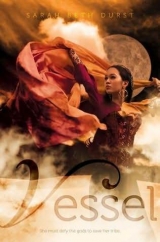

Текст книги "Vessel"

Автор книги: Sarah Beth Durst

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 12 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

Chapter Nineteen

The Emperor

The emperor pored over a stack of judgments. He couldn’t second-guess his judges, not without hearing the testimony for himself, but he needed them to know that he could overrule them if he chose. It was the best he could do at this distance from the palace.

Trust your people, his father had often said. An emperor isn’t one person; an emperor is all people, the embodiment of the empire. Rule with them, not over them.

He did trust them, at least most of them, on occasion and with supervision.

He added the flourish of his signature to a parchment, and then he massaged the back of his neck with one hand. Later, once they were within the desert, he wouldn’t have the leisure to attend to matters from the capital. He’d have to trust his people—just like they were trusting him now.

Suppressing a sigh, he picked up the next judgment, yet another petty land squabble. The number of cases had drastically increased due to the drought. Everyone was scrambling to hold as much land as possible, as if that would grant them security while their empire’s future shriveled around them.

“Your Imperial Majesty?”

The emperor raised his head. A soldier saluted him. He hadn’t knocked, a military habit that the emperor hadn’t tried to break. If a matter were important enough to bring to his attention, then it was important enough to skip the pleasantries.

“Our perimeter guards have apprehended a desert person,” the soldier said.

The emperor set down the judgments and straightened, aware he resembled a dog who had spotted a hare. The army often caught stray desert men near the border, but they rarely brought the matter to his attention. “And?”

“She demands an audience with you.”

“A bold demand,” the emperor commented.

“She was armed with only this.” The soldier laid a knife on the emperor’s desk. “A family heirloom, she claimed, and her gift to you.”

The emperor examined it. The blade was as clear as glass but felt harder than steel. He tested it on his desk, and it scored the wood as if the desk were sea foam, not the heart of an oak. He was certain that the blade was made from the scale of one of the glass sky serpents. His pulse raced, but he kept his voice as calm as a still lake. “Beautiful.” His scout had said that the serpent’s scales had cut like swords. The existence of this knife proved that the desert people had ways to defeat the sky serpents—yet another reason he needed them as part of his empire.

“She came to us in formal dress, unlike the other nomads we’ve encountered. She claims to be something called a ‘vessel,’ presumably a position of authority within her clan.”

A vessel, here. “Well. That is unusual.” He doubted that the soldier knew how much of an understatement that was. According to the magician, vessels never left their clans. Ever. They were treated like jewels—or prisoners. For a vessel to be here without her clan . . . Such a thing should be unheard of. “You were correct to come to me. I will see her.”

The soldier bowed. “Yes, sir.”

The emperor returned to reviewing the judgments, but he could not focus his attention on them. According to the magician, from the moment a vessel was “chosen,” he or she lost all control over his or her own life. Vessels were not allowed their own thoughts, their own choices, or their own futures. They sacrificed their lives to their clans long before their true sacrifice. He’d always been curious to meet one, and now he was flat-out intrigued. At the least, this should provide a welcome distraction while the army finished acquiring supplies.

Five soldiers marched into his tent. All of them halted, saluted, and then rotated to reveal a young woman. She was beautiful, as vessels were purported to be, with skin that looked like burnt cinnamon and features as perfect as a sculpture. Coiled in elaborate braids, her black hair shimmered in the light of the candles. Her dress flaunted every color in the sunset. Her hands had been tied in front of her, but she held her delicate chin high and her shoulders back as if she hadn’t even noticed the ropes. She met his gaze evenly with black eyes that were as clear and piercing as a sword. He’d imagined a subservient sacrifice. Instead she was a desert princess.

“Untie her,” the emperor ordered, his eyes not leaving hers. “Asking to speak with me is not a crime.”

The soldiers obeyed.

She held still while they cut the ropes, and her eyes stayed on the emperor’s. His soldiers removed the ropes and retreated, though not far. He approved of their caution. Even assassins could dress well. In fact, some of the finest assassins he knew were lovely.

“You have your audience,” the emperor said.

She raised her arms, and the sleeves fell back to reveal swirled tattoos on her arms. “I am Liyana, the vessel of Bayla of the Goat Clan, and I have come to tell you a story.”

Only a lifetime of habit kept the surprise from registering on his face. Keeping his expression carefully neutral, he gestured for her to proceed.

