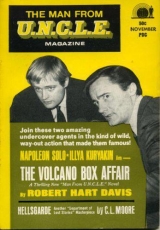

Текст книги "[Magazine 1967-11] - The Volacano Box Affair"

Автор книги: Robert Hart Davis

Жанры:

Боевики

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 2 (всего у книги 5 страниц)

In those seconds was disclosed the awesome spectacle of a volcano being born. The crags of the island were no more, and in their place seethed a fiery mass of molten lava, from the center of which radiated great waves of white-capped water. Then the lava spilled out over the rim of its crater and sent gigantic plumes and geysers of steam thousands of feet into the air.

The rumble of material pouring from the world's bowels, the searing hiss of ocean converted into steam, the orange river of magma flowing into the sea, and the stench of sulfur resembled nothing less than a nightmare out of Dante.

Edward Dacian, who had thought he knew what to expect, sat stupefied, his mouth open. The rest of the team stared in almost humble silence. Only Kae Soong appeared fully calm. He gazed, eyes wide with pleasure and lips drawn in a smile of satisfaction, at the product of the most potent weapon ever created.

"It occurred at four thirty-eight, not four forty-one," he finally remarked to his captive as the helicopters turned away from the first man-made volcano ever created.

"Nobody's perfect," Dacian explained.

ACT III

FOR SALE—DEATH

ALTHOUGH THREE people were waiting ahead of him, the bony man was admitted as soon as he announced himself to the secretary.

"This way, Mr. Rawlings. Mr. Greyling has been expecting you." The petite girl, her red jumper shifting provocatively as she led him down a corridor, had been most eager to accommodate him. She thrust open the door to Mr. Greyling's office and bade him pass before her.

She led the bony guest into an inner office and introduced him to its occupant, a squat, florid man with crew-cut grey hair and a too-ingratiating, almost fatuous grin. They shook hands and both Greyling and his secretary tripped over each other to help their guest into his seat.

"You'll let me offer you some thing, won't you? Buy you breakfast, perhaps?" Greyling said to his guest.

"I don't think so," Rawlings said. "Suppose we get right down to business."

"Fine, fine. Couldn't ask for anything more. That's the way I like to do things. Roll up your sleeves and plunge right in."

Greyling spread his lips in an almost leering grin. Then his eyes focused on the thin grey scar on the left side of Rawlings' brow. It was an interesting wound, but Greyling decided it was best to say nothing about it. Greyling had a weird-shaped war wound on his belly and didn't mind talking about it, but some folks are funny about these things. The deal was too important to risk offending this character.

"Well," said Greyling, "as I understand it, you're interested in the Sperber property. If you don't mind my saying so, you're a very shrewd man indeed, Mr. Rawlings. Fifteen years ago, that bunch of oil wells promised to be the biggest producer in Oklahoma, maybe even in the southwest. But the men who tapped the well were after the fast buck. Know what I mean?

"They just wanted to skim the surface oil, raise it by means of the gas pocket down that hole, and when the gas fizzled out they didn't care a hoot for building a rig to pump the rest of the stuff out. So as far as anyone knows, there's a mighty big pool of black gold sitting under the Sperber property waiting for the right man to invest a little dough and bring it up."

He looked into Rawlings faded blue eyes for a sign of greed—the dilated pupil, the glazed stare he had seen so often as he began to weave one of his preposterous stories to hook the real estate sucker.

But no such change came over Rawlings' countenance. It remained calm and almost dispassionate. The bony man had simply nodded politely as Greyling did his spiel, and then looked at him blankly when the speech was over.

Greyling began to wonder. The guy didn't really seem to care what story he told him; he was, as he'd announced on the phone, desirous of buying the Sperber property and didn't need to be sold on it. Well then, Greyling said to himself, don't try to sell the guy on it, otherwise you may sell yourself right out of a sale.

"Uh, tell me, Mr. Rawlings," the broker said, hoping to find out what kind of backing the man had, "what's the name of your firm?"

