I hung out at home most of the time, seeing my parents only in glimpses. I didn’t have any friends. It just wasn’t my thing.

When I was eight years old, my parents divorced. It didn’t affect me in the way you would think it would. I never saw my parents together anyway, so it was just like having one of them permanently gone. Big whoop. Fortunately, my boarding-home-crazed mother didn’t win custody of me. I got to stay with my dad.

I only visited my mother three times a year, despite the fact that she worked only five minutes away from our house. I think it was because I was angry with her for trying to get rid of me for so many years. I just didn’t want to see her.

My dad, Frank Hart, had been in the military for a few years before he decided to become a cop. He entered the academy when he was twenty-five. He was on the Los Angeles force for thirty years before he decided to become a private detective. Now he helps sniff out terrorists in buildings and give advice to young guys who don’t know one end of their guns from the other.

I loved my dad. I love him now.

I didn’t get to see him very much, but the difference between his love and my mother’s love for me was worlds apart. Mom wanted to dump my butt in France. Dad wanted me to stay home because he said he’d miss me.

My dad was also one of those people that believed a national emergency could happen at any second. He’d dealt with the Los Angeles riots during the 90s and seen all kinds of crazy crap as a cop. Murders, abuse, suicides. He was the kind of person that hoped for the best but expected the worst. His belief that bad things could happen at any moment turned into a hobby that I was more than happy to humor him about – anything to make him forget to make me do my algebra homework.

Which is why we have go-bags in every room of the house and a pre-planned rendezvous point. It’s all suddenly becoming an outstanding idea, given the fact that my dad’s paranoid prophecy about Los Angeles becoming the immediate site of Armageddon is coming true. I can’t believe it’s even happening.

I am racing down a little-known back road in Los Angeles, curving around the city and away from the freeway.

“If there’s ever a crisis in Los Angeles, like a natural disaster or a terrorist attack,” my dad had told me, “we need to count on the fact that the Internet and cell towers will go down. There won’t be any electricity, so if we get separated we have to know where to rendezvous.”

In retrospect, my dad is a genius. The two of us own a little cabin in the Sierra Nevada mountains, not too far away from Kings Canyon National Park. It’s beautiful, secluded and supplied with emergency goodies. Our plan was that if we ever got separated for some reason, we would meet at the cabin. And now, with the entire city swarming like ants escaping a flooded anthill, it was the wisest decision we ever made.

As I drive I keep my headlights on only when I am far enough away from heavily populated areas. This road is windy. Definitely the long way out of the city, but I don’t want to risk getting stuck in a panicked mob.

“Give me something,” I say out loud, turning the crank radio up to full volume. Only bits and pieces of an emergency broadcast will come through. All I can catch are words, like “electromagnetic pulse,” “seek shelter,” and “terrorist attack.” Those words send a chill up my spine, making me wonder who and what is behind such a devastating attack on Los Angeles. And were we the only ones that were hit?

I take a few calming breaths. An anxiety attack behind the wheel of a moving vehicle would probably be detrimental to my health, so I concentrate on navigating the winding, empty road. I keep looking out my windows, paranoid that an airplane is going to drop on my head and turn me into a barbeque appetizer.

I scream.

Somebody is standing in the middle of the two-lane highway. It’s a man. He’s perfectly still, looking directly into my headlights like I’m an oncoming mosquito rather than a moving mass of metal going eighty miles per hour.

I slam on the brakes and my car screeches, smelling like burning rubber. I turn the steering wheel in an attempt to swerve out of the lane, barely missing him by a foot or two. My car starts to skid, then drift, then turn in a full circle. I take my foot off the brake and I’m thrown forward against my airbag-lacking steering wheel. The car screeches to a halt, throwing puffs of smoke into the air.

Panting for breath, trying to get my senses together, I look out the window. The man is moving towards my car. Quickly. I panic throw the car in reverse, hitting the gas. But, because I suck at backwards navigation, I shift back to drive. The man starts waving his hands back and forth.

“Wait!” he says. “I’m a soldier!”

