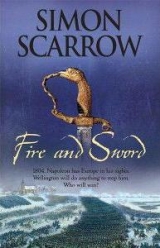

Текст книги "Fire and Sword"

Автор книги: Simon Scarrow

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 26 (всего у книги 44 страниц)

Chapter 34

Arthur

Sheerness, 31 July 1807

There was no putting it off any longer, Arthur realised. It would be the very last task he carried out before he boarded HMS Prometheus. The warship lay at anchor, a quarter of a mile from the wharf, and he could see her clearly through the window of the room he had taken in a Harwich inn. In the dying light he stared at the dark hull with the two broad stripes of yellow indicating her gun decks. Above towered the masts and spars, seemingly caught like insects in the intricate web of her rigging. The brigade that Arthur commanded had already boarded the Prometheusand the large merchant ships anchored astern of the warship. The men were packed along the decks, crowded in with the sailors and marines. More men, together with equipment and supplies, were loaded in the holds of the merchant ships.

The loading was complete and it only remained for Lord Cathcart, the commander of the expeditionary force, to give the order for the fleet to put to sea. As yet the destination of the force was known only to a handful of men in the government and Lord Cathcart, who had been told in the last few days before departure. He had told his senior officers where they were headed – Denmark – but nothing about the purpose of sending the army there. It was puzzling, since Britain was not at war with the Danes. Not yet. Arthur shook his head wearily. Portland’s government seemed hell-bent on provoking neutral powers. The recent policy allowing the Royal Navy to seize vessels, of any nation, suspected of trading with France had outraged them all.

With a sigh, he pulled a sheet of paper across the desk and reached for his pen. He dipped the nib into the inkwell, tapped off the excess and held the pen over the blank sheet.This was not going to be an easy letter to write. As far as Arthur knew, Kitty had no idea that he was about to sail off to war. He knew that he should have told her long before, but Kitty being the nervous, uncertain creature that she was he had told himself that it would be best to present her with a fait accompli, rather than letting her fret for weeks while he prepared his men for war. It did occur to Arthur that this delay in informing her might be construed as ignoble, and have the odour of cowardice, but those who knew Kitty as he did would be well aware that the delay was for the best. He drew a deep breath and began.

My Darling Kitty, I write to tell you that I am to embark on a ship this night to join a small army being sent to fight the French. I have been given command of a brigade and you will be delighted to know that your younger brother Edward is to serve under me. Hopefully it will be the making of him.As for me, I must apologise for being reticent in informing you of my inclusion in this expedition. Given that you are expecting our second child, I did not want to burden your excitable nature with the news that I am returning to active service. Please forgive me, my dearest Kitty, I did not mean to be deceitful.

He paused and frowned as he re-read his last words. She would see through that in an instant, he mused. Of course he was being deceitful; there was no other word for it. But it could not be helped. If Arthur had felt confident that Kitty would receive the news with stoic calm he would have had no hesitation in telling her.As it was, his wife was a very long way from being stoic in disposition and so a measure of deceit was necessary, he told himself, for her own good. He dipped the pen into the inkwell again and continued.

I entrust the running of our household to you and have instructed the family’s agent in Dublin to assist you in your duties, and advance you whatever sums you require, within reason. Try to be brave, my dearest Kitty, and God bless you.

Arthur laid down his pen and read over the brief note. It was very brief, he decided. Perhaps too brief, given that it might well be the last word she ever had from him, apart from being the first intimation she would receive of his involvement in the coming campaign. There was no helping that. He had said what needed to be said and that was that. Folding the paper briskly, Arthur sealed it and thrust it on to the pile of letters he had already written to family, friends and sundry creditors promising to clear accounts the moment he returned. He rang the handbell on the corner of his small desk and a moment later the door opened and the corporal who served as his chief clerk entered.

‘Sir?’

Arthur indicated the letters.‘Add these to the post bag, and once that is done get yourself aboard the Prometheus, Jenkins.’

‘Yes, sir.’

When the corporal had closed the door behind him Arthur stretched back in his chair and folded his arms behind his head. His work was finally done. All preparations and obligations had been tended to and now he was about to set off on campaign. There would be dangers to be sure, a voyage by sea not the least of them, but there was great contentment to be gained from the prospect of leaving behind all the petty duties and annoyances of his post as Chief Secretary in Dublin.

