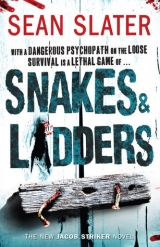

Текст книги "Snakes and ladders"

Автор книги: Sean Slater

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 12 (всего у книги 29 страниц)

Thirty-Eight

The moment the receptionist allowed them inside Dr Ostermann’s office and shut the door behind them, Felicia looked over at him and a grin spread her lips.

‘That was terrible,’ she said.

Striker just shrugged. ‘I know, and believe me I’m not proud of it, but we had no choice. We needed to get in here before Ostermann got back. We need to know who this Billy guy is. It’s as simple as that.’ He looked at his watch and saw that it was ten-fifty now. ‘What time she say his session ended?’

‘Eleven – and that’s if he doesn’t finish early.’

Striker frowned at that. Ten minutes wasn’t a lot of time. He looked around the room. To his surprise, the office was fairly barren. He’d expected to see medical diplomas hung on every wall. Plaques and certificates and awards. Maybe some pamphlets for the EvenHealth programme. A row of books, at the very least.

But there was none of that.

All that occupied the office was a large oak cabinet in the far corner, a big sturdy wooden desk, and a pair of comfortablelooking leather chairs sitting opposite the desk.

On the walls hung nothing but standard pictures. A sailor looking out over the sea; a little boy at the doctor’s office; and a Native Indian-style wolf head. Aside from this and a few plants decorating the room, there was nothing of interest. No shelves, no books at all.

Striker moved over to the desk. He tried to open the drawers but they were all locked. On it was nothing but an ink blotter, a computer and a keyboard with mouse. The computer screen was blank, and when Striker moved the mouse, the logon screen appeared.

‘Needs a password,’ Felicia said.

‘EvenHealth?’ he asked.

‘Lots of luck,’ she said.

He knew she was right, and didn’t even venture to guess. Instead, he moved over to the cabinet on the far side of the room and opened the doors. Inside was a small TV set with built-in DVD player. A Samsung. On the shelf below was a row of DVDs, each one with a name on the side. Striker searched for any with the names Larisa Logan or Mandy Gill, but found none. Instead, he found one labelled Billy Stephen Mercury. And in brackets were the words: Kuwait. Afghanistan. PTSD.

PTSD – Post-traumatic Stress Disorder.

He turned and looked at Felicia. ‘Our Billy?’

‘Write down the details. Hurry. Before Ostermann gets back.’

‘I’ll do more than that,’ he said. He flicked on the TV and grabbed the DVD case. He opened it, slid out the disc, and slipped it into the tray.

Felicia gave him a nervous look. ‘Jacob, what are you doing?’

‘Just watch the door.’

‘Watch the door? It’s five feet away from you.’

‘Then just stand by it and listen. Let me know if you hear him coming.’

‘Ostermann’s due back any minute. And what if I don’t hear him? What then?’

Striker smiled. ‘Then sit back and pull up a chair because there’s gonna be some fireworks.’ He leaned forward and pressed Play, and the disc loaded.

Seconds later, the screen came to life.

The video quality was surprisingly good, damn near high def, though the sound was slightly muffled. The camera was angled from the left side, with Dr Erich Ostermann sitting opposite a young man. Between them was an ordinary wood desk with nothing on it.

A different room.

Striker took note of the walls – there was absolutely nothing on them – and then of the male being interviewed. He was Caucasian, and terribly thin, emaciated, yet he looked wiry, strong. He could have been in his late twenties or early thirties – it was hard to tell. His hair was dark brown, but greying, and the stubble on his face was almost entirely white.

‘He looks young, but old,’ Felicia noted.

Striker made no reply. He just studied the patient on the feed.

The skin of Billy Mercury’s face had few wrinkles, except around his eyes, where there were many. The man looked tired, as if he hadn’t slept well in years, and the paleness of his skin amplified this look. Perspiration dampened his skin, and when he breathed, his chest rose and fell heavily, unevenly, as if he were hyperventilating.

Dr Ostermann sat in his chair, then turned it slightly to the left to allow the camera a better angle for recording. He stated the date and time of the interview – it was just two weeks ago – and then briefly introduced himself, humbly giving the most basic of his credentials.

Last of all, he introduced his patient.

‘And this person opposite me is Billy Stephen Mercury,’ Dr Ostermann said to the camera. ‘Billy is a soldier who spent time in Afghanistan. First Class with the 7th Regiment. Coming back from the war, Billy suffered from extreme depression and night terrors, making it difficult to sleep and cope with the normal activities of daily life. He was subsequently diagnosed with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and has been doing sessions with me here and at EvenHealth for the last seven months. Billy is making significant progress, and if all goes well, will be returning to his life outside the facility very soon. His independence is our first and foremost priority.’