“Once, there was only sea. The moon loved the sea, for the moon was vain and her reflection was like a beautiful jewel on the water, but the sun wearied of the endless waves. All day he looked down on the same blue. So one day he burned hotter and hotter, and he dried the ocean. That night, the moon was horrified to see mountains and plains instead of her beloved sea. So she flooded the land. The next day the sun scorched the world again, and the next night the moon summoned the tides and covered it with water. This continued until at last there was only one creature left alive. It was a turtle, and she called to the sun and moon and begged for mercy—”

“You crossed a desert to speak to me about a turtle?” Most of his people considered stories fit only for children at bedtime. Certainly they’d never brave a desert crossing to tell their emperor a story. He had to fight to keep the excitement out of his voice and off his face.

“I speak of the turtle who was our mother,” Liyana said.

“I have heard many creation myths from the regions of my empire,” the emperor said, and he was pleased that his voice conveyed only mild interest. He was aware that his soldiers were listening. They knew it was a story that had led their emperor here—a story of magic that could save his people. But this woman couldn’t know that. “Fetch us water and dates,” the emperor ordered a soldier. The soldier bowed and exited.

The vessel continued. “She proposed a bargain: The moon could have an ocean if the sun could have an island. But when the sun created the island, he shone with such intensity that he scorched the center of it. In this barren desert, the turtle laid her egg. It hatched, and the desert people were born.”

“I had not heard this tale,” the emperor said. He continued to control his voice, as if this were only of passing amusement to him. In truth, he collected stories like past emperors collected rare jewels or exotic animals. This was the best way she could have chosen to capture his attention, but he wouldn’t let her know that. Accepting a golden dish of dates, he held it out to Liyana. She didn’t touch it. He ate one, and then poured water into two gold chalices. “You have a point in telling me, I presume?”

“The desert people exist to ensure that the moon remembers her promise to never flood again. If you threaten us, you threaten the whole of the world. You don’t want to do that. You want to leave and return to your green fields and blue lakes. Leave us to our sand. There’s nothing for you to gain here and much for you to lose.”

Chapter Twenty

Liyana presented the same smooth face that she’d shown her clan on the day of her summoning ceremony, and she hoped the emperor couldn’t hear the way her heart galloped inside her chest.

“You’d like us to leave because of a turtle’s bargain with celestial bodies.” The emperor sounded amused. He was younger than she’d expected, at most only a few years older than she was, but he had a presence that filled the tent. He held himself with a power and stillness that reminded her of carved stone.

“I ask you to leave because we belong to the desert, not to your green lands,” Liyana said. “We have no wish to join your empire.”

The emperor plucked another date from the tray and held it up as if contemplating its color in the candlelight. He let the silence stretch. Liyana kept herself still and silent as well. She knew this was a tactic—Mother wielded silence as a weapon too. Finally he asked, “How do you know that is why we are here?”

She chose a date from the platter to show she was not afraid. “You have an army camped at our border,” she said. “I assume they are not here simply to enjoy the heat.”

His mouth twitched.

She wondered if she had almost made him smile. “Of course I would be delighted if there were another explanation.” Feigning casualness, she bit into the date.

“It is my hope that your clans will join my empire without bloodshed.”

The sugar tasted sour in her mouth. She swallowed, forcing it down, as she tried not to imagine this vast army overwhelming her clan. “When the people of the turtle were born, many of them died in the harsh desert—these were the first deaths in this new world. Unfortunately, there was no place for the dead souls to go, so they wandered through the sky. This annoyed the stars, who loved their quiet and solitude. And so, one of the stars sacrificed himself and fell. He hit the desert with such force that he ripped a hole in the world. Flocking to this hole, the souls left our world—and discovered, or some say created, the Dreaming.”

“You may leave us,” the emperor said to the guards.

One of the soldiers looked as if he wished to object.

“If she assassinates me, you have full leave to declare war on the desert clans and exterminate every man, woman, and child you find.”

Liyana felt as if water, cold from a deep well, had been poured into her veins.

The soldiers bowed and filed out of the tent.

“Continue,” he said.

She clasped her hands together to hide their shaking. “The souls were happy in the Dreaming, but when they looked back at their desert home, they saw suffering. So they created the gods out of the magic of the Dreaming, and they sent the gods’ souls to walk among their people and help them live in their waterless world. Because of this, because of our deities, we of the desert are strong and free. And so we will remain.”