At the word soldier I hesitate for a moment. He’s wearing jeans, but no uniform. Just a green tee shirt. I can’t see his face, but his hair is overgrown, drawn back in a ponytail. There’s no way he’s active duty military.

And then I see the blood.

His shirt is stained with it, crusting over on the sleeve. I suck in my breath, horrified, and open the door without thinking. See, I’m a pansy when it comes to helping people. When I was little I used to run up to stray cats and put them in a box to take to the animal shelter. When I was in high school I used to run up to stray people and give them money or clothes or shoes. Whatever they needed.

It’s my weakness as much as it is my strength.

“What happened?” I ask, stepping out, keeping the engine running. It’s freezing outside, 11:30 p.m. We’re alone on the back roads of some lesser-known Hollywood hills. “Oh, god…how bad are you hurt?”

Wary, I keep my distance, sliding my hand underneath my coat for the semi-automatic. I have no desire to use it – and don’t ever plan on it – but it gives me some confidence that I have something to defend myself with.

“Easy,” he says, lifting up his hands. “I’m not going to hurt you.”

“Prove it.”

He wiggles his fingers, which are covered in blood, too.

“I just need a ride,” he says. “If you’re headed north.”

“I didn’t stop to give you a ride,” I reply, opening the door to the backseat. “I stopped to see if I could help you with all that blood.”

I rifle through my backpack and pull out a first aid kit. He watches me without moving, still halfway encased in the glare and shadows of the headlights.

“You got a name or what?” I ask.

“You tell me yours and I’ll tell you mine.”

I smirk. “Clever.” I wave him over, keeping my fingers ready to grab my weapon at any moment. So I can, like, wave it in his face to seem intimidating. “What happened to you?”

He walks over. His body is tensed up, but from pain or stress I can’t tell. Closer to me I inhale, noting how tall he is. He’s also very ripped. Not that I care, but facts are facts. His face is handsome, lined with a thin beard that would accentuate his long hair nicely if it weren’t smudged with sweat and grease.

“Long story,” he grunts. “I can do this.”

“It’s my stuff. I’ll do it,” I snap. “Where?”

He pulls the sleeve of his shirt up, revealing a muscular arm with a painful injury. It’s crusted over with dried blood.

“What is that?” I ask, feeling squeamish.

“Glass.”

“How…?”

“Car accident. Five miles back.” He sighs heavily. “Whenever everything went out. I got slammed into a pickup.”

“You might have a concussion.” I have to stand on my tiptoes to flush the wound out with a bottle of water It’s not bleeding too badly – nothing that will kill him, anyway. A rush of heat bolts up my arm when our hands accidentally touch. I draw back instantly, embarrassed. He doesn’t seem to notice. “Have you seen the city?” I ask.

“Part of it.” A muscle ticks in his jaw. “You?”

“I was there.” I swallow, getting shaky thinking about the crap that went down. “There were airplanes falling out of the sky. Everything died at the same time. People were everywhere…” I trail off, not wanting to sound like I’m a complete nervous wreck. “They’re evacuating everybody.”

“Yeah, but without cars people won’t be going anywhere.”

I bite my lip.

“I know.”

I take tweezers and start pulling little shards of glass out of his skin. It’s seriously the grossest thing I’ve ever done. Plus, the fact that my hands are shaking doesn’t help matters.

The man gently takes my wrist and holds it for a second, shifting his position. He looks right at my face, giving me the once-over from head to toe. I blush, flustered, but don’t move.

“How old are you?” he asks. “Where’s your family?”

“I’m old enough,” I reply, slipping out of his grasp. “Let me wrap that for you.”

I take out my medical tape, dry the wound and wrap it up.

He stands there, silent.

“You’re alone,” he states gravely.

“What’s it to you?” My hand inches back towards my gun.

Noticing my anxiety, he makes an effort to relax his stance.

“I’m just trying to help,” he says. “I’m a Navy Seal. I’m not a bad guy.”

“Sounds like something a bad guy would say,” I snort.

“I’m going to be straight with you. I need a ride.”

“My dad told me never to talk to strangers, much less give them rides.” I shut the back door. “I shouldn’t have even stopped.”