Striker studied everything on the screen. During the entire introduction, Billy Mercury had said nothing. He just sat there and barely moved, staring at nothing in the room. His body trembled. His skin sweated. His breath came in fast and uneven gulps of air.

‘So Billy,’ Dr Ostermann continued. ‘Last session, we ended with you speaking of your time in Afghanistan. More specifically, the enemy engagements. You were talking specifically about Kandahar. This was a very bad time for you, as I understand.’

Dr Ostermann paused to give Billy Mercury a chance to speak; when the patient didn’t, Dr Ostermann continued.

‘When we last left off, you were telling me how one of your company – a Colonel Dylan – was killed by a roadside attack and how you had been separated from your party in the back roads of the town. Would you care to continue the story?’

For a long moment, Billy Mercury said nothing. He just sat there, shaking and sweating, letting the silence envelop them. Then, with a start, he came to life. He began looking all around the room, his eyes shifting rapidly, as if seeing things in the room that no one else could see.

‘They were everywhere,’ he finally said. ‘In the streets of the village. In the doorways of the homes and in the open markets and in all the crevices . . . but in the shadows. Always in the shadows.’

‘And this was . . .’

‘The enemy.’

‘The resistance soldiers?’ Dr Ostermann asked. ‘The people of the town? Who exactly were they, Billy?’

‘Who?’ he asked, and suddenly he let out a high-pitched laugh that turned into a cry. ‘What is more important.’

Dr Ostermann’s face tensed, though only for an instant. ‘Billy, we’ve been over this before—’

‘I saw them over there. In Farah and Herat and Kandahar. I saw them many times. They were everywhere. Pretending to be soldiers. And citizens. Children, even. They lived in the darkness. Came out of the shadows. They’re born in the blackness, made from blackness. It seeps right out of their eyes, their mouths.’

‘Billy—’

‘Made of fucking hellfire!’

‘Billy, we’ve discussed this before. It’s psychosis, it’s delusions—’

‘NO! You don’t understand, Doctor. You weren’t there, so you can’t know. It’s not like here. It’s another world. Another place. They can live there, they can grow. And they’re getting stronger. They’ll be coming here soon. They’ll get inside the clinic. Come for me. Come for you! Come for everyone!’

Dr Ostermann’s face took on a disappointed look, but he said nothing. He just stood up slowly from his chair and shook his head.

‘I think we need to revisit the medications,’ he said.

‘NO!’ Billy said. ‘You don’t understand. You think I’m crazy. But you don’t know. I can hear them at night, whispering. Always whispering. They’re coming for me. For us all. You can’t fucking KNOW!’

Dr Ostermann reached for the door, and Billy suddenly jumped up. He up-ended the desk, grabbed hold of the doctor, and Dr Ostermann began to scream for security. Within seconds, three large men dressed in white pants and shirts burst into the room. They grabbed Billy Mercury, but he fought them. Raked his nails down the first man’s face; hammered the second orderly with a vicious punch to the throat.

‘Daemons!’ he screamed. ‘Fucking daemons – THEY’LL GET US ALL!’

Thirty-Nine

Striker stood in the centre of the room, mesmerized by the video footage before him. The man on the screen was completely delusional. And dangerous. Striker could feel it. He was so engrossed in the interview that it took him a few seconds to hear Felicia’s whispered warning from beside the door.

‘. . . coming, Jacob. Dr Ostermann – he’s coming!’

Striker finally clued in. He hit the Stop button on the DVD player, powered off the television set, and walked back across the room. He was just nearing Felicia when the door opened and Dr Ostermann walked into the office.

The doctor gave them both a careful look, then nodded. ‘Detectives. Good to see both of you again, though rather unexpected, I must say.’

Felicia said, ‘It’s good to see you as well, Doctor.’

Striker felt less inclined for the bullshit. ‘We said we’d be in contact, Dr Ostermann. So this is anything but unexpected. In fact, the way I remember it, you were supposed to call us.’

Dr Ostermann’s face took on a faraway look, and he nodded. ‘Oh yes. Yes, I believe that is correct. And I planned on doing so. But it has been a very busy morning indeed.’

He stepped further into the room and closed the door behind him, locking out the receptionist and patients. In his hands was a dark green file folder with some black writing on the tab.

Striker could not make it out.

Dr Ostermann walked over to his desk, slid open the drawer, and dropped the file inside. As he turned to face them, closing the drawer, his eyes caught the open cabinet, and he stopped what he was doing and just stared at it. Without saying a word, he walked across the room, stopped facing the DVD player, and looked at the DVDs. He picked up the empty case marked Billy Mercury and opened it. When he saw no DVD inside, he turned to face them and the skin of his cheeks was slightly pink.