He fingered the sky serpent knife on his desk. She ached to take it back, take back her link with her family. “Tell me why you are truly here,” the emperor said.

She thought of Bayla and the Goat Clan, of Pia and Fennik and their deities and clans . . . and especially of Korbyn. “The empire has never shown an interest in our desert before. Tell me why you are here.”

His eyes widened, the first crack in his perfect, sculpted face. He placed the knife down, folded his hands, and leaned back as if to contemplate her from a distance. “You do realize that you are addressing the emperor of the Crescent Empire.”

“And you are addressing a free woman of the desert. You are not my emperor. Therefore I am your equal.” She felt like a rabbit blustering before a wolf. Everything about this man, or boy, radiated power. He sat at a wooden desk, a luxury that Liyana had never seen. It looked as if it weighed as much as a horse. Behind him were wooden shelves graced by glass sculptures. Each sculpture was a masterwork of perfect details: a fox with fur tufts on his ears, a falcon with outstretched wings, a cat poised midhunt. . . . Each one was more beautiful than the next. Only an emperor could have such impractical extravagance around him. She waited for his response, expecting to be savaged like a rabbit by a wolf.

“Very well then,” he said. “I should consider you a visiting dignitary?”

Liyana’s knees felt weak with relief, but she locked them and held herself straight and strong. “Use whatever terminology you wish.”

“Hostile visiting dignitary?”

“Cautious visiting dignitary,” Liyana said. “I am not here as an enemy, unless that is what you are.” She took a deep breath and asked, “Are you?”

To her shock, the emperor smiled. It transformed him from a stone sculpture into a flesh-and-blood human being. She was stunned for a moment by how handsome he was, the perfect beauty of his face. “You are refreshingly blunt,” he said.

“My mother would agree with you on that.”

“I do not wish to be your enemy or the enemy of your people. Indeed the empire has much to offer your people. And I believe you have much to offer us.” He twirled Jidali’s sky serpent knife between his fingers. She watched the glass-like blade catch the candlelight. “Mulaf, as always, your timing is impeccable.”

Liyana turned to see a man with a thick beard and sunken eyes enter the tent accompanied by a trio of guards. The man wore the robes of a desert clansman, though she didn’t recognize the patterns embroidered on the blue silk panels. He bowed to the emperor while his eyes swept over Liyana. She took a step backward. His gaze felt like a lick of fire.

“She is Liyana, the vessel of Bayla of the Goat Clan,” the emperor said. “This is Mulaf, chief magician to the Crescent Empire. Mulaf, this woman is a visiting dignitary and my personal guest. Show her to a tent and then return to me. We have much to discuss.”

In contrast to the expressionless emperor, Mulaf was awash with emotions. His face twisted and stretched. His eyes narrowed then widened. At last he said, “I would be honored to escort her, Your Imperial Majesty. Please, accompany me.”

The trio of guards closed around her, and she was swept out of the tent flap without any chance to protest. Outside, other soldiers sealed into a line, effectively blocking her return. She looked back at the golden tent. She hadn’t asked about Pia and Raan, or Korbyn and Fennik, for fear that would endanger them further. Had that been a mistake? She ran through her mind what she’d said. Had she chosen the right words? Had she done any good at all? He’d seemed . . . interested in what she had to say. He’d listened to her stories. She wasn’t certain a clan chief would have done as much, and he was the emperor of a vast land. He had even let her speak with him alone, though she didn’t doubt that the guards had lurked mere inches beyond the tarp. But if she had expected a miracle . . . He wasn’t about to withdraw his army, and she had not found the stolen deities.

Now what? She hadn’t planned beyond speaking with the emperor.

With the guards, Mulaf escorted Liyana through the encampment. She noticed that all the tents were identical—green, triangular, and plain. There were no names or stories woven into the tarps. She saw no smoke from cooking fires within. All the fires were outside and tended by soldiers. She saw no children.

Liyana had expected the emperor’s people to look different from the sun-worn desert people, but she hadn’t expected them to be so different from one another. One had a narrow, pale face with a nose as pointed as an arrow. Another was dark skinned and wore a full beard. A third sported tattooed dots over his cheeks. All of them, though, bore the serious look of men and women with weapons. All of them, also, looked too thin. She saw pinched cheeks, bony shoulder blades, and uniforms that hung loosely on gaunt bodies. Everyone had a task, whether it was repairing a boot or fixing a meal or patrolling between the tents, but everyone paused to watch her pass—or perhaps they watched Mulaf.

