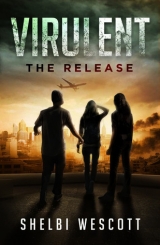

Текст книги "The Release"

Автор книги: Shelbi Wescott

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 4 (всего у книги 16 страниц)

CHAPTER FIVE

“Oh my goodness,” Lucy said and she walked forward toward her English teacher. But before she could maneuver herself closer, a burly Health teacher, still wearing a whistle around his stump-like neck, swooped forward with his hands out.

“No students in this area. Back to your row please,” the man said, swollen with self-importance.

With no energy to protest, Lucy turned on her heels and turned her back to Mrs. Johnston, who probably had no memory that Lucy wasn’t even supposed to be at school at all. Pulling her phone from her pocket, Lucy had no new messages. The time broadcast itself in large block numbers at the top of her screen. Their initial domestic flight to the East Coast would be in the air within the hour. Lucy entertained the notion in the back of her mind that sunny island weather and fruity drinks in coconut cups were in her future. She clung to those images as a last thread of hope that anything familiar could be salvaged. Halfway down the aisle, Lucy found a clearing of seats and wedged her way to the middle of the row, plopping herself down.

Lucy watched as their principal Spencer took the stage. He sauntered forward, leading with his forehead, one hand shoved into the pocket of his pants, the other one holding a wireless microphone. A pimply theater tech student assumed command of the follow spotlight and flooded the stage with a bright white light. The principal blinked into the orb and then blew into the mouthpiece of the microphone, a whoosh of sound shrieked across the seats. Like sheep, those standing, chatting, and crying filed into empty rows, all eager to hear the news, to hear the plan.

There wasn’t an ounce of compassion on their leader’s face as he stared down at them with flat eyes, gnawing on the inside of his right cheek.

“Sit down,” he commanded, his mouth close to the microphone. “Find a seat and sit down.” He pointed to the group of sobbing and cuddling kids near the front rows, so engaged in their own dialoguing that they had ignored his initial call to disband. “Get up and sit in a seat. You have sixty-seconds,” he barked at them. When it was clear they had tuned him out, he motioned angrily toward the school’s Resource Officer, a city of Portland policeman, his cop uniform bright and clean and his badge shiny.

The officer nodded and with quick precision, stalked forward and grabbed the closest boy to him by his back collar and tossed him backward like a ragdoll. Then he began to pull each of the students apart by force, throwing them toward seats, stepping around their huddled masses without regard for toes and fingers or long-braided hair. Only then did the kids begin to migrate toward the red cushioned seats, nursing their sore arms where the officer unceremoniously pulled them to their feet. A young girl began to wail and a boy, who had seconds earlier been cradling her, hushed her.

“Shut up,” their fearless leader hissed, his voice echoing up the aisles.

No one dared to breathe. The officer crossed his arms and glared back out at the students, now huddled like potato bugs against armrests and seatbacks, all curled up into balls of arms and legs and messy hair.

Principal Spencer cleared his throat into the microphone. His speech started in a soft voice, and despite the microphone, some auditorium congregants leaned in to hear. While he spoke, he paced up and down the length of the stage. The follow spot moved with him, bouncing slightly and catching the dust particles floating like snow across the auditorium.

“You will follow orders. You will follow orders the first time we ask. There is no room for argument, for disagreement. There is no protocol for this and we are not writing futile referrals. We cannot simply call your parents to take you home,” he said with disgust instead of empathy. “In order to function, we will operate with absolute obedience. And understand that the decisions I am making on behalf of the student body and the staff is for our mutual benefit. Whether or not you agree is a non-issue. My goal is protecting the people in this building.” He paused.

Someone raised a shaky hand, but Spencer didn’t notice.

Then a teacher called from the back, Lucy thought the same power tripping man with the whistle: “No questions.”

And the student lowered the hand with resignation.

Spencer continued. “As you are aware, lockdown is in effect. We will open the outside doors for no one. No one out. Absolutely no one in. Am I clear?” he asked rhetorically.

Pockets of protest erupted around the auditorium, but teachers began to move toward the noise—silencing people and demanding attention.