"Land Development Enterprises," Rawlings said flatly.

"I see. Can't say as how I'm familiar with that one," be said. Obviously a dummy corporation, Greyling concluded, and after putting a few more leading questions to his guest abandoned the inquiries.

It was clear that whoever wanted this land didn't want his identity revealed, which meant Greyling would be unable to estimate what the buyer had in mind as far as price was concerned. So he would have to resort to the time-honored system of offer and acceptance, which in turn meant getting the buyer to name his price. "Just what terms did your firm have in mind?" he asked.

"You said on the phone," countered the visitor, "that you could name a fair price."

Greyling frowned. He hated to start the bargaining, but obviously the men behind Rawlings were good bargainers, and with a cow-pasture like the Sperber property anything over five digits was a killing. So he launched a ten-minute tirade on the beauties of the land, the untapped wealth below its surface, the relative prices of land in the area, the booming economy, his personal troubles and, in case Rawlings wanted the land for something other than its oil wells, its potential value both as farm and factory property.

Towards the end of his speech his visitor began looking around the room and shifting in his seat. Greyling had a good sense of audience and realized he was putting off his guest, so he hastened to his conclusion and said, "So I don't think I'm being at all unreasonable in suggesting thirty-five thousand for the land. I have so much faith in those wells that I'm tempted to request a royalty on the oil you raise, but if you pay the full amount now, in cash, I'll drop that request."

Greyling settled back in his chair and strained the muscles of his face against the temptation to look eager. His eyes scrutinized the face of his customer for that pained reaction that inevitably appeared when a ridiculous price was named.

However no expression except thoughtfulness crossed Rawlings' demeanor, and, after only a few moments, he said, "That will be acceptable."

Greyling suppressed a gasp. Barely, controlling the tremble in his voice, he buzzed his secretary and said "Please come in with a deed blank, and your pad and pencil. And be prompt. Mr. Rawlings is in a hurry."

TWO

IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA, in Pennsylvania, in Florida and in about six other key locations in the United States, similar negotiations were being carried on. In each case the buyer represented a dummy company interested in buying an abandoned oil property. And in each case the broker or principal named a price far too high, expecting a counter-proposition. And in each case the terms were accepted calmly, to the astonishment of the seller.

And after the papers were drawn up, the seller inevitably wondered, as his pen poised to sign his property over to the purchaser, if he had perhaps not sold it too cheaply.

But the phenomenon was not restricted to the United States. Similar deals were being consummated in such widely divergent places as Venezuela, Arabia, Iran, France, Turkey, and even in Communist countries, where land was not held privately, arrangements were made for an unknown syndicate to occupy an abandoned oil site. Within a period of weeks a network of such sites or, if the nation had no oil facilities, old mineshafts, had been established around the globe.

After each site was secure the agent would send a coded cable to Singapore, where a stocky but rather tall Oriental read it with satisfaction and pushed another pin into his atlas.

THREE

THE LABORATORIES of Gulf Coast Power and Light were set off from the immense complex of grids and high voltage equipment that sprawled over twenty acres of southwestern Texas land. The large white adobe building seemed to shrink under the intimidating whine of the machinery on the other side of the decorative pond that set it off.

Illya Kuryakin crossed the little foot bridge over that pond. Lilies floated on its surface and goldfish darted from under a rock. He paused to admire this little tribute to peacefulness amid the shrieks and hums of high-powered hardware.

Beyond the pond, about thirty yards from the laboratory, a laminated steel fence had been erected with signs suggesting that a curious person would be treated with considerable displeasure.

But the fence did not conceal entirely the scaffolding inside it, which rose almost as high as that of an oil well.

Illya continued across the bridge and passed through the doors of the laboratory, where he was greeted by a red-headed receptionist whose eyes reflected their appreciation for Illya's blond, steel-eyed good looks.