‘Were you . . . watching this?’

Felicia said nothing.

Striker stepped forward. ‘Stop answering my questions with ones of your own, Doctor.’

Dr Ostermann’s face turned from pink to red, so deep that even the top of his thinning hair showed blush. The contrast made his eyes look like green ice. ‘I beg your pardon, Detective Striker?’

‘Beg nothing. You heard what I said.’

Dr Ostermann snapped the DVD case closed and put it away. ‘There was never any question asked of me.’

‘It was implied.’ Striker stepped up to the desk so that he was within arm’s reach of the man. ‘I didn’t come all the way from Vancouver to Coquitlam for a social visit, Doctor. And I think you know that. You were supposed to call us this morning; you didn’t.’

‘I just told you, it’s been a very busy morning. I’ve had many things on my mind. Many patients to tend to. They come first.’

Striker steeled his voice. ‘I wish I could say the same for Mandy Gill.’

Dr Ostermann froze, and silence filled the room. Striker was happy to wait it out. He gave Felicia a quick but casual glance to make sure she kept quiet, too.

He wanted Ostermann to sweat on this one.

‘The reason I haven’t called back,’ the doctor finally explained, ‘is because I haven’t yet been able to reach my patient. And I’m not about to give out this person’s personal and private information until such time that I do. It’s as simple as that.’

Striker nodded. ‘That’s fine then, Doctor. And here’s my response to you: you can either fess up this guy’s name, or I will head down to the court house, bang up a warrant, and then come out here and take your whole office and Records Section apart.’

Dr Ostermann’s face paled. ‘No judge would allow that.’

‘Actually, I think they would. And think of how the media would eat that one up: “Dr Ostermann, psychiatrist for the poor, refuses to help the Vancouver Police Department’s investigation on the possible murder of a poor mentally ill woman – a patient of the EvenHealth programme, no less.” Man, I can just see the headlines now.’ He looked back at Felicia and smiled. ‘Or we could just seize any files and be done with it.’

Dr Ostermann stepped back. ‘Seize my files? Under what grounds?’

‘Exigent circumstances,’ Felicia said.

Striker nodded. ‘Exactly. You have a patient who we think might have been murdered – not committed suicide, as previously thought – and there’s a connection to one of your other patients. A man who might also pose an extreme risk to others. That’s exigent enough for me. Hell, it’s one of our prime duties as police officers – Protection of Life.’

‘That would never stand up in court.’

Striker shrugged. ‘Maybe not. But I’m more than willing to fight that a year or two down the road – after I seize your files here and at EvenHealth.’

‘EvenHealth?’

Felicia stepped forward. ‘Work with us, Doctor.’

Dr Ostermann’s face paled even more and he leaned back against the desk. ‘I wonder. What would your Inspector say to all this? Or perhaps your Deputy Chief. He and I know each other, you know. I am a well-known contributor to the Police Mutual Benevolent Association, and have been for many years.’

Striker grinned. ‘The chief would care as much as the media would if, say, this thing got leaked and they learned we were seizing your patients’ files.’

Dr Ostermann said no more, and a distant, horrified look filled his eyes, as if he was picturing the nightmare that could unfold.

Striker gave Felicia a quick glance, saw the concern in her eyes, and knew she would give it to him later. But for now, he had the upper hand, and he knew it. He met Dr Ostermann’s stare and said, ‘So what’s it going to be, Doctor? Are we going to help each other out, or not? We are on the same team, after all, right?’

Dr Ostermann’s posture sagged and he let out a tight breath. ‘Same team. Yes. Yes, of course.’ He moved gingerly around his desk and sat down in the high-backed leather chair. He opened the drawer. Pulled out the green file folder he had been carrying when he entered the room. He flipped wearily through the pages, then dropped the whole thing on the desktop.

‘His name is Billy Stephen Mercury,’ he finally confessed. ‘As I am sure you well know. He has been a patient of mine for quite some time now, ever since his return from overseas.’ His eyes flitted to the DVD player, then back at Striker. ‘We are off the record here?’

‘Of course.’

He nodded. ‘Billy was a soldier, suffering badly. Post-traumatic Stress Disorder, just like the DVD says. Barely sleeping. And self-medicating to deal with the pain. Delusional. One step away from being psychotic. When he was here, he was a very hard patient to deal with at times.’

Felicia asked, ‘When he was here?’

‘Yes, when. The medications helped greatly. And Billy did progress. He was released because of this – as part of the outpatient programme. And for a while, he was doing quite well on his own. We always kept tabs on him, of course. He had to see one of our psychiatrists regularly. But that was mostly to reassess the medications and make sure they were working. Make sure he was taking them as prescribed. The majority of his healing came through one of the EvenHealth programmes.’