She studied him as he shepherded her through the encampment. His beard was riddled with white, but he moved like a jackrabbit with a startled leap to his step. His eyes darted fast in all directions. She noticed he didn’t greet anyone, and no one greeted him.

“I didn’t know the empire had magicians,” Liyana said.

His smile was tight-lipped. “I have been blessed with good fortune.”

He led her to a nondescript tent, and the guards positioned themselves on either side of the tent flap. Mulaf ushered her inside. Inside, the furnishings were minimal. A few unhandsome blankets had been tossed around the floor as rugs. A cot with a thin pillow was set up on one side. A washbasin stood on a stand in a corner next to a pot. It all smelled faintly of urine. She wondered if she was a prisoner.

He dropped to sit cross-legged on one of the blankets. “Come. Sit. I apologize for not offering you tea.” He smiled broadly at her in what she was certain he meant to be a reassuring manner, and he patted the blanket next to him.

Liyana lowered herself onto a blanket several yards away from Mulaf. She wished she had her sky serpent knife.

“Tell me, my dear child . . . Liyana, is it? How did you escape your clan?” he asked. His eyes were as bright as a desert rat’s, and he leaned forward eagerly.

She stuck to the truth, or at least part of it. “My goddess didn’t come, so my clan exiled me.”

He clucked his tongue. “What a shock that must have been.”

“Yes, it was.”

He bounced to his feet and paced in a circle around her. “Bayla of the Goat Clan did not come. What a pity. What a tragedy.” Without warning he dropped to a squat in front of her. There was something about him that made her think of a bird fluttering with a broken wing. Instinctively she pulled her knees toward her chest and shrank away. “You are a lucky girl, you know.” He reached out and stroked her cheek with a fingernail. “You have an opportunity that no other vessel has ever had. You can make your own life in the empire. You can change your fate!”

She wanted to bolt out of the tent. The tarp walls felt as if they were pressing inward. She inched backward, away from Mulaf. “When did you escape your clan?”

He laughed like a hyena. “Years ago, my dear. Would you believe that I am over one hundred years old? I am from the Cat Clan. I was once their magician.” Popping to his feet, he paced again.

She’d heard of the Cat Clan. One hundred years ago, the clan had become extinct. An abnormal number of disasters had befallen them, one after another. They had been hunted by sand wolves, attacked by sky serpents, caught in quicksand. Stories about the Cat Clan were whispered late at night when the camp’s fire burned high enough to stroke the stars. If he were truly from the Cat Clan, then it was no wonder he saw the empire as a sanctuary. “It must be difficult for you to live with people who aren’t the turtle’s children.” She tried for a note of polite sympathy while she calculated the distance to the tent flap—she could reach it in three strides.

He snorted. “Turtle. Another lie told by the parasites. Oh yes, the desert people are the special chosen ones. Chosen to be prey for the parasites!” He squatted again in front of her. His face was too close. “You don’t believe me. I can see it in your eyes. But you will, once you have tasted the freedom that the empire has to offer.”

She shrank back. “When will I be able to speak with the emperor again?”

“The emperor will grant you sanctuary, I can assure you,” Mulaf said. “In time you will understand that you are safe here.”

“Am I?” She breathed the scent of his breath, sour as rancid goat’s milk.

“Oh yes, Bayla’s vessel. You never need to fear your goddess again.”

She forced herself to sit still while everything inside her shrieked. He knows! She wanted to leap at him and force the truth out of him. Tell me what you’ve done to her! But in the heart of the empire’s army, she didn’t dare move.

The magician rose to his feet. “Welcome to the Crescent Empire, Liyana.”

Chapter Twenty-One

Alone, Liyana huddled in the center of the tent. Sweet Bayla, what have I done? She’d walked willingly into a cage, as stupidly as a goat to slaughter. She wrapped her arms around her knees as waves of terror crashed over her.

She didn’t know how much time had passed while she had been trapped inside her own fear, but minutes or hours later, a soldier shoved the tent flap open and strode inside. He wore the white uniform with a red scarf, but his shoulders were decorated with swirls of gold. His face had the same pinched look as the others she’d seen, but he was older, so the flesh hung on his cheeks like loose cloth. Based on his age and the gold on his shoulder, she guessed he was an officer, perhaps even a high-ranking one. He bowed. “The emperor requests that you join him for dinner.”

