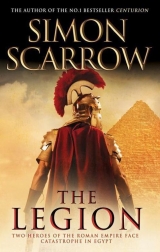

Текст книги "The Legion"

Автор книги: Simon Scarrow

Жанр:

Исторические приключения

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 28 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

Macro stopped ankle deep in the water lapping at the reeds and slipped his sword belt over his head. His fingers clawed at the fastenings of his harness. As he heaved his harness over his head and threw it aside, he heard a loud rustle in the reeds a short distance away, then a splash as a heavy body entered the water. A dark shape surged out from the reeds and made across the water at an angle towards Ajax.

At the last moment, the gladiator turned and saw the crocodile's unblinking eyes, set in its ridged tough hide. He turned and looked at Macro. 'No! NO!'

Then his head snapped forwards. His arms came up flailing, trying to beat at the monster that gripped him in its powerful jaws with sharp, tearing teeth. There was a great commotion in the water as the crocodile came up and rolled over, its light-coloured belly glistening in the last light of the day. Then it was gone. The disturbed water rippled for a moment before the Nile flowed peacefully on into the gathering dusk.

Macro watched for a moment, to be sure that Ajax was gone. His body felt numb with shock at the death of his enemy. Then there was a terrible rage that welled up from the pit of his stomach, burning his heart as he gritted his teeth, mentally cursing the gods with every resource of anger at his disposal. To have pursued Ajax for so long, and so far, only for this. Macro's fists clenched tightly and he trembled.

'Fuck… Fuck!… FUCK!'

His words echoed faintly from the far bank and then there was silence. He slowly turned away from the Nile, picked up his armour and waded on to dry ground before hurrying back to the shrine to see to his friend, Cato.

EPILOGUE

Two months later Cato climbed the path up to the imperial villa perched on the cliff on the eastern end of the island of Caprae. They had taken passage on an imperial courier packet from Alexandria, and braved the rough autumn seas to cross the Mediterranean and sail up the west coast of Italy, making for the port of Ostia on the mouth of the Tiber. When they put in at the naval base of Puteoli they were told that Emperor Claudius and the imperial secretary, Narcissus, were wintering on Caprae. Accordingly, the captain of the packet reversed course and made for the small rocky island thrusting up from the sea just off the bay of Naples. Cato had left Macro in one of the inns of the small fishing village nestling beside the harbour.

As he climbed the path, passing through checkpoints manned by wary Praetorian Guards, Cato collected his thoughts so that he could deliver a clear report to the imperial secretary. The defeat of the Nubians and the death of Ajax had brought his mission in Egypt to an end. Once the Twenty-Second Legion had returned to its base in Memphis, Cato and Macro had quit the legion and returned to Alexandria. They travelled down the Nile on a barge, Cato resting under an awning as he recovered from his wound. The Jackals' surgeon had sewn the wound up and it had taken many days before the flesh had knitted together in a jagged scar stretching across his face.

In Alexandria the governor had listened, grim-faced, as the two officers reported on the outcome of the campaign, the grievous losses suffered by the Roman army and the ravaging of the province along the upper Nile. Petronius had been angry at Cato's decision to exchange Talmis for Ajax, especially as there was no body to put on public display. But he took no action against the acting legate. Petronius announced that Cato would have to answer for his decisions before officials back in Rome, and take his punishment there. The governor had hurriedly written a preliminary report and sent it ahead of Cato for delivery to Narcissus, the Emperor's closest adviser.

Throughout the voyage home, Cato's mood had become more and more despondent. He yearned to return to Julia's side. She was waiting for him at her father's house in Rome and he could picture her, vividly, as he imagined himself stepping across the threshold and into her arms. Such thoughts were immediately soured by her reaction to the scar that now crossed his brow and cheek.

His mind was also burdened by the grievous error of judgement he had made over Hamedes. His reasoning had been faulty and an innocent man had died. Macro had spoken little of the matter and offered rough reassurance that Cato's mistake was understandable amid the chaos and bloodshed of the campaign. Cato was far less forgiving of himself.

He approached the main gate of the imperial villa at the top of the track and told the duty optio his name and rank and explained his request to see Narcissus and make his report.

'Wait here, sir,' the optio instructed and unhurriedly climbed the stairs into the villa. A cold wind was blowing over the island and gathering clouds threatened rain. To the north the hillside tumbled steeply down to the cliffs overlooking the sea and Cato stared over the bay towards the distant headland of Puteoli. A hundred or so miles further along the coast lay Ostia, and a short ride into Rome, and Julia.

'Prefect!'