“But you did.” The corners of his mouth curve upward. “Thank you.”

I pause, sitting down on the driver’s seat. One leg in, one leg out.

“You’re welcome.” I place my hand on the door. “And you’re not an active duty Navy Seal. Your hair is way too long.”

“I’m a former Seal,” he shrugs.

“So you lied,” I mutter.

“No, I didn’t. Listen, I can pay you for a ride, if that’s what you want,” he says.

“I don’t want money.”

“Look,” he says. “I just need to get to Squaw Valley. It’s just outside of Sequoia National Park.”

I close my eyes, ticked.

Of course.

Squaw Valley is in the foothills, about forty miles below our emergency cabin.

“What’s your name?” I ask again.

“Chris,” he says. “Chris Young.”

I exhale dramatically, blowing my bangs out of my eyes.

“I can take you,” I reply. “But if you try anything, I’ll shoot you right between the eyes. Seriously.”

He almost smiles.

“Yes, ma’am.”

I nod. “Get in. I’m wasting gas.”

“Let me get my gear.” He walks over to the side of the road and grabs a backpack and jacket, coming around to the passenger side. It’s a military-issue backpack, his jacket is leather, though.

“What are you, a biker?” I ask.

“Was,” he says.

“The pulse got your bike?”

“Totaled it.”

“You’re lucky you’re alive, you know that?”

He flashes a brilliant smile.

“I know.”

I clear my throat and press down on the accelerator, eager to get the heck out of here. Chris’s presence in my car puts me on edge, reminding me for the millionth time that my dad has warned me repeatedly over the course of my young life never to talk to strangers and never get in a car with one.

Well, guess what? The world has turned into a freaking Armageddon and I’m going to do what I want. Besides, Chris might come in handy. He’s a military guy. Tough, by the looks of it. This could be a positive thing.

“So what’s your name?” he asks, totally relaxed against the seat.

His voice is deep. Just the hint of a southern accent. “Or are you going to tell me?”

“Cassidy,” I say. “You can call me Cassie, though.”

“Alright, Cassie,” he replies, serious. “What’s a kid like you doing with a vintage piece of work like this?”

“You mean my car?”

“No, I mean your boots.”

“Shut up.” I find myself smiling. “It’s my dad’s. I mean, it’s both of ours.”

Silence.

I turn up the radio, discouraged when nothing but static comes through yet again. “Where are you from?” I ask at last.

“San Diego.”

“What were you doing in Los Angeles?”

“Weekend bike ride.” He looks sideways at me. “And you?”

“I live in Culver City,” I shrug.

“Where are your parents?”

“Seriously? Do I really look that young?” I press down on the accelerator a little more, giving into my unconscious habit of flooring it when I’m irritated.

“Yeah,” Chris says. “You do.”

I press my lips together, wondering how much I should tell a complete stranger. “I got separated from my dad. I’m going to meet him somewhere.”

“How far are you driving?”

“Towards Squaw Valley,” I reply, vague.

“You’re going to keep it a secret?” He smiles. “You’re what…sixteen?”

“I’m nineteen,” I snap. “Come on. At least try to guess accurately.”

He chuckles.

“Sorry,” he says, holding his hands up. “I’m just trying to figure you out.”

“You’re doing a lousy job.” I keep my eyes trained on the road, taking the curves slow and the straightaways like a racecar driver on steroids. “I don’t trust you yet, by the way. Keep that in mind.”

“Duly noted.” His voice is heavy with amusement. “I’ll try not to tick you off.”

I snort.

“Good luck with that.”

“Look.” Chris points to a spot of light ahead on the road. “Turn off the headlights.”

I open my mouth to make a smart comment but decide to save it for later. I snap the headlights off and we peer into the darkness as I slow the car down. There seems to be a group of people on the road, almost invisible at night.

“They’re blocking the road,” Chris says. “Turn the car around.”

“I can’t! I’m doing sixty!”

“Then slow down and make a U-turn.”

His words are quick, totally casual. I take my foot off the gas but we’re moving too quickly towards the group. I lay on the brake and stop just in time, Chris looking out the window as the people start running towards us.