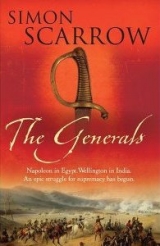

Текст книги "The Generals"

Автор книги: Simon Scarrow

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 34 (всего у книги 45 страниц)

Chapter 54

Marengo, 14 June 1800

The Austrian attack rolled forward just as Lannes’s and Murat’s hastily roused divisions began to arrive on the battlefield. Napoelon glanced at his watch. Just gone eleven in the morning. The enemy would have enough time to break the French army and begin a pursuit long before the fall of night obliged them to break contact. He clenched his fist and struck his thigh.

Why did I not see this?

They were outnumbered at least two to one. Worse still, the Austrians completely outgunned them and their cavalry was better mounted and far more numerous. Already they were manoeuvring to Napoleon’s right towards the village of Castel Ceriolo. The flat dry landscape around Marengo would be ideal for large, sweeping movements of cavalry and Napoleon saw at once that his goal in the imminent battle was not to achieve a victory, but simply to avoid annihilation.

A signal gun fired from the Austrian forces massed to the west and, an instant later, the batteries formed up in front of the infantry spat tongues of flame and were instantly swallowed up in a bank of smoke. A moment later the sound of the discharge rolled across the battlefield like thunder as roundshot carved bloody paths through the ranks of Victor’s men.

Only a handful of French guns were positioned at the centre of Victor’s line and they spat back their defiance, trading shots with the batteries immediately opposite. All the time Victor’s guns were whittled down by the enemy until, no more than a quarter of an hour after the cannonade had begun, the last French eight-pounder was struck squarely on its carriage and a hail of splinters cut down half of the gun crew. The survivors turned and ran for the lines of infantry waiting behind them.

The Austrian guns fell silent, then a moment later the sound of drums and trumpets reached Napoleon. Through the dense bank of gunpowder smoke emerged columns of enemy infantry, the sun glinting off their musket barrels and the officers’ gorgets and swords as they waved their men forward. There was a lull in the noise of battle as the enemy came on, and the French waited, grimly. Then, when it seemed that the two lines could not get much closer, Napoleon heard the order to present arms echo down the French line.Thousands of musket barrels swept up and out, aiming at the enemy no more than seventy paces away.

‘Fire!’Victor bellowed, his booming voice carrying across the battlefield. Stabs of light and swirls of smoke billowed out along the French line like a ribbon of soiled cotton. From his slightly elevated position Napoleon could see the leading ranks of the enemy column tumble down as the volley of musket balls tore into them. But they held their ground, re-formed and marched a short distance closer before deploying into a firing line. Victor’s men managed to get off two more volleys before the Austrians returned fire. Then the fight was swallowed up in an ever-thickening bank of acrid yellow smoke that hung across the battlefield.

Napoleon waited until he was certain that the French line was holding along its front, and then rode forward to General Victor. The veteran greeted him with a salute and a wry shake of the head. ‘They caught us out nicely, sir.’

Napoleon ignored the comment as he returned the salute. ‘You must hold here for as long as possible. Lannes and Murat are moving up to support you. I’ve sent for Desaix.’

‘Desaix? He won’t be able to reach us until long after this battle is over.’

‘Perhaps,’ Napoleon conceded. ‘But he might. Meanwhile we have to hold the Austrians back as long as we can, until tonight at least.Then we’ll concentrate our forces and go on to the attack tomorrow.’

‘If there are any forces left to concentrate,’Victor said quietly. He glanced towards his men, now firing by companies in a continuous rattle of musket fire. ‘Besides, we’re going to run out of ammunition before long. Then we’ll be at their mercy.’

‘If that happens, we’ll fall back on the main camp and resupply the men from there.’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘Remember, Victor.’ Napoleon thrust his arm towards the ground.‘Hold here for as long as possible.That is our only chance of surviving this day.’

‘Yes, sir.’