No more patronage to dispense. No more wearisome attempts to balance the interests of the various religious communities in Ireland. No more poring over the reports from secret agents paid to sniff out the faintest whiff of disloyalty and rebellion amongst those who aspired to independence for Ireland. There was a brief lull in his thoughts before he was prepared to admit that the prospect of escaping Kitty and her cloying affection and anxiety over his feelings towards her pleased him as well. It was a sad state of affairs when a husband felt that way, he chided himself. But then not every husband had to deal with someone like Kitty. Still, he would be free of it all for some months, and be able to dedicate himself to the unambiguous duty of fighting the French.

Leaning back, Arthur crossed his hands behind his head and gazed out of the window again towards the shipping resting peacefully at anchor in the sunset.That dog, Bonaparte, had the very good fortune of being the absolute authority in every situation, martial or civil, he mused with a touch of envy. And while the Emperor might have to suppress plots against him, at least he did not find himself enmeshed in the sensitivities of others, as Arthur was. He stared out of the window a moment longer, before wearily rising up and quitting the room.

The small fleet of ships from Sheerness put out to sea at first light and joined the larger convoy that had sailed from Deal. As the ships braced up and began to heel to windward Arthur stood on the quarterdeck and watched as the officers and sailors of the Prometheuscompleted the final adjustments to their sails and the warship settled steadily on her course. Only then were the soldiers permitted on deck, and those who were suffering from the unfamiliar motion rushed to the side and hung their heads over.The rest examined the vessel with curiosity, or simply sat and watched the restless patterns of the waves. The coast of England was little more than an irregular strip of grey between the sea and the sky, and Arthur was slightly surprised that he felt no sense of regret at leaving his country behind. Instead he clasped the ship’s rail and closed his eyes as he relished the salty wind sweeping across his face and ruffling his cropped hair.

An hour later, the coast was no longer in sight, and Arthur drew one last deep breath of the fresh air before he turned away and made for the gangway leading towards the officers’ cabins that lined each side of the wardroom. He had been allotted the cabin of the first lieutenant of the warship, who had simply moved into the next cabin and obliged the ship’s most junior lieutenant to bed down in the midshipmen’s berth. Despite being the quarters of the second in command of the ship, the cabin was barely large enough to contain a cot, a desk and a chair. One of Arthur’s chests was tucked under the cot; the others were in the hold with the rest of the brigade’s baggage. His writing case lay on the desk, and sitting down he flipped back the flap and drew out the orders that had come to him from the War Office a few days before. A short note on the cover of the sealed package instructed him not to open them until out of sight of land, and now he drew a small letter knife from one of the pockets of the writing case and slit the seal. He felt his heart quicken a little as he opened the papers out on the desk. Now he would finally discover the reason for despatching Lord Cathcart’s expeditionary force to Denmark.

His eyes skipped over the preliminary formalities and focused on the main section. He read that the current mission was of the utmost importance to the safety of Britain. The Foreign Secretary, George Canning, had discovered through agents the secret clauses of the recent treaty signed between France and Russia, one of which had detailed France’s intention to seize the fleets of Denmark and Portugal, the last neutral powers in Europe.There was already an army of thirty thousand Frenchmen gathered at Hamburg, poised to invade Denmark the moment the Emperor gave the word. Accordingly, Canning had instructed Denmark to sail her ships to British ports where they would be safe from the Emperor’s clutches for the duration of the war. Denmark had refused to comply and so Lord Cathcart and a fleet of warships had been sent to take the vessels by force.

‘Good God,’ Arthur muttered, and paused a moment to reflect on the situation. Canning was certainly taking the bull by the horns.Arthur could understand and agree with the strategic necessity of such a move, but he was astonished by the gall of the Foreign Minister. Canning would surely be vilified by the Whigs, and some of his own party, and by almost every nation in Europe for such an act. He picked up the orders and read on.

Once the Danish fleet was removed from Copenhagen, the government would be turning its sights on the Portuguese navy. A diplomatic solution was sought, but if that failed it was possible that Lord Cathcart’s force would be required to perform a subsequent operation in Lisbon. The orders ended with a reminder that should either fleet fall into French hands the Emperor would have adequate naval power to force a crossing of the Channel and an invasion of Britain.

