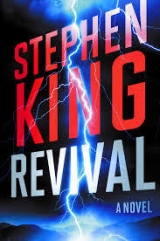

Текст книги "Revival"

Автор книги: Stephen Edwin King

Жанр:

Ужасы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 12 (всего у книги 24 страниц)

We were. Crystal.

• • •

Georgia Donlin was just as beautiful in 2008 as in 1992, but she’d put on a few pounds, there were streaks of silver in her dark hair, and she was wearing bifocals. “You don’t happen to know what’s got him all fired up this morning, do you?” she asked me.

“No clue.”

“He started cussing, then he laughed a little, then he started cussing again. Said he fucking knew it, said that son of a bitch, then threw something, it sounded like. All I want to know is if somebody’s gonna get fired. If that’s the case, I’m taking a sick day. I can’t deal with confrontation.”

“Says the woman who threw a pot at the meat delivery man last winter.”

“That was different. That four-oh-four son of a bitch tried to caress my butt.”

“A four-oh-four with good taste,” I remarked, and when she gave me the stinkeye: “Just sayin.”

“Huh. Last few minutes it’s been all quiet in there. I hope he didn’t give himself a heart attack.”

“Maybe it was something he saw on TV. Or read in the paper?”

“TV went off fifteen minutes after I came in, and as for the Camera and the Post, he stopped takin em two months ago. Says he gets everything from the Internet. I tell him, ‘Hugh, all that Internet news is written by boys not old enough to shave and girls hardly out of their training bras. It’s not to be trusted.’ He thinks I’m just a clueless old lady. He doesn’t say it, but I can see it in his eyes. Like I don’t have a daughter who’s taking computer courses at CU. Bree’s the one who told me not to trust that bloggish crap. Go on, now. But if he’s sittin in his chair dead of vapor lock, don’t call me to give him CPR.”

She moved away, tall and regal, the gliding walk no different from that of the young woman who had brought the iced tea into Hugh’s office sixteen years before.

I tapped a knuckle on the door. Hugh wasn’t dead, but he was slumped behind his oversize desk, rubbing his temples like a man with a migraine. His laptop was open in front of him.

“Are you going to fire someone?” I asked.

He looked up. “Huh?”

“Georgia says if you’re going to fire someone, she’s taking a sick day.”

“I’m not going to fire anyone. That’s ridiculous.”

“She says you threw something.”

“Bullshit.” He paused. “I did kick the wastebasket when I saw the shit about the holy rings.”

“Tell me about the holy rings. Then I’ll give the wastebasket another ritual kick and go to work. I’ve got sixteen billion things to do today, including learning two tunes for that Gotta Wanna session. A wastebasket field goal might be just the thing to get me jump-started.”

Hugh went back to rubbing his temples. “I thought this might happen, I knew he had it in him, but I never expected anything quite this . . . this grand. But you know what they say—go big or go home.”

“No fucking clue what you’re talking about.”

“You will, Jamie, you will.”

I parked my butt on the corner of his desk.

“Every morning I watch the six AM news while I do my crunches and pedal the stationary bike, okay? Mostly because watching the weather chick has its own aerobic benefits. And this morning I saw an ad for something besides magic wrinkle creams and Time-Warner golden oldie collections. I couldn’t believe it. Couldn’t, fucking, believe it. At the same time I could.” He laughed then, not a this-is-funny laugh but an I-can’t-fucking-believe-it laugh. “So I turn off the idiot box and investigate further on the Internet.”

I started around his desk but he held up a hand to stop me. “First I have to ask you if you’ll go on a man-date with me, Jamie. To see someone who has—after a couple of false starts—finally realized his destiny.”

“Sure, I guess so. As long as it isn’t a Justin Bieber concert. I’m a little long in the tooth for the Bieb.”

“Oh, this is much better than the Bieb. Take a look. Just don’t let it burn your eyes.”

I walked around the desk and met my fifth business for the third time. The first thing I noticed was the hokey hypnotist’s stare. His hands were spread to either side of his face, and he was wearing a thick gold band on the third finger of each.