“The major threat is outside these walls. Until we know more, I will not needlessly endanger you,” he said.

“Himself,” a boy behind Lucy said in a quiet non-whisper. “He will not needlessly endanger himself.

Lucy turned and saw Grant Trotter sitting behind her; his sandy blonde hair a mess of tangles, with bangs falling into his eyes. He half-smiled at Lucy—the facial equivalent of a shrug. And she acknowledged him with a nod and a sad smile-like response.

As Spencer droned on about expectations and rule following during this “fragile moment in our lives,” Grant’s body fell forward and his head hit against the back of the seat where Lucy was sitting. She could feel the pressure against her back, the bump of flesh hitting plastic. She turned again, her arms going rubbery, as she braced herself for the worst. She peered down at him and resisted the urge to reach out and grab his shoulder while she looked intently for the rise and fall of breath.

“Hey,” she whispered, leaning toward him, but still keeping her distance. “Hey…are you okay?”

Grant’s head snapped up, his eyes red, bloodshot, but his cheeks pink. He smiled an actual smile, one small dimple forming in the center of his cheek. “That’s sweet,” he said to her. “You thought I died.”

“Yes,” Lucy replied. “Don’t say it like that. Don’t say it like it’s strange that I would think that.” She blushed out of embarrassment.

“I feel fine,” he said. Then he shook his head. “No. I don’t. I don’t feel fine. But I feel alive. Very much alive.”

Lucy wondered if she felt alive. Certainly she could feel her heart, her heavy limbs; her head ached right behind her eyes and her stomach growled. She exhibited all the signs of a living human being, but something wasn’t right. Were the crying kids in the corner more alive than she was? Because Lucy couldn’t bring herself to sob or yell—instead, she felt lost, trapped in perpetual murkiness. Fear hovered just below the surface, but it hadn’t created a stronghold yet, hadn’t clawed its way in and nested itself among the hunger and the hope.

“I guess I don’t feel alive,” she said. “I don’t feel real.” Lucy didn’t even know if that made sense, and after saying it out loud, she felt foolish. Grant didn’t respond, only looked at her with his dark brown eyes in an assessing way.

She turned away from his gaze.

“Numb,” he answered to the back of her head. “You feel numb.”

Lucy couldn’t even bring herself to nod.

Two rows in front of her, a boy leaned in to kiss his girlfriend on the cheek. A sudden sloppy decision, uncoordinated, and initially unnoticed. The girlfriend turned to him as he leaned in and then screamed loudly, a mixture of complete alarm and blind disgust as blood rolled down his cheeks. Dripping from the corners of his eyes, like a stream of tears, staining his shirt with growing circles of crimson. Even under the dull auditorium lights, Lucy could tell his skin was fading from pink to a pale, grass-stain green.

“I’m just…I’m a little queasy,” Lucy heard him mumble to the girl as she scrambled away, her head turning in every direction.

“Help him! Help him!” The girl shouted, scooting backward as he reached for her, on his knees now, stuck between the chair and the row in front of him, cupping his hands around his mouth and heaving into them. Her squealing interrupted Principal Spencer’s continuous droning about the consequences of insubordination.

It was the first time she had seen someone fall victim to the virus, and the instantaneous nature of this silent killer filled her with such dread that she buried her face in her hands—pleading with herself not to look. How could it work like that? One minute he was fine, just a teenage boy sitting next to his girlfriend, hoping, even among death and destruction, for a kiss, a sign of unwavering affection. And the next minute he was sucking for air, losing control of his bodily functions, spilling blood in pools like ink stains on the carpeted floor.

Teachers flew in from the corners and launched themselves over seats and into the row. Each one donned rubber gloves, pulling them from pockets and snapping them on in haste. They approached him with speed, but without worry. They would go to him, lean him back, exit others away from his body, but their faces told the truth they couldn’t say aloud: This boy is gone. There is nothing we can do for him.

This had been their entire morning, and this student was just one of many. Already they had adjusted, adapted, and molded themselves into their new roles. Earlier their focus might have been mitosis-labs and Steinbeck-essays, parent-emails, and Special-Ed-meetings, but now they were body-collectors and lockout-supervisors. How easy it all became the new normal.