Arthur lowered the sheet of paper. He carefully folded it and returned it to his writing case before he leaned back and stared at the stout timber of the bulkhead above the desk, deep in thought.

There would be a fight. There was no doubt of that. Even though Denmark had little sympathy with France, she would be sure to resist any attempt by Britain to remove her fleet. Equally, it was possible that Bonaparte had already given orders for the invasion of Denmark and the seizure of the fleet at Copenhagen. If that was the case then Lord Cathcart might well be caught between the Danes and the French and his position would be precarious indeed. Everything would depend on the speed of the operation. Copenhagen must be taken, and the Danish fleet captured, before the French could react.

The fleet sailed due north, out of sight of land, to avoid being sighted. A screen of frigates sailed in an arc ahead of the convoy to ward off any merchant ships, privateers or the few enemy navy vessels that dared to venture on to the high sea. On the second day the convoy turned east and the ships’ crews busily wore their vessels round and began the final approach towards the coast of Denmark. Arthur had informed his officers of the final destination, but not the men, and they now crowded the ship’s side to see the low coastline, punctuated by tiny islands and rocky outcrops.

The sails were reefed in as the ships closed on the coast, and as the daylight faded the flagship gave the order to heave to and drop anchor. Several small craft sailed closer to the shore to reconnoitre the approaches to the Danish capital, while on board the PrometheusArthur passed the word for the men under his command to be ready to begin landing at short notice. The night passed slowly and the dark hulks of the British fleet gently pitched and rolled at their anchors, while the men aboard huddled expectantly against the sides. As he walked down their lines, dimly illuminated by bulkhead lanterns, Arthur could sense that they were in high spirits. The younger men were full of nervous excitement, while the veterans sat and waited with stoic expressions, or simply took advantage of the opportunity to sleep, not knowing when the next chance would come.

Then, as the first glimmer of dawn lit the horizon, the flagship gave the signal to make sail. Across the calm surface of the sea came the steady clanking as the crews strained at their windlasses to haul in the thick anchor cables with the great weight of the iron sea anchors at the ends of them. One by one, the ships edged forward, taking up their stations as best they could in the light breeze and making towards the coast at an angle until at noon the signal came to drop anchor a mile from the shore opposite a long sandy beach fringed with grassy dunes.

When Arthur took out his spyglass and examined the horizon he could just make out some spires and perhaps the faint mass of buildings away to the east.

‘I think that’s Copenhagen,’ he muttered as he handed the glass to General Stewart, his second in command. ‘Over there.’

Stewart was an experienced officer with a steady, though unspectacular, history of promotion. Even though he respected the man, Arthur suspected that someone at Horseguards had appointed him to Arthur’s brigade to nursemaid its young commander.

Stewart squinted through the eyepiece as he steadied the instrument and adjusted for the slight roll of the Prometheus.‘I believe you are right, sir. And there’s the reception committee.’

He lowered the glass and pointed towards the beach. A group of horsemen had emerged from the dunes and ridden to the water’s edge to examine the shipping spread out across the sea.There was a brief flash as a telescope was trained on the fleet, and then the horsemen turned and rode off at a gallop, disappearing back into the dunes.

‘There goes the element of surprise,’ said Arthur. ‘The Danes will be ready enough for us soon.’

‘Aye.’ Stewart nodded. ‘There’ll be plenty of blood shed before this is all over. One way or another.’

‘Deck there!’ a voice called from aloft and Arthur turned and tilted his head back to see one of the sailors high up on the mainmast thrusting his arm out. ‘Boat approaching!’

A launch was advancing from the direction of the flagship and Arthur could see the red coat of an army officer sitting at the stern beside the midshipman in command of the boat.The oars rose and fell rhythmically as the small vessel approached the towering sides of the Prometheus, and as it hooked on to the chains the army officer scrambled awkwardly up the side and on to the deck. Glancing round, he spied Arthur and came striding towards him.

He saluted and held out a folded slip of paper. ‘Orders from Lord Cathcart, sir.’

Arthur nodded. He unfolded the paper and skimmed over the contents before he looked up. ‘Very well. Tell his lordship that I will begin at once.’

‘Yes, sir.’