It was a poster on a website headed PASTOR C. DANNY JACOBS HEALING REVIVAL TOUR 2008.

OLD-TIME TENT REVIVAL!

JUNE 13–15

NORRIS COUNTY FAIRGROUNDS

20 Miles East of Denver

FEATURING FORMER “SOUL SINGER” AL STAMPER

FEATURING THE GOSPEL ROBINS, WITH

DEVINA ROBINSON

***AND***

EVANGELIST C. DANNY JACOBS

AS SEEN ON THE DANNY JACOBS HOUR

OF HEALING GOSPEL POWER

RENEW YOUR SOUL THROUGH SONG

REFRESH YOUR FAITH THROUGH HEALING

THRILL TO THE STORY OF THE HOLY RINGS,

TOLD AS ONLY PASTOR DANNY CAN!

“Bring hither the poor, and the maimed, and the halt, and the blind; compel them to come in, that my house may be filled.” Luke 14:21 and 23.

WITNESS GOD’S POWER TO CHANGE

YOUR LIFE!

FRIDAY 13TH: 7 PM

SATURDAY 14TH: 2 PM and 7 PM

SUNDAY 15TH: 2 PM and 7 PM

GOD SPEAKS SOFTLY (1 KINGS 19:12)

GOD HEALS LIKE LIGHTNING (MATTHEW 24:27)

COME ONE!

COME ALL!

BE RENEWED!

At the bottom was a photo of a boy throwing away his crutches while a congregation stood watching with expressions of joyous awe. The caption below the photo read Robert Rivard, healed of MUSCULAR DYSTROPHY 5/30/07, St. Louis, Mo.

I was stunned, the way a person would be, I suppose, if he caught sight of an old friend who has been reported dead or arrested for committing a serious crime. Yet part of me—the changed part, the healed part—wasn’t surprised. That part of me had been waiting for this all along.

Hugh laughed and said, “Man, you look like a bird flew into your mouth and you swallowed it.” Then he spoke aloud the only coherent thought I had in my brain at that moment. “Looks like the Rev’s up to his old tricks.”

“Yes,” I said, then pointed at the reference to the Book of Matthew. “But that verse isn’t about healing.”

He raised his eyebrows. “I never knew you were a Bible scholar.”

“There’s a lot you don’t know,” I said, “because we never talk about him. But I knew Charlie Jacobs long before Tulsa. When I was a little boy, he was the minister at our church. It was his first pastoral job, and I would have guessed it was his last. Until now.”

His smile went away. “You’re shitting me! How old was he, eighteen?”

“I think around twenty-five. I was six or seven.”

“Was he healing people back then?”

“Not at all.” Except for my brother Con, that was. “In those days he was straight-up Methodist—you know, Welch’s grape juice at communion instead of wine. Everyone liked him.” At least until the Terrible Sermon. “He quit after he lost his wife and son in a road accident.”

“The Rev was married? He had a kid?”

“Yes.”

Hugh considered. “So he’s actually got a right to at least one of those wedding rings—if they are wedding rings. Which I doubt. Look at this.”

He went to the band at the top of the website page, put the cursor on MIRACLE TESTIMONY, and clicked. The screen now showed a line of YouTube videos. There were at least a dozen.

“Hugh, if you want to go see Charlie Jacobs, I’m happy to tag along, but I really don’t have time to discuss him this morning.”

He regarded me closely. “You don’t look like someone who swallowed a bird. You look like somebody gave you a hard punch to the gut. Look at this one vid, and I’ll let you go.”

Halfway down was the boy from the poster. When Hugh clicked on it, I saw the clip, which was only a little over a minute long, had racked up better than a hundred thousand views. Not quite viral, but close.

When the picture started to move, someone shoved a microphone with KSDK on it into Robert Rivard’s face. An unseen woman said, “Describe what happened when this so-called healing took place, Bobby.”

“Well, ma’am,” Bobby said, “when he grabbed on my head, I could feel the holy wedding rings on the sides, right here.” He indicated his temples. “I heard a snap, like a stick of kin’lin wood. I might have passed out for a second or two. Then this . . . I don’t know . . . warmth went down my legs . . . and . . .” The boy began to weep. “And I could stand on em. I could walk! I was healed! God bless Pastor Danny!”