She announced him to the lady who was expecting him, and with disappointment showed him to an inner office and turned him over to Frieda Winter.

Her official title, according to the lettering on her door, was assistant director of experimental projects, and Illya, thinking in stereotypes, had expected a stout woman with mousy hair, horn-rimmed glasses and a white smock that would display about as much figure as a pup tent.

If he was disappointed, it certainly didn't show in the warm glow that spread over his cheeks as his eyes took her in. She was, for a laboratory worker and administrator, quite a dish. Her hair was dark auburn, almost black with red highlights, and her eyes hazel and round and intense. She wore no smock at all, but a red skirt with matching sweater that revealed a splendid figure.

During the course of conversation Illya Kuryakin managed to sneak a look at her ankles, hoping to find some disfigurement that would release him from having to be interested in Frieda Winter the woman, and enable him to pay the strictest attention to Frieda Winter the scientist. But her ankles were as well-turned as any item of fine furniture.

Evidently she was thinking much the same thing about him, for she said, "I somehow expected a Dick Tracy hat and the rest of the G-Man bit."

Illya smiled boyishly. "No, the investigative offices have become very cool these days. I mean, we try to be cool. It makes our enemies think we're not scared to death. It also," he added, "makes women think we're not terribly interested in them."

"I suppose that's a good thing, professionally speaking."

"Professionally speaking," Illya said. They exchanged glances, then Illya dropped his eyes, sighed, and said, "Suppose we speak professionally then."

"Yes." She walked to her desk and sat down. "How much do you know about Dr. Dacian and his work?"

"Quite a lot, but suppose you tell me everything, from the way he was hired to the events of the last day you saw him. Then I'd like you to show me the apparatus and explain its operation to me as completely as you can. I have more technical knowledge than you think, but quite a lot less than I'd like to have, so speak to me like a colleague but don't be surprised when I ask some incredibly stupid questions."

She smiled. Then, after ordering coffee from the laboratory cafeteria, she began to tell Illya all about the engagement of Edward Dacian by Gulf Coast Power and Light.

It had been well known that Gulf Coast was experimenting with the idea of tapping the heat beneath the mantle of the earth to produce cheap electricity, and Dacian had read about the lab's work in a journal. Their experiments corresponded to some he had been performing at Colorado School of Mining, but the school simply couldn't put at his disposal the kind of financial backing he needed to explore his ideas to their logical conclusion. Thus he got in touch with Gulf Coast and was hired.

Within eight months he had constructed a laser of enormous power, operating on light transmitted through gas instead of crystal and using a system of "mirrors" which were made of opaque liquids contained in saucer-shaped crystal containers.

The liquids intensified the laser beam terrifically, but their formula was known only to Dr. Dacian, and they constituted the essence of his earth-piercing apparatus.

"Dr. Dacian," Frieda Winter explained, "learned that the beam works most effectively in already-existing shafts. The beam, in other words, is poor at starting a hole, but if it operates in a well the walls of the shaft contain the potency of the beam. The beam works faster the deeper the shaft. We ascertained that it took the beam twenty-four hours to dig through the first two thousand feet of surface, twelve hours to pierce the next two thousand, and so on almost in geometric proportions."

"In other words, it would take about forty-eight hours to penetrate the mantle in a land formation of average depth, but only about two if the beam were sent down a shaft the depth, say, of an average oil well."

The girl looked at him with admiration.

"It didn't take very long for you to calculate that," she said.

"In most things I think fast. Now tell me, was Dr. Dacian's progress publicized?"

"Only by word of mouth. We tried to prevent official publicity and tried to stop gossip, but unfortunately people aren't made that way, and I imagine somebody got loose-tongued over a drink. I assure you it wasn't I," she said quickly.

"You needn't be defensive," the U.N.C.L.E. agent assured her. "Now I'd like you to tell me, or check for me, whether during this time any suspicious individuals came to work for your company. It stands to reason that the persons most suspect are those who quit their jobs around the same time as Dacian disappeared."