Arthur turned to Stewart, who was watching him expectantly. ‘Lord Cathcart intends to land the army today. Our brigade is to go in first and establish a beachhead, before advancing towards Copenhagen.’

Stewart grinned wolfishly and rubbed his hands together.‘That’s the ticket! At bloody last. I’ve had enough of this tub and need to get my boots on dry land.’

Arthur nodded. ‘Pass the word to all officers.They are to have their men ready to go ashore at once.We’ll have the first three companies on deck ready to load.The rest can wait below.’

‘Aye, sir.’ Stewart saluted and turned to march away across the quarterdeck. He cupped a hand to his mouth and bellowed,‘All officers on me! Sergeants, form your men up. First three companies of the battalion only on deck! We’re ordered to lead the attack, lads!’

One of the soldiers punched his fist into the air, and cheered at the top of his voice. Instantly the cry was taken up by the other men as they hurried to their stations. Arthur could not help smiling at their high spirits.Then he turned towards the shore and his smile faded.Within a matter of hours the gleaming sands of the beach and the dunes beyond might well be covered in blood and bodies.The prospect of action did not scare him in the least, he reflected calmly. Only the consequences of it.

He turned away and made for the gangway to collect his sword and pistols from his cabin before he led the first wave of British troops to land on Danish soil.

Chapter 35

‘Easy oars!’ the midshipman cried out and the sailors ceased rowing, allowing the Prometheus’s launch to continue forward under its own way through the gentle waves breaking on the flat stretch of sand. Overhead the sky was a deep blue and the sun blazed down from its zenith. Fortunately a comfortable breeze cooled the faces of the men in the boat and the air was punctuated with the shrill cries of curious seagulls as they whirled above the boats. There was a sudden lurch under the keel and the launch slid to a halt, rested a moment, then was carried forward another few feet by the next wave. Two seamen in the prow hopped over the side and held the launch steady.Arthur was sitting close to the bows and when the boat was solidly grounded he was the first of his men to rise up. He clambered over the side into the knee-deep surf with a splash, and waded ashore.

‘Over yer go, lads!’ a sergeant bellowed. ‘Don’t want the general to fight ’em all on ’is own now! Move yerselves!’

The redcoats climbed out of the launch, muskets held clear of the water, and made their way ashore, emerging from the sea with drenched boots and trousers from the thigh down. On either side, the other boats from the warship ground softly on to the sand and more men piled over the side and surged ashore, until the first company was complete and the sergeant ordered them to form up ten paces beyond the surf. The moment the last of the soldiers was out of the launches the crews pushed their boats back into the sea until they had cleared enough distance to turn round and return to the ship to collect the next company of redcoats.

Stewart made his way over to Arthur and nodded to the dunes rising up ahead of them. ‘Shall I post some pickets up there, sir?’

‘Yes, of course. See to it, please.’

Stewart took the nearest ten men of the Light Company and trotted away across the sand. Arthur watched him with a thoughtful look. He had been about to order the pickets forward himself and now Stewart would no doubt assume he had scored a point over his superior. At some point the man was going to have to be firmly reminded who was in charge. But there was no time for that now. Arthur turned towards the gap in the dunes, a quarter of a mile further along the beach, where the Danish horsemen had appeared earlier. He called the captain of the Light Company over.

‘Sir?’

‘See that gap?’

The captain followed the direction that Arthur pointed out. ‘Yes, sir.’

‘Take the rest of your company over there and form them in line across it. They are not to fire on any Danish soldiers they may encounter. If we can avoid a confrontation we must.’

‘And if they fire on us, sir?’

‘Make every attempt to parley, first. If they are still not amenable to persuasion you may fire on them. Now off you go.’

As the captain led his men down the beach at the double Arthur glanced back towards the ships. The first boats were still rowing back and it would be at least half an hour before they returned. More boats were putting out from the other ships to help convey the rest of the brigade ashore, but Arthur estimated it would be some hours yet before his command was safely landed. He turned and strode up the beach to join Stewart and the pickets, spread out along the dunes.

From the top of the highest dune close to the beach there was a clear view over the surrounding landscape.The dunes continued inland for a few hundred paces before giving way to pastureland, where the tiny figures of cows and sheep dotted the fields. A vague haze and the spires Arthur had seen earlier indicated the direction of Copenhagen.