“Let’s move him back,” a large math teacher told the others, his belly exposed, bursting through bulging buttons. After some maneuvering around the row, a male teacher and a male counselor grabbed the lifeless boy and paraded down the aisle. Lucy only then noticed that someone in that madness had been generous enough to close his eyes. Or maybe he had closed his eyes in the end—she could only guess as she had kept her own eyes trained away from the boy in his final moments. Working together, the adults hoisted the body on the stage, and then carried him off behind the set. It was as if it were all a giant play and the boy was an actor, the charade nothing more than directions in a script.

“Where are they taking him?” Lucy asked to Grant, not bothering to turn around, just leaning her head back.

“They’ve been taking everyone to the dressing rooms, I think,” he replied. “Confining the bodies for the uprising.”

Lucy swiftly turned. “What?”

“Zombies? When everyone comes back as zombies?”

“This can’t possibly be a joke to you. Is this a joke to you?” Lucy asked. “That boy died. I just watched that boy die!”

Grant ran his right hand through his hair, mussing it up near the crown. “First time you’ve watched someone...” he made a face as he trailed off. “Yeah, well, you’ll get used to it. Watching it all morning will make you…what did we say? Numb. Right.”

Lucy bit her lip. “This morning I was at home.” She wanted to explain, but the thought of her mom—her frantic, unexplained text—and of Harper with her lopsided pigtails, her brothers and their own unique smells and smiles, was too much and she couldn’t go on. There was no place she would rather be than with her family. She couldn’t bear the thought of them suffering. In her mind, everyone was still packing for the trip and her mother was still pacing with her clipboard, irate at Lucy’s thoughtless tardiness. Ethan was furtively kissing Anna goodbye while Galen argued that his lucky-never-been-washed Beatles sweatshirt had a place among the lavender infused suitcases. The twins were off to run reconnaissance for each other while sneaking the plane snacks.

This is how they were right now.

At her house.

Safely supported in a bubble protecting them from the chaos she heard—the gunshots, the loud crashes, and foundation rocking, earth shattering booms. Whatever was happening outside of this school was not happening at her house because it could not be any other way. It just simply could not.

“I wasn’t trying to joke,” he replied with a sigh. “I’m well-versed in zombies. It starts with some unknown sickness that wipes out the population and ends with the walking dead.” He paused, waiting for Lucy to chime in. She just looked at him, softened, but incredulous. “I’ve been watching everyone at school fall all morning,” he told her, leaning closer, eager to share. “Spanish class, first period. Mary...Mary?” he paused, waiting to see if Lucy knew the name.

“Bishop? I know her.”

“We were watching the news. Just glued to the news, right? Senora Cochran was just sobbing and we were all just...sitting there...and Mary gets up and says she doesn’t feel so good and can she go to the bathroom.” Grant pauses and closes his eyes. “I’d never seen anyone die before. Before that moment, you know? It was so fast. We didn’t even get up out of our seats. We thought she had fainted. Or that she was just being stupid and dramatic. Some people actually laughed. At first. They laughed at first.”

Lucy didn’t know what to say. She looked down to the back of the seat. “I’m really scared,” she admitted.

While it could have seemed like a non-sequitur comment, Grant didn’t miss a beat. “Yeah, I’m terrified too.”

The body-collection team reappeared empty-handed, and Spencer demanded the attention back as he tried to calm the escalating conversations through the microphone.

“You will be escorted by a teacher into their classroom,” Principal Spencer said. “You will not be allowed to leave the classroom until we have a better understanding of what we’re facing or until we have support from local law enforcement.” Groups began to talk with rushed anxiety. “Remain seated until a teacher comes to collect you.”

Voices of dissent carried through the auditorium.

“Remain seated!” Spencer instructed again straight into the microphone.

But the panic was escalating. A teacher made his way up on the stage and whispered into Spencer’s ear and as he did, a boy, a tenth grader, slipped up onto the stage and crawled over to him. It was clear to everyone that the boy was ill. He vomited near the edge of the stage, but despite the fact that the virus was taking hold, he kept trying to work his way to Spencer. By the time the student had reached the principal’s pant leg, he was already starting to shake.