Napoleon wheeled his horse round and rode along the rear of his line. Whenever the men noticed him, a cheer rose up, before the sergeants and officers bellowed at them to face front and keep firing. The first of the walking wounded were already staggering back from the foremost ranks, clutching their bloody injuries as they made for the rear. When he reached the end of the line it was clear to Napoleon that the main weight of the enemy attack was being thrown at General Watrin’s division, on the right flank. The dead and wounded lay thick on the ground and as the survivors closed ranks, the gaps in between units were growing all the time. So that was the enemy’s plan, Napoleon nodded to himself. Melas intended to crush the French right, then send his cavalry in a sweeping arc to trap the French army against the Bormida and crush them.

Watrin was having his arm bandaged as Napoleon rode up to the small cluster of divisional staff officers.

‘Not serious, I hope.’ Napoleon gestured towards the injury.

‘A flesh wound, sir. That’s all. Nothing compared to what’s happening to my men.’ He glanced at the smoke shrouding his line. Only the rear ranks were clearly visible. In front of them the men in the front lines were no more than dim grey shapes, firing, reloading and firing again. ‘They’re carving us up, sir. I doubt we’ll be able to hold this position for another ten minutes.’

‘You have to,’ Napoleon replied bluntly. ‘Reinforcements will be on the way.You have to hold the enemy back until they arrive. Whatever the cost. Is that clear?’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘Then God be with you, General.’

‘And you, sir.’

By the time Napoleon had returned to his command post on the raised ground behind Marengo, the Austrians had pulled back their battered assault columns and were preparing another attack. As the smoke dispersed and lifted from the battlefield the perilous situation of the French army was clear for all to see.The ground was littered with the dead and wounded of both sides, but whereas the battered units of Napoleon’s army were spread thinly across the ground the enemy were able to mass fresh battalions to continue the fight, and these were forming up, preparing for the next assault.

Berthier approached him, clutching a scribbled note. ‘Victor’s men are down to their last few rounds, and we have only fifteen pieces of artillery left. Victor asks for permission to withdraw before the next attack begins.’

‘No. He must stay where he is.’

‘But, sir,Victor cannot hold them back.’

‘Then he must delay their advance for as long as possible.’

‘At least reinforce him then. We still have Monnier’s division in reserve.’>

Napoleon turned and pointed towards Castel Ceriolo. ‘We need Monnier there. He must hold the flanks.Watrin’s division is all but finished. Give the order for Monnier to advance immediately.’

‘What about Watrin, sir? Should I pull him back?’

Napoleon shook his head, even though he knew that Watrin’s division must collapse under the next attack, unless they were supported. But Monnier’s men were the only forces available to send into the battle and they had to hold the flank. Then Napoleon’s gaze fell on the men of the Consular Guard, two thousand strong and every man a tough veteran.

‘Berthier, send the Guard forward to support Watrin.’

His chief of staff was shocked.‘The Guard? But, sir, if the army breaks and routs, who will protect you?’

‘If the army breaks then I will be beyond need of protection,’ Napoleon replied quietly as he gripped the hilt of his sword. ‘Send the Guard forward.’

Berthier nodded solemnly and turned back to his campaign desk to hurriedly write the orders and hand them to the waiting dispatch riders. As the last of them rode off, he returned to Napoleon’s side.

‘That’s it then, sir. We’ve no more men to put into line against the enemy now. We’re in the hands of fate.’

‘Fate won’t decide this,’ Napoleon replied. ‘It’s a test of courage and endurance . . . And numbers.’

Berthier smiled mirthlessly. ‘Fate has a way of favouring the bigger battalions.’

Napoleon did not reply, but stared out over the battlefield at the Austrians surging forward to attack his thinly stretched army. Could they weather another assault, he wondered? If not, then only Desaix could save them from utter destruction.

After a fresh cannonade the Austrian columns came on again.To the right, opposite the end of Watrin’s division, a large body of cavalry was forming up behind the columns of Austrian infantry. The Consular Guard formed into a square before it marched steadily forward to fill the gap between Watrin’s and Monnier’s divisions.As the enemy saw the guard moving towards them, they turned their attention away from the remnants of Watrin’s division and opened fire on the square. At such close range the veterans were shot down by the score under the withering volleys of the enemy. But each time they steadily closed ranks and continued forward, until at last the order was given to halt, and open fire.