‘Any signs of activity?’

‘No, sir,’ Stewart replied. ‘But we can be sure the men we saw will have made their report by now. I’d guess we will have some company before too long.’

Arthur nodded. ‘It would seem likely. Tell the pickets to keep their eyes open. I’m going to join the Light Company. Send a runner the moment you sight anything.’

‘Yes, sir.’

They exchanged a brief salute before Arthur turned away and strode off through the dunes towards the men blocking the opening to the beach. The air was still and hot and insects buzzed drowsily amid the tufts of grass that clung to the sandy soil. He removed his cocked hat and mopped his brow, puffing his cheeks out as the heat became decidedly uncomfortable. Even so, he infinitely preferred to fight in such fine weather rather than the bitter freezing cold he had experienced the last time he had fought on the continent. That had been in the Low Countries early in the war, when a terrible winter and incompetence had cost the British army dear and convinced Arthur that he would always look to the welfare of his men first, wherever and whenever he was called upon to fight.

Once Arthur’s brigade had secured the beach, the rest of Lord Cathcart’s army began to land, and as night fell the dunes were illuminated by hundreds of campfires built from the stunted trees that grew on the fringes of the sand. Scores of cattle and sheep had been taken from the nearest farms and slaughtered, and now were roasting over the fires. Arthur was angry over such looting, knowing full well how it would be bitterly resented by the locals and make the task of securing the Danish fleet that much more difficult. But Lord Cathcart was unmoved by his protests.

‘Come now, Sir Arthur, we are here to steal a fleet!’The commander of the British army smiled as he carved a large chunk of meat from his steak. He was entertaining his senior officers in his command tent, erected in the shelter of the dunes. It had proved a poor spot to choose as the air was thick with midges.‘I think the odd bit of beef and mutton along the way will hardly matter.’

‘Precisely, sir,’ Arthur’s immediate senior, David Baird, added. ‘Spoils of war and all that.’ The conqueror of Seringapatam turned to Arthur and wagged a finger. ‘Ah, but I was forgetting. Seems you still harbour the same scruples concerning the local people as you did back in India.’

Arthur ignored the goading and kept his attention focused on Lord Cathcart. ‘It makes little sense to antagonise the local people if we can avoid it, sir. We are a small enough force as it is, and it would be better if we maintained good relations with the people whose lands we are obliged to pass through. It is my conviction that it always pays dividends in the long run.’

‘And it costs a small fortune to pay for local produce in the short term,’ Cathcart countered. ‘Besides, it is not as if the practice of living off the land is not without precedent.Why, Napoleon’s soldiers have all but turned it into a way of life.’

‘To their detriment, sir. Now farmers and landowners conceal their stock and grain stores at the first sign of the advance of a French army. With the result that the French troops are obliged to use force to discover the location of concealed supplies, which in turn promotes a bitter hatred and thirst for revenge amongst those whose lands they pass through. In the end they will be obliged to deploy as many men to protect their communications as they have available to fight the main force of their enemy.’ Arthur shook his head. ‘I would rather not burden the British army, small as it is, with such concerns if I could avoid it.’

Lord Cathcart thought about it for a moment, as he chewed on another large piece of steak, and then nodded.‘It’s a fair point,Wellesley. But what would you have me do? Hang those who purloin the odd specimen of livestock?’

‘Yes, sir,’ Arthur replied seriously. ‘I would. The lesson would be learned soon enough.’

‘Good God, man,’ Baird protested. ‘You would value an enemy pig or a sheep above the life of a British soldier?’

‘No. I would value the safety of a man’s comrades over the life of one looter. I would value the reputation of a British army over the needs of an individual soldier.That is all.’

Baird shook his head. ‘Mad. Quite mad,’ he muttered.

As they neared the city Arthur could see that the inhabitants had made some efforts to defend themselves. A ring of simple earthworks surrounded the approaches to Copenhagen and the muzzles of cannon could be seen protruding from the embrasures of some formidable-looking redoubts. In the distance, towering above the buildings of the city, were the masts of the Danish fleet, the prize the army had been sent to seize.

There was no question of the brigade’s leading an immediate attack and Arthur ordered his men to form an extended line around the earthworks to keep watch on the enemy until Lord Cathcart and the main body of the British army arrived, with the siege train that had been landed to batter the Danes’ defences.