Lucy could hear Spencer scream to get the boy away from him.

“Remove him. He’s infected! Remove him now!” came the screams, increasing in intensity as the child moved closer to death. But the boy didn’t relent. He kept a grip on Spencer’s pants, keeping the principal rooted to the ground even as he tried to tug and pull himself away.

Then they all saw it.

And the auditorium gasped in unison when Principal Spencer, in one swift motion, kicked the boy with his free leg. It was a solid, well-placed swipe at the dying boy’s jaw, and the boy’s head lopped to the side after impact. Whether or not the child was already close to death did not matter, Spencer’s kick had demolished him, and his head flung backward and then hit the floor with a sickening thud.

Everyone stopped and watched as the man looked out over the crowd, his face contorted in a mixture of alarm and growing defensiveness.

“Get it out of here!” he cried, but no one moved. “Students…listen…your lives are in danger. And you will follow my directions or suffer the consequences.”

Lucy stiffened and shifted uncomfortably in her seat.

He called the names of some of his cronies—other administrators with whom he could form an alliance of power and hatred. But none of them stood forward immediately, and for one long moment, Spencer was left standing alone, the dead boy at his feet. He dropped the microphone to the stage, and it caused a loud crash that reverberated through the speakers. Several people threw their hands up over their ears. All around the auditorium people grumbled their resignation or agitation.

Without amplification, Spencer yelled, “Follow the orders! Just follow my orders.” And then, as he noticed other children coughing and slumping, reaching out to him for assistance and reassurance, he shot down the stairs of the stage and flung the auditorium doors open wide, running quickly away from the kids with whom he was instructed to protect.

For a second everyone looked at each other with confusion. But then the teachers moved into position—determined to follow the protocol even in the absence of their leader. Some walked swiftly, stern faced, and eager to take charge. It was not surprising that even amidst the turmoil outside, some of the adults found comfort in supervision. They could push aside their own fear and assuage their growing worry with a false sense of control. Lucy closed her eyes and sent up a prayer, a hope, that she would not get stuck with some adult with a superiority complex.

When her eyes fluttered open, it was Mrs. Johnston standing next to her. Blonde hair loose in wavy curls that fell to her shoulders; she was playing with a silver chain around her neck, twisting it around the fingers of her right hand, dropping it, twisting it again. Her normally bright skin was dull and pale, and a dried glob of mascara had latched itself near her cheekbone. With a shaky hand, she ran her hand over a section of five rows.

“You all. From here to here. Follow me,” she called to them, but her voice was small, absent of authority.

Ten of them, Grant included, rose from the chairs—the seats swung backward with repetitive whack-whack-whacks until they slowed to a stop. Lucy grabbed Ethan’s backpack, still weighted down with the textbook and binder, swung it high on her shoulder and stood beside her English teacher. Mrs. Johnston reached out as if to pat Lucy on the arm, then dropped her hand, a shuddering sigh escaping before she turned and began to walk down the aisle, each of the kids in her charge falling into single-file line, the old elementary habit returning.

“Mrs. Johnston?” Lucy asked when they had left the auditorium and were making their way back up the long hallway toward the English hall. The other kids from the auditorium disappeared into other hallways, other classrooms, out of sight. “Mrs. Johnston?”

“Yes...Lucy,” she answered, breathless, slowing her pace, dropping back to walk side-by-side.

“How long can they keep us here?”

“They can keep me until the end of my contract hours and then I’m gone,” Mrs. Johnston responded through clenched teeth. “I have a family.”

“But what about us? They can’t keep us here. Right? They can’t force us to stay against our will.”

Mrs. Johnson hung her head. “You don’t understand. I have to go. I have to go home. But principal Spencer isn’t wrong...it is safer in this building.” She glanced back at the ten students following her as each one sped up to walk in a huddle, hungry for news.

Grant leaned closer, “Before...when we were watching the television? Someone reported that military planes were flying over cities and dropping a green gas into heavily populated areas. Is that true?”

“I don’t know anything,” she said and put her hands up in surrender. “No one knows anything.” Her heels clipped on the tile, picking up her pace to a brisk walk.