Frieda Winter handed Illya Kuryakin a slim file. "You'll find in there the records of six people who joined the company, in capacities ranging from janitor to executive, and left in a period ranging from two weeks before to two weeks after Dr. Dacian's disappearance. Everyone else has been checked thoroughly or is under surveillance, but these six have not been located."

Illya removed six smaller envelopes from the file and opened each, removing neatly arranged dossiers on the individuals in question. They contained, among other things, a photograph of the person, used on identification badges or cards which all personnel were required to carry with them at all times.

Illya, one of whose duties was to brief himself regularly on the faces of his antagonists, glanced quickly at each picture, studying it and comparing it with a mental image in his brain's rogue's gallery.

On the fifth photo his eyes widened. The bony face, the angular Adam's apple, the unusual grey scar on the brow, tallied with a face Illya knew.

He studied the accompanying documents: Paul Rollins, alias Rawlings and a few other pseudonyms, had come to work for Gulf Coast as a groundskeeper. His employers had not bothered to check on background or references for such an inconsequential job, but after Dacian's disappearance an investigation had disclosed that Rollins had been involved in a number of criminal activities and had a prison record. He had also been arraigned on a kidnapping charge but his case had been dismissed for lack of evidence.

"This looks like our man," Illya said.

"Most likely it is," Frieda said. "The F.B.I. agrees and is already putting a search out for him. And incidentally—"

Illya anticipated her question. "I work for a different outfit," he explained, "and all I can tell you is that we're good guys, just like the F.B.I. But we aren't too chummy with those fellows, and besides, our records are often more complete than theirs."

"I see."

"I would like to transit this material to my superior officers so that they can run routine checks on the other five, but I would especially like to find out as much as possible about this Rollins. Perhaps during lunch—."

"As much as we know about him is in that envelope," Frieda said lugubriously. "But perhaps we can find another excuse for lunch."

"Would mutual hunger be acceptable?"

"You are a fast thinker!"

They went to the laboratory's cafeteria and took their seats at a table away from other diners. After the main course the U.N.C.L.E. agent excused himself and contacted Waverly, telling him as much as he'd learned and suggesting that all data on Paul Rollins be sifted and the man's current whereabouts be traced if possible. Then Illya returned to the cafeteria for dessert and coffee.

"I want to hear more about Dr. Dacian's experiments," he said. "Did he ever suggest when talking to you, for instance, that his beam might have a potential other than peaceful?"

"Yes, he did. Well, let me put it this way. He said to me once that he shuddered to think of what might happen if the instrument were used by someone who didn't know exactly what he was doing. Then he thought for a moment and said he shuddered even more to think that it might fall into the hands of a wicked person who did know exactly what he was doing."

"How well did you know Dr. Dacian?"

"We were good friends," Frieda said, her face registered no indication that anything more serious might have existed between them. "He was an enormously outgoing and expansive man. He wore his heart on his sleeve and I don't think there was a furtive or dishonest bone in his body. He was patriotic, and he had a strong revulsion to what he called wickedness. In short, Mr. Kuryakin, he was a peaceful man, and it would take overwhelming evidence to make me believe he defected or sold out."

"Calm down," Illya said. "I never suggested anything of the sort. I only want to know if he realized that the peaceful instrument he had created might also be converted into a weapon. And I suppose I want to know to what extent he could resist pressure to disclose his formulas to anyone he suspected of having 'wicked' intentions."

"I believe Edward Dacian would die before revealing them. He was that kind of man."

"Yes, but could he be forced to produce the rigs themselves?"

"I just don't know. I'm told that wicked people use some rather nasty techniques for coercing their fellow men."

Illya smiled. "That is about the mildest statement I have ever heard. You're very charming, Miss Winter."

The girl blushed, and an embarrassed pause ensued. Then she said "I imagine you're interested in a demonstration. Why don't we go behind the laboratory and look at Dr. Dacian's apparatus."