Cato turned and saw the Praetorian optio beckoning to him from the top of the stairs. The guards on the gate parted to admit him. Then, at the foot of the stairs, another guard raised a hand.

'Excuse me, sir. I take it you have handed your sword and any other weapons in to the port guards?'

'Yes.'

The guardsman nodded. 'Good. Then there's one last search before you proceed, sir. Please raise your arms and stand still.'

Cato did as he was instructed and the guardsman expertly frisked his cloak, tunic and ran his fingers around the inside of Cato's belt before he stood back. 'That's it, sir.'

Cato advanced and climbed the stairs to the waiting optio, who led him through a marble portico into the atrium of the villa. The space was dominated by a large shallow pool with a tessellated image of Neptune and shoals of fish decorating the bottom. On the far side a short colonnaded hall led out on to a terrace. Through large doors to the right, Cato could hear voices, laughing and talking light-heartedly. There was a smaller opening to the left, leading down to the quarters of the slaves and lesser officials.

'This way, sir.' The optio gestured to Cato, who followed him across the atrium and down the corridor on to the terrace. A wide expanse of pink-hued marble stretched out before them and ended abruptly fifty paces away. Potted plants and trellised walkways surrounded the terrace, which afforded spectacular views across the sea towards the mainland. Cato could understand why the island had been the favourite playground of the imperial family for so many years.

There was only one other man on the terrace and he sat on a bench with his back to Cato.

'There you are, sir.' The optio halted and indicated the seated figure. 'I'll see you back at the gate, sir. To log you out.' The optio saluted and turned and marched into the villa. Cato continued across the terrace. Narcissus's thin frame was wrapped in a plain red cloak and his dark hair was threaded with grey. He glanced back as he heard Cato's footsteps and offered a smile that lacked any real warmth.

'Cato, it is good to see you again, my boy. Sit down.' He gestured towards another bench, set at an angle to the one he was seated on. A small table stood in front of the benches and a thin wisp of vapour rose from a goblet of heated wine. There was only one cup, Cato noted. This was typical of Narcissus, Cato thought, a small trick to remind him of his subordination, and put him in his place.

Cato eased himself down on to the seat indicated and Narcissus looked him over for a moment before he spoke. 'You've been wounded recently. That's quite a scar.'

Cato shrugged.

'It's been a while since we have spoken,' Narcissus continued.

'Over two years. When you sent Macro and me to spy on the governor of Syria.'

'And you both made a good job of that, as well as playing a leading role in saving Palmyra from the Parthians. Since then, you've done sterling work in Crete, and Sempronius informed me that he had sent you to find the slave rebel, Ajax.' Narcissus reached inside his cloak and pulled out a scroll. 'And now the governor of Egypt, our good friend Petronius, reports that you have resolved the matter. Well done. However, he takes you to task for letting the Nubian Prince go.' Narcissus watched Cato closely. 'Would you care to explain why you did so?'

'It was my judgement that the gladiator presented the greater threat, taking the wider picture into consideration,' Cato said firmly.

'The wider picture.' Narcissus smiled faintly. 'It seems I was right about you. You have the brains to consider the strategic situation in making your decisions.' He tossed the report on the table dismissively. 'Petronius is a fool. Your judgement was sound, young man, though you have made an enemy of Petronius, and there will be plenty in Rome who will not appreciate the nuances of your dilemma. Be that as it may, rest assured I accept what you did as the appropriate course of action, though I will not say so in public, nor will there be any official recognition of your achievement in hunting down that infernal gladiator.' Narcissus smiled apologetically before he continued. 'Then there is the difficult matter of Senator Sempronius's decision to appoint you to the rank of prefect. He did so in the name of the Emperor, I understand. However, he exceeded his authority. Of course there was something of an emergency to deal with and both the Emperor and I approve of the actions Sempronius undertook to put an end to the slave revolt in Crete and send you and Macro to hunt down the ringleaders.' Narcissus gestured towards the report. 'Now the crisis has passed and the danger is over. You have my thanks. You and your comrade, Macro.'

Cato bowed his head slightly in acknowledgement.

'However,' Narcissus continued, 'such a rapid progression through the ranks is bound to raise a few eyebrows and ruffle a few feathers, eh? Emperor Claudius is always mindful of the need not to upset those in the military, some of whom are not as loyal as they should be. The murder of his predecessor is eloquent proof of that. Which means that you present him with something of a difficulty.'

'What do you mean?'

Narcissus stared at him for a moment, and smiled. 'You're an intelligent fellow, Cato. I know I don't need to spell it out for you, but since you would derive some satisfaction from forcing me to be blunt then I will be.'

'That would be appreciated.'