Hugh sat back. “I haven’t watched all the other testimonials, but the ones I have watched are pretty much the same. Remind you of anything?”

“Maybe,” I said. Cautiously. “What about you?”

We had never discussed the favor “the Rev” had done for Hugh—a favor big enough to cause the boss of the Wolfjaw Ranch to hire a barely straight heroin addict on the basis of a phone call.

“Not while you’re pressed for time. What are you doing for lunch?”

“Ordering in pizza. After the c&w chick exits, there’s a guy from Longmont . . . sheet says he’s ‘a baritone interpreter of popular song’ . . .”

Hugh looked blank for a moment, then slapped his forehead with the heel of his hand. “Oh my God, is it George Damon?”

“Yeah, that’s the name.”

“Christ, I thought that sucker was dead. It’s been years—before your time. The first record he made with us was Damon Does Gershwin. Long before CDs this was, although eight-tracks might have been around. Every song, and I mean every fucking song, sounded like Kate Smith singing ‘God Bless America.’ Let Mookie handle him. They go back. If the Mookster screws up, you can fix it in the mix.”

“You sure?”

“Yes. If we’re going to see the Rev’s fine and holy shit-show, I want to hear what you know about him first. Probably we should have had this conversation years ago.”

I thought that over. “Okay . . . but if you want to get, you have to give. A full and fair exchange of information.”

He laced his hands together on the not inconsiderable middle of his western-style shirt and rocked back in his chair. “It’s nothing I’m ashamed of, if that’s what you’re thinking. It’s just so . . . unbelievable.”

“I’ll believe it,” I said.

“Maybe so. Before you leave, tell me what that verse in Matthew says, and how you know it.”

“I can’t quote it exactly after so many years, but it’s something like, ‘As the lightning flashes from east to west, covering the sky, so shall be the coming of Jesus.’ It’s not about healing, it’s about the apocalypse. And I remember it because it was one of Reverend Jacobs’s favorites.”

I glanced at the clock. The long-legged country girl—Mandy something-or-other—was a chronic early bird, she was probably already sitting on the steps outside Studio 1 with her guitar propped up beside her, but there was one thing I had to know right then. “What did you mean when you said you doubted they were wedding rings?”

“Didn’t use the rings on you, huh? When he took care of your little drug problem?”

I thought of the abandoned auto body shop. “Nope. Headphones.”

“This was in what? 1992?”

“Yes.”

“My experience with the Rev was in 1983. He must have updated his MO in the time between. He probably went back to the rings because they seem more religious than headphones. But I bet he’s moved ahead with his work since my time . . . and yours. That’s the Rev, wouldn’t you say? Always trying to take it to the next level?”

“You call him the Rev. Was he preaching when you met him?”

“Yes and no. It’s complicated. Go on, get out of here, your girl will be waiting. Maybe she’ll be wearing a miniskirt. That’ll take your mind off Pastor Danny.”

As a matter of fact, she was wearing a mini, and those legs were definitely spectacular. I hardly noticed them, though, and I couldn’t tell you a thing she sang that day without checking the log. My mind was on Charles Daniel Jacobs, aka the Rev. Now known as Pastor Danny.

• • •

Mookie McDonald bore his scolding about the soundboard quietly, head down, nodding, at the end promising he would do better. He would, too. For awhile. Then, a week or two from now, I’d come in and find the board on again in 1, 2, or both. I think the idea of putting people in jail for smoking the rope is ludicrous, but there’s no doubt in my mind that long-term daily use is a recipe for CRS, also known as Can’t Remember Shit.

He brightened up when I told him he’d be recording George Damon. “I always loved that guy!” the Mookster exclaimed. “Everything he sang sounded like—”

“Kate Smith singing ‘God Bless America.’ I know. Have a good time.”

• • •

There was a pretty little picnic area in a grove of alders behind the big house. Georgia and a couple of the office girls were having their lunch there. Hugh led me to a table well away from theirs and took a couple of wrapped sandwiches and two cans of Dr Pepper from his capacious manpurse. “Got chicken salad and tuna salad from Tubby’s. You choose.”