For the moment the Guard was holding its own and Napoleon turned his attention to the far right of the line. The sacrifice of the Guard had not only taken the pressure off the shaken survivors of Watrin’s division, but also given Monnier the chance to form his men up on the right flank, and now his fresh columns rolled forward towards Castel Ceriolo. As Napoleon had hoped, the Austrians began to break contact with Watrin and the remnants of the Consular Guard as they turned to face the new threat. The firing died away for the moment as the French soldiers fell back a few hundred paces and re-formed their line.

A rider approached Berthier, and leaned forward to hand him a note. Berthier glanced at it before turning to Napoleon.‘Victor is pulling back, before he is destroyed.’

For an instant Napoleon was on the verge of shouting an order that Victor should hold his line to the last man, but then cold calm reason asserted itself. Such an order would be madness. Inhuman madness. Instead he nodded. ‘He has done enough.Tell him to withdraw towards the main camp at San Giuliano. Pass the order down the line to all the other commanders.’

Berthier hurried back to his desk. Now that defeat seemed unavoidable, Napoleon felt a tired calmness fill his body. His men had done all they could to stem the Austrian assault, and it was his duty to try to save as many of them as he could. With luck, Desaix might arrive in time to cover their retreat.The loss of this battle would give heart to France’s enemies, and destroy his reputation. The fault, he accepted, was his own. He had misjudged the character of his opponent – the classic mistake of an arrogant commander blinded by faith in his infallibility. Once news of this defeat reached Paris, his days as First Consul were numbered. Bernadotte and Moreau would circle like vultures ready to pluck the power from his bones.

The French army retreated from the battlefield, marching back down the road towards the village of San Giuliano. The men trudged along in silence, the injured being helped by their comrades.As they passed him Napoleon noted the exhausted and anxious expressions on their grime-streaked faces and knew that their travail was not over. Glancing at his watch he saw that it was not yet three o’clock in the afternoon, still early enough for the enemy to mount a pursuit. Beyond Marengo he could see that the centre of the Austrian line was forming into a column whose intention was all too clear. Melas was sending his army after them, determined to complete his victory with one final crushing blow to his defeated enemy. He would do it too, Napoleon realised. A short while earlier he had seen a dense cloud of dust on the far side of the river as one of the Austrian cavalry columns moved out to swing round the retreating French and cut off their escape route. A similar force was massing this side of the river, ready to march towards Novi to act as the other pincer arm.

‘Sir!’ Berthier called out to him and pointed down the retreating column in the direction of the camp. A small party of horsemen was galloping towards them. At their head was a figure with gold braid on his uniform coat. ‘It’s Desaix!’

Napoleon made himself smile as his friend rode up and reined in. Desaix had ridden hard and his horse’s flanks heaved like a blacksmith’s bellows.

‘Sir, it’s good to see you.’ Desaix gestured to the retreating column. ‘I assumed the worst.’

‘I fear the worst is still to come.’ Napoleon pointed out the dust from the enemy cavalry columns. ‘They aim to block our retreat while the main body of the enemy army pursues us down this road. Not a good situation for us, I fear.’

Desaix quickly took stock of the situation and then pulled out his watch before he turned back to Napoleon. ‘This battle is completely lost.’ Then he raised his head defiantly. ‘But there is still time to win another. My leading division is close behind me, sir. If we can form a new line, before San Giuliano, and put every gun we have to the head of the enemy column, then we can stop them dead in their tracks, and take them in the flanks.’

Napoleon considered the idea for a moment and nodded. Desaix was right. If the army continued to retreat they would only be falling into the enemy’s trap. Their only chance was to turn on the pursuit column and attempt to break it.

He cleared his throat. ‘Very well. One last throw of the dice.’