‘Which particular programme?’

‘We called it SILC – Social Independence and Life Coping skills. The programme was designed to help some of our more stable patients gain their independence through what we called the trinity approach – regular counselling, group therapy sessions, and home visits. For some – for most – of the patients, SILC worked quite well. But for Billy, well, there were setbacks.’

‘What kind of setbacks?’ Striker asked.

‘Medication-related, mostly. Which sounds simple enough. But the medication was the only thing controlling his delusions. The group therapy sessions . . . these were aimed at the depression.’

‘And where exactly is Billy now?’

Dr Ostermann splayed his hands. ‘That’s the problem. I can’t get a hold of him. He is supposed to call into the office daily, but I’m afraid to say he hasn’t done so for quite some time. Almost a week.’ The doctor shook his head sadly. ‘This . . . unreliability was one of the reasons why he was removed from the group.’

‘Removed from the group, but not from the entire programme?’ Striker clarified.

‘Of course not, this is a rehabilitative programme, not a punitive one.’

‘You said, one of the reasons?’ Felicia noted.

Dr Ostermann nodded slowly. ‘Well, yes, there were other reasons as well.’

Striker pressed the issue. ‘What were they, Doctor?’

‘Billy had certain . . . obsessions.’

‘With what?’

‘More like with who,’ Dr Ostermann replied. He looked away from them for a brief moment and his lips puckered. ‘Billy was obsessed with Mandy Gill.’

‘Jesus Christ,’ Striker said. ‘You’re only telling us this now?’

Dr Ostermann raised his hands in surrender. ‘It was never in a violent way,’ he insisted. ‘These were completely non-violent obsessions, I can assure you of that. Billy was never a . . . violent person.’

‘He was a soldier,’ Striker pointed out. ‘He is at least familiar with violence.’

Dr Ostermann tilted his head as he spoke. ‘Billy may have been a soldier, but he was a communications officer first,’ he explained.

‘Communications officer or not, he is still trained for violence,’ Striker replied.

‘Did he have obsessions with any of the other patients or staff?’ Felicia asked.

‘Well, yes. There was another, yes.’

Striker felt his blood pressure rising. ‘Names, Doctor. Names.’

‘She was another one of the patients. Her name is Sarah Rose.’

The surname meant nothing to Striker, but the first name made him pause. Sarah? Wasn’t that one of the names written down on the large piece of paper back at Larisa’s home? He looked at Felicia, and she nodded; she too had made the connection.

‘Sarah was the only one who really looked out for Billy,’ Dr Ostermann continued. ‘The only one who genuinely cared for him. I guess she was Billy’s only, well, friend. They became close. Too close. A romantic relationship, I believe – which was strictly against the rules of the therapy. I was forced to remove them from the group. It was for this very reason Sarah broke off their relationship.’

Striker couldn’t believe his ears.

‘Broke off their relationship?’ He swore out loud. This was more than a mental health nightmare, it was a possible drugfuelled domestic. He calmed his mind down and focused on the basics.

‘Were Sarah and Mandy close?’ he asked.

The doctor seemed perplexed by the question. ‘Yes, I believe they were. As close as anyone could get to Sarah – she was quite introverted, you know. Almost a recluse. It was all I could do, at times, to have her attend the counselling sessions. One time, I even had to get my receptionist to—’

‘Hold on a second,’ Striker said. ‘Sarah Rose isn’t one of the in-house patients?’

‘Oh dear lord, no. Sarah’s depression is quite treatable.’

‘So she’s not actually here? She’s out there on her own?’

‘Yes, of course.’

‘Give me her telephone number.’

‘Sarah does not have a telephone, but I do have her address.’

‘Then give me that, and a photograph of the woman if you have one.’

From his desk, Dr Ostermann pulled out a file and removed a photocopy of a picture of the woman. He also pulled out an old-fashioned Rolodex, found the address, then wrote it down on a yellow Post-it note. ‘This is the most current information we have on Sarah.’

Striker took the photocopy of the woman’s picture as well as the Post-it note. ‘We can finish this discussion later,’ he said. ‘Right now, we have to check on this woman’s welfare. You had better hope, Doctor, that she’s okay.’

Dr Ostermann’s face took on a tight expression, but he said nothing back.

Striker turned and gave Felicia a nod, and the two left the office and made their way down the long dark corridors of the Riverglen Mental Health Facility. They returned to their car, got inside, and headed towards Vancouver. Destination: the Oppenheimer area. More specifically, the violent slums of Princess Avenue.

It was time to see Sarah Rose.