"Fine."

They pushed away from the table and proceeded out the building into a garden in the rear. The sun was strong and warm, and the air was fragrant with perfume from semi-tropical flowers.

Frieda Winter unlocked the door of the compound and they entered. She reached under an almost invisible bubble in the fence and switched off an electric eye guarding the perimeter of the rig. They then strolled up to the scaffolding, and Illya scrambled under the pipes and tubes to get a closer look at the machinery at the center. It was disappointingly simple, the vital mechanisms being sheathed in steel so that only a tubular lens extended from the box's belly. A shaft about a yard in diameter yawned beneath the tube.

A thick pipeline emerged from the ground near the rig, and nearby on a kind of dolly stood a complicated knot of ducts, valves, gauges and the like.

"Water is pumped into the shaft from that pipeline," Frieda explained. "Of course, if the shaft extended from a river bed or ocean floor, we would not need to pump in water at all. But since it would have been too expensive to do that for experimental purposes, we simply tapped the Gulf waters. Come here."

She beckoned to Kuryakin to stand near the mouth of the shaft. He approached it but by the time he was standing by her side the heat from the bowels of the earth was almost intolerable. They backed off.

"Once the shaft is dug by the beam, the water is passed into it under controlled means, and this apparatus here," she said pointing to the dolly, "is sealed over the shaft. It receives the steam and keeps it superheated until it can be converted into mechanical energy. Of course, if this were an electric plant, a number of shafts would be sent down, and they would be considerably wider than this one, you understand.

"And they would be harnessed directly to dynamos instead of linked up from a distance, as we've done here. Nevertheless, as crude as our apparatus is, we've produced electricity more abundantly and cheaply than any other source known to man. And all we do," she smiled, "is add water."

"But if you sent your beam too far—"

"We would have the first active volcano in the continental United States, to state the matter unimaginatively."

They gazed at the apparatus respectfully, then returned to the laboratory.

ACT IV

KEY TO HELL

THE TRUCK PULLED up to the prefabricated hut on the Sperber site, and the driver and two helpers got out of the cab. The driver knocked on the door of the hut and was greeted by a gaunt man with a funereal expression on his face and a strange grey scar running almost from temple to temple.

The driver thrust a set of papers under the bony man's nose, murmuring, "Scaffolding."

While Paul Rollins, alias Rawlings, was examining the bill of lading, the driver and his helpers ambled away and gazed with perplexity at the bleak property. Some scrubby trees grew here and there, and wild grass and sage covered the rocky soil to the edge of the property, which was bounded by a range of hills on the west and a river on the east and south.

Spaced out at intervals of an acre or so were the skeletons of oil rigs, rusty and useless.

The driver pushed his Stetson up on his brow and scratched his balding head.

'What do you think?" be whispered.

"I think they either know there's oil down there, or else they're all crazy as bedbugs," said one helper.

"If there's oil down there," said the other helper, "I'll drink a glass of it before breakfast every day for the rest of my life."

"Maybe they're not drilling for oil?" said the first.

"Of course not," said the driver, "they're drilling for high octane gasoline."

The three men laughed, and then one of the helpers said "Truthfully, now, what kind of rig can they construct with the scaffolding we brung 'em? There ain't enough there to construct any kind of oil rig I've ever seen, and I've seen 'em all."

"Maybe they're expecting another load of scaffolding, or getting it from some other outfit than us," the driver surmised.

"Maybe," his assistants agreed. "But if that's all they're using," the driver went on, "I don't reckon they'll get much deeper than fifty yards."

They chuckled again and ambled back to the hut, where the bony man gave them their signed copies of the papers. They unloaded the pipes, plates, and hardware and departed, smirking.