She tried not to look as surprised as she felt. Standing, she smoothed her skirt. “I’d be delighted.” He led the way out of the tent, and she followed.

She couldn’t imagine why the emperor had requested her. Had he connected her with Pia and Raan? Or Korbyn and Fennik? If so, why honor her with dinner? Reaching the emperor’s golden tent, the officer raised the flap. As the guards watched her, she was shepherded inside and then, again to her shock, was left alone with the emperor.

Surrounded by embroidered pillows, the emperor sat on a gilded chair. “Please, join me,” he said. He indicated a second chair across a table.

She sat, feeling like a bird on an awkward perch. She was far more used to pillows or, lately, sand. The table between them was inlaid with a mosaic of smooth stones. It depicted a river running through green farmland. It was an utterly impractical item for a tent. “You are usually a stationary people?” she asked. She gestured at the table, as well as the massive wood desk and the shelves with the glass sculptures.

“Indeed,” the emperor said. “Our land feeds us where we live—or did until the Great Drought began.”

“I hadn’t known the drought touched the empire too. I . . . am sorry to hear it.” Liyana wondered if Raan had seen the gaunt faces of the soldiers and realized what they meant. She’d wanted so badly for the empire to be the answer.

“My empire and your desert . . . We are all one land. The Great Drought affects us all.” He leaned forward. “But together, we can survive it. We are here to offer . . . cooperation. The desert people cannot survive alone.”

“We are not alone,” Liyana said. “With our deities, we will survive it.” Raan had been so hopeful when they had neared the border. The truth must have crushed her.

“And you would have given your body to your deity to ensure that?”

She wondered what the magician had told him and whether the emperor believed she had escaped and wanted sanctuary. She chose a cautious answer. “I was chosen to do so.”

“A shame,” he said.

In that one word, she heard the condemnation of her people’s choices, their stories, and their way of life. It was worse than Raan’s condemnation. This stranger with his silk robes and jeweled fingers dared pass judgment on her people, when her people had survived the harsh desert for a thousand years. “My clan deserves to live, and I was honored to grant them that life.”

“The empire can grant them life if they join us.”

“How can it if it can’t feed its own people?” she countered.

Abruptly he rose. She thought for a moment that she had gone too far and angered him. She waited for him to summon his guards, but instead he paced the breadth of the tent. At last he halted directly before her. Light from a lantern flickered over his face. “I have dreamed of an oval lake in a lush, green valley. Granite cliffs surround it, and it laps at a pebble shore. This lake holds the answers.”

Liyana felt as though her ribs had pierced her lungs. He’d described her lake, the one she pictured when she worked magic, in perfect detail.

Before she could formulate a response, servants entered the tent carrying an array of trays. One carried a silver platter of fluffed breads. Another held a bowl of fruit on his head. A third brought a tray of steaming spiced meats. The servants placed their bowls and platters on the mosaic table, bowed, and retreated.

The emperor sank into his chair. She thought she saw tiredness around his eyes. He focused on the feast before them, but she suspected that he wasn’t seeing it. She wondered what thoughts were churning in his mind and how the emperor of the Crescent Empire could have dreamed of a lake she’d imagined.

“Tell me about the Dreaming,” the emperor said, eyes on her. All trace of exhaustion vanished. He seemed intent on her response.

“Once, the raven and the horse had a race. . . .” She told him the story of Korbyn and Sendar, and how Korbyn had bent the desert in the Dreaming in order to win. “The Dreaming is a place of pure magic.”

He nodded as if the story had pleased him. “And the lake is made of that same magic, spilling into our world through the rift made by the star. Your magicians and your deities draw their power from that lake.”

“I . . . I have heard that magicians imagine a lake to symbolize the source of magic.” She didn’t want to admit that she had done so herself in defiance of tradition. “But I don’t believe that it exists.” She had simply imagined it. Korbyn hadn’t even described it. Certainly not the granite cliffs or the pebble shore . . . “Stories are sometimes just stories.”

“Nothing is ‘just’ a story,” the emperor said. He reminded her of an ember, quietly burning but with the potential inside to explode into a wildfire that would chase across the grasslands and destroy all life. “The lake is real.”