I chose tuna. We ate in silence for awhile, there in the shadow of the big mountains, and then Hugh said, “I also used to play rhythm, you know, and I was quite a bit better than you.”

“Many are.”

“At the end of my career I was in a band out of Michigan called Johnson Cats.”

“From the seventies? The guys who wore those Army shirts and sounded like the Eagles?”

“It was actually the early eighties when we broke through, but yeah, that was us. Had four hit singles, all off the first album. And do you want to know what got that album noticed in the first place? The title and the jacket, both my idea. It was called Your Uncle Jack Plays All the Monster Hits, and it had my very own Uncle Jack Yates on the cover, sitting in his living room and strumming his ukulele. Inside, lots of heaviness and monster fuzz-tone. No wonder it didn’t win Best Album at the Grammys. That was the era of Toto. Fucking ‘Africa,’ what a piece of crap that was.”

He brooded.

“Anyway, I was in the Cats, had been for two years, and that’s me on the breakout record. Played the first two tour dates, then got let go.”

“Why?” Thinking, It must have been drugs. Back then it always was. But he surprised me.

“I went deaf.”

• • •

The Johnson Cats tour started in Bloomington—Circus One—then moved on to the Congress Theater in Oak Park. Small venues, warmup gigs with local ax-whackers to open. Then to Detroit, where the big stuff was scheduled to start: thirty cities, with Johnson Cats as the opening act for Bob Seger and the Silver Bullet Band. Arena rock, the real deal. What you dream of.

The ringing in Hugh’s ears started in Bloomington. At first he dismissed it as just part of the price you paid when you sold your soul for rock and roll—what self-respecting player didn’t suffer tinnitus from time to time? Look at Pete Townshend. Eric Clapton, Neil Young. Then, in Oak Park, the vertigo and nausea started. Halfway through their set, Hugh reeled offstage and hurled into a bucket filled with sand.

“I still remember the sign on the post above it,” he told me. “USE FOR SMALL FIRES ONLY.”

He finished the gig—somehow—took his bows, and reeled offstage.

“What’s wrong with you?” Felix Granby asked. He was the lead guitarist and lead vocalist, which meant to the public at large—the portion of it that rocked, at least—he was Johnson Cats. “Are you drunk?”

“Stomach flu,” Hugh said. “It’s getting better.”

He thought it was true; with the amps off, the tinnitus did seem to be ebbing. But the next morning it was back, and other than the hellish ringing, he could hear almost nothing.

Two members of Johnson Cats fully grasped looming disaster: Felix Granby and Hugh himself. Only three days ahead was the Silverdome, in Pontiac. Capacity ninety thousand. With Detroit favorite Bob Seger headlining, it would be almost full. The JC was on the cusp of fame, and in rock and roll, such chances rarely come around a second time. So Felix Granby had done to Hugh what Kelly Van Dorn of White Lightning had done to me.

“I bore him no grudge,” Hugh said. “If our positions had been reversed, I might have done the same. He hired a session player out of L’Amour Studio in Detroit, and it was that guy who went onstage with them that night at the Dome.”

Granby did the firing in person, not by talking but by writing notes and holding them up for Hugh to read. He pointed out that while the other members of the JC came from middle-class families, Hugh was from real money. He could fly back to Colorado in a comfy seat at the front of the plane, and consult all the best doctors. Granby’s last note, written in capital letters, read: U WILL BE BACK WITH US BEFORE U KNOW IT.

“As if,” Hugh said as we sat in the shade, eating our sandwiches from Tubby’s.

“You still miss it, don’t you?” I asked.

“No.” Long pause. “Yes.”

• • •

He did not go back to Colorado.

“If I had’ve, I sure wouldn’t have flown. I had an idea my head might explode once we got above twenty thousand feet. Besides, home wasn’t what I wanted. All I wanted to do was lick my wounds, which were still bleeding, and Detroit was as good a lickin place as any. That’s the story I told myself, anyway.”

The symptoms did not abate: vertigo, nausea ranging from moderate to severe, and always that hellish ringing, sometimes soft, sometimes so loud he thought his head would split open. On occasion all these symptoms would draw back like a tide going out, and then he would sleep for ten or even twelve hours at a stretch.

Although he could have afforded better, he was living in a fleabag hotel on Grand Avenue. For two weeks he put off going to a doctor, terrified that he would be told he had a malignant and inoperable brain tumor. When he finally did force himself into a doc-in-the-box on Inkster Road, a Hindu medic who looked about seventeen listened, nodded, did a few tests, and urged Hugh to check himself into a hospital for more tests, plus experimental antinausea medications he himself could not prescribe, so sorry.

Instead of going to the hospital, Hugh began taking long and pointless safaris (when the vertigo permitted it, that was) up and down the fabled stretch of Detroit road known as 8-Mile. One day he passed a storefront with radios, guitars, record players, tape decks, amplifiers, and TVs in the dusty window. According to the sign, this was Jacobs New & Used Electronics . . . although to Hugh Yates, most of it looked beat to shit and none of it looked new.

“I can’t tell you exactly why I went in. Maybe it was some creeped-out nostalgia for all that audio candy. Maybe it was self-flagellation. Maybe I just thought the place would be air-conditioned, and I could get out of the heat—boy, was I ever wrong about that. Or maybe it was the sign over the door.”

“What did it say?” I asked.

Hugh smiled at me. “You Can Trust the Rev.”

• • •

He was the only customer. The shelves were packed with equipment a lot more exotic than the wares in the window. Some stuff he knew: meters, oscilloscopes, voltometers and voltage regulators, amplitude regulators, rectifiers, power inverters. Other stuff he didn’t recognize. Electric cords snaked across the floor and wires were strung everywhere.

The proprietor came out through a door framed in blinking Christmas lights (“Probably a bell jingled when I came in, but I sure didn’t hear it,” Hugh said). My old fifth business was dressed in faded jeans and a plain white shirt buttoned to the collar. His mouth moved in Hello and something that might have been Can I help you. Hugh tipped him a wave, shook his head, and browsed along the shelves. He picked up a Stratocaster and gave it a strum, wondering if it was in tune.

Jacobs watched him with interest but no detectable concern, although Hugh’s rock-dog ’do now hung in unwashed clumps to his shoulders and his clothes were equally dirty. After five minutes or so, just as he was losing interest and getting ready to walk back to the fleabag where he now hung his hat, the vertigo hit. He reeled, putting out one hand and knocking over a disassembled stereo speaker. He almost recovered, but he hadn’t been eating much, and the world turned gray. Before he hit the shop’s dusty wooden floor, it had turned black. It was my story all over again. Only the location was different.

When he woke up, he was in Jacobs’s office with a cold cloth on his forehead. Hugh apologized and said he would pay for anything he might have broken. Jacobs drew back, blinking in surprise. This was a reaction Hugh had seen often in the last weeks.

“Sorry if I’m talking too loud,” Hugh said. “I can’t hear myself. I’m deaf.”

Jacobs rummaged a notepad from the top drawer of his cluttered desk (I could imagine that desk, littered with snips of wire and batteries). He jotted and held the pad up.

Recent? I saw you w/ guitar.

“Recent,” Hugh agreed. “I have something called Ménière’s disease. I’m a musician.” He considered that and laughed . . . soundlessly to his own ears, although Jacobs responded with a smile. “Used to be, anyhow.”

Jacobs turned a page in his notebook, wrote briefly, and held it up: If it’s Menière’s, I might be able to do something for you.

• • •

“Obviously he did,” I said.

Lunch hour was over; the girls had gone back inside. There was stuff I could be doing—plenty—but I had no intention of leaving until I heard the rest of Hugh’s story.

“We sat in his office for a long time—conversation’s slow when one person has to write his side of it. I asked him how he thought he could help me. He wrote that just lately he’d been experimenting with transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, TENS for short. He said the idea of using electricity to stimulate damaged nerves went back thousands of years, that it was invented by some old Roman—”

A dusty door far back in my memory opened. “An old Roman named Scribonius. He discovered that if a guy with a bad leg stepped on an electric eel, the pain sometimes went away. And that ‘just lately’ stuff was crap, Hugh. Your Rev was playing around with TENS before it was officially invented.”

He stared at me, eyebrows up.

“Go on,” I said.

“Okay, but we’ll come back to this, right?”

I nodded. “You show me yours, I show you mine. That was the deal. I’ll give you a hint: there’s a fainting spell in my story, too.”

“Well . . . I told him that Ménière’s disease was a mystery—doctors didn’t know if it had to do with the nerves, or if it was a virus causing a chronic buildup of fluid in the middle ear, or some kind of bacterial thing, or maybe genetic. He wrote, All diseases are electrical in nature. I said that was crazy. He just smiled, turned to a new page in his pad, and wrote for a longer time. Then he handed it across to me. I can’t quote it exactly—it’s been a long time—but I’ll never forget the first sentence: Electricity is the basis of all life.”

That was Jacobs, all right. The line was better than a fingerprint.

“The rest said something like, Take your heart. It runs on microvolts. This current is provided by potassium, an electrolyte. Your body converts potassium into ions—electrically charged particles—and uses them to regulate not just your heart but your brain and EVERYTHING ELSE.

“Those last words were in capitals. He put a circle around them. When I handed his pad back, he drew something on it, very quick, then pointed to my eyes, my ears, my chest, my stomach, and my legs. Then he showed me what he’d drawn. It was a lightning bolt.”

Sure it was.

“Cut to the chase, Hugh.”

“Well . . .”

• • •

Hugh said he’d have to think it over. What he didn’t say (but was certainly thinking) was that he didn’t know Jacobs from Adam; the guy could be one of the crazybirds that flap around every big city.

Jacobs wrote that he understood Hugh’s hesitation, and felt plenty of his own. “I’m going out on a limb to even make the offer. After all, I don’t know you any more than you know me.”

“Is it dangerous?” Hugh asked in a voice that was already losing tone and inflection, becoming robotic.

The Rev shrugged and wrote.

Won’t kid you, there is some risk involved in applying electricity directly through the ears. But LOW VOLTAGE, OK? I’d guess the worst side effect you’d suffer might be peeing your pants.

“This is crazy,” Hugh said. “We’re insane just to be having this discussion.”

The Rev shrugged again, but this time didn’t write. Only looked.

Hugh sat in the office, the cloth (still damp but now warm) clutched in one hand, seriously considering Jacobs’s proposal, and a large part of his mind found serious consideration, even on such short acquaintance, perfectly normal. He was a musician who had gone deaf and been cast aside by a band he’d helped to found, one now on the verge of national success. Other players and at least one great composer—Beethoven—had lived with deafness, but hearing loss wasn’t where Hugh’s woes ended. There was the vertigo, the trembling, the periodic loss of vision. There was nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, galloping pulse. Worst of all was the almost constant tinnitus. He had always thought deafness meant silence. This was not true, at least not in his case. Hugh Yates had a constantly braying burglar alarm in the middle of his head.

There was another factor, too. A truth not acknowledged until then, but glimpsed from time to time, as if in the corner of the eye. He had remained in Detroit because he was working up his courage. There were many pawnshops on 8-Mile, and all of them sold barrel-iron. Was what this guy was offering any worse than the muzzle of a thirdhand .38 socked between his teeth and pointing at the roof of his mouth?

In his too-loud robot’s voice, he said, “What the fuck. Go ahead.”

• • •

Hugh gazed at the mountains while he told the rest, his right hand stroking his right ear as he spoke. I don’t think he knew he was doing it.

“He put a CLOSED sign in the window, locked the door, and dropped the blinds. Then he sat me down in a kitchen chair by the cash register and put a steel case the size of a footlocker on the counter. Inside it were two metal rings wrapped in what looked like gold mesh. They were about the size of those big dangly earrings Georgia wears when she’s stylin. You know the ones I mean?”

“Sure.”

“There was a rubber widget on the bottom of each, with a wire coming out of it. The wires ran into a control box no bigger than a doorbell. He opened the bottom of the box and showed me what looked like a single triple-A battery. I relaxed. That can’t do much damage, I thought, but I didn’t feel quite so comfortable when he put on rubber gloves—you know, like the kind women wear when they’re washing dishes—and picked up the rings with tongs.”

“I think Charlie’s triple-A batteries are different from the ones you buy in the store,” I said. “A lot more powerful. Didn’t he ever talk to you about the secret electricity?”

“Oh God, many times. It was his hobbyhorse. But that was later, and I never made head or tail of it. I’m not sure he did, either. He’d get a look in his eyes . . .”

“Puzzled,” I said. “Puzzled, worried, and excited, all at the same time.”

“Yeah, like that. He put the rings against my ears—using the tongs, you know—and then asked me to push the button on the control unit, since his own hands were full. I almost didn’t, but I flashed on the pistols in all those pawnshop windows, and I did it.”

“Then blacked out.” I didn’t ask it as a question, because I was sure of it. But he surprised me.

“There were blackouts, all right, and what I called prismatics, but they came later. Right then there was just an almighty snapping sound in the middle of my head. My legs shot out and my hands went up over my head like a schoolkid who’s just desperate to tell the teacher he knows the right answer.”

That brought back memories.

“Also, there was a taste in my mouth. Like I’d been sucking on pennies. I asked Jacobs if I could have a drink of water, and heard myself asking, and broke into tears. I cried for quite awhile. He held me.” At last Hugh turned from the mountains and looked at me. “After that I would have done anything for him, Jamie. Anything.”

“I know the feeling.”

“When I had control of myself again, he took me back out into the shop and put a pair of Koss headphones on me. He plugged into an FM station and kept turning the music down and asking me if I could hear it. I did until he got all the way to zero, and I could almost swear I even heard it then. He not only brought my hearing back, it was more acute than it had been since I was fourteen, and playing with my first jam-band.”

• • •

Hugh asked how he could repay Jacobs. The Rev, only a scruffy guy in need of a haircut and a bath, considered this.

“Tell you what,” he said at last. “There’s little in the way of business here, and some of the people who do wander in are pretty sketchy. I’m going to transport all this stuff to a storage facility on the North Side while I think about what to do next. You could help me.”

“I can do better than that,” Hugh said, still relishing the sound of his own voice. “I’ll rent the storage space myself, and hire a crew to move everything. I don’t look like I can afford it, but I can. Really.”

Jacobs seemed horrified at the idea. “Absolutely not! The goods I have for sale are mostly junk, but my equipment is valuable, and much of it in the back area—my lab—is delicate, as well. Your help would be more than enough repayment. Although first you need to rest a little. And eat. Put on a few pounds. You’ve been through a difficult time. Would you be interested in becoming my assistant, Mr. Yates?”

“If that’s what you want,” Hugh said. “Mr. Jacobs, I still can’t believe you’re talking and I’m hearing you.”

“In a week, you’ll take it for granted,” he said dismissively. “That’s the way it works with miracles. No use railing against it; it’s plain old human nature. But since we have shared a miracle in this overlooked corner of the Motor City, I can’t have you calling me Mr. Jacobs. To you, let me be the Rev.”

“As in Reverend?”

“Exactly,” he said, and grinned. “Reverend Charles D. Jacobs, currently chief prelate in the First Church of Electricity. And I promise not to work you too hard. There’s no hurry; we’ll take our time.”

• • •

“I’ll bet you did,” I said.

“What’s that supposed to mean?”

“He didn’t want you to buy him a moving crew, and he didn’t want your money. He wanted your time. I think he was studying you. Looking for aftereffects. What did you think?”

“Then? Nothing. I was riding a mighty cloud of joy. If the Rev had asked me to rob First of Detroit, I might have given it a shot. Looking back on it, though, you could be right. There wasn’t much to the work, after all, because when you came right down to it, he had very little to sell. There was more in his back room, but with a big enough U-Haul, we could have moved the whole kit and caboodle off the 8-Mile in two days. But he strung it out over a week.” He considered. “Yeah, okay. He was watching me.”