'It would not be wise to confirm your promotion at present, particularly since it is your intention to return to Rome to wed that lovely daughter of Sempronius. Your presence in the capital would cause jealousy. There are plenty of other senators with proteges they are seeking to advance.'

Cato listened with an increasing sense of bitterness. This was his reward for the sacrifices made in the service of the Emperor and Rome. An expression of gratitude and, no doubt, demotion to the rank of centurion. With that would disappear his automatic elevation to the equestrian class. He could well imagine how reluctant Sempronius would be to permit his daughter to marry so far beneath her. It was true that the senator had offered some encouragement to their relationship after the siege of Palmyra, but that was a very different setting to the cut and thrust of Roman social and political life. Cato's demotion would be seen as a mark of official disfavour, even if he had the private gratitude of Narcissus and Emperor Claudius. All the plans that Cato had made for his future with Julia began to crumble in his mind. Cato cleared his throat.

'Have these proteges served Rome as well as I?'

'No, they haven't, but then Sempronius is not nearly as influential as the other senators. You see my difficulty. Trust me, I don't want to stand in the way of your promotion, and your future happiness.' He winked. 'But there are political realities that need to be addressed. That is the nature of my job. I would not be serving the Emperor well if I acted without regard for the wider picture.'

'So you will not be confirming my promotion.'

'Not for the present. Perhaps when you are a safe distance from Rome, and far from the public eye.'

'You mean that I cannot remain in Rome and take the promotion.'

Narcissus was silent for a moment, then nodded.

Cato let out a long, weary sigh. 'Very well, find me a posting, somewhere I won't embarrass you, and not so far from Rome, nor so uncomfortable, that Julia will not wish to come with me.'

Narcissus had arched his eyebrows as Cato spoke and now responded in a cold tone. 'You do not make demands of me, young man. Be clear about that. Were it not for your fine record I would punish you for speaking so bluntly. Now listen. I will confirm your promotion before the year is out, whether you are in Rome or stationed elsewhere in the Empire. I give you my word on that. And here is the reason.' Narcissus paused and looked round, as if to make sure they were not being overheard. Cato saw through the pretence at once. The security at the villa was so tight that no spy could possibly penetrate the ring of steel the Praetorian Guard formed round the Emperor's residence.

Even so, Narcissus lowered his voice.

'I have need of you and Macro. Urgent need. You recall the dealings we have had with that nest of traitors who call themselves the Liberators?'

Cato remembered them well. A shadowy conspiracy of aristocrats and their followers who wanted to do away with the line of emperors and return Rome to the days of the Republic when the senate exercised supreme power. He nodded to Narcissus.

'I remember.'

'Then know that they are active again. My spies have heard rumours of a fresh plot against the Emperor.'

'The Liberators intend to assassinate him?'

'I don't know the details, only that something is afoot. There are few men I dare trust with the knowledge. That is why I am meeting you out here, alone. I need men I can trust to investigate this further. To penetrate the heart of the conspiracy.'

Cato thought it through and smiled bitterly. 'So that's it. Either we do this for you, or you will deny me my promotion.'

'Yes.'

'And what does Macro gain from this?'

'His pick of the legions when you both return to active service. That, or perhaps the command of an auxiliary cohort.'

'And what guarantee do we have that you will keep to your side of the deal if we take on this task?'

'You have my word.'

Cato nearly laughed out loud but restrained himself in time. There was nothing to be gained from insulting the imperial secretary. Equally, there was much to be lost if he failed to accept the task being offered to him. He looked Narcissus in the eye.

'I cannot give you my answer now. I must speak with Macro first.'

'Where is he?'

'Down in the port.'

'Very well. Then go now. I'll expect to see you back here before the end of the day. Any later and I will assume that you refuse the task, and I will be obliged to find a more loyal man to carry it out. A man more worthy of promotion, if you understand my meaning.'

'Perfectly.' Cato stood up abruptly. 'I'll take my leave of you.'

'For the moment.' Narcissus nodded. 'Don't be too long, Cato. I'll be here, waiting for you,' he added with a ring of certainty that stayed with Cato all the way across the terrace, out of the villa, and down the long path back into the port as he went to find Macro.

'He's a real low, shitty, slimy, crooked piece of work, our Narcissus.' Macro shook his head. 'One of these days I'm going to take him for a nice little walk down a quiet alley and do him in.'

'Come the day,' Cato replied with feeling. He lifted the cup that Macro had poured him and glanced round the small inn. A handful of off-duty Praetorians were playing dice on a table on the far side of the room, dimly lit by the handful of oil lamps hanging from the beams. Cato lowered his voice. 'What do you think?'