“Who attacked us?” said a sophomore girl toward the back of the group—she clutched her bright red leather purse in front of her like a shield, knuckles turning white. “Do they know who?”

But Mrs. Johnston had decided she was done answering questions, so she did not acknowledge the growing bombardment of worries. As each student lobbed up a theory or a snippet of news, she just walked faster, until the whole group shuffled along at a near-run to keep up with her. It was clear that she was taking the group to her own classroom, steering them back through the trail of bodies that Lucy had traversed earlier. As they hit the long corridor littered with the dead, some of the students slowed. This carnage was new to them, and some of these people were their friends. The sophomore girl closed her eyes tight and stopped moving entirely. She just stood there in the middle of the hallway, her red purse covering her stomach, her feet shoulder width apart, unmoving. She kept her eyes scrunched closed, her mouth grimacing, her teeth showing.

Lucy recognized a boy named Clayton from her biology class among their small group. He called down the hallway. “Mrs. Johnston! Wait up!” Then he walked back and stood next to the girl, touching her purse and gently leading her forward.

“I won’t. I won’t go,” she said and stiffened her body even more.

But Clayton was patient. “I’ll lead you. But you have to take my hand. Like those trust walks, right?” But she wouldn’t lift her hand up, wouldn’t take it off the purse, and wouldn’t open her eyes or budge.

By that time, Mrs. Johnston had noticed half the group wasn’t keeping up with her quickened pace. She stopped and turned, eyes red, new rivulets of black running down her cheeks.

Then Lucy felt it.

Not the quick buzz-buzz-buzz of a text.

But the long and sustained buzzzzzz of an incoming phone call.

At first she thought she was imagining it—that all of her hoping and daydreaming had turned into an auditory hallucination accompanied by phantom vibrations. Frantic, she dug her hand into her pocket and retrieved her phone. The phone slipped, but she caught it against her jeans, and her sweaty fingers attempted to grab ahold.

As the other students noticed the action, each one looked to their own phones, scampering to send a text, place a call. Hope. Lucy saw it in an instant in all of their faces. Technology was back, so there was hope.

Without even looking, Lucy answered. A lump rose in her throat as she waited for her mom’s voice to hit her ear. Please just tell me everyone is okay, she thought. Please, Mommy, please.

She pleaded for the news to be good.

“Lula? Lula? Are you there? Are you there?” The voice was high-pitched, rushed, and jumbled. Voices swirled in the background and there was a distinct gunshot again—it was louder in the phone, but the blast echoed in the school too.

From outside, this call was from somewhere right outside.

Salem.

“Sal? Sal?” Lucy answered. “Where are you?”

“I’m at the school,” Salem said and Lucy hopped up and down when she heard the news.

“Thank God! Sal, I’m here too! It’s a long story…but I’m inside Pacific right now. No one can get out, Salem. They have everyone locked inside! It’s a total nightmare.”

“Lucy, listen. I’m outside. I’m right outside the cafeteria, by the big doors. We can’t get in Lucy. No one can get in!”

“No one can get out!” Lucy said overlapping. Then she paused and processed their conflicting wishes.

Another gunshot. Again, she could hear it both in the phone and in her ear. There was a slight delay between one and the other—a small disconnect, as if two shots were ringing out upon each other.

“Salem? What the hell is going on?”

“They’re trying to shoot the card lock off. They’re trying to shoot the glass. I tried to tell them it’s bulletproof, but it’s madness here. God, Lucy, help me! Help me, please!” Salem’s voice was beyond begging, her sobs shot through the phone in short bursts of pure panic.

“I’m coming! Okay, okay! I’m coming,” Lucy yelled into the mouthpiece and, with only a quick look to Mrs. Johnston and the rest of the group—all of whom had frozen to listen to her conversation—she took off running back in the other direction, her phone still pressed to her ear, her backpack rising and falling as she ran, the gravity of it threatening to pull her to the ground. She didn’t know what she would do when she got there, and it only occurred to her that she was running toward gunfire as the cafeteria doors came into view.

“I’m almost there, Sal. I’m almost there,” she said into her phone.

“Lula. You have to get me inside the school. You have to get me inside the school right now.”