“I don’t believe—”

“There is a man, one of my soldiers, who has seen it. But the lake is guarded by glass sky serpents.” He pulled Jidali’s knife out of a pocket in his silk robes. “Your people know about the sky serpents. Tell me what you know. Tell me how to defeat them!”

“I know of no one who has defeated them,” Liyana said. “And the sky serpents guard the mountains, not a lake.”

“Tell me of the sky serpents and the mountains.”

“Once, the sky serpents preyed on the people of the desert. Arrows could not pierce their scales. Swords could not slice their skin. The serpents attacked men, women, and children, and they left death in their wake. Seeing the destruction and fearing for their clans, the gods bargained with the sky serpents. The sky serpents would not harm any of the desert people, and in return no human would ever set foot in the mountains—”

He leaned forward, his hands clasped in front of him, his face alive with excitement. “You have never wondered what lies within those mountains? If there are peaks, there must be valleys! And if there are valleys . . . one of them could hold the lake.”

“We call them the forbidden mountains for a reason. Break the promise with the sky serpents, and they’ll attack. That knife . . . My ancestor didn’t defeat a sky serpent. No one ever has!”

“No one has ever directed an army such as this to the task.” The emperor spread his arms to indicate the whole encampment.

“You can’t! You’ll be killed! And the sky serpents will turn on all of us!” There would be no defense. Her people would be slaughtered.

“We have no choice but to try. My people are dying. We need the magic of the lake so that we can survive.” He clasped her hands. She’d expected his hands to feel as cool as gold, but his hands were warm as they enveloped hers. “I cannot allow my people to die. You of all people should understand that, vessel of the Goat Clan.”

She stared at their hands, entwined. The crazy thing was that she did understand. She even admired him for it—after all, his plan to march into the desert mountains to find magic was not so different from her plan to march into an army encampment to find her goddess. Both were mad, and both were necessary. “There must be another way,” she said. “Pray to your gods! Ask them to join you as ours do.”

Releasing her hands, he withdrew. “Let me tell you a story of my people. Once, there were only gods on our world, and each of them was an artist. The sculptor shaped the dirt to create the mountains, valleys, and plains. The weaver wove roots under the ground and grew the plants, trees, and flowers. The singer created the birds. The dancer created the animals. And the painter filled the world with light and shadow. When the gods finished, they looked at the world and said to one another, ‘But there is no one to enjoy this beauty.’ And so they worked together—sculptor, weaver, singer, dancer, painter—to create people to live in their world. When they finished, they were pleased. They said to one another, ‘Let us find a new world to fill,’ and so they departed, leaving us this world to enjoy.”

He fell silent as the servants filed into the tent and filled two chalices with water that smelled like fruit. The emperor waved them away from the untouched food. Bowing, they exited.

Liyana tried to imagine such horrible emptiness. Facing the world knowing that you were alone . . . “Your gods left you?”

“They left us the gift of a world,” he corrected.

“But that’s not enough,” Liyana said. “You can’t fix a drought alone.”

“With the magic of the lake, I believe we can.”

Liyana could only stare at the emperor, this handsome boy-king filled with such light in the glory of his impossible dream. “People will die,” she said flatly. “Yours. Mine. The clans will never allow you to violate the peace of the forbidden mountains.”

He took her hands again. “That is why I need your help.”

“Me?” Her voice squeaked.

“Once we cross the desert border, we will begin to encounter the clans,” the emperor said. “Someone must explain our cause to them—prevent misunderstandings and encourage cooperation. You have met Mulaf. He is ill suited to such a task. But you, a vessel, one of the desert’s own precious jewels . . .”

“I . . .” She pulled her hands away from his.

“Think on it tonight,” the emperor said. “I will not force a free woman of the desert. But through your words and actions, you could save many lives.” He handed her a chalice of fruit-water. “Drink. Eat. You may answer me in the morning. We will speak of it no more now.”

She took the chalice.

* * *

Liyana’s dreams that night were filled with armies and sky serpents and an emperor with shining eyes who toasted her health with a gold chalice. She woke before dawn and discovered that her water pitcher had been refilled, and that a sapphire-blue robe, the same style as the emperor’s, had been left for her. She hesitated—her ceremonial dress was creased, but she did not want to lose it. On the other hand, she did not want to offend. Hoping her clan would forgive her, she dressed in the robe. The fine fabric felt like a whisper on her skin, but she felt as if she wore a nightshirt.