Rollins assembled his crew and they set about wrecking the pumping rig over the well furthest from the road. After it had been removed, the crew carried the scaffolding to the well and began erecting a low rig resembling a quarter-scale model of an oil-drilling tower. A square space was left in the middle over the oil shaft, a space exactly the dimensions of Edward Dacian's volcano box. When the job was done, Rollins had a. coded message cabled to Singapore.

And from several dozen other places throughout the world, similar cables issued.

TWO

EDWARD DACIAN raised his heavy eyelids and looked at the ceiling of his cell. It was white and sterile, and he silently gave thanks that although he was a prisoner he was not being held in a dank, cold dungeon. The place was white-plastered, air-conditioned, and, though austere, not uncomfortable.

The only trouble was that his captors were not feeding him. His bowels had been playing games with his system the last few days, alternating between severe diarrhea and severe constriction. And now there was nothing at all in his stomach and it didn't matter; he felt nothing.

They had not begun to torture him yet, but he knew it must follow soon. Because he was a coward he had allowed himself to be frightened into a limited agreement. He would construct his devices, one at a time, with the materials they provided for him. But he would not disclose the formula by which the devices were put together, nor the secret of the liquid mirrors by which the laser beam was intensified to literally earth-shattering proportions.

He had bluffed them into believing that he would give up his life before revealing those formulas, but in his heart he doubted whether he could withstand physical agony. And so, dawdling as best he could, he made his machines and was almost finished with the third. The first had created the volcano in one of the numerous Luciparan islands.

The second had all but wiped Tapwana, the rebellious island, off the map. And this one? It would undoubtedly be employed against a target considerably more ambitious than a petty island.

He knew he had little time left before they lost their patience with him. Yesterday they had taken him to a factory where he had seen three dozen of his machines being constructed. They had of course analyzed his other two and used them as bases for this large crop. Nevertheless his special formulas had eluded their analyses so far, and when they were through with the devices they would really begin pressing him to give away the essential secret so that the mirrors could be installed.

From what he could see of their progress on the basic device, he had only a few days left.

Then it would be torture.

He thought about the ancient tortures, racks and things like that, but he knew they had far more sophisticated ones than those nowadays. He had seen pictures of men whose brains had been so scrambled they were mere puppets. He could be one of them. The mere thought sent a ripple down his spine.

They were softening him up. Already the want of food and sleep was beginning to tell on him. He had begun to wonder what difference it made who had the formula or what was done with it. If the human race was hell-bent on destroying itself, it would be done whether they used his device or atomic bombs or fists and teeth.

But no, that train of thought was contrary to everything he had come to hold dear. There were still decent people in the world, and he could never obliterate the distinction in his mind between those decent ones and the wicked ones. Before he did his mind itself would be obliterated.

Dr. Edward Dacian gazed at the white ceiling, wondering just how much pain he could stand before they made him tell.

THREE

ALEXANDER WAVERLY studied the transcript of Illya Kuryakin's report, frowning. He removed his pipe from his mouth and, with the mouthpiece, tapped the description of Paul Rollins as if to sound a chest for a false bottom. His mind, like the memory bank of a great computer, was permitting a controlled cascade of associations and memories to fill his consciousness until he had recollected almost everything there was to know about Rollins.

Nevertheless it was wise to double-check, and of course to investigate the other suspects whose descriptions Illya had just given him. And besides, Waverly wanted to know the up-to-date whereabouts of the gaunt, scar-browed man.

He called Henderson in the Research Division of U.N.C.L.E. and immediately a review of the files was instigated on a Top Priority basis.

Rollins' file was dealt with first, and Waverly and his advisor sat before the screen of the information retriever, which scanned the organization's vast library of tapes for the one on which Rollins' data was located.

This data was printed out, while at the same time a photo of him was retrieved from the microfilm library and flashed on the Recordak screen, within moments after the instructions on Rollins had been programmed into the computer.

Waverly and Henderson studied the reports and renewed their acquaintance with the unpleasant features of Rollins. "Looks like an undertaker, doesn't he?" said Henderson.