As Cathcart and his staff came trotting up the turnpike Arthur turned his horse and saluted.

‘What’s this, Wellesley?’ Cathcart frowned. ‘Why have we halted?’

Arthur indicated the earthworks. Flags were fluttering above each one, and the heads and shoulders of their defenders were clearly visible as they watched Arthur’s brigade deploy. ‘The Danes have been preparing for us, sir. It seems that we won’t be permitted to simply walk in and seize their fleet. I had hoped that they would see reason.’

‘Well, no one really imagined they would simply roll over for us.’ Cathcart surveyed the defences briefly. ‘Very well, gentlemen, it seems we are in for a short siege.’ He turned to his aide and dictated a brief order. ‘The army will disperse around the city and form a cordon.The engineers are to begin constructing siege batteries and approach trenches at once.Then we’ll see how long it takes them to come to their senses and offer their terms for surrender.’

As the last days of August came to an end the small British army laboured under the hot sun digging a series of trenches that zigzagged across the fields towards the enemy redoubts. By night, another relay of men went forward to work on the batteries that were to blast the city’s defences to pieces before bombarding Copenhagen itself in an effort to compel surrender. If the Danes continued to resist there would be no alternative to an assault, which would be bloody and would spare neither the Danish militia nor the civilians of the city. There was no possibility of Danish reinforcements arriving by sea, or of escape by the same means, since the warships of the Royal Navy lay anchored off the approaches to the capital, beyond the range of the guns in the forts that guarded the harbour.

Arthur watched the preparations for the siege with a growing sense of unease. The work was proceeding too slowly, to his mind, yet Lord Cathcart seemed content with the present pace and spent much of his time entertaining his officers in his command tent, which was dominated by a long dining table that had been brought ashore in his personal baggage train, together with an ample supply of wines, brandy and fine foods.

Every evening the senior officers dined with their commander, waited on by half a dozen footmen who had accompanied Lord Cathcart from Britain. And outside the sounds of picks and shovels came faintly from the direction of the siege works, together with the occasional shouted order or dull thud of a musket being discharged as the nervous sentries of both sides fired at shadows.

One night, just over a week after the British army had arrived before the city, Arthur was the last to arrive at the usual evening gathering.

‘Wellesley!’ Cathcart shouted a greeting from the head of the table. ‘Sit yourself down, man! What kept you?’

‘My apologies, sir, but I had to discipline one of my corporals for looting.’

‘Looting?’ Cathcart chuckled. ‘Hope you didn’t have the man shot! Eh?’

‘No, sir. He is to be broken back to the ranks and given the lash at dawn.’

‘Ah, well, I’m sure it will teach him a lesson,’ Cathcart concluded dismissively. ‘Anyway, eat up. My steward has managed to prepare a fine saddle of mutton, though I fancy it will have gone cold by now.’

Arthur helped himself to a few cuts of meat from the platter offered to him by one of the footmen. Major Simms, commander of the small contingent of engineers attached to the expeditionary force, was sitting opposite and Arthur leaned towards him. ‘What news, Simms? How long before the batteries are completed?’

‘Two more days, sir. Three at the most.’

Arthur nodded and was about to ask another question when General Baird, two places further along from Simms, interrupted. ‘What’s the matter, Wellesley? The Danes aren’t going anywhere. We have ’em bottled up like pickled onions.We can take as much time as necessary.’

‘I’d like to think so,’ Arthur replied evenly,‘but by now the whole of Denmark will know that we are here, not to mention the French. We need to finish the business before they can react.’

‘Pah!’ Baird shook his head. ‘You fuss so, Wellesley. But then you always did.’

Before Arthur could reply a young lieutenant entered the tent, breathless. He strode up to Lord Cathcart and leaned down to talk softly to the commander.

‘There’s trouble,’ Simms said quietly.

Lord Cathcart nodded to the lieutenant and waved him aside before tapping his wine glass with the edge of his knife.

‘Quiet, gentlemen! I pray you, be quiet.’

Once all had fallen silent and were looking in his direction Cathcart lowered his knife and cleared his throat. ‘One of our cavalry patrols has spotted a column of Danish soldiers marching on Copenhagen, no more than twenty miles away.’