The late afternoon sun slanted across the fields surrounding San Giuliano. The French line was strung out across the plain in a shallow S formation. On the right flank Monnier and the remnants of the Consular Guard were tasked with holding back the enemy column advancing from Castel Ceriolo. The rest of the army was drawn up facing the road to Marengo. In front of San Giuliano Marmont had massed the remaining eighteen guns, and concealed them behind the stone walls and hedges of the villagers’ smallholdings. Beyond them, Desaix and his men stood ready to attack the enemy column. The battered divisions of Victor and Lannes’ stood formed up parallel to the road, but far enough away to remain out of sight. As they waited for the Austrian column to march into view Napoleon rode down the line to offer encouragement to his troops. Every so often, he halted to deliver the same message.

‘Soldiers! You have retreated enough. The enemy thinks we are beaten! He thinks that he is, at last, our master. He thinks that he has beaten us into a corner like a whipped cur.Well, he should know the danger that comes from cornering a wild beast. He is about to get his arse well and truly bitten off!’

The men raised a laugh, and he moved on, until he reached the survivors of the Consular Guard, drawn up in a neat line. They raised their muskets and presented arms as he reined in before them. Napoleon felt his heart sink as he realised that less than half of the men who had so gallantly marched to Watrin’s rescue still remained. He swallowed and took a deep breath as he addressed them.

‘Men of the Guard, you have proved today that you are the bravest of the brave in the French army . . . in any army. If we win this day then all France shall hear of your courage, and the men of the Guard will for ever hold the place of honour wherever I lead our armies into battle.’ He took off his hat and raised it above his head. ‘Your general salutes you!’

Unlike the other units he had addressed the men stood still, staring ahead as if they were on a parade ground, and there was no outburst of cheers. A sergeant at the end of the front rank suddenly shouted out, ‘Chins up!’

The men strained to raise themselves up to their full height and Napoleon could not help smiling at their fearless and fierce sense of elan. He replaced his hat, wheeled his horse about and galloped back to his command post, just behind the centre of Desaix’s line. They did not have long to wait for the enemy column. With drums beating the pace the Austrians marched straight down the road from Marengo. They did not falter for an instant when they saw the French lines waiting for them before San Giuliano, no doubt taking them for little more than a rearguard left behind to delay the Austrians for as long as possible while the main body of the French army fled.

Desaix shook his head. ‘They’re in for a surprise.’

‘That they certainly are,’ Napoleon replied quietly. ‘Signal Marmont to open fire.’

A staff officer relayed the order to a signalman and the flag fluttered up, held aloft for a moment and then swept down. The artillery crews rose up from their places of concealment and hastily cleared away the straw and cut branches hiding their guns. An instant later the cannon roared into life, belching deadly cones of grapeshot into the leading units of the Austrian pursuit column. Gun after gun fired in a rolling cannonade. The leading companies of the white-uniformed enemy were shredded by grapeshot and as the bodies piled into bloody heaps along the road the column stalled. Shocked by the sudden hail of destruction, they stood and endured the slaughter for some minutes before a senior officer attempted to take control. Slowly, too slowly, the head of the column began to deploy to either side of the road, still under heavy fire from Marmont’s guns, which were being worked as swiftly as their crews could manage. The target was so big there was no need to aim carefully and the guns discharged their grapeshot the moment they were reloaded.

After twenty minutes of terrible carnage, the Austrians were still attempting to draw their men up in a battle line. Napoleon realised that this was the moment to strike the decisive blow.

‘Order Marmont to cease fire. Tell Desaix to charge home!’

‘Yes, sir,’ Berthier nodded.

As soon as the last of the guns fell silent, the leading battalions of Desaix’s men marched through the dense bank of smoke and emerged a short distance from the enemy. Napoleon watched as Desaix ordered his men to halt and volley fire, before they advanced to point-blank range and halted to reload and fire again. Volley after volley rang out from both sides, each one wreaking terrible carnage. As he watched Napoleon sensed that the impetus was quickly draining from the French attack. Unless the Austrians broke soon, he doubted that they ever would.

A sudden sheet of flame tore up into the sky a short distance behind the head of the enemy column and Napoleon saw scores of men hurled aside by the blast. The red flame of the explosion faded and a rolling mushroom cloud billowed above the Austrian lines. He saw a crater in the road and scores of blackened bodies and body parts lay scattered around it.