Waverly nodded lugubriously. "That may be a more appropriate description than you think."

"Sir?"

"I believe he intends to bury us, you see. In molten lava." Waverly turned from the picture to the print-out of Rollins' dossier. "I know all this," he muttered impatiently, "but where is the data on his latest whereabouts?"

"Next page, sir."

Waverly flipped over the accordioned pages of the print-out and found, with considerable gratification, that as 1ittle as two weeks ago the U.N.C.L.E. agent in the Oklahoma sector had recognized Rollins and, with the help of state police, was having a routine surveillance placed on him.

"Please contact Reid in Oklahoma at once," Waverly said to Henderson, "and have him report fully on Rollins' precise location and activities."

Henderson, who recognized the imperative tone of Waverly's voice easily after years of working with him, rushed away from the retrieval computers as if fired out of a gun.

Waverly returned to his office and followed up on some other hunches he was coming to call "Dacian's volcano boxes." But he kept his eye cocked on his watch and wondered what was holding things up on that report from Oklahoma. Though an hour had gone by and no more, he still expected his organization to bring about a miraculous, instantaneous report.

As often as not, because he demanded miracles, he got them. But it took another two hours be fore Reid was on the communicator, spilling what he had learned about Rollins.

"He seems to be involved in an oil scheme of some sort, sir," Reid's husky voice told Waverly. "His procedures appear to be on the up-and-up; he purchased some land near here legitimately, and ditto for some tower scaffolding. The crew erecting the scaffolding don't smell too clean, however. A number of them have records or are otherwise suspicious."

"Very interesting," Waverly said, stuffing a wad of tobacco into a tan briar pipe and pushing papers around his desk in a hunt for his tobacco-tamping tool. "Have you or the police observed the presence of a box-like instrument with a large lens on it, like the zoom lens of a camera?"

"No, sir, but I do have one very interesting piece of information."

"Yes?"

"About ten days ago he cabled an innocuous message to Singapore. The cable address there was SINGOIL. Sounds like a contraction of Singapore Oil, which is probably the outfit behind Rollins' oil venture. That's all I know, sir."

![Книга [Magazine 1966-12] - The Goliath Affair автора John Jakes](http://itexts.net/files/books/110/oblozhka-knigi-magazine-1966-12-the-goliath-affair-232530.jpg)

![Книга [Magazine 1967-05] - The Synthetic Storm Affair автора I. G. Edmonds](http://itexts.net/files/books/110/oblozhka-knigi-magazine-1967-05-the-synthetic-storm-affair-180880.jpg)

![Книга Magazine 1967-07] - The Electronic Frankenstein Affair автора Robert Hart Davis](http://itexts.net/files/books/110/oblozhka-knigi-magazine-1967-07-the-electronic-frankenstein-affair-178273.jpg)

![Книга [Magazine 1967-12] - The Pillars of Salt Affair автора Bill Pronzini](http://itexts.net/files/books/110/oblozhka-knigi-magazine-1967-12-the-pillars-of-salt-affair-148925.jpg)

![Книга [Magazine 1966-06] - The Vanishing Act Affair автора Dennis Lynds](http://itexts.net/files/books/110/oblozhka-knigi-magazine-1966-06-the-vanishing-act-affair-117180.jpg)

![Книга [Magazine 1967-01] - The Light-Kill Affair автора Robert Hart Davis](http://itexts.net/files/books/110/oblozhka-knigi-magazine-1967-01-the-light-kill-affair-111851.jpg)

![Книга [Magazine 1966-09] - The Brainwash Affair автора Robert Hart Davis](http://itexts.net/files/books/110/oblozhka-knigi-magazine-1966-09-the-brainwash-affair-50701.jpg)

![Книга [Magazine 1967-10] - The Mind-Sweeper Affair автора Robert Hart Davis](http://itexts.net/files/books/110/oblozhka-knigi-magazine-1967-10-the-mind-sweeper-affair-42293.jpg)