'About Narcissus's offer?' Macro shrugged. 'We accept. What else can we do? The bastard has us by the balls and he knows it. Besides, if it gets me back into a legion on a permanent posting then I'm game. You too if you have any sense. How else are you going to get that promotion to prefect confirmed? I tell you, Cato, I'd do anything to get back to regular soldiering. If it takes doing one more job for Narcissus, then I'll do it.'

Cato nodded thoughtfully. His friend was right. There was no choice in the matter. Not if he wanted to marry Julia. He would have to do the bidding of the imperial secretary in order to win his promotion and rise into the ranks of the equestrian class. Only then could he present himself to Senator Sempronius as a suitable husband for his daughter. Cato reached up with his spare hand and touched his scar. He felt a stab of anxiety in his heart as he wondered how she would react when she saw him again.

Macro noticed the gesture and could not help a light chuckle.

Cato frowned at him. 'What?'

'Trust me, lad.' Macro smiled as he picked up the wine jug and reached across the table to refill Cato's cup to the brim. 'The ladies love a good scar. Makes you look more like a real man, not one of the pampered dandies that strut around the forum in Rome. So, let's have a toast. Death to the Emperor's enemies, and here's to the rewards that are long overdue to us both.'

Cato nodded as he tapped his cup against Macro's. 'I'll drink to that, my friend.'

AUTHOR'S NOTE

The Roman province of Egypt was one of the most vital assets of the empire. Rome had been interested in Egypt long before Octavian (who later adopted the title of Augustus) annexed Egypt following the suicide of Cleopatra – the last of the dynasty established by Ptolemy subsequent to the carve-up of Alexander the Great's conquests. Thanks to the regular floods of the Nile, the production of wheat was prodigious. Better still, the kingdom stood at the crossroads of trade between the civilisations of the Mediterranean and the east. The wealth accrued from agriculture and trade made Alexandria the most prosperous and populous city in the world after Rome.

So it was only natural that successive emperors would jealously guard the jewel in the crown of Rome. Unlike other provinces, Egypt was the personal domain of the emperor, who appointed a prefect to govern the province in his name. Members of the senatorial class, and even those from the lower rank of the equestrians, were strictly prohibited from entering Egypt without the express permission of the emperor. Not that the febrile brew of ethnicities in Alexandria needed outside agents to provoke it into violence. One of the recurring features of the history of the province is the frequent outbreak of riots and street-fighting between the Greeks, Jews and Egyptians who inhabited Alexandria and vexed the patience of the Roman governors.

Roman rule of Egypt was based on one overriding purpose: to extract as much wealth from the province as possible. Consequently, the administrative system was run extremely efficiently to maximise tax income, and the people of Egypt were taxed to the hilt. Much of the burden rested on the middle class of the province – the traditional and easy target of tax officials then and now. As a consequence, the unlucky taxpayers eventually succumbed to debt, and the long term decline of Egypt began.

The native Egyptians had already resisted the earlier imposition of Greek culture by the Ptolemies, and the Romans never managed to persuade the natives to buy into the Roman way. Latin was the language of oppression and, outside of Alexandria and the largest cities and towns, life carried on pretty much as it had under the pharaohs. Even today, many of those living along the banks of the upper Nile still live in the same mud-brick houses as their forbears and harvest their crops by hand.

Aside from the heavy hand of their Roman masters, the local people also endured frequent raids and small invasions by Nubians and Ethiopians across the frontier south of modern Aswan. The Roman outposts either side of the narrow strip of inhabitable land on both sides of the Nile were easily overcome or circumvented, and plunder easy to come by. The legions of Rome were always stretched thinly around the thousands of miles of frontier that protected the empire. It was no different in Egypt. The three legions that Augustus had stationed there were soon reduced to two, one of which was dispersed to various postings across Egypt. The balance of troops available to the governor was made up of auxiliary cohorts. Under the close watch of the Emperor, the governor had to ensure that the wheat and tax continued to flow to Rome, while managing barely adequate forces to maintain order and defend the frontier – a truly unenviable job.

As ever, I have made sure that I walked the ground on which the novel is set. I can vouch for the discomfort of those marshes in the delta, and the searing heat of the upper Nile! The ancient ruins are also well worth a visit and I could not help but be in awe of the civilisation that had created such vast monuments long before an obscure settlement on the banks of the Tiber even came into existence. For readers who want to experience Egypt for themselves I would heartily recommend a trip to Luxor (Diospolis Magna). Many of the locations mentioned in the novel are still there and, with a little imagination, can be viewed just as Macro and Cato would have seen them.