‘Jesus,’ Napoleon muttered in horror. ‘What was that?’

‘Must have been an ammunition wagon,’ Berthier replied. ‘Lucky shot from our side must have set it off.’

The explosion caused a brief lull in the fighting.The Austrians had turned towards the sound of the blast, dazed and frightened. At that moment a trumpet call sounded from Napoleon’s left and he turned and saw that the small body of cavalry covering the left flank was moving, picking up speed as it surged forward down the side of the enemy column, and then wheeled inwards towards the Austrians, still shaken by the blast.

‘The young fool!’ Berthier said through clenched teeth. ‘He’ll get himself killed.’

Napoleon strained his eyes and realised that the cavalry formation belonged to Kellermann, the son of the hero of Valmy, and one of Murat’s most promising officers. Napoleon shook his head. ‘No, he’s done the right thing. It’s perfectly timed. Look!’

Kellermann’s troopers launched themselves into a charge, trumpets blaring and colours rippling in the wind as they spurred their mounts forward, extending their heavy swords until the glinting blades pointed directly at the terrified Austrians in front of them. A few had the presence of mind to turn and fire their muskets at the charging horsemen; then they were engulfed by the French cavalry and the Austrian column shattered. Men threw down their heavy muskets and ran, fleeing back down the road towards Marengo, and away from the advancing lines of the men of Victor’s and Lannes’s divisions. As far as Napoleon could see the battlefield was covered with white-coated figures streaming away from their French pursuers. Large bodies of men, still in column, laid down their arms and surrendered and their colours were snatched from their hands by jubilant Frenchmen.

As dusk gathered over the battlefield Napoleon made his way forward with Berthier. There was a thick belt of bodies where Marmont’s guns had torn into the leading battalions of the enemy column and then two lines of corpses where Desaix’s men had exchanged volleys with the enemy before they had finally broken. From the earliest reports to have reached headquarters it seemed that over five thousand of the enemy had been killed and an even larger number taken prisoner, along with forty guns, fifteen colours and General Zach, the second in command of the Austrian army. Nightfall, and the presence of strong detachments of Austrian cavalry, had ended the French pursuit and across the plain the exhausted men were re-forming their units and marching back to camp.

Amid all the reports there had been no word from Desaix and Napoleon felt a growing concern for his friend as he edged across the battlefield. Then, just outside the hamlet of Vigna Santa, he saw a group of officers gathered beside the road. Amongst them stood an Austrian general, head bowed in shame. Napoleon strode across the corpse-littered ground towards them and saw that they were clustered about a body sprawled on the ground. Napoleon pushed his way through and looked down.

Desaix lay on his back, head flung to one side, eyes wide open. A bloody hole had been torn through his breast. His sword lay at his side.

Napoleon knelt down. He stared at the body, and his throat tightened. No words came to him. His heart felt heavy and he reached forward and closed Desaix’s eyes as Berthier approached the group.

Berthier clapped his hands together as he gazed round the battlfield. ‘My God! We’ve won! We’ve beaten them. Sir, you’ve won a geat victory . . . sir?’ Then he saw Desaix. ‘Oh, no . . .’

‘Excuse me,’ a voice interrupted, in accented French. ‘General Bonaparte?’

Napoleon glanced up and saw the Austrian officer standing over him in the gloom, holding out his sword, handle first. Rising to his feet, Napoleon faced his enemy. General Zach stood stiffly as he surrendered his weapon.

‘To you the victory, General Bonaparte.’

Napoleon took the sword, noting its finely wrought hilt and jewelled guard. He held it for a moment and then shook his head.

‘The victory is not mine. Had it not been for Desaix I would be presenting you with my sword. No, the victory is not mine. Truly, it belongs to another.’

He knelt down again, and placed the sword across Desaix’s chest, and folded the dead man’s arms across the blade. Then he stood up and pushed his way through the cordon of officers and strode back towards his headquarters before anyone could see the first tears welling